Debuting March 30 on HBO is veteran writer-director (30-plus films over the last four decades) Jay Rosenblatt’s 2021 Sundance-premiering, Oscar-nominated When We Were Bullies. Inspired by a stranger-than-fiction coincidence from 25 years ago, it’s an astonishingly personal journey (a "spiritual quest") back in time to a schoolyard bullying incident that the filmmaker participated in, a half-century past. It’s also one wildly creative documentary short, packing contemporary phone interviews with classmates (and a now-nonagenarian teacher); archival material, found footage, and even whimsical stop-motion animation into its brisk 30-some-odd-minute running time.

But perhaps most surprising—and laudable—of all is how much Rosenblatt chooses to reveal about himself. Which is why Documentary is delighted that the Brooklyn-born, San Francisco-based director—a Guggenheim and Rockefeller fellow who also holds a Master's Degree in Counseling Psychology and once worked as a therapist—agreed to be our March Doc Star of the Month.

DOCUMENTARY: Though you’re no stranger to personal projects, When We Were Bullies strikes me as especially raw and vulnerable filmmaking. Why was it important for you to place yourself so prominently in this film—to own your complicity onscreen in a way that exposes so much of yourself? I could see a version in which you might have shifted the focus away, say, by letting Richard J. Silberg take the lead.

JAY ROSENBLATT: Well, I have to say it kind of evolved. I’ll give you a good example—I never intended to bring my brother’s death into this film. It wasn’t even on my mind. I made a film about that called Phantom Limb. It’s not all about that, but his death is a point of departure for that film to take off and be about grief and loss.

So I didn’t think I’d do that again—in a different way, of course—but it evolved organically. A lot of people that I interviewed, when I’d ask them what do you remember about me from that time, many of them—actually it was all women, I think—said, "Well, I remember something that was very difficult for you." And they talked about my brother’s death. I just couldn’t believe it—I was so shut down then and I really kept it hidden.

I just didn’t think people knew. Or maybe they knew but didn't know how to approach me. It’s always hard, especially for a 10-year-old, to know how to deal with someone who lost their sibling. But it came out. And then, I think Alan Berliner—you know him, right, his filmmaking?

Jay Rosenblatt wearing all-black climbing his school’s fence. From Jay Rosenblatt’s ‘When We Were Bullies.’ Courtesy of HBO.

D: Absolutely. Great filmmaker.

JR: Yeah, a master. He watched a cut of the film and really loved it, but he did give me one note. He said, "I’d like to see you bring in more vulnerability." Because at that point I talked about vulnerability from, I would say, a mental perspective. From the head, but not as much from the heart. So I thought, Yes, he’s right. I’m talking about vulnerability but I’m not fully vulnerable here. How can I do that? And then it became clear that one way into that would be to bring in the situation I was in at that age, because my brother had died a year before.

Now, some of the other aspects, again, really just happened. For instance, we had no idea that the gate would be locked at the school and that we’d have to climb over the fence. That was a very vulnerable thing to do and to put in the film because I felt really awkward. I felt like I was going to hurt myself. But also, there was a humor to it, and I liked having that kind of playing with the tone of the film—being about something serious yet also having a playful aspect to the filmmaking. I always feel that when you bring humor into a film, even if you want to say something more serious, it opens people up and they can take it in more. It goes in deeper.

So I think those were a couple of examples of vulnerability. I felt like it was the kind of film where I wanted to have the viewer really relate to what I was saying. I think the more vulnerable I was, the more likely that would be. That was at least my theory as I was moving along in the film.

And you’re right that some of my films have been personal, especially the ones I’ve done with my daughter, and I’m in them. She’s obviously more in them, but even presenting her in a film that the public sees, that strangers see, is very…It takes a lot. It’s not an easy thing to do as a parent. Even though I do have a newer film with her, I stopped doing it for a very long time.

And for The Smell of Burning Ants I didn’t even want to use my voice. I wanted to be more behind the scenes. So it’s been a 25, 30-year process of feeling more comfortable being a part of the film and being on screen. I was going on this search, this journey, and I didn’t want to do it just in voiceover.

D: Yeah, I found it interesting that you admit to hating the sound of your voice—and then proceed to narrate the film! So are there scenes you find particularly difficult or even cringeworthy to sit through—perhaps were even tempted to edit out?

JR: Well, you have to remember that when I said I hated the sound of my own voice, that was for The Smell of Burning Ants. So that was a long time ago. I think I’ve gotten somewhat over that, but you’re bringing up a good point.

D: Couldn’t you have had your co-star Richard Silberg narrate it?

JR: That did cross my mind at one point, but then I felt like it would be more his film. He’s in it a lot and he tells some of the crucial stories. He was such a good storyteller, I thought, I have to use him. He’s actually better on-camera. But I didn’t want to narrate the film on-camera. I wanted to be off-camera, where I felt I had more control over my voice.

Also, I had a good friend of mine, filmmaker Caveh Zahedi, direct me. Which helped a lot because in early cuts of the film I think I was a little too monotonous. I didn’t bring enough emotion into the piece. He really helped with that—which made me feel better about my voice because I felt my delivery was pretty good. Part of it wasn’t just the quality of my voice that I didn’t always like. It’s hard to deliver lines, especially when it’s your own story. It really takes someone else to help you through that.

But there are moments in the film, like when I’m on-camera calling my teacher, where I didn’t feel like I had as much control over my voice. It’s kind of high-pitched and it really bothers me. But then I thought, I’m getting too old to worry about things like that.

D: I actually like that scene because you kind of sound like a little kid addressing his teacher.

JR: I couldn’t believe I got through to her finally! I wasn’t so nervous talking to her. Well, maybe I was a little bit. Actually maybe I was. But it was just so hard to get through to her. She just wouldn’t pick up.

D: I’m surprised that scene is hard for you to watch.

JR: Just voice-wise—the voice, not the scene. I was happy that I got through to her, and I felt good about the questions I asked. Her responses were perfect. But when I was delivering the voiceover I could modulate my voice a little. In those live-action scenes, they were what they were. But you might be right. Maybe it was just nervousness that brought the pitch up and I thought, "Oh, my God, that sounded bad!"

D: So did being the star of the film push you to see those in front of the lens in a way you maybe hadn’t before?

JR: Actually, I don’t see myself as the star of the film. It’s funny that you put it that way. I see Richard as the star.

D: Really? It’s your story.

JR: Well, he’s in it a lot with me and he’s on-camera much more than I am. It is and it isn’t his story. I really think the event is more his story than it is mine, because he has the memory of it. I have such a vague memory of the event, of the incident. So I always thought of him as the main focus. But you’re right in that, especially through voiceover, I’m leading the whole story, the whole film. I’m the one engaging with the viewer. So, yeah, that’s clearly my story and my film.

But because I didn’t appear on-camera that much, I don’t think it had that effect that you’re getting at. I think I found a greater appreciation for voiceover and how hard that is. I’ve used Richard in three films, this being the third. I know I don’t stop until I feel like I’ve gotten the delivery that I want. So I definitely see how hard it is to get it right, because you’re not sure what the director wants exactly. Which is why it really helped to bring Caveh in.

D: Bringing in an outside director is an interesting choice.

JR: Yeah, I can think of many films where they should have done that! Delivery is so hard and it’s very important.

D: Actually, this film also made me think that more documentarians should put themselves in front of the lens, so to speak. In general, vulnerability and doubt make for good filmmaking. So did going on this spiritual journey—as I think you admitted to me when I interviewed you during the film’s 2021 Sundance premiere—change how you think about the craft of directing itself?

JR: I don’t think so. I think this story just really begged for me to tell it and to be more in it. And I’m not sure I actually agree with you that more documentarians should be in their films. A lot of times it doesn’t feel organic. A lot of people feel they should do that and—

D: I’m thinking more in metaphorical terms. Like, take a look in the mirror before you begin production.

JR: Oh, I see. Yes, I think you’re right about that. But I think you’re getting more into the ethics of documentary filmmaking. Which really gets to one of the core aspects of my film—deciding not to interview the person that was bullied. I think that really speaks to that decision more than anything.

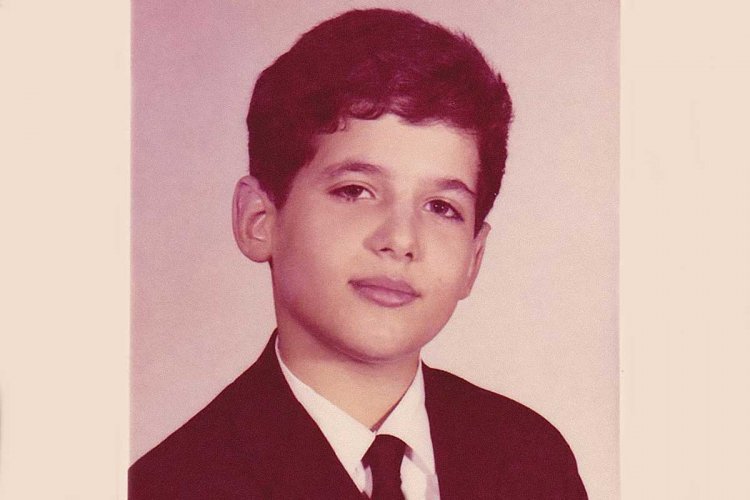

An old sepia-toned yearbook photo of Jay Rosenblatt as a fifth grader. From Jay Rosenblatt’s ‘When We Were Bullies.’ Courtesy of HBO.

D: Did that happen organically or was it more of a eureka moment?

JR: I would say both. It definitely didn’t start out that way. If you look at my original grant proposal, I had every intention of trying to find (the bullied) Richard—and that’d be the culmination of the story. What happened is that I did this one screening really early on—not even a rough cut, more of a rough assembly. Just a few scenes that I had strung together. One of the conditions for receiving this arts commission grant was, I had to do a public screening—which I don’t normally do. I prefer one-on-one screenings with people I trust. Anyway, I’m so glad I did this public screening because it actually was quite helpful.

In the original cut, the person that was bullied appeared in the film—not as an adult, but his photo was one of the photos. A couple of people felt uncomfortable seeing him. When they said that, I knew. I felt it in my body. I too was feeling a little uncomfortable but hadn’t quite gotten to that place.

So when they said that, I thought, "You know what? I don’t feel comfortable showing him here." And that led to me thinking I needed to protect his identity, his privacy. Which led to, "I don’t even want to impose this film on him." This is not really about him, this is about us. And I say that in the film.

So I decided to share that revelation in the film itself, because the film is very transparent. I’m kind of telling people what I’m going through as I’m making it. For the most part, everything actually happened the way it happened. And ultimately, I felt like it was the right decision for other reasons as well. For example, when we only see his silhouette, or his face blurred, I think that allows the viewer to enter the film a bit more. They can then bring their own self into it, or maybe they bring a person they remember bullied in their lives. I don’t think that would be the case if you actually saw the person in my film. I think this creates more universality than it would otherwise. So, yeah, it was a very momentous decision for the film to go in that direction.

D: Using the photo where he’s cut out, and you and your classmates replace him in the frame—that’s a really powerful choice.

JR: I think there’s maybe an unconscious effect, too, with that particular technique. Bullying is not black and white. Many of us have been on both sides. I’m complicit and I’m a collaborator. But I was also bullied growing up. I think many people have experienced it both ways, and that’s part of the dynamic. The psychology behind complicity is fear of being bullied.

D: So what are your ultimate hopes for the film now that it’s about to air nationwide on HBO?

JR: Well, already a lot of people that have seen it feel compelled to tell me about their experience—which is one of the things I was hoping for, that it would open up that conversation.

D: Perhaps putting yourself on screen makes it safer for them.

JR: Yeah, I totally agree. I don’t know what to expect exactly, but I hope it’s in a way more of the same—that people are very touched by it and that it leads to some inner healing. That’s my ultimate goal.

D: Are you expecting the unidentified Richard, who told you he grew up to have a long career as a television producer, to finally be in touch again?

JR: It’s hard to know. Will he even get wind of it? Will he reach out to me? Certainly he did for The Smell of Burning Ants. Though after I sent him the DVD, he never responded, and I didn’t push it at all. I thought, OK, he’s probably telling me something here. Maybe he wants to just put that away and not deal with it—and I want to respect that. So, who knows? I mean, I’m open to that, of course. What would be difficult is, if it brought up a lot of pain for him. But if he just wanted to talk and tell me what things were like for him, I would love to hear that. Oh, and just so you know, he was a television producer. I don’t think he is anymore.

Lauren Wissot is a film critic and journalist, filmmaker and programmer, and a contributing editor at both Filmmaker magazine and Documentary magazine. She's served as the director of programming at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival and the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival, and has written for Salon, Bitch, The Rumpus and Hammer to Nail.