I was originally drawn to a career in film because of the power of storytelling to influence and inspire. But storytelling, I have since realized, is not limited to any particular medium. From the stories we form about ourselves in childhood to the stories we absorb from our environment, personal narrative is the foundation of our mental health. It impacts the way we view the world and how we imagine its possibilities.

I have spent the majority of my career in film distribution, helping artists tell their stories. I began my career in the studio world but ultimately left to work in social justice, driven by a higher calling to contribute my skills and talents to a larger cause. Hoping to be of even more service to overlooked filmmakers and films, I founded my own consulting practice that focused on supporting socially impactful projects produced by people from marginalized groups. Over time I found it even more meaningful to become my clients’ ally, advocate for offering emotional support, and assuage the unique fears that come with the vulnerability of releasing a creative project. Drawing from my own multilayered childhood adversities, my heart knows the meaning of compassion. Having experienced the life-changing power of therapy myself, I am driven to offer help and support to others, especially those facing anxiety and depression.

According to surveys conducted in June 2020 by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 40 percent of Americans are grappling with at least one mental health condition.

According to surveys conducted in June 2020 by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 40 percent of Americans are grappling with at least one mental health condition. Having spent the last year and a half in quarantine amidst a profound and ongoing threat and grief, it’s reasonable to believe many of us are living with some degree of COVID-related PTSD.

Shortly before the start of the pandemic, The Hollywood Reporter published a feature story addressing mental health in Hollywood and cited an alarming statistic: "According to the CDC, the highest female suicide rate from 2012 to 2015 occurred in the combined fields of arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media." In 2019, the CDC reported that suicide was the second leading cause of death among individuals 10 to 34 years old and the fourth leading cause of death among those 35 to 44 years old (across all genders and industries). Even more distressing was this statistic: "There were nearly two and a half times as many suicides (47,511) in the United States as there were homicides (19,141) in the same year."

Keeping in mind these figures are pre-pandemic, it is clear that there is an underlying problem in our society that is largely being ignored. They say artists reflect the times they live in. As storytellers and creatives, what can we do to bring this issue to the forefront?

Emotional and mental pain are seen as more discreet. It is easier to say, “My head hurts” than, “My heart or spirit is broken.”

Much of the problem lies in the unequal way the United States treats mental health compared with physical illnesses. Emotional and mental pain are seen as more discreet. It is easier to say, "My head hurts" than, "My heart or spirit is broken."

Thanks to the courage of people like Simone Biles, Meghan Markle and Naomi Osaka, mental health is becoming more of a mainstream conversation. It should not be lost on us that Black women are leading the charge here. Our capitalist society is built on valuing productivity over rest. When people, especially women of color, choose themselves, their health and their safety over productivity, we all become a little more free. As Audre Lorde said, "Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare."

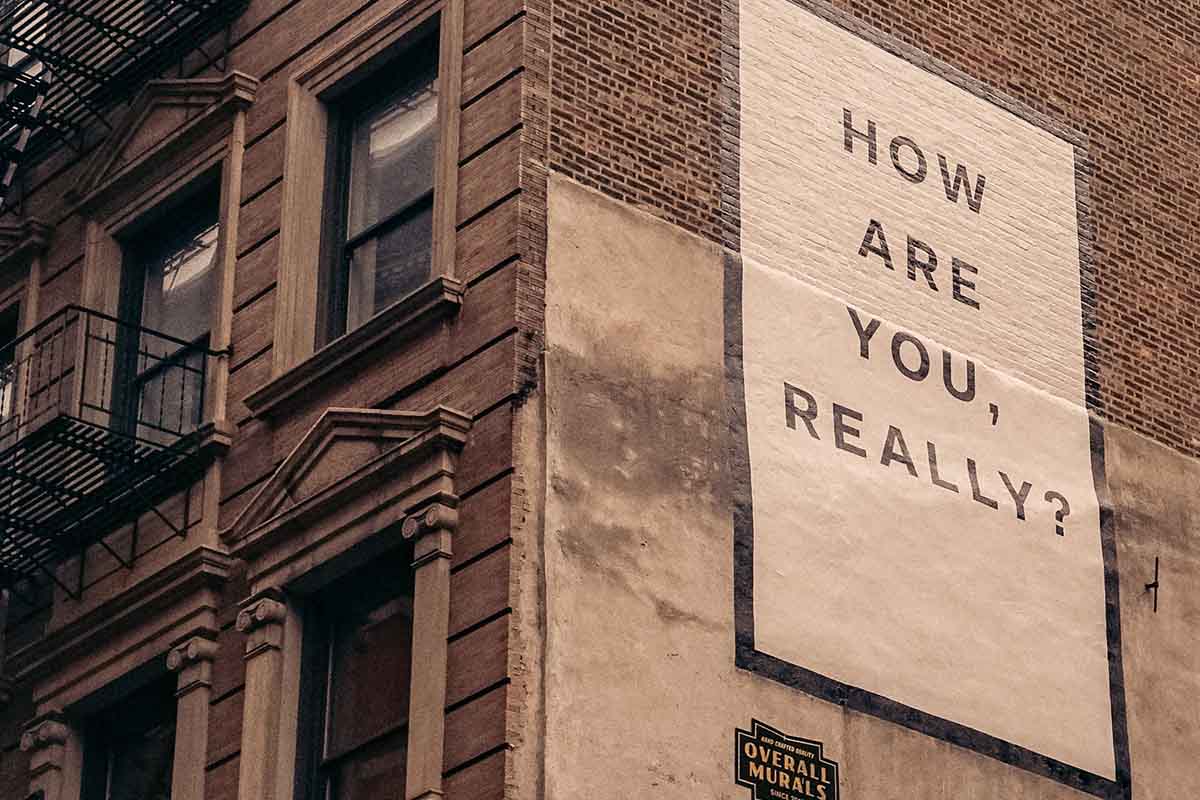

What lessons can be learned from this moment? As offices reopen and entertainment events carry on, how can we begin to create a mind shift when it comes to mental health? Amidst all the calls for changes addressing the industry’s numerous inequities, now seems like the opportune time to include mental health in the infrastructure moving forward.

In Sonya Childress’ must-read piece, "A Reckoning: The Documentary Film Industry Must Chart A New Path Forward," she asserts, "What is lacking are protocols for ethics and accountability across the industry, from filmmaking to artist-service provision. That begins with a full-throated acknowledgement that racial, gender, and class bias are baked into both the artistic form and the industry. From that acknowledgement must come the development of new norms and protocols that represent the diversity of those in the field, and a shift in power and privilege from those who historically held it. Ultimately, new protocols must be built to ensure filmmakers and film institutions do not harm the communities and artists they aim to serve."

The topic of mental health is critical to the documentary field for many reasons. The subject matter of films is often heavy; stories about racial and gender injustices and various environmental, political or societal threats are dispiriting.

The topic of mental health is critical to the documentary field for many reasons. The subject matter of films is often heavy; stories about racial and gender injustices and various environmental, political or societal threats are dispiriting. Documentaries of a personal nature add even another layer of vulnerability. For those of us who have been fortunate enough to work remotely in the last year, the lines between work and home were and are often blurred. Boundaries are remarkably undefined in this industry: long and often unpredictable hours; numerous years on a single project; constantly "being on," from initially garnering funds all the way through promoting the film’s release during festivals and distribution.

Documentary filmmakers also carry an enormous weight of responsibility. In addition to leading their crew, they share a pivotal relationship with the protagonist of the film. They bear witness to intimate moments and are entrusted with authentically capturing and honestly reflecting the story. It's the same skills of empathy and compassion that make a great documentary filmmaker and also leave one susceptible to burnout and fatigue. The workload seems plentiful, but the compensation often does not match up.

This past summer, the Center for Social Media and Impact released their State of the Documentary Field Report, which included key findings of economic issues in the field. Just as COVID-19 continues to affect the BIPOC community disproportionately, so do the persistent inequities facing today’s documentary professionals.

Last summer American Documentary (AmDoc), the nonprofit organization behind the award-winning PBS series POV, launched a new Artist Mental Health Fund to support the BIPOC documentary community. The fund creation was informed by critical learnings shared from the D-Word community and at IDA’s Getting Real 2018 conference, as well as conversations with filmmakers and mental health practitioners. AmDoc decided to mindfully pause and reassess the fund application process after encountering critical conversations within the week of the announcement. "The critiques and feedback stated that it marginalized people to relive trauma; asked artists to trust institutions enough to be vulnerable with their mental health needs; and be evaluated as they compete for funding," says Asad Muhammad, Vice President of Impact and Engagement Strategy at POV. "Every BIPOC director, producer, or interactive creator who applied to the mental health fund before the application was taken down was funded at 100% of the amount requested. As we administered this pilot, one of our guiding principles was to trust people when they tell you what they need especially as it relates to mental health." AmDoc is finalizing its revised plans and hopes to share them in the coming months.

The pilot fund does raise several questions for the documentary community, however: Who are the appropriate parties to administer funds for mental health? Do filmmakers feel comfortable sharing healthcare need information with the same organizations they are pitching for funding?

It is challenging to ask for help, especially if you’re usually the caregiver. What I have found through therapy is the only thing worse than suffering is going through it alone. The last 18 months have shown us the value of community and why now is the time for this discussion. We know the current paradigm can’t continue. While we’re reimagining what is possible, how can film teams protect their time and boundaries in a demanding work culture? The need of the hour is the formation of coalitions that create a shared, industry-wide set of values and practices about mental health in the field.

The Documentary Accountability Working Group is addressing this and more, and they recently unveiled newly organized core values for ethical and accountable nonfiction filmmaking at this year’s BlackStar Film Festival, some of which outlined "the opportunity to prioritize the needs, wellbeing, dignity, and experience of all those associated with your film."

I look forward to the day when it’s not an act of bravery to speak about mental health and when mental health line items are a common occurrence built into project and office budgets. Prioritizing healthy minds and bodies will look different for individuals and organizations. I admire that an influential organization like Doc Society is piloting a four-day workweek. "Our trial four-day workweek just began, but it is requiring of us a total rethink of what we are here to achieve and the best ways to do it," says Jess Search, CEO of Doc Society. "Are we asking the team to do five days’ worth of work in four, or simply work less? We realized that the answer is far more revolutionary."

There’s a lot of gaslighting of normalcy going on right now, but I believe it’s essential to normalize struggling, not being okay, and taking time to rest. Part of what makes great storytelling are the extraordinary moments captured of the human condition. I look forward to a culture that enables us to bring not only the polished parts of ourselves but our whole, true selves reflecting the broad spectrum of the human experience.

Rebecca Sosa is a distribution and impact strategist and passionate mental health advocate. In addition to her consulting company, Empowered Stories, Rebecca is working towards a master’s degree in clinical psychology and licensure as a mental health professional. She hopes to expand mental health literacy and access within the creative and BIPOC communities and destigmatize it across all generations and cultures.