At BlackStar, everyone is colluding to envision the future of filmmaking. The beloved Philadelphia film festival operates like a spirited convening in which industry veterans and first-time cinephiles gather to watch films by Black, Brown, and Indigenous filmmakers. The programming this year, as always, was robust in both thematic interconnectedness and quantity. Each day offered panels, screenings, and opportunities to prioritize wellness. It continued its longstanding recognition as the “festival to be at” among my cohort of film lovers. It was wonderful to run into faces old and new and politic in front of the various screening venues at the festival. This spilled into the city of Philly itself, going with groups to get coffee or lunch, cross-compare notes about what we saw, and engage in the kinds of unbridled cinephilia that allow you to achieve deeper interrogations of the form. The festival invites curiosity and camaraderie to absorb, to critique, to get a feel for the trajectory of Black, Brown, and Indigenous cinema and the artists creating it. Waiting in line for a screening could mean striking up conversation with documentary filmmaker Ada Gay Griffin or your former cinema studies classmate.

The importance of BlackStar is not lost on me as the industry slowly recedes in prioritizing the voices of marginalized folks in a world sliding into fascism. BlackStar’s continued expansion into year-round programming through BlackStar Projects—the Philadelphia Filmmaker Lab’s $50,000 production grants for local filmmakers, the print journal Seen, the William and Louise Greaves Filmmaker Seminar—suggests the festival’s evolution from annual gathering into sustained infrastructure. At the festival, the sixth BlackStar Pitch awarded US$75,000 in production funds to a documentary filmmaker (this year’s winner was Kya Lou, for Hysterical). Early career filmmakers, many of them previously supported by BlackStar, returned to the program alongside those who carved a path for them to exist, such as Black cinema legends Zeinabu irene Davis and Charles Burnett, who presented restorations of their respective masterpieces, Compensation (1994) and Killer of Sheep (1978).

BlackStar demonstrates the significance of convening. There’s something lovely about being in a place where you can see new voices emerge and sit at the feet of their elders, many of whom joined in conversations on the Daily Jawn stage at the Kimmel Center, which acted as an important place of gathering for us all throughout the festival. To gather there felt like a salve in a world that deepens its attempts to seduce us all toward individualism, to which I resist, as the making of new worlds can’t be done in isolation.

Before you even see an image move at BlackStar, be it virtually or in person, you’re met with a festival bumper that includes a title card with a quote from The Bombing of Osage Avenue (1986) by Toni Cade Bambara:

The original people who blessed the land were the Lenni Lenape or Delawares, the eldest nation of the Algonquian Confederacy… Others would come to rename it— would claim it with their guns and their plows, their dreams. Africans came too—captive, but with dreams of their own.

This sets the thesis for the festival’s theme, Cinema for Liberation, one deeply reflected in the programming and in all of the films, not just the documentaries.

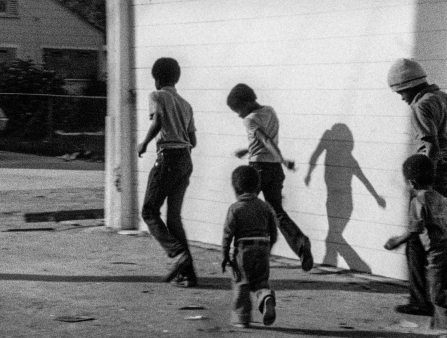

Killer of Sheep.

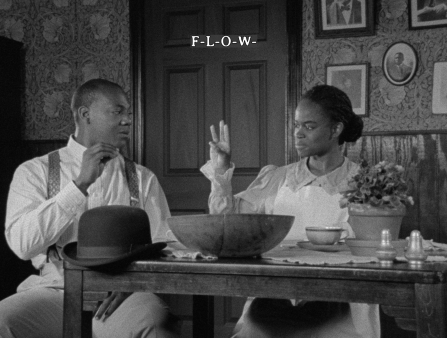

Compensation.

TCB – The Toni Cade Bambara School of Organizing.

So it was only fitting that Louis Massiah’s documentary about Bambara’s life, TCB – The Toni Cade Bambara School of Organizing, opened the festival. Massiah, a Philly legend in his own right, and founder of the Scribe Video Center, was also one of Bambara’s collaborators. The two co-directed and Bambara wrote the documentary The Bombing of Osage Avenue, a record of the bombing on MOVE’s house on Osage Avenue by the Philadelphia PD that killed 11 members (five of whom were children) and destroyed 61 homes. We who are cultural workers have much to learn from Bambara. It’s not easy to capture such an expansive life in a film, especially about an iconic figure in the pantheon of Black feminist literature, filmmaking, organizing, dreamweaving, and more. To do so, Massiah assembles a chorus of those who love her most to speak in tandem with her. Bambara’s voice narrates the journey of her own life, as do her childhood friends, sisters, and students. The resulting film shows that at every juncture of her life she sought to feed herself and her community a steady diet of art and education with great intentionality.

“Art for people’s sake”—in one scene, we see Bambara’s name tag with “NOVELIST” typewritten and scratched out, replaced in her own handwriting with “cultural worker.” Her position as an artist and multidisciplinary storyteller served to elicit change or, in her words, to “make revolution irresistible.” Art’s accessibility mattered to her, an idea that still resonates today as we see fewer working-class people in creative fields. The film also chronicles her move to Atlanta’s Vine City, a lower-income area where, despite proximity to longstanding academic institutions, Bambara and her collaborators developed their own curriculums and spaces. Black bookstores and community centers—Timbuktu, the African Eye, and even the Neighborhood Art Center—became important venues to share art with folks in the community. Most striking was archival footage of Bambara speaking authoritatively about these spaces’ objectives, emphasizing not only the development of the next generation of artists but also the cultivation of a critical audience, a goal that still feels necessary.

These acts of convening, sometimes within her home through the Pamoja Writers Guild, opened doors for expanding consciousness. The breadth of workshop attendees is best explained by one participant: “Some of us were students, some of us were nurses. One was a bus driver who wanted to write.” For Bambara, being an artist meant being among your people—not isolated, fussing over details alone.

This principle carried over into her forays into filmmaking and beyond. As Zeinabu irene Davis recalls about Bambara’s approach to cinema, “Toni Cade Bambara was always about the untold stories. That was Toni to me: untold stories, unheard voices, or just the everyday folk you don’t get to hear all the time.” Her self-fashioning (adding Bambara to her name), emphasis on spreading knowledge, and creative drive are also hallmarks of other festival documentaries about Black visionaries charting pathways to greater realities. Like Bambara, they understood that they would often need to create entirely new worlds.

Louis Massiah (standing) at BlackStar. Image credit: Deonté Lee

Sun Ra: Do the Impossible.

Seeds.

“If you find Earth boring/ just the same old same thing/ come on sign up with/ Outer Spaceways Incorporated,” June Tyson declares in Sun Ra’s song “Outer Spaceways Incorporated.” This invitation from Sun Ra reached my ears decades after his earthly death, when I first discovered his music for myself, proof his mission continues. Christine Turner’s Sun Ra: Do the Impossible chronicles his life as bandleader, Saturnian angel, and nurturer and creator of new realities. An opening title card lets us know that all the music in the film is by Sun Ra, demonstrating both his catalog’s breadth and its ability to collapse and expand time through, in part, his deep musical study. The documentary begins with his love of big bands like Duke Ellington, with whom he shared his work, and Fletcher Henderson, whom he later studied under. His audacious spirit emerges early.

Born Herman Poole Blount, Sun Ra was imprisoned for dodging the WWII draft after being inspired by the words of DuBois and Gandhi, decades before anti-imperialist sentiment around the Vietnam War popularized draft dodging among Black Americans, who were more likely to be drafted. This was incredibly brave, when Black men and women hoped military participation might ease the pressure of Jim Crow and secure equal citizenship, socially if not legally. That outcome of their service never materialized; racist violence awaited returning veterans. As I watched Sun Ra, Isaac Woodard, a World War II veteran attacked in South Carolina by police while still in uniform, came to mind. The heinous attack left Woodard permanently blind. After Blount’s release, now a social pariah, he heads north for Chicago, changing his name to Le Sony’r Ra—and as a musician, Sun Ra. Yet, as the film notes, “It is a mischaracterization to speak of one Sun Ra. At any given time, there was a whole bunch more.”

A lesser filmmaker might have felt compelled to match their protagonist’s experimentalism. Instead, by working in a more conventional documentary form, Turner crystallizes Ra’s mission. He states very clearly, in an interview used as voiceover: “I have to play everything. All emotions that human beings know. And I have to touch the parts of them they don’t know is part of them. That’s my mission: to touch the parts of them they don’t know they have.” Sun Ra achieved this mission through the Arkestra and his commitment to sonic innovation, creating what he called the “alter destiny.” As scholar Louis Chude-Sokei explains in the film: “The alter destiny is a very early articulation of the notion that the future is not only unfixed, but that we are trapped in notions of time that force us in places that we don’t have to actually go. We can step out of time and create another trajectory.”

The word “trajectory” resonates with Ra’s emphasis on lineage. I grew up hearing the adage, “If you don’t know where you come from, how will you know where you’re going?” Knowing where you come from—having that illuminated for you by way of mythmaking, another Sun Ra tenet—matters deeply. His myth creation solidifies Black folks’ legacy as an ever-present people, connecting past, present, and future.

Sun Ra mastered several musical genres—he wasn’t ahead of time, but perfectly timed, and timeless. Big band jazz, doo-wop (as heard in “Dreaming”), and reworked old standards like his rendition of “Over the Rainbow,” a favorite of his, which gained deeper resonance at his keyboards. His influence spans contemporary music and beyond. Early in Sun Ra, a montage spotlights contemporary artists echoing his aesthetic, which predates the term Afrofuturism itself. A segment of the film showcases his work pioneering electronic music. After being introduced to Robert Moog by way of music critic Tam Fiofori, Ra was one of the first musicians to adopt the Minimoog in the late ’60s/early ’70s. By acknowledging his own musical lineage, he time-traveled, mining histories of music, self, and previous civilizations for new sounds and a greater expansion of our mind’s eye by way of what we hear and see. The music is a gateway to true praxis.

Leading by example is integral to Sun Ra’s need to create a better world. One of my favorite anecdotes from the film: he arranged for a promoter to take the Arkestra to Egypt while touring Europe. Archival footage of Sun Ra and his musical family frolicking among the pyramids makes clear his ability to achieve seemingly anything, though bandmates’ stories add humanity to Sun Ra’s mythology. Even interplanetary angels get sleepy! One musician recalled Ra sometimes dozing during hours-long rehearsals. More compellingly, one bandmate describes him as having “a mother’s love,” not easily fitting standard masculinity or sexuality frameworks. His existence embodied a fluid Black futurity.

A beautiful screening moment came afterward when we realized that Marshall Allen sat in the audience. The sharp and quick-moving centenarian leader of the current Arkestra, still performing and fresh from releasing his debut solo album, made perfect sense as an attendee—his father sold Sun Ra the Germantown building for $1 where the band lived and worked, and where I believe Allen still resides, spreading the gospel.

Brittany Shyne’s Seeds evoked the dreaming Africans from Bambara’s quote. Dreams of self-determination required land of actualization. Documentary’s dispatch from Sundance covers the film’s interest in agricultural connections, and how it resonates in the current political context as well as its form. Here at BlackStar, the film joins the stories we’ve come to know, some of us intimately, about Black America’s relationship with dispossession and migration: dashed dreams of 40 acres and a mule; displacement from Southern and urban Black enclaves through white supremacist violence (like the Red Summer of 1919); or legal mechanisms like deed theft or eminent domain. From Brooklyn’s brownstones to California’s stolen beaches to Georgia’s man-made Lake Lanier, which flooded the homes and cemetery of the Black town of Oscarville, and where the supposedly vengeful spirits ensure their legacy through hauntings and drownings. Though Shyne’s film opens with a funeral, it focuses on people who are very much alive—elders who have been tending, tilling, and farming the family land before Shyne (or I) was even a thought.

At times, this film felt dreamlike, in the best way, evoking hours spent sitting on my great-grandmother’s lap under her walnut tree. Shyne’s double duty as cinematographer-director captures intimate relationships with folks whose family land faces diminishing returns. The black-and-white cinematography and quotidian focus of Black life conjured films like Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Seeds’ sound design creates greater intimacy with the farmers’ labor. One of the most moving moments: Willie Head, Jr., showing us around his home, which he is working on to restore to its former glory, holding his mother’s portrait. “Who does she look like?” he asks, ushering his granddaughter closer to the frame. Their resemblance moved me. Head recounts dreaming of his mother before his granddaughter’s birth: “God sent my mother back to me.” Generations passing down ancestral faces is a beautiful inheritance.

Although the main farmers in the film are elders, children populate the frames—darting in and out, riding in the back of pickup trucks, up underneath their meemaws and pop-pops. They are the future, basking in the beauty of their inheritance, the love being poured into them by way of nurturing not only their minds and spirits but also the grass underneath their feet. This film testifies to existence across generations, including those no longer with us, like Ms. Jessie Mae Head. Day by day, I recognize more and more that the moving image offers our closest approximation to time travel.

See you next year, BlackStar.

A live recording of The Daily Jawn, the BlackStar Festival podcast morning show.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Fall 2025 issue.