In December 2020, the Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that has held an absolute majority in Parliament since 2014, approved the merger of four hitherto distinct, publicly-funded film units—the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), the Films Division (FD), the Children’s Film Society of India (CFSI), and the Directorate of Film Festivals (DFF)—with the state-owned, for-profit National Film Development Corporation (NFDC). This came into effect on March 30, 2022.

Most of the film units were established by independent India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and, though technically under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB), they tended in practice to enjoy a large amount of independence, often funding and preserving works critical of ruling parties and the status quo.

The NFDC was incorporated in 1975 to promote “a good cinema movement” by facilitating the production, distribution and exhibition of the so-called New Indian Cinema. “The merger of Film Media Units under the Corporation,” the government’s press release said, “will ensure a balanced and synergized development of the Indian cinema in all its genres—feature films, documentaries, children’s content, animation and short films and will lead to better and efficient utilization of existing infrastructure and manpower [sic].”

The sheer ambiguities of this merger—an absence of dialogue with stakeholders, who range from film practitioners and historians to cinephiles and students; the reluctance to release documents and reports; the refusal to respond to requests for information; the uncertainty over the future of archives—now lead many to question the motives of a government that, as its critics allege, has made no bones about its willingness to remake history and manipulate memory.

“We all know the current regime’s special love for annihilating institutions which have played a key role in the making of independent India,” says Sudha Tiwari, an assistant professor at UPES, Dehradun. “Cinema—to be more precise, the Hindi film industry—has always been at the center of their attempted cultural makeover of India. What we see today is part of the larger effort to change the film industry and force it to surrender to this regime’s ideological narratives, and they are succeeding too.”

The BJP has deliberately positioned itself as the party taking India to its promised neoliberal Hindu destiny—an India made great again!—away from what it abhors as the ills and missteps of the secular, socialist Nehruvian vision. Because the film units and their extensive archives reflect that old legacy, many filmmakers and academics across India have been dreading this merger. "By the government’s own admission, the NFDC has been a loss-making unit that was supposed to be disinvested from and shut down," say National Award-winning filmmakers Shilpi Gulati and Prateek Vats. “The FD, CFSI, NFAI and DFF have mandates to serve as public institutions that produce, promote and safeguard Indian cinema heritage. Why should the MIB merge them into an umbrella corporation under the NFDC?” The government recently privatized the national carrier, Air India, after it was declared a ‘sick PSU’ [Public Sector Undertaking]. If, someday, the NFDC is declared sick and sold to the highest bidder, who gets to access these resources then? Will the archives be sold over time to generate money? Might they deteriorate from unconcern?

The haze of corporatese blanketing the government’s pronouncement fails to camouflage its murkiness. Ostensibly, this merger with a struggling corporate entity will reduce “duplication of activities” and lead to “direct savings to the exchequer,” but this is a curious claim. The four film units perform discrete and specialized functions, all in the public interest, as custodians of the national cinematic heritage.

In 1948, one year after independence, a number of colonial-era documentary divisions—the Film Advisory Board, the Army Film and Photographic Unit, Information Films of India, and Indian News Parade—were combined to establish India’s largest repository of the moving image, the Films Division. Headquartered in Mumbai, the FD made documentaries and newsreels, filming the process of decolonization and nation-building; this will now be done under the “Production Vertical” of the NFDC.

The FD is the “sole custodian,” as filmmaker Shyam Benegal once called it, “of the archival history of this country on film.” It has produced at least 5,200 documentaries and over 2,500 newsreels.

"Why should it be closed down,” ask Gulati and Vats, “when it has been the lifeline for documentary films in India?" Tiwari believes “the FD newsreels of the Nehruvian period are in major danger.” In a country where filmmakers and exhibitors are increasingly under pressure to self-censor for fear of vigilante mobs covertly or overtly supported by the state, the lack of detail about the fate of these treasures feels very much like a further indictment of the state’s attitude to cinema and its preservation, and of its disregard for the audio-visual history of modern India. On the phone, present employees sound clueless about the future of the archives.

The Children’s Film Society of India was set up in 1955 to produce and exhibit films for children. A luminous gallery—Mrinal Sen, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Sai Paranjpye, M.S. Sathyu, Shyam Benegal and more—has made films for the CFSI over the decades, but since 2018, this unit has been without a chairperson and no new films have been approved for production. On December 13, 2021, Ravinder Bhakar, the CEO of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), was given charge of the CFSI. Three days earlier, he had been made the Managing Director of the NFDC and the Director General of the FD. Bhakar is a career railway services bureaucrat.

The Directorate of Film Festivals was created in 1973 and organizes the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF), the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in Goa, and the National Film Awards (at which it also presents the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, India’s highest film award). “The takeover of the Directorate of Film Festivals and its branches across the country is, of course, primarily ideological,” asserts documentarian Anand Patwardhan, “for a regime that wants to hide its crimes of commission and omission cannot afford a thriving festival circuit where aspects of the truth may emerge through cinema, be it documentary or fiction. So control must be exerted on both the films we see in India and the films we officially allowed to go abroad for the rest of the world to see.” In the new scheme of things, the DFF has been absorbed into the “Promotion Vertical.”

The National Film Archive of India operates mainly out of the beautiful Jayakar Bungalow in Pune. Once the residence of the first Vice Chancellor of the University of Pune, this facility houses the largest collection of fiction films in the country. Established in 1964 under the visionary curatorship of the archivist P.K. Nair, the NFAI has traced, acquired, and archived thousands of films, books, and memorabilia. “Archiving is a highly specialized endeavor,” says Moinak Biswas, Professor of Film Studies at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, “and Prakash Magdum was doing exemplary work. It is really unfortunate that he had to go because of the merger.” Magdum was, until recently, director of the NFAI, and it is through his unwavering passion that the archive managed to acquire—from the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé in Paris—the 100-year-old, five-reel Behula, produced in 1921 by Madan Theatre during Kolkata’s great silent film era. He was also instrumental in recovering the original 35mm negative of Satyajit Ray’s Pratidwandi (The Adversary), the NFAI-restored version of which was screened at Cannes this year.

The preeminent archive of Indian cinema, the NFAI has reels dating back to 1910. This vital resource has now been sucked into the NFDC under the “Preservation Vertical,” and will no longer have an autonomous director. Various officers have also been removed. “Thus the functioning of the NFAI,” filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan wrote with alarm recently, “has come to a standstill.” Repeated phone calls—to their headquarters in Pune, as well as to regional offices in Bengaluru, Kolkata and Thiruvananthapuram—go unanswered.

The National Film Development Corporation, now in charge of all film units, has had one foot in the grave since the 1990s. In 1980, the NFDC was combined with the pre-existing Film Finance Corporation “to create a financially viable organization,” as the Report of the Working Group on National Film Policy put it back then, “but because of its developmental role, it [did] not aim at profit maximization.”

“The NFDC has been facing the pressure of being commercially viable since its inception,” says Tiwari, who researched the corporation for her PhD. “By the 1990s, it was almost regarded as a ‘sick’ unit, and filmmakers had raised concerns over the NFDC being killed in the zeal of privatization. By 1992, there was discussion on winding it up.” There have since been periodic calls for downsizing or shutting down the NFDC. “It has been surviving since the 2000s only because of its annual Film Bazaar [South Asia’s largest co-production market],” Tiwari continues. “With the added burden of NFAI/FD/CFSI/DFF, Film Bazaar may be affected; the money will have to be directed to the management of these institutions.”

Although the MIB maintains that “the ownership of the assets available with these units will…remain with the Government of India,” Gulati and Vats, who drafted a letter to the ministry signed by over 1,500 filmmakers opposing the merger, are unsure. “It would help if the government acknowledges that it is a custodian of public assets and not their owner, and has to consult all the stakeholders affected by the merger before taking such a drastic step,” they add. Their letter has received neither acknowledgement nor reply.

“The financial bonanza available by selling off public assets is all too real,” says Anand Patwardhan, “but so is this government's anxiety to keep the audio-visual world on a tight leash.” Patwardhan believes the NFAI and the FD have been taken over primarily with “the aim of rewriting history, but with the additional lucrative option of selling off land and assets both for profit, and to hand over some assets to ideological partners like the RSS and its many offshoots.”

The RSS, or Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, is a Hindu nationalist organization with fascist roots. Estimated to have between five and six million members, it is the ideological progenitor and moral guardian of the BJP. “The takeover of the Children's Film Society should not be surprising,” Patwardhan argues, “seeing the emphasis the RSS has always placed on controlling the impressionable minds of the young.”

It is a legislative quirk of Indian governance that cinema falls under the remit of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and not, say, the Ministry of Culture. In the capricious eyes of the Indian state, film has always been an instrument of propaganda, an inheritance from the British colonial government. The current Minister of I&B—who publicly encouraged violence before the Delhi elections in 2020, and who now has absolute power over all public film units in the country—has called cinema “India’s greatest soft power” and stressed its role in “nation-branding initiatives.” “All the so-called ‘media units’ are the most vulnerable,” says film scholar and curator Amrit Gangar, “as they are under complete control of the MIB, with no autonomy. They are powerless against ministerial orders.”

Gangar, who founded a database called Datakino for the FD archives, finds it strange that film archiving is going through “vertical integration…with a corporation whose function was film dissemination and which has lost its existential backbone.” In fact, he argues, “There should be several film archives because the Films Division has a massive collection of films and they need to be conserved by a separate archive—negatives [both sound and visual] need the utmost care…. Film archiving is a highly centralized activity in this country, which should be decentralized, and we should have archives in all states, and, in this time of technological convenience, their collections should be accessible to interested citizens.”

“Centralization is always a problem,” Professor Biswas insists. “Why would you destroy autonomous bodies? Institutions develop special focus and specific skills. Autonomy is essential for maintaining that.” Indeed, Patwardhan believes this merger—he prefers “takeover”—is “nothing short of an assault on our Constitution.”

The opacity surrounding the merger lends particular credence to suspicions of an ideological makeover of our cinematic institutions. After the NFDC’s financial viability was questioned in 2018, an Expert Committee on the Matter of “Rationalization/Closure/Merger of Film Media Units” was tasked to evaluate the workings of the five film units. Chaired by the then Chief Information Commissioner Bimal Julka, the committee submitted its report to the government in June 2020, which announced the recommended merger six months later. Despite repeated appeals by the film fraternity, academics, and other interested parties, the government refused to release the Julka Committee report to the public before January 2022, by which point the NFDC had already begun to subsume the other units.

“This report is hogwash,” says Jawhar Sircar, Member of Parliament, former Secretary to the Government of India, and former CEO of India’s public broadcaster Prasar Bharati. As a former bureaucrat intimately familiar with the workings of government departments, Sircar believes the Julka Committee report says exactly what the government wants to hear. “It’s pretty obvious they want to commercialize the NFDC. This is the typical product of a bureaucracy that doesn’t know a film reel from a boom mic.”

This fugitive process almost certainly shares its DNA with the government’s concurrent attempt to make film certification and censorship more draconian. The Expert Committee on “Broad Guidelines/Procedure for Certification of Films by the CBFC,” which was chaired by Shyam Benegal and included reputed filmmakers like Goutam Ghose and Kamal Hassan, submitted its report to the MIB in April 2016 recommending that the CBFC stop acting like a censor board and “transition into solely becoming a film certification body.” Not only was this ignored—and the report made public only in 2021—the government last year also abolished the Film Certificate Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), the specialized court of redressal for filmmakers who disagree with CBFC certifications. It now intends to amend the Cinematograph Act of 1952 to be able to retroactively change a film’s existing certification.

“The proposed Cinematograph [Amendment] Bill 2021 is another mode of extreme centralization; it offers uncontrollable power to the state,” says cinephile and film critic Parichay Patra. “It may affect an already-threatened federal structure and, in the name of curbing piracy, it intends to develop a surveillance regime with unforeseen consequences for cinephilia in India.” Patwardhan alludes to a previous BJP government that in 2003 forced the Mumbai International Film Festival to demand censor certificates from Indian entries. “Following widespread protests, this censorship clause was withdrawn, but a much more clever ruse ensured that all uncomfortable films, like Rakesh Sharma's Final Solution, on the 2002 pogrom of Muslims in Gujarat, were simply ‘not selected,’ as the government-appointed selection panel found it ‘lacked merit.’”

At the International Film Festival of Kerala in 2019, screenings of Patwardhan’s Vivek/Reason were initially disallowed by the central government. “A year later, the selection panel at MIFF rejected the film,” he informs me, “despite it having won the Best Documentary Feature Award at IDFA.”

“This is a regimentation of the cultural realm,” Professor Biswas concurs, “an attempt at greater control.”

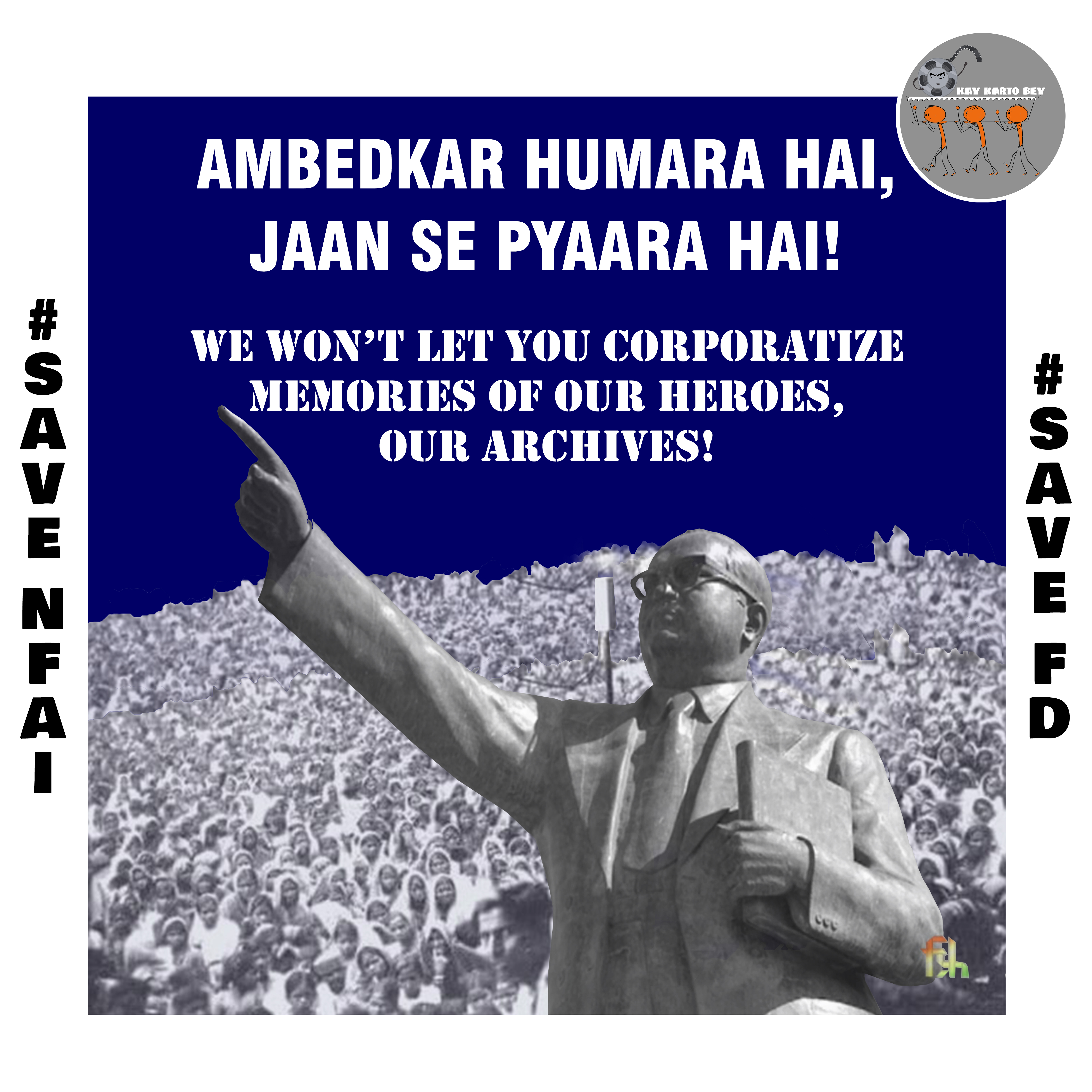

“The question of the archive is not…a question of the past,” wrote Jacques Derrida. “It is a question of the future, the question of the future itself.” To stop what Patwardhan calls “a highway robbery of public assets in broad daylight,” a group of filmmakers, archivists, scholars and media students have started Kay Karto Bey (What are you up to?), a campaign that demands these archives be declared a freely accessible national heritage. While it has had some success, and the government has promised to implement a National Film Heritage Mission to preserve and restore Indian films, there is still no clarity on how the NFHM will work.

Storehouses of history and public memory are the building blocks of national narratives. Power flows through the national archive, the state museum, and the public library. Archive, from arkhē, recalls the origin and the authority of recording, to begin as well as to rule. Unlike our first prime minister, Modi does not like criticism. For the BJP to mold the future of the world’s largest democracy in their image, they need to remake its memories.

But forgetting is so long. Recently, seven centuries of archives at the Public Records Office in Dublin, obliterated in 1922 during the Irish Civil War, were recreated virtually.

History can be hard to shake off.

Sudipto Sanyal is a writer in Kolkata. His work has appeared in The Economist, The Smart Set, The Hindu, Mekong Review, et al. He hosts a midnight show called Songs of Comfort for Hypochondriacs and Panicking Lovers, on Radio Quarantine Kolkata.