India's Truthtellers: A Half-Century of Independent Doc-Making in a Turbulent Political Landscape

During the 2022 Academy Awards season, now overshadowed by the infamous slap, an Indian film became the first documentary from the country to get a nomination. Directed by Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh, Writing with Fire (2021) focuses on Khabar Lahariya, a rural media outlet run by Dalit women. Dalits are at the bottom of the country's brutal caste system, one of the oldest social hierarchies in the world. The film, which took five years to make, won several international awards, including an Audience Award and a Special Jury Award at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. Shortly before the Oscar ceremony, the news outlet it documented issued a statement, disputing some of the film’s narrative preoccupations.

Recognizing Writing with Fire as “a moving and powerful document,” the statement claimed that “its presentation of Khabar Lahariya as an organization with a particular and consuming focus of reporting on one party and the mobilization around this, is inaccurate.” The political party it refers to is Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has been in power at the national level and in several states since 2014. Independent global organizations have claimed that BJP’s tenure has resulted in a backsliding of democracy in the country, diminished freedom of the press, and increasing violence against religious and caste minorities such as Muslims and Dalits. The dispute over Writing with Fire demonstrates, yet again, the fraught landscape in which journalists and documentary filmmakers operate in India.

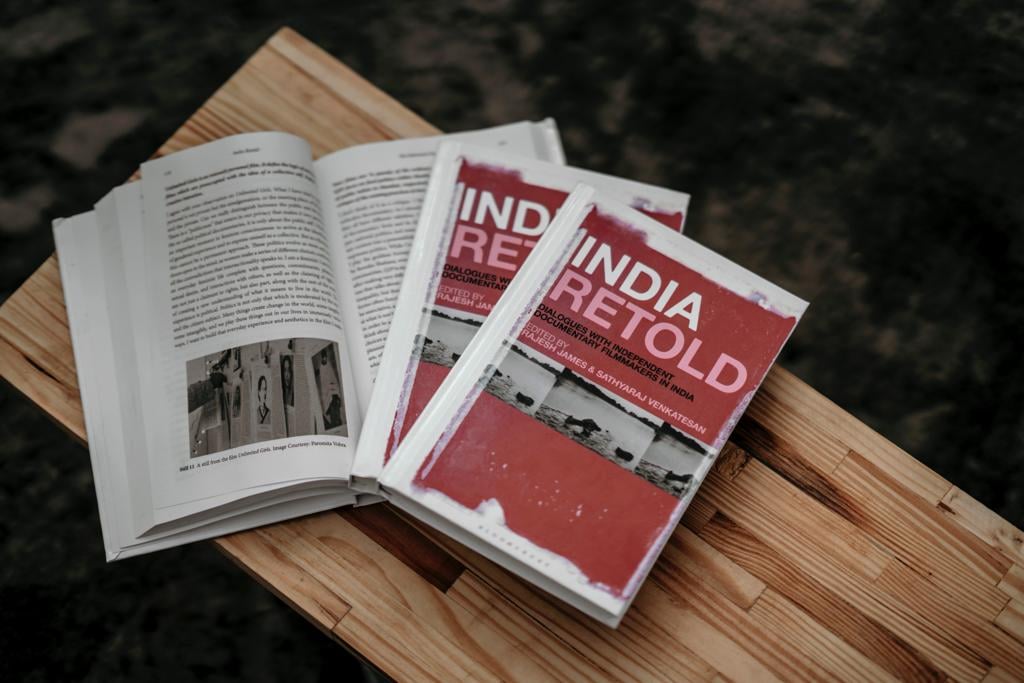

In this landscape, India Retold: Dialogues with Independent Documentary Filmmakers in India, edited by Rajesh James and Sathyaraj Venkatesan, is an important and timely intervention. The book compiles interviews with 30 contemporary documentary filmmakers, decoding the multiple ways in which they are responding to India’s fraught and ever-changing society. Its contents page reads like a roll call of some of India’s best-known documentary filmmakers—Anand Patwardhan (whom the editors describe as “the father of independent documentary films in India”), Saba Dewan, Sanjay Kak, Paromita Vohra, Sridhar Rangayan, Nakul Singh Sawhney, and others.

“The book compiles interviews with 30 contemporary documentary filmmakers, decoding the multiple ways in which they are responding to India’s fraught and ever-changing society.”

Challenges of Classification

The sections are arranged under different sub-heads—“Decoding Ideology: Nationalism, Communalism, and Its Critiques,” “The Subversive Eye: Gender and Sexual Identities,” “Documenting Inequality: Casting the Caste,” “Remain True to the Earth: Mapping the Post-Natural India,” and “Thinking through Regions: Nation and Its Discontents.” Evidently, these sections are an attempt to classify the filmmakers according to their subjects, such as the rise of the militant Hindu right-wing, gender discrimination, caste, ecology, and post-colonial nationalism. However, such an attempt, though helpful, can never be fully satisfactory because many of these filmmakers have explored more than one subject throughout their careers, or even in individual films. For instance, Patwardhan has documented in his film Ram Ke Naam (In the Name of God, 1992) the Ram Temple movement of the late 1980s and 1990s, which was an ahistorical campaign by the BJP for the construction of a temple to the Hindu god Ram in the northern Indian city of Ayodhya. But he has also directed Jai Bhim Comrade (2011), a lengthy contemplation and narration of Dalit lives and movements of self-assertion.

The editors recognize the difficulty of classification in their introduction: “The objective of this book is to trace, explore, and engage with such filmmakers who, though they defy any easy classification, unsettle the conventional understanding of the relationship between individuals and the state apparatuses by deploying critical aesthetics and medium-specific affordances.” The editors also claim that the documentary filmmakers “retell India”—narrating the nation through alternative stories that focus on suppressed cultures, different geographies, and othered desires.

This is something documentary films in India have done since the advent of cinema in the country in the first decade of the 20th century. Cinema scholar Ashish Rajadhyaksha, in his book Indian Cinema: A Very Short Introduction, identifies the 1911 visit of British monarch King George V and Queen Mary to India as an important event in the history of Indian cinema: “It was filmed by two dozen film crews, and although pride of place went to Charles Urban’s feature-length Kinemacolour film titled With our King and Queen Throughout India, in the throng of cameramen were three venerable Indian crews: those of Hiralal Sen, S. N. Patankar, and the Madan Theatres.”

James and Venkatesan recognize this historical moment in the introduction, adding cinema pioneer Hiralal Sen’s documentary of protests during the first Partition of Bengal (1905-11), as well as films on nationalist leader MK Gandhi’s anti-colonial movements as examples of a different narration of the nation. They also provide a brief history of films produced by the Film Division, set up by the Indian government after independence in 1947. However, their focus area is the period from 1970 to 2020. “The present book argues that there was a veritable turn in the practice of independence in the 1970s and in subsequent years,” they write, identifying Patwardhan, Tapan Bose, and Suhasini Mulay as the pioneers of this change.

"This book...will become essential reading for researchers in Indian film studies."

The Best of Times, The Worst of Times

The reason for this “veritable turn” was the socio-political churn that the country went through in the 1970s. By the mid-1960s, the hopes of quick economic development and social justice that India and its leaders had cultivated at Independence had been dashed, and the various fault lines in the fabric of the nation—religion, caste, language, gender, class—were threatening to tear it apart. A violent Maoist insurgency had begun in the eastern state of West Bengal and spread to other parts of the country. Many groups in the restive Northeast were challenging New Delhi’s authority. The Indian government’s response to these challenges was often knee-jerk counter-violence, and police and army action.

Yet, despite all this, the 1970s began on a hopeful note for the country. In 1971, India’s third prime minister, Indira Gandhi, led the nation to a decisive victory over Pakistan in the Bangladesh War of Independence and managed to stop a genocide, which has perhaps been best documented by American journalist and academic Gary J. Bass in his book The Blood Telegram. The period of hope, however, was short. Faced with rising protests, Gandhi declared the Emergency on June 25, 1975, when she imprisoned political opponents, censored the press, and ruled by decree. After the Emergency was lifted in 1977, a strong democratic movement unseated her, but she was back in power by 1980.

It was in the crucible of these troubled times that filmmakers like Patwardhan emerged. In his interview with the editors of this volume, he claims that he became a filmmaker because of the Emergency, although he had not planned to be one. “At that moment the Bihar movement had begun. It was a nonviolent student movement, which turned into a mass movement against corruption and other social evils like dowry and caste. I went there to see what was happening and got involved in it.” He narrates the challenges of making what would become his first film, Waves of Revolution (1975), such as lack of equipment and even stock film, as well as editing. By the time he finished the film, the Emergency had been declared. “We couldn’t show the film openly because of the fear of ending up in jail,” he recalls. The film was eventually smuggled out of India and became part of anti-Emergency propaganda.

But the climate of censorship did not end with the Emergency. In fact, as Patwardhan knows, it has only increased in recent times, with right-wing activists successfully agitating and stopping the screening of his films at different venues across the country. “I am not a revolutionary who believes in the armed overthrow of the state,” he tells his interlocutors. “I am fighting a constitutional battle. We have a good constitution that gives us a lot of weapons.”

A Necessary Volume

India has consistently produced the largest number of films in the world since at least 2007 and was valued at INR 183 billion ($2.4 billion) in 2020, according to research by Statista. While Indian cinema is best known in the West for the Mumbai-based Hindi film industry, there are at least 20 major film industries in other languages such as Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, Punjabi, Marathi, Gujarati, Bengali, and Bhojpuri. The astronomical budgets of these films and the massive star power of actors mean that they almost monopolize the attention of the mass media. However, with the increasing influence of Hindu majoritarianism in the mainstream film industries, it has become even more important to protect the space for independent cinema, writes film scholar Ashvin Devasundaram.

In such a climate, the importance of a book such as India Retold cannot be overstated. In recent years, there have been several on independent documentary filmmaking in India, such as Filming Reality (2015) by Shoma A. Chatterji, Documentary Film in India: An Anthropological History (2017) by Giulia Battaglia, and A Fly in the Curry (2015) by KP Jayasankar and Anjali Monteiro. This book is an important addition to the list and will become essential reading for researchers in Indian film studies.

Uttaran Das Gupta is a New Delhi-based writer and journalist. He has published a book of poems and a novel and also writes a popular weekly column on the intersection of cinema and politics. He teaches journalism at OP Jindal Global University.