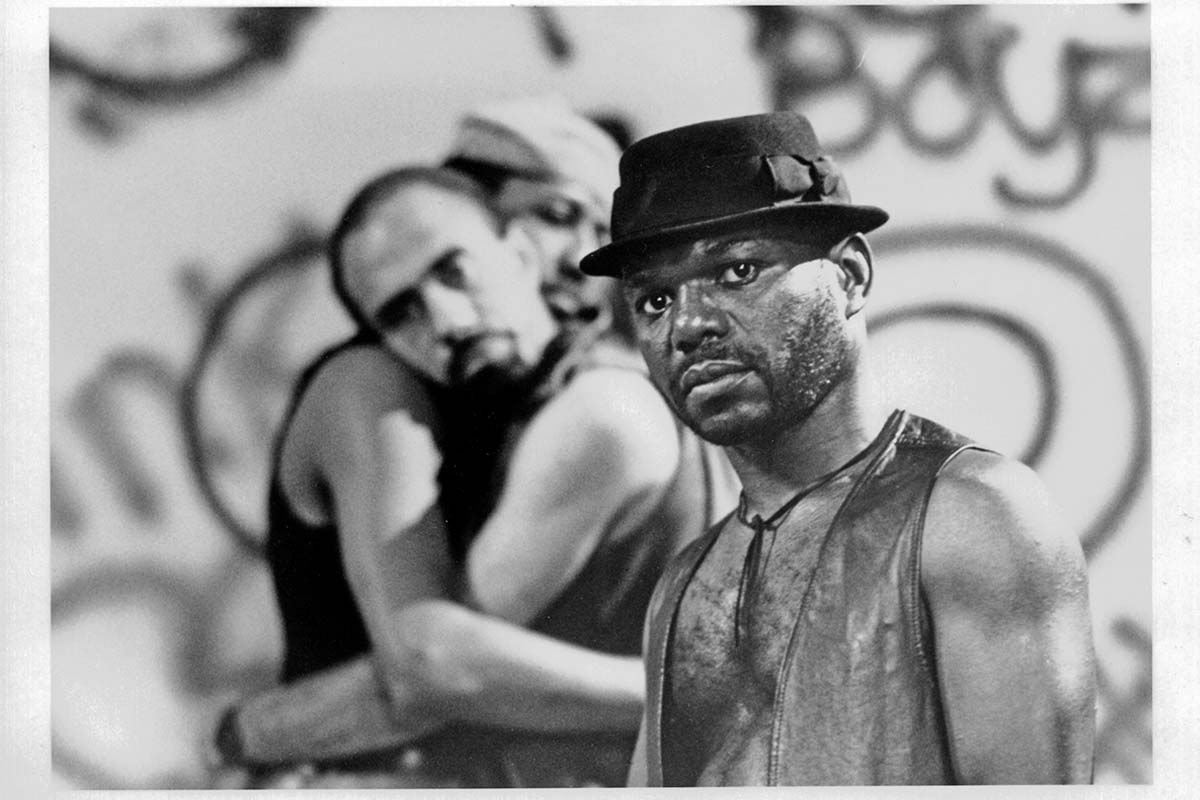

In 1991, Marlon Riggs made history with the POV premiere on PBS of his groundbreaking film Tongues Untied. It was at the height of the culture wars as well as the AIDS pandemic, and Tongues Untied intersected both crises. It became a lightning rod for conservatives who were looking to maintain the old-world order; they denounced the film on the floor of the US Senate. It also became a beacon and a call for action for those communities and voices marginalized and stigmatized by the status quo of white supremacy and homophobia.

In 1991, Marlon Riggs made history with the POV premiere on PBS of his groundbreaking film Tongues Untied. It was at the height of the culture wars as well as the AIDS pandemic, and Tongues Untied intersected both crises. It became a lightning rod for conservatives who were looking to maintain the old-world order; they denounced the film on the floor of the US Senate. It also became a beacon and a call for action for those communities and voices marginalized and stigmatized by the status quo of white supremacy and homophobia.

In this personal and performative documentary, Riggs comes out not only as a Black queer man but also as HIV-positive and battling with the disease. The film is a manifesto that calls for Black gay men to unburden themselves of the shame-induced silence and claim the centrality and dignity of their identity and voice. This at a time when it was almost unimaginable that Pose, RuPaul’s Drag Race or Master of None would be dominating the broadcast and streaming platforms.

Riggs’ work set a stake in the ground in documentary filmmaking. His more experimental work was unapologetically produced out of, and for, a Black queer communal perspective. Because it maintains this integrity, the work was authentic, universal and groundbreaking. It was also prescient, given the current refocusing of documentary to make transparent the nuances of the relationship between makers and the communities depicted within their films—now central questions for funders and commissioners of documentary from Sundance to Ford to ITVS.

Riggs’ more formally experimental work would not have been possible had he not produced other documentaries that, while more conventional, broke new ground around examining pervasive power of enduring Black stereotypes in shaping American popular culture. These films—Ethnic Notions and Color Adjustment—explore the shame and disenfranchisement these images engendered. Even as they afforded A-list Black artists with opportunities and mainstream success, they served to malign, denigrate and exploit African Americans as sub-human.

These two pillars of Riggs’ work—the more personal/artistic and the journalistic—are rarely discussed, screened or examined together in a way that allows us to see the full impact of his compact but dense oeuvre, as well as his own relationship to these multilayered films.

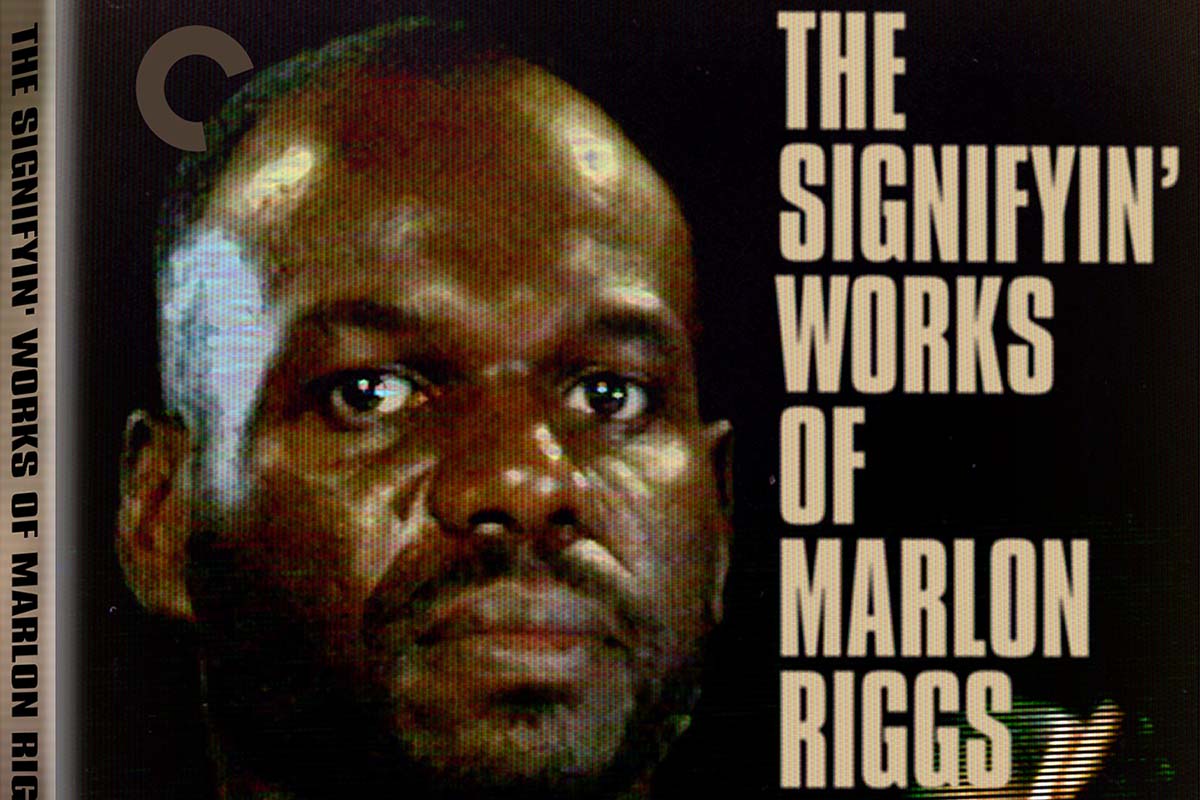

But now there is a way to experience Riggs’ full body of work with the recently released Criterion Collection DVD set, The Signifyin’ Works of Marlon Riggs, which includes all seven of his films in new high-definition digital masters, with uncompressed monaural or stereo soundtracks. Released as part of Criterion’s continuing series of important classic and contemporary films, this collection traces Riggs’ evolution as a transformative filmmaker tackling the devastating legacies of racist stereotypes, the impact of AIDS on his community, and the very definition of what it means to be Black in a post-colonial world.

But now there is a way to experience Riggs’ full body of work with the recently released Criterion Collection DVD set, The Signifyin’ Works of Marlon Riggs, which includes all seven of his films in new high-definition digital masters, with uncompressed monaural or stereo soundtracks. Released as part of Criterion’s continuing series of important classic and contemporary films, this collection traces Riggs’ evolution as a transformative filmmaker tackling the devastating legacies of racist stereotypes, the impact of AIDS on his community, and the very definition of what it means to be Black in a post-colonial world.

The collection allowed me to screen Riggs’ UC Berkeley graduate thesis film, Long Train Running: The Story of Oakland Blues (1981), for the first time. Although a formally traditional doc, you can see his commitment to showing the beauty and power of this community of blues musicians, while also not shying away from the tragedy of poverty, exploitation, and the ongoing trauma of racial oppression. While Black photographers such as Lewis Watts, in his book Harlem of the West, have explored and documented the westward Black migration, Long Train Running may be the first documentary to depict it cinematically and through the music. In the various DVD extras, we come to understand that Riggs’ personal story parallels that movement from the South (Texas) to the Bay Area.

The DVD booklet design captures the poetic flair that infuses Riggs’ work. It juxtaposes the descriptions and credits for the films with Riggs’ most iconic imagery. The centerpiece essay, by film critic K. Austin Collins, incisively contextualizes Riggs’ body of work:

If his films teach us anything…it is that Riggs’ life and canon are hardly reducible to any one facet. He loved hard—within his work, in the way he made that work, and on behalf of that work. Which is also to say that he fought hard: in the very forms of the films he made, the gaze and substance and sinews of them, and for the people he made them about and for, the audiences whom he could impel out of silence and into truer notions of themselves.

Full disclosure: I knew Marlon Riggs—the person, the work and the legacy. I was fortunate to meet and befriend him in 1989 as he was working on Tongues Untied. During one of his trips to New York, the poet Colin Robinson brought him over to my house for a visit. We quickly became friends, dialoguing around the new Black Queer renaissance we were experiencing, with cultural output across the country as well as in the UK with Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston, which had come out just a few years prior.

Full disclosure: I knew Marlon Riggs—the person, the work and the legacy. I was fortunate to meet and befriend him in 1989 as he was working on Tongues Untied. During one of his trips to New York, the poet Colin Robinson brought him over to my house for a visit. We quickly became friends, dialoguing around the new Black Queer renaissance we were experiencing, with cultural output across the country as well as in the UK with Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston, which had come out just a few years prior.

Besides being a friend, Marlon was a mentor and I never missed an opportunity to see him deliver a keynote and participate on panels at the many conferences on media and cultural studies, including the 1991 Black Culture Conference. I, like many others, credit Marlon with providing me with the courage and tools to officially come out at PBS affiliate WNET as queer, as well as leave the corporate trajectory as a staff producer to pursue my artistic work in media. Later Marlon would hire me to film some of his 1991 short, Anthem, also included in the DVD along with his other experimental shorts Je Ne Regret Rein and Affirmations—works that, like Tongues Untied, feature Black queer communities with whom Marlon deeply collaborated and whom he considered his primary audiences. Like him, they are featured in front of his lens, dancing, performing, reading and emoting—engaging in co-creation as a liberatory force and practice.

A quarter-century after his death, Marlon has inspired an increasing and renewed interest in his work, with retrospectives at BAM, the Pacific Archive and David Zwirner Gallery, as well as internationally at the Massimadi Brussels LGBTQ Film Festival of Africa, the Diaspora in Belgium and the Encountro do Cinema Negro Zozimo Bulbul in Rio De Janiero. Younger generations, BIPOC and queer, are discovering Marlon Riggs while looking for a lineage and a message so resonant with their lives. That his work is motivating new audiences is phenomenal, given that no book or definitive study about his work exists.

In this regard, The Criterion Collection, chock full as it is with extras, really helps to flesh out Marlon’s process, his vision and his life. It includes four new programs featuring filmmaker and editor Christine Badgledy, performers Brian Freeman, Reginald T. Jackson and Bill T. Jones; film and media scholar Racquel Gates; and sociologist Herman Gray. These are Riggs’ collaborators, friends and inheritors. A central theme in this astutely curated collection is the connection across communities touched by Marlon in disparate ways. This is evidenced in the 2020 discussion between Criterion Programmer Ashley Clark (who also programmed the BAM retrospective) and filmmakers Vivian Kleiman and Shikeith. Kleiman, a veteran Bay Area filmmaker who was a neighbor of Riggs and later a collaborator and dear friend, provides an oral history of his evolution from student to editor to filmmaker to professor at University of California, Berkeley, while taking us through a tour of his films. "Marlon valued his teaching over his own personal film productions," she recalls. "He was dedicated to motivating students to unpacking, deconstructing their lives, their stories. Marlon felt that if you’re good at what you do in your creative work, it is your responsibility to pass it on to the next generation."

Shikeith, a young queer media artist, describes how he came across Marlon’s work and what it meant to him: "I was searching Tumblr and putting in hashtags and along the way I found Tongues Untied and so I’m, 'Oh shit, like someone beat me to the punch. '… Discovering Marlon affirmed this history, that I didn’t exist in a vacuum, that there was this legacy of Black queer men before me who had been doing this work to help us reconcile all these psychic wounds that we have been impacted by and continue to be impacted by."

This conversation in some ways updates a 1996 documentary about Marlon Riggs entitled I Shall Not Be Removed, by his former student Karen Everett. Made with Riggs’ full cooperation and completed two years after his death, the film is a compelling memorial of his life and work, and the way the two intersected. Drawing from extensive outtakes of his films, behind-the-scenes footage, his teaching, public talks and introductions at film festivals, the doc shows Marlon Riggs in action, and his presence is palpable, whether in the full intensity of his work, or on hospital beds as he battled for his life.

I Shall Not Be Removed, like the other DVD extras, takes us into Riggs’ communities—professional, creative, familial, amorous—from which he drew nurturance, and that enveloped and supported his vision and his life. His mother and grandmother are frequent commentators; they discuss the impact of Tongues Untied on them and their relationship with Marlon over time. The film candidly portrays the story of Marlon and his partner, Jack Vincent, who, like Marlon’s film production family, is steadfast by his side until the end. We see Riggs working with the production teams, some of whom would go on to finish his final work, Black Is… Black Ain’t, posthumously. I Shall Not Be Removed invokes for me another documentary, Silverlake Life: The View from Here, by Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman, also about a gay couple navigating love, AIDS, death and the filmmaking process. I Shall Not Be Removed provides a depiction of art and life that feels rare in the pantheon of gay and Black stories. It also feels timely in this pandemic era, where family members are often deprived of even an opportunity to say goodbye to a loved one.

I Shall Not Be Removed, like the other DVD extras, takes us into Riggs’ communities—professional, creative, familial, amorous—from which he drew nurturance, and that enveloped and supported his vision and his life. His mother and grandmother are frequent commentators; they discuss the impact of Tongues Untied on them and their relationship with Marlon over time. The film candidly portrays the story of Marlon and his partner, Jack Vincent, who, like Marlon’s film production family, is steadfast by his side until the end. We see Riggs working with the production teams, some of whom would go on to finish his final work, Black Is… Black Ain’t, posthumously. I Shall Not Be Removed invokes for me another documentary, Silverlake Life: The View from Here, by Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman, also about a gay couple navigating love, AIDS, death and the filmmaking process. I Shall Not Be Removed provides a depiction of art and life that feels rare in the pantheon of gay and Black stories. It also feels timely in this pandemic era, where family members are often deprived of even an opportunity to say goodbye to a loved one.

As filmmakers Cheryl Dunye and Rodney Evans and poet Jericho Brown testify in one of the moving short films that are part of the collection, one cannot overemphasize the impact that Riggs’ form of storytelling had at the time, and continues to have. For me, Marlon’s work and his generosity of spirit helped shape my own practice as a socially engaged artist working in media. His innovation in form—bold, queer, emotive—opened up space to be authentically myself regardless of boundaries of discipline. Bringing communities into conversation, interrogating Black families through queer eyes, and critiquing new manifestations of the stereotype at play in popular culture, are things that continue to resonate with my own work, and in this way, Marlon Riggs is very much alive for me. As he says in I Shall Not Be Removed, "There is a living spirit within me that which wants to connect with other people and pass on something to them that they can use in their own lives and grow from."

Thomas Allen Harris is an award-winning filmmaker and artist whose work across film, video, photography, and performance illuminates the human condition and the search for identity, family, and spirituality. His deeply personal award-winning films have received critical acclaim across the landscape of international television, art and film festivals. Harris is Senior Lecturer at Yale University, jointly appointed in African American Studies and Film & Media Studies.