As 'POV' Turns 35, Executive Producer Erika Dilday Speaks about the PBS Nonfiction Showcase

POV, the longest-running showcase of independent documentaries on PBS, turns 35 this year. Its executive producer since May 2021, Erika Dilday, had her hand at the helm of this 35th season. She came to POV from Futuro Media Group, a multimedia journalistic nonprofit committed to telling overlooked stories, where she was CEO. Before that, she was executive director of Maysles Documentary Center. Here she talks about the current season of POV, what her father taught her about diversity, the logistics of scouting for films, and her upcoming keynote address at IDA’s Getting Real 2022 conference.

POV, the longest-running showcase of independent documentaries on PBS, turns 35 this year. Its executive producer since May 2021, Erika Dilday, had her hand at the helm of this 35th season. She came to POV from Futuro Media Group, a multimedia journalistic nonprofit committed to telling overlooked stories, where she was CEO. Before that, she was executive director of Maysles Documentary Center. Here she talks about the current season of POV, what her father taught her about diversity, the logistics of scouting for films, and her upcoming keynote address at IDA’s Getting Real 2022 conference.

DOCUMENTARY: You started with POV in May 2021. Were you more interested in change or continuity?

ERIKA DILDAY: I have to say both because I’m a big fan of Justine Nagan, who was executive director and executive producer before me. I love her taste and judgment in films. But I’m also a different person. I want to help guide a slate that speaks more to me and my strengths.

D: The season opened with Wuhan Wuhan and closes with I Didn’t See You There. What kind of program goals do these choices reflect?

ED: For me, it’s about humanity and being able to see people who are different from you as human beings, feeling empathy and kinship. We aren’t all the same. Everybody has different issues, but we are far more similar than people would like to think. Both of those films show that. With Wuhan Wuhan, we got a note from a viewer who said he’d never felt real sympathy for Chinese people with this crisis until watching this film and realizing that everybody is doing the same thing: Doctors trying to hold it together, families having children, people making choices about how to offer care. Almost everything I’ve seen that addresses the pandemic seems to have coronavirus as more of a character than as the catalyst.

D: Since its start in 1988, POV has greatly expanded the number of international films. Why is this important?

ED: As a nation, we have a myopic view of the rest of the world. International documentaries help a bit with that understanding. In the US, we’re fed a pop-music diet of media. People need to learn to watch things that don’t immediately feel easy to them.

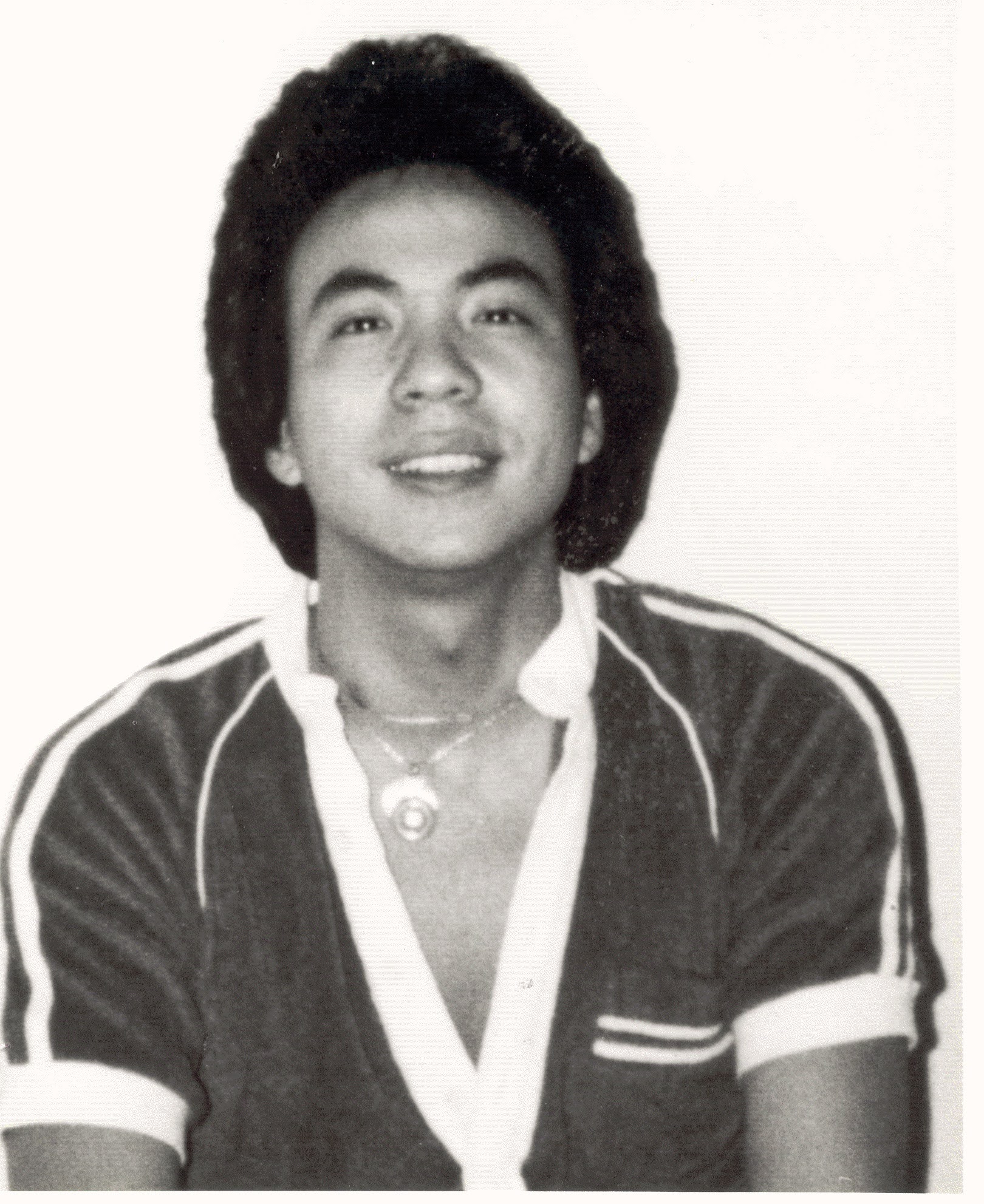

D: The encore presentation of Who Killed Vincent Chin commemorated the 40th anniversary of his murder. Do you plan to show more films from the POV archives in the future?

ED: We would like to. This one, in particular, we wanted to do for a confluence of reasons. One is the 40th anniversary of his death. Number two is that with the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, we wanted to show how long this struggle has been. Three, we’ve got some really celebrated filmmakers: directors Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña, and executive producer Juanita Anderson, who’s on our board. I like having this opportunity to recognize the long body of work they’ve contributed to this industry. They should be household names.

D: Is it important for POV to present films with a point of view, as the name suggests? Because you also show observational documentaries.

ED: To me, everything has a point of view. It’s just whether or not we acknowledge it. I worked at Maysles Documentary Center before this, so I’m certainly interested in that observational category. But even observational film has a point of view. Sometimes you’re seeing someone else’s point of view through the lens of the camera; other times, what the editors choose to put in that film. The only way you’d make an objective film would be to put it in a spinner and just have whatever pops out. Owning that is what gives films credibility. I don’t think you need objectivity; you need credibility.

D: Can you give a preview of your keynote speech at IDA’s Getting Real conference in September?

ED: The main theme is how community is created through building and inclusion, not by canceling and exclusion. In order to create the communities we want, we need to be willing to talk and listen to each other, and work with good intentions. We need to correct each other without it being punitive. We need people not to be afraid to ask questions.

I was recently dealing with a programmer who shall remain nameless, but he comes from a very homogeneous community and said some things that were really offensive. But I also knew this person was completely clueless, so later that day, I sat down and talked with him about the clueless things, during which some more clueless things came up. At first, this person was defensive. But upon realizing that he wasn’t going to be attacked and wanting to do better, we had a great conversation.

D: Season 35 has more than half of its lineup directed by women and two-thirds by people of color. In what ways do these films challenge conventional narratives?

ED: One film that speaks to me is The Last Out. It’s about Cuban baseball players who are trying to make it into the major leagues. But it talks about how many people don’t make it, how they put everything out there, how they sacrifice themselves. The story deals with homelessness, with the inequities in immigration, but it does so from a point of view that we don’t think about it, which is sports and where this dream is coming from.

D: In 1976, your father, William Dilday, became the country’s first Black general manager of a television station [WLBT in Jackson, Mississippi]. Did he change the programming? What did that teach you about the need for diverse gatekeepers?

ED: It taught me a lot. He was my role model in terms of what to do and what not to do. He taught me that anyone who wants to make change does not have the luxury of being comfortable. He taught me to push boundaries. He increased the number of Black people on the staff at WLBT to almost 40 percent, which was unheard of. Even though Mississippi is a state where Black people were 40 percent, they generally weren’t given the chance.

The other thing he did was make decisions that sometimes weren’t popular. There was this awful film called Beulah Land, filmed in Mississippi. Basically, it painted slavery as this happy, benign institution and was nostalgic of the South, and he refused to show it. I still remember the trouble around his refusal and how angry people were. It made me a little nervous, but at the same time I also remember feeling very proud. I learned from him that if you don’t have people who can see things from a different point of view, then you’re not going to change anything. The gatekeeper conversation is a big one.

D: You have a long track record as a producer. Last year, you produced Rachel Boyton’s Civil War (or Who Do We Think We Are?), which deals directly with the question of who gets to tell the story. What did you learn from making that film, and how does it bear on your work as a programmer?

ED: One of the most interesting things about making the film was the discussions that Rachel and I had. She was very open as a director and included me in a lot of her directorial decisions. There were things we would watch, and we’d walk away with just completely different impressions of what had happened. We’d sit there and say, “Oh, well clearly ‘A’ happened,” and I’m like “Oh no, ‘B’ happened.”

As a programmer, it taught me that it’s so, so important to have people in the room who represent not just diverse points of view, but who also have some insight into the communities that you’re looking at. As a programmer, you are a gatekeeper. It’s not just your opinion; it’s making sure that you get the right opinions.

D: Where do you look for films? Do you go to smaller festivals, along with the big guns?

ED: Absolutely. One of my big initiatives is that I would like to start going to smaller regional festivals around the world. I think we do a good job of checking different festivals across the globe. But in the same way if you show up at the New Orleans Film Festival, you’re going to have different filmmakers than you’d have, say, at South by Southwest.

I’m trying to figure out how to get more of them on our radar. Also, I’d like to lend credibility to more of those international regional festivals, so we can help them pull in more people and create gathering spots. Because 50 percent of what I’m interested in is getting more films, and 50 percent is interaction with those communities.

D: How many people are scouting on your behalf?

ED: That’s a fluid number. We’ve got a team in our programming production group of six people, but I’m also looking at expanding it and making it more inclusive.

D: Do you have an open call?

ED: We have an open call on our website, both for POV and America ReFramed [on World Channel], and there’s also a spot for POV Shorts. The call for entries is always open. For the upcoming season, we stop them coming around now. So any films we don’t have yet for Season 36 are more likely to be considered for Season 37.

D: How healthy is public TV in general and what dangers lurk ahead?

ED: Public TV is such an amazing tool. We have a problem in that individuals tend to use it until they are about eight, and then we get them again when they’re about 58. I don’t think it’s because we lack the programming. We lack the ability to communicate well with diverse audiences, with younger audiences, with audiences of color. Cracking that code is what we’re looking for.

For instance, our digital presence could use some work. I just came from Futuro Media, where it was largely Black and Brown audiences in their 30s. We had a terrestrial broadcast, but almost no one who was in that 25-to-45 age group listened to it. They streamed it later. We’ve got to accept that this is the way content is consumed. We found that a lot of younger folks didn’t want more than 20 minutes of content at a time. That’s another reason why we’re growing our shorts.

D: Is it hard to compete for acquisitions against streaming services like Netflix and Amazon?

ED: That’s a resounding yes. But the care and feeding we give to individual documentaries are often attractive to filmmakers. To their detriment, most people who make documentaries didn’t get into it for the money, so often they’re willing to work with broadcasters like us who may not have as much money, but who really want to see the film do what the filmmaker intended. For us, success is when the film is reaching the audiences that the filmmakers wanted and also is being used or referenced in a variety of different ways. It’s not just about, Did it gain us more subscribers? or, How many times was it downloaded?

D: What are your hopes and goals for the future of the series?

ED: I’d like us to have a longer season and more international films, to increase our engagement and our ability to help filmmakers within the industry. I want us to be a responsible documentary film citizen.

Patricia Thomson is a longtime film journalist and a contributing writer for American Cinematographer.