-

Amir Aziz, Director

-

Michael Niederman, Director

-

Dan Norland, Producer

About the Project

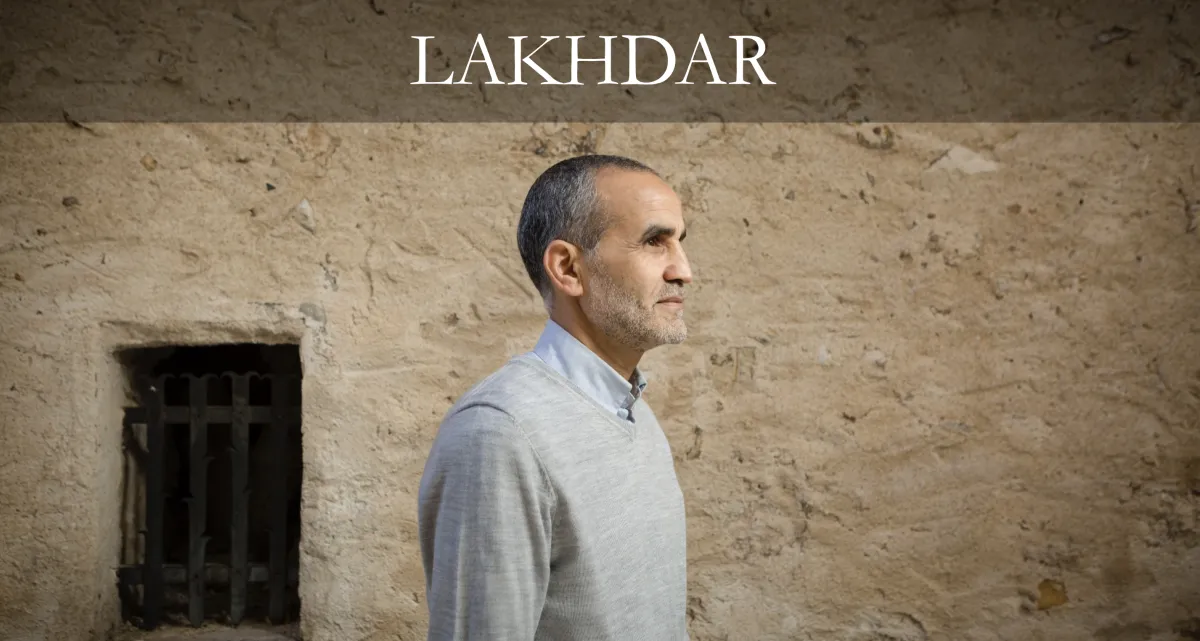

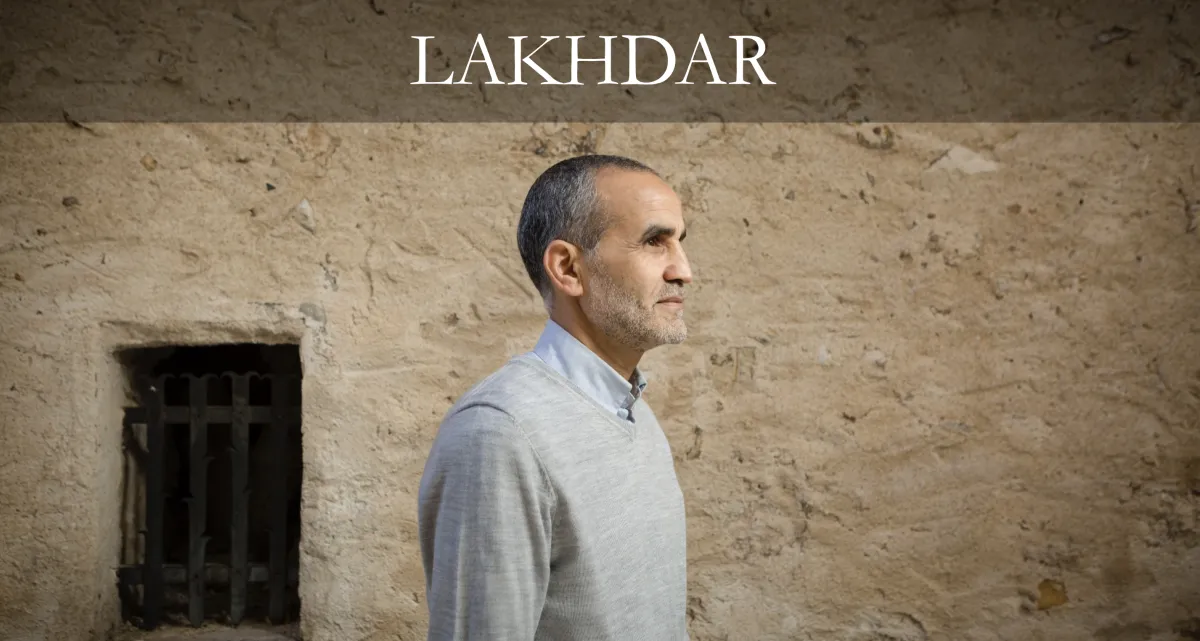

Image courtesy of Rebecca Marshall Photography at rebecca-marshall.com.

Kidnapped and taken to Guantánamo Bay by the US military, Lakhdar Boumediène was wrongfully detained and tortured at the notorious prison for seven long years. Now a free man leading a quiet life in Nice, France, Lakhdar embarks on a journey to seek answers and some measure of justice for Guantánamo survivors.

An Algerian citizen, Lakhdar was a charitable aid worker for the Bosnian Red Crescent Society in 2001, living a peaceful life in Sarajevo with his wife and their two young daughters. In October of that year, he was wrongfully accused, along with five other Algerians, of plotting a terror attack against the US embassy in Sarajevo. To this day, he has no idea why anyone ever suspected him of this.

Kidnapped, shackled, and renditioned to Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp in Cuba, Lakhdar was detained there from January 2002 to May 2009, with no charges ever filed against him. He endured brutal beatings, interrogation sessions, and uncertainty about whether he would ever see or even speak with his family again. Steadfast in his innocence, he embarked on prolonged hunger strikes to protest his mistreatment and was subjected to painful force-feeding sessions, strapped into a ‘torture chair’ specifically built for that purpose.

In 2008, Lakhdar accomplished an extraordinary feat. Having never lost faith that he would one day establish his innocence and win his freedom, he prevailed in a landmark US Supreme Court case that bore his name, Boumediène v. Bush, which held that Guantánamo detainees have a constitutional right to challenge their detention in federal court. He then appeared before a George W. Bush–appointed federal judge, Richard J. Leon, who reviewed the government’s case and ultimately found that it had none.

It had taken the better part of seven years – and extraordinary courage and perseverance – for Lakhdar to get his day in court. But once he did, it took just a few weeks for it to become clear that he never should have been detained in the first place.

In May 2009, Lakhdar was finally reunited with his wife and daughters in France, where they were to be resettled. Their tearful reunion in Paris, though joyous, was also marked by his sorrow at having missed seven precious years of his two young daughters’ lives.

The name Boumediène has since become synonymous with the principles of justice and due process: Boumediène v. Bush marked a historic legal milestone enshrining the right of non-US citizens to be protected from unlawful and indefinite detention. Where Korematsu has become a shorthand for the United States’ willingness to abandon the Constitution in wartime, Boumediène represents a refusal to do so, albeit one that came far too late.

Lakhdar now lives with his wife and three younger children, resuming their lives in a quiet village perched along the French Riviera, a short drive from his two older children and his grandchildren.

Lakhdar has managed to rebuild a life for his family and himself, despite everything they went through. But he still bears scars, physical and emotional, from his years at Guantánamo. He still wonders how the US government could have ever thought he was a terrorist and whether they would ever offer him an explanation or any measure of justice for what he went through.

Our documentary film, LAKHDAR, is birthed from Lakhdar Boumediène’s powerful will to tell his incredible story of survival to the world and his desire to stop it from happening to others in the future. As the man who won a landmark Supreme Court case against a sitting US president, Lakhdar knows the immense historical weight his name carries - or should.

The film steps into Lakhdar’s world: We follow him in present-day Nice as he rebuilds his life, navigates France’s culture and customs, and experiences fatherhood for the second time. We listen to him and his family share the story of what they went through. We follow him as he seeks an official apology and some measure of justice from the US government.

As the most enduring manifestation of the US ‘War on Terror,’ Guantánamo conjures paradoxical sensibilities in collective memory: shock and outrage at its extreme practices, on one hand, and a stubborn conviction that Guantánamo had actually housed “the worst of the worst,” on the other. There is an almost amnesiac forgetting of the depth of public and political complicity in justifying Guantánamo’s cruel practices. Many Americans regard Guantánamo as a closed chapter in history, despite its continued existence, and many members of younger generations do not even recognize the word ‘Guantánamo.’

Recognizing that Guantánamo continues to cast a dark shadow over the many lives it has affected, LAKHDAR addresses two important questions. First, what happens to people who experience Guantánamo? How can anyone survive it, or how does one ever adjust to ‘normal’ life after witnessing its horrors? Second, will the US government do anything to try to right the wrongs of Guantánamo? Have our legal and cultural understandings of torture and detention changed in any meaningful way? Have we learned anything from Boumediène, the case, or from Boumediene, the man?

The film’s stakes are no less than combatting the dehumanization that makes atrocities like Guantánamo possible. As we follow Lakhdar in his life post-Guantánamo and witness his joys and his struggles, we will examine challenging and important issues ranging from the immense physical and psychological effects of torture and the consequences of Islamophobia after 9/11 to whether men like Lakhdar could ever hope for redress – or even just an apology – from those responsible for their ordeal.

LAKHDAR reminds us that we must not look away from the horrors of Guantánamo or from the humanity of the men tortured there. It is an urgent reminder of the heavy debt the US still owes people like Lakhdar and their families.