Embrace Friction: Highlights from ‘Embodied Infrastructure: Disabled Immersive Nonfiction’

Largely due to the ongoing efforts of disabled artists and activists, ensuring art is accessible—to both audience members and artists—has moved from the margins to a central topic in creating, producing, and staging immersive nonfiction. We’ve seen the conversation reach major stages through initiatives like the 2022 Film Festival Accessibility Scorecard, a step toward institutionalized accountability and rewritten best practices for showcasing accessible art. From including CART and ASL transcriptions in live events (like this one) to including content warnings in depictions of triggering content, meeting access needs is a start in the larger conversation around supporting and centering disabled voices in nonfiction storytelling.

On June 29, 2023, IDA’s Nonfiction Access Initiative (NAI) convened artists and industry leaders to discuss best practices that both creative practitioners and industry experts can take to center access and disability justice in their work. Opening with artist talks from M Eifler, disabled immersive artist and director of BlinkPopShift, a disability futures lab, and Nat Decker, disabled mixed-media sculptor and access worker, the panel also featured:

- Joanna Wright from the Access and Disability Working Group at MIT Open Documentary Lab’s Co-Creation Studio, a studio devoted to collective creation with community and the exploration of new documentary forms

- Vanessa Chang from Leonardo, the International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology, a research platform that has convened disabled creatives and scholars in its 2022 CripTech Incubator and 2023 Metaverse Lab, two opportunities to write about and display artwork at the intersections of technology and disability innovation

- Sultan Sharrief from the Quasar Lab, a multidisciplinary laboratory in incubation at USC’s Media Arts and Practice program that develops long-term solutions for social change across film, music, big data, immersive technology, and critical pedagogy

The virtual event, titled “Embodied Infrastructure: Disabled Immersive Nonfiction,” highlighted both the expansive possibilities of and the work needed for centering disabled voices in immersive storytelling. Moderated by Cielo Saucedo, NAI Funds Program and Access Coordinator, the panel touched upon the following three key themes:

- Accessibility is a lens that can (and should) be integrated throughout the process of curation, creation, and consumption. Several panelists proposed key frameworks for understanding when accessibility plays a role in the creation and consumption of immersive art. These include M Eifler’s “Who Body and When Body,” which takes into account whose body is involved in the making and experiencing of the artwork, and Sultan Sharrief’s frameworks that prioritize genuine iteration, listening to gut instinct, and the cripping of time in the process of building out an art project.

- Centering disabled voices in content creation and the tangled intersections between audience and artist in immersive art allows for generative, imaginative possibilities for disabled embodiment and storytelling—dreamily penned by panelist Nat Decker in their own art practice in “crip fantasy.” Artists like Decker demonstrate the creative ingenuity disabled folks have been forced to develop in situations of restriction. That said, when given the opportunity to build their own tools and describe their body-mind realities on their own terms, disabled folks can dream up infinite possibilities and futures.

- These efforts to prioritize accessibility take ongoing work, a willingness to try and fail, and a wholehearted embracing of “friction” when access needs are not being met. In a world where the status quo is ableist, deprioritizing voices that may not even be at the table, it is about the ways in which folks respond to those moments of “friction” that are the most important. Panelists, particularly in the roundtable discussion after the artist talks, offered tips from their own experiences around (re)constructing more inclusive workflows, dealing with issues of autonomy and consent, and building longer-term infrastructure through training and compensation to get more disabled folks at the table.

This piece summarizes the key points, and quotes have been edited for length. For the full event recording, click on this link.

Accessibility is a lens that can (and should) be integrated throughout the process of curation, creation, and consumption.

M Eifler, who wields over a decade of experience building immersive tech, opened the session with a framework of how embodiment plays a role in the methodology behind an immersive project. Understanding “who” and “when” can establish a baseline for the types of emotional implications immersive art will have. When engaging with a project, it’s important to notice who’s participating in the embodied experience, and whose body is engaged: is it the artist, the viewer, or both in some form? It’s also important to understand the point in the process where embodiment was integrated into the creative experience. Eifler cited a lot of work being completed on screens and flowing to a multiplicity of interaction points like mobility and sensory devices. Using frameworks like these, artists can achieve fuller, richer immersion based on a clear definition of the environment and the digital and analog tools used, from using body work to heighten the impact before a headset comes on to clearly setting the stage with expectations before an experience begins.

When probed for what they define as an “immersive” work, panelists pushed for a more expansive view beyond the traditional expectations of putting on a headset and watching something in VR. Said Sultan Sharrief, “Virtual reality is where I do a lot of work, but ‘immersive’ is any space that shifts presence, with sound, smell, visual, tone/context. ‘Safe spaces’ can be immersive environments.”

For Sharrief, building “immersive” experiences with care starts early. To do access work justice, Sharrief emphasized the importance of holistically examining your own positionality, limitations, and who you’re convening as collaborators. In sharing his own creative timelines as a filmmaker and mixed-media artist, Sharrief emphasized how much space he makes for slowness and “crip time”—that is, deadlines exist to be pushed, and iterative spaces need to actually give time for iteration versus falling into a hyper-capitalistic “status quo.”

Centering disabled voices in content creation and the tangled intersections between audience and artist in immersive art allows for generative, imaginative possibilities for disabled embodiment and storytelling.

Both M Eifler and Nat Decker’s artist showcases were a glimpse into the queer, trans, and disabled possibilities of immersive art.

Eifler presented one project in which they literally embrace what could be their nude virtual body, stylized and changed by top surgery—the healing of which they see as incompatible with their disability—in Bodies of Meat and Light (2017–18). The viewer “crawls” into bed with this body, experiencing an intimate, first-person “mirroring” of Eifler’s own interactions.

The other project presented, Masking Machine (2018), was a wearable AR apparatus that functioned as a “prosthetic of simulated eye contact” for Eifler, an autistic person who struggles with eye contact, to make an otherwise challenging social expectation more manageable. The wearer was portrayed to others in a room behind a screen in a stylized form, collapsing the experience of interacting with someone in physical space with a simulated self, similar to the way someone might interact with an Instagram filtered selfie: beautified, enlivened, et cetera.

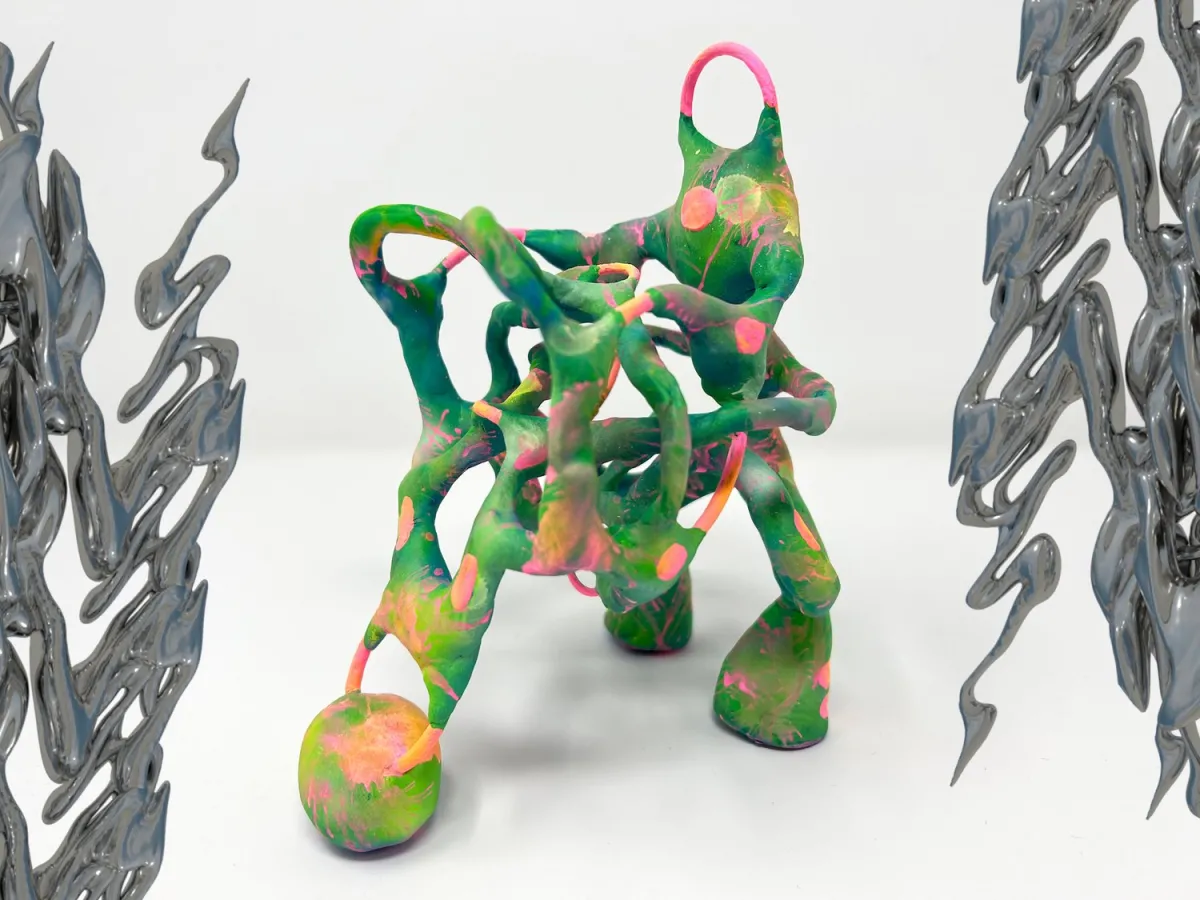

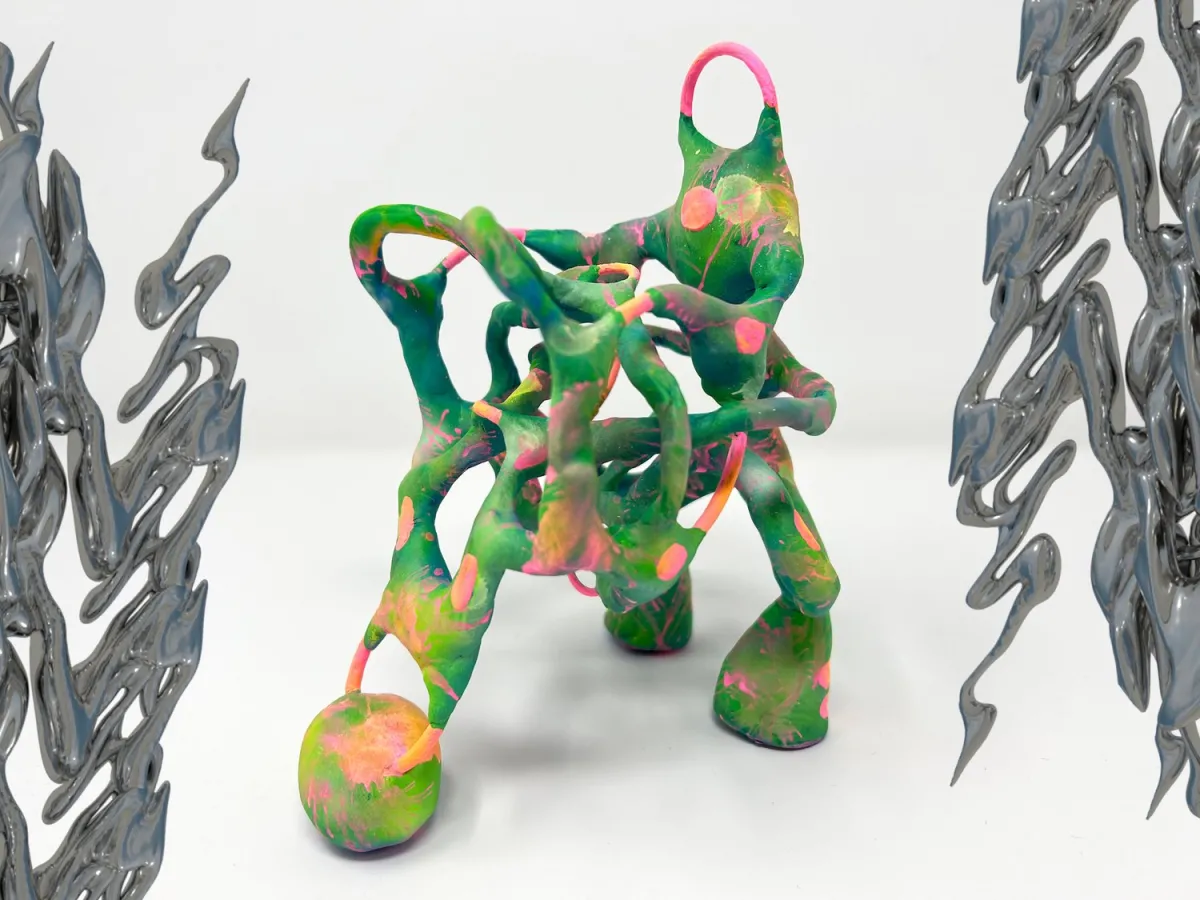

Nat Decker’s work, which lives predominantly on their Instagram, focuses on mobility devices as a site of crip narrative, “reimagining the wheelchairs, walkers, scooters, canes [they] use each day with vivid, celebratory color and agitations of conventional desirability politics.” These sculptures, which come in countless variations of neon colors and serpentine forms that are simultaneously haunting and cute, stretch across and between the digital and physical. Decker’s work pushes audiences to think of mobility devices beyond their prescribed sterility—boring, hyper-utilitarian shades of grey—and in doing so fantasize beyond the “unidimensional prescriptions of what the disabled body is and what it can do.”

Decker also examined what these possibilities look like when “disability hacking”—the ways disabled folks have and continue to make and break technologies to explore creative forms of self-expression (often working through access restrictions) to write themselves into existence using systems in place. They shared an image of a 3D Memoji of themselves, built with Apple’s avatar-builder, which depicts a friend pushing them in a wheelchair. Decker describes this as the closest thing to representation of a wheelchair user they could find. While tongue-in-cheek, these reimaginations are a balancing act of pointing out the narrow definitions of disability these assets portray while also providing a radical reclamation of what could be.

This praxis flows into much of their academic and community-organizing work as well. Decker emphasized bringing in the extraordinary generosity of their communities’ time and skills, while also paying it forward in skill-sharing, just compensation for time, and the seeding of sustainable infrastructure to continue prioritizing disabled voices and access in the arts.

These efforts to prioritize accessibility take ongoing work, a willingness to try and fail, and a wholehearted embracing of “friction” when access needs are not being met.

While it can be daunting to imagine all the places that need more work, panelists offered a few starting points for strengthening the current infrastructure for disability storytelling, as well as leaning into the moments of “friction.” With infinite possibilities for how someone might engage with a work, and how their access needs might or might not be met at the point of contact, how do creative practitioners and curators embrace the tension and build new solutions together?

“It takes humility to get things wrong,” answered Joanna Wright.

Vanessa Chang stressed the importance of ensuring disabled representation in the beginning—it is more costly and less effective to have access be integrated only as a Band-aid solution at the end. At a baseline, there needs to be shared language and education so that everyone can understand and respect each other and contribute.

M Eifler chuckled and said, “I do it to myself a lot and see if it sucks.” Eifler spoke about seeking firsthand experience with daily spherical recordings for a year to understand the impact the request might have before asking it of others. It’s about asking the right questions to give people the information to make an informed, consensual decision to participate

This also brought up the question about consent, especially in the data-rich world we live in. With the rise of generative AI tools, this issue has become a recent hot topic, and panelists spoke about the challenges in seeking consent for generated images portraying disability, as well as ensuring self-autonomy in their own representation of disabled folks when these tools are not in their hands. As these technologies develop, it is important to continue conversations around ethical representation and also acknowledge the trade-offs of a “build fast, break things” technological model that perpetuates a status quo that too often leaves out disabled folks.

Panelists also found consensus around the importance of skill-sharing, looking for spaces—both institutional and grassroots—to embed long-standing educational initiatives and build community. Part of this process is bridging material support, and part of it is looking for allies and conspirators invested in putting in the work.

For more information about NAI and its attempts to build critical infrastructure by inviting disabled immersive makers to fill out the Nonfiction Media Makers with Disabilities Survey, please click here.

Julie Fukunaga (they/them) is an occasional writer, neurodivergent spoonie, and queer digital media enthusiast based in the Bay Area. They most recently edited at MIT Immerse, a publication centering immersive documentary that most recently published an issue about disability justice, access, and storytelling.