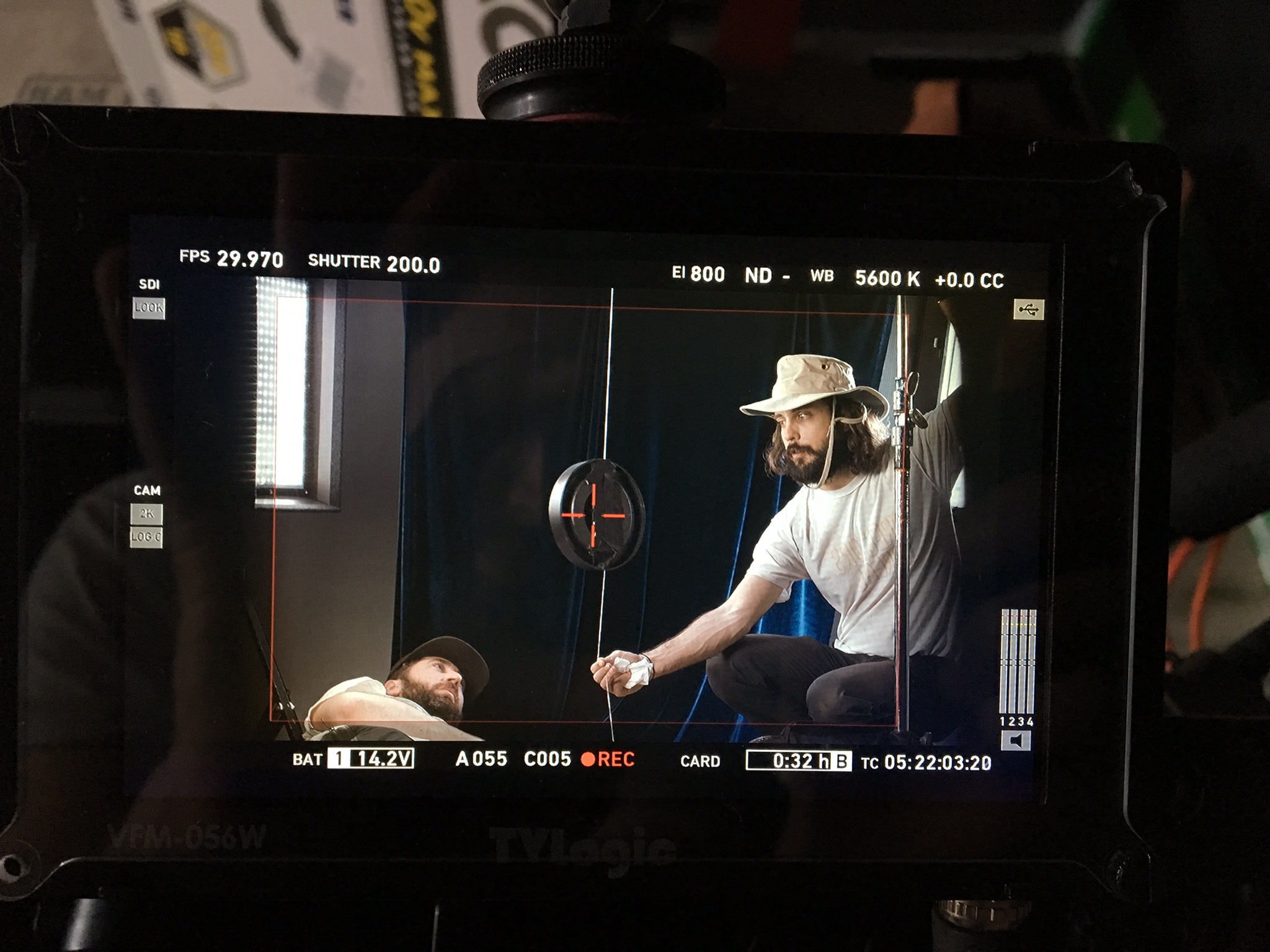

Sebastian Pardo (L) and Riel Roch-Decter (R) in the Memory office. Courtesy of Memory

Making a Production is Documentary’s strand of in-depth profiles featuring production companies that make critically-acclaimed nonfiction film and media in innovative ways. These pieces probe the creative decisions, financial structures, and talent development that sustain their work—in the process, revealing both infrastructural challenges and industry opportunities that exist for documentarians.

When Emily Mackenzie and Noah Collier premiered their debut documentary feature, Carpet Cowboys (2023), at Baltimore’s New/Next Film Festival, it was the result not of a dedicated film festival strategy but a longstanding web of personal connections. Carpet Cowboys begins as an early Errol Morris-esque film about the changing nature of the American dream as seen through the world of industrial carpet manufacturing in Dalton, Georgia, and ends up focusing on one peculiar Scottish businessman, Roderick James, whose personality inflects the film’s form.

Production was scrappy—one co-director held the boom and the other the camera—but the results are sleek. The film’s producer, Memory (sometimes stylized MEMORY), originally planned to bypass the festival circuit with Carpet Cowboys in favor of a DIY theatrical roadshow. Then the film’s publicist, Kaila Sarah Hier of Exile PR, informed the film team that former Maryland Film Festival director Eric Allen Hatch—and frequent selector of Memory’s projects—was putting on an alternative fest in Baltimore. That connection led to the film’s premiere. This spontaneity that is born from a foundation of longstanding relationships is a signature of Memory’s operation.

Like Carpet Cowboys, there’s a scrappiness behind Memory’s sleek exterior and dedicated cult following. The L.A.-based production company has only two full-time employees: its founders Sebastian Pardo and Riel Roch-Decter. The duo sought to create both a low-budget dream factory for passion projects and a sustainable network of filmmakers working in the DIY ethos of the 2000s, but with the stylistic inclinations of tidier, higher-budget productions. While they’re best known today for their boundary-pushing documentary projects—the essayistic films of Theo Anthony, Zia Anger’s cinematic performance My First Film (2018–2020), and Dean Fleischer-Camp’s narrativization of found footage in Fraud (2016)—Memory’s founders weren’t sure 10 years ago about the kind of product they’d be putting out, only the ethos behind it.

Early in Memory’s studio days, Pardo slapped a piece of paper on their office wall: “NO OSCARS! (NO SUNDANCE.)” Ten years in, their films now have premiered at the latter, a pragmatic upsetting of their more youthful aspirations. Yet when talking with Pardo and Roch-Decter, they still seem to have in mind an ethos built around working against the grain of outside validation and its attendant conventions. In a world of contracts, Memory is a company based on handshakes.

“Should we just do it, should we just start a company?”

In the same year A24 was launched, Pardo and Roch-Decter committed to starting their own production company, and by January 2014, Memory was official. They had met a few years earlier on the set of Mike Mills’s Beginners, with Pardo coming from the Directors Bureau, Roman Coppola’s stylish multimedia production company, and Roch-Decter working hands-on as an assistant for Olympus Pictures’ Leslie Urdang. By 2013, both had produced features—Gia Coppola’s debut Palo Alto (2013) for Pardo and M. Blash’s The Wait (2013) for Roch-Decter—and were starting to identify new stylistic trends in the independent space that weren’t being capitalized on by the existing modes of production.

Some of Memory’s first unconventional approaches would bear fruit, like Pardo contracting out his design skillset to make eye-catching, if minimal title sequences and posters for more better-financed independent features. While most of their output in 2014 was producing shorts, they also picked up Eva Michon’s music documentary Life After Death From Above 1979 (2014) as well as going into production on animator Carson Mell’s live-action feature Another Evil (2016). Over the next couple of years, they started to program shorts, playing their blocks at independent theaters like the Royal Theater in Toronto or Cinefamily in L.A., art spaces like PHI Center in Montreal, or even hotel venues like the Wythe in Brooklyn. These became the seeds of relationships that started to sprout.

Celia Rowlson-Hall, best known as a choreographer and dancer, had her 2013 short The Audition included on Memory’s first touring shorts program, and it was around this time that she approached Roch-Decter with a feature she had shot but needed help getting through post—Ma (2015), a modern reworking of the Virgin Mary’s journey, set in the American Southwest. It turned out to be the exact kind of personal, aesthetically confident film Memory had been looking for. Rowlson-Hall’s wandering yet destined road movie had naturalist landscapes that gave way to her impressionistic, interpretive-dance–influenced movement from the actors. The film was released by Factory 25 in the U.S., and being attached to this project led Memory to more fruitful collaborations.

While showing Ma at Rotterdam, they were approached by Theo Anthony, whose short doc, Peace in the Absence of War (2015), about the growing surveillance state in Baltimore in the wake of the 2015 uprising, was also screening. When Memory expressed interest in working with Anthony, he had two pitches for the company: (1) a straightforward documentary about “the strongest teenager in the world” who lived in Glen Burnie, Maryland, and (2) a film he couldn’t quite explain in a simple logline, something about rats, redlining, and the psychogeography of urban environments. It was that latter, more ineffable pitch that piqued Roch-Decter and Pardo’s interest, and they set about finding funding to complete Rat Film.

The finished film premiered at Locarno soon after Memory was named one of Filmmaker magazine’s “25 New Faces of Film” in 2016. Rat Film was not only a critical consensus favorite, but also recouped Memory and Anthony’s personal financial investment, paying back deferred fees through a combination of foreign sales, revenue from handling the film’s own theatrical release that generated US$35,000 in U.S. box office receipts, Cinema Guild’s downstream digital sales, and a US$90,000 broadcast license fee for Independent Lens (PBS). Notably, Memory’s DIY ethos was supplemented by traditional distribution paths, instead of relying on them.

It produced hopes for a growing and solvent future for Memory. They immediately got to work on Anthony’s next project, what would become an essay film on the power dynamics of images, All Light Everywhere (2021), as well as collaborating with ESPN on Subject to Review (2019), Anthony’s 30 for 30 episode on the instant replay systems in tennis and the nature of justice. There was still serious optimism when Subject to Review played on TV (Anthony likened it to a “coup”). But as Memory planned the release of All Light Everywhere as another massive milestone, their aspirations met their limit.

“This new model that was more direct-to-audience.”

“We did everything right,” Roch-Decter stated confidently, of how they set up the release of All Light Everywhere. Anthony’s second feature premiered at the biggest festival they thought they could get it to, the previously-off-limits Sundance, and got picked up by what they thought would be the biggest distributor that would consider it, Super LTD, an arm of Neon. But their hopes were quashed by the actual box office returns as one of the first films released in theaters after COVID lockdowns: US$37,000, which barely beat Rat Film’s performance despite costing a heftier (though still relatively cheap) US$450,000. The vast majority of its funding came from a handful of private investors and Sandbox Films. Pardo said that when they were starting out, they thought, If we could continue to make a certain level of film, market them in certain ways that are pleasing to us, put on events that would find an audience, then we would find a community of filmmakers that could one day be sustainable, and that there could kind of be this new model that was more direct-to-audience. What All Light Everywhere proved to Memory was that while working with a major distributor provided new opportunities, the lack of control over marketing and the film’s distribution strategy meant that neither the size of their audience nor its actual financial returns might scale with it.

Taking the lessons learned from All Light Everywhere and seeking a more Rat Film-like path, Memory took Carpet Cowboys on a road show. According to Roch-Decter, Carpet Cowboys was not only similar in budget to All Light Everywhere but also garnered similar box office returns through an entirely different release structure. Whereas All Light Everywhere had a conventional, if small, theatrical window through Super LTD, Memory distributed Carpet Cowboys themselves. They booked screenings with individual theaters and scheduled Q&As with the directors and the film’s executive producer John Wilson, trying to tap directly into local niche audiences from Albuquerque to Akron. This time, too, there was no expectation that Carpet Cowboys would be able to pay past the off-the-top expenses. It’s a characteristically Memory style of horizontal growth—they are confident in the films and willing to shift which roles the company plays, all the way from pre– to postproduction, in order to give the movies the best lives possible.

Memory is made up of businessmen: Roch-Decter rounded out his upbringing across Canada’s Laurentian Corridor by getting a degree in economics at Concordia, and Pardo has prided himself since his stint at Chapman for his ability to get projects in under budget and made as inexpensively as possible while still maintaining the highest levels of craft. When it comes to Memory, Pardo said that conventionally growing their company would have placed limits on the creative ability they sought for themselves and their artists: “I think growing would have meant being more compromised in terms of the level of artistic ambition, only because there almost seems to be a linear relationship to artistic ambition and money—and it’s not a positive linear correlation, it’s a negative linear correlation. The market just won’t yield things that I find rewarding and that’s the ultimate barrier to our ability to scale.” While A24 moves away from its independent roots, selling more and more “safe” products to subsidize smaller, riskier pieces, Memory keeps its branding tight by only taking on the projects they think will be creatively and artistically fulfilling. Even if their niche genuinely was too small to leave the company more solvent than subsidized, after the releases of All Light Everywhere and Carpet Cowboys, Memory is more secure in their ability to tap into latent artistic networks.

Memory’s broader community of collaborators is also showcased on their website under the “Releases” label (formerly “Presents”), which sometimes hosts virtual screenings or announces curated programs. Some of the programming is their own, such as highlighting two Robert Eggers shorts with their own pages; Hayley Garrigus’s exploration of the memetic internet underworld, You Can’t Kill Meme (2021); and Alex Tyson’s multilayered, experimental narrative concerned with crises in both image making and their afterlives, The Registry (2021). “People look to Memory to find work they would never encounter in normal streaming channels or normal screenings,” Tyson said. Having The Registry up on Memory’s site rather than just running the festival circuit or being a museum piece was a boon for audience engagement, especially with Memory’s releasing the soundtrack alongside it.

The most exceptional section of the “Releases” page is its masthead, “DEEP,” a series of “transmissions” curated by Chris Osborn from the recesses of online video. Osborn started the series in 2014 while doing content moderation for Vimeo, noticing a host of odd, surreal, and beautiful digital works by both clear craftspeople and apparent outsider artists. In 2016, Osborn approached Pardo and Roch-Decter at the Maryland Film Festival after a screening of Fraud. “They really saw a vision for [DEEP] to beam out on their website and through their connections at other festivals and other film organizations … across the United States and globally,” Osborn recounted. From 2016 to 2018, Osborn’s DEEP transmissions became a staple of Memory Presents, playing 24 hours a day for a month—the series selections and most recent transmission are meticulously archived.

Just before the pandemic, Memory was also exploring additional multimedia and expanded cinema possibilities. In the summer of 2018, Zia Anger pitched Roch-Decter a live cinema idea she had after being invited to present some of her “abandoned” works at Spectacle, a volunteer-run storefront microcinema in Brooklyn. In the My First Film (2019) performance, Anger types live notes from her laptop while showing excerpts from her DIY first feature, Always All Ways, Anne Marie (2012), which was rejected by every festival she sent it to. She knew Memory was “risky and excitable” because of their work with Anthony, her now-fiancé, and contacted Roch-Decter the same day after that presentation at Spectacle. This turned into a series of live performances at Metrograph, which was given a glowing writeup by Richard Brody in The New Yorker. Capitalizing on the momentum, and getting Cinema Guild onboard for further support, Memory put Anger on the road, doing performances at festivals, small theaters, performing arts centers, and universities. The harrowing, deeply personal, and intimate multimedia performance by Anger reflecting on the film industry’s unrealistic expectations and ethics attracted a dedicated audience.

“I’ve always had a really hard time identifying as a filmmaker,” Anger told me. “I was slightly Googleable, but it felt disingenuous to the fact that I wasn’t working 60 hours a week as a filmmaker, I was working 60 hours a week as a nanny.” My First Film was the first time Anger was able to support herself full-time through her artistic work, through its unconventional form and release model that had more in common, financially speaking, with being a touring musician rather than a director. Still, this did not translate into a self-sufficient career as a filmmaker. While redeveloping My First Film with Memory and MUBI into a fiction feature, she worked as a gardener in upstate New York with Anthony and their Australian shepherd, Holly. Since the release of All Light Everywhere, Anthony has been primarily working as a carpenter while slowly getting back into developing future film projects.

“We constantly reevaluate where we’re at. We’re not making the kind of money [other] people our age working [in the industry] are making,” Roch-Decter told me.

“We just have to take a lot of time.”

After Carpet Cowboys wrapped its roadshow in early December 2023, I sat in on a post-mortem call with Roch-Decter and Carpet Cowboys co-directors Mackenzie and Collier as they rounded up the successes and tribulations of their roadshow, started work to close up the accounts, and talked about the possibilities of the film’s afterlife (VOD, streaming, Blu-rays) to best keep connecting with the audience. The film’s funder, XTR, also came up. XTR’s streaming service and FAST channel Documentary+ was discussed as an expected landing place if another streamer didn’t pick it up. A week after this conversation, Filmmaker released a critical piece on XTR, in which Roch-Decter was quoted diplomatically saying he had “a great experience” working with XTR amidst a sea of claims by filmmakers claiming they were basically hoodwinked into thinking the company was going to help them get funding.

While Memory has a host of successful, long-running collaborations, as with other production companies, not everything has worked out. For instance, according to Roch-Decter, Memory worked with Leilah Weinraub in the post-production process on Shakedown (2018), a documentary shot by Weinraub primarily over the eight-year run in “a utopic moment” of the titular Black lesbian strip club in ’90s Los Angeles. “[Memory] came in the edit and helped the director Leilah Weinraub complete the film ahead of its world premiere in Berlinale and U.S. premiere at True/False. Beyond post and the first few premieres, Leilah wanted to handle the sale and distribution of the film on her own,” Roch-Decter explained. Weinraub would go on to partner with Grasshopper to release the film on Criterion Channel and PornHub simultaneously, including a live chat element on the latter’s platform.

Relationships relying on handshakes, be they financial or personal, are always going to be delicate. But Memory is not alone in this camp, as much of the documentary world moves at the speed of trust, pointing to a larger problem in the ad hoc organizing of the wider world of nonfiction filmmaking. What is unique to Memory is how they have made a name for themselves by overdelivering on the presentational quality of their films compared to their low budgets. However, Pardo and Roch-Decter claim this quality has created inflated expectations of their existing financial resources; because their films look polished, potential funders and colleagues assume that they don’t need money.

Their actual solution strikes a contradiction within the utopian aspirations of Memory to build a space where filmmakers can pursue passion projects. “We don’t have a lot of money, so we just have to take a lot of time with the films,” Roch-Decter said. This leads to long production processes filled with constant revision by the filmmakers that has tended toward a redundant self-reflexivity, which Memory readily acknowledges.

“You spend the film being like, ‘This is a construction, I’m in control of this.’ How many times do you want to do that? Eventually, you just go make a fiction film,” Roch-Decter joked. While their statements about reaching the end of documentary form are hyperbolic, they belie a desire to break from their currently established brand. Pardo and Roch-Decter told me they’ve had people approach them about wanting to make their own “Theo Anthony film.” But they’re not looking for another Theo Anthony—they’re looking for something new.

Alex Lei is a writer and filmmaker based in Baltimore.