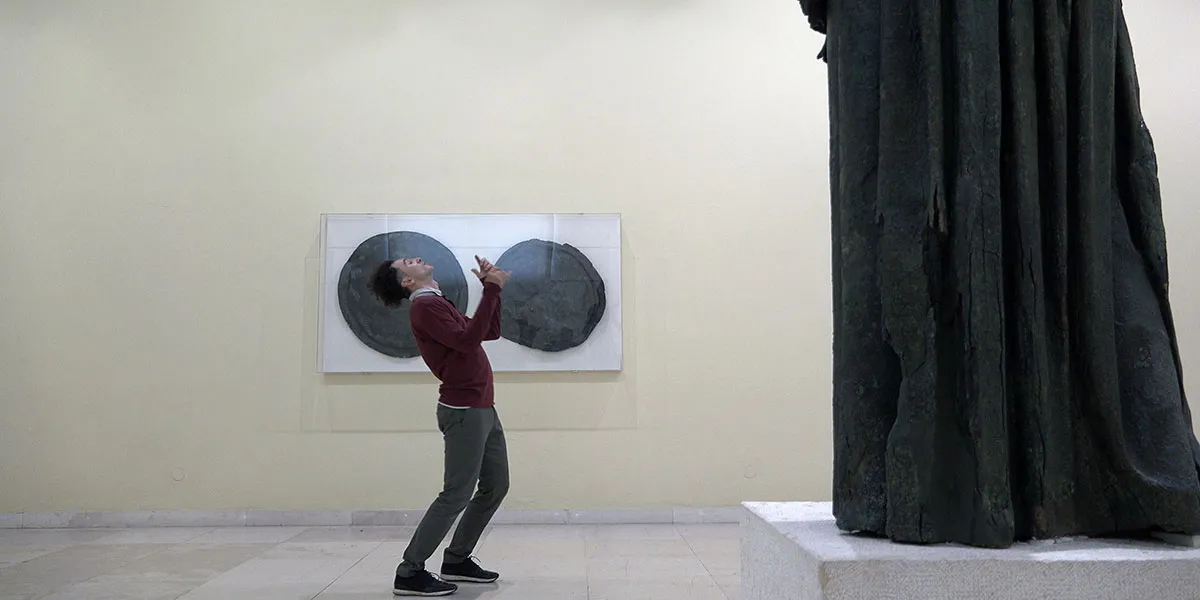

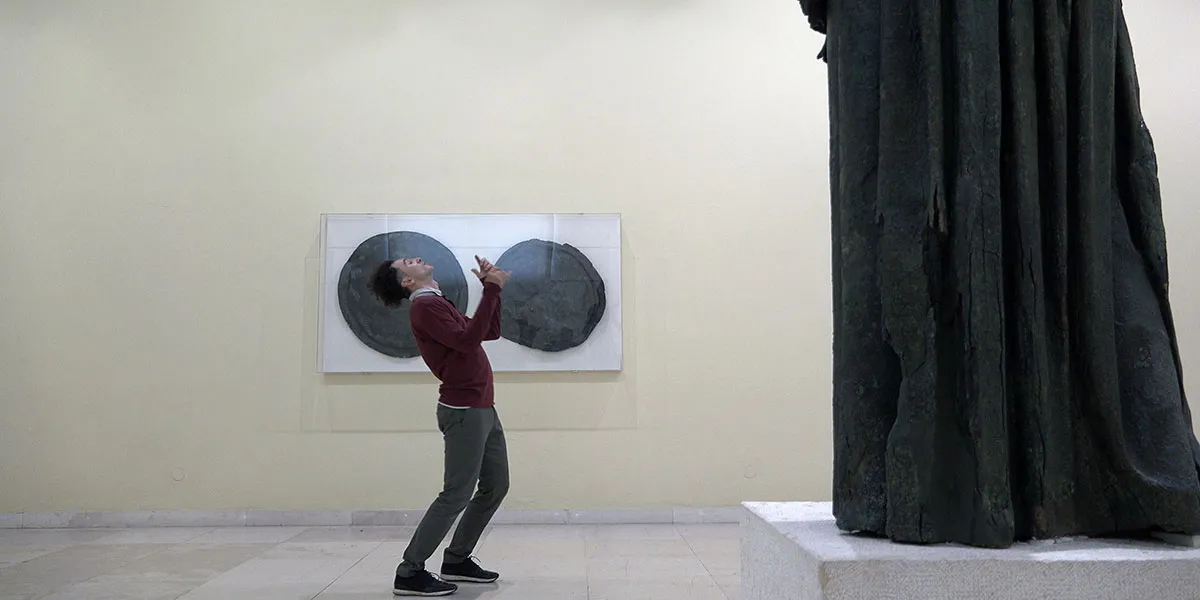

Exergue – on documenta 14. Courtesy of TIFF

Before every screening at TIFF, a trailer from this year’s presenting sponsor teased that the festival awakens the inner film critics of Toronto residents. “It perfectly encapsulated the western-horror-docu-science-fiction-genre,” a school crossing guard declares, raised stop sign in hand. Seconds later, a sports broadcaster offhandedly remarks to her coworker that a film could be classified as “more of a docu-fiction hybrid.” Among these observations, too, were comments from restaurant patrons and construction workers about confusing eyelines, the pleasure of enduring a 14-hour-long film, and the works of Catherine Breillat. The commercial, from a telecommunications giant, of all corporations, seemed to register the trends and figures beloved by arthouse connoisseurs.

We might glean, then, from the repeated mentions of hybrid films that the merging of documentary and narrative fiction traditions is currently enjoying a moment in the spotlight. But despite the attention paid to this particular genre, TIFF Docs, which aims to showcase “the best non-fiction cinema from around the world,” hybrid films were surprisingly absent among its 22 selections. Year after year, the festival section devoted to documentaries tends to be populated by glossy, formally conventional, commercial fare—occasionally punctuated by works from prolific documentarians and festival award winners. Nonfiction works marked by innovation and ambition are pushed to the periphery, a consistent gesture that betrays what the festival regards as “best” in the arena of nonfiction cinema.

Here and elsewhere, I couldn’t help but feel the subtle repositioning of the festival in anticipation of the impending launch of TIFF’s official market in 2026. Intended as a North American counterpart to Marche du Film at Cannes and the European Film Market at Berlinale, these expansion plans impressed upon me the festival’s intention to prioritize sales, revenue, financing deals, and business activity—perhaps at the expense of creative freedom, experimentation, and innovation. I could already see the signs: films often bore the descriptor of “content” or “IP”; one conference speaker appealed to financial logic to address diversity and inclusion, noting that Hollywood forfeits billions of dollars annually due to unaddressed racial inequities; media releases readily identified sales titles in programming announcements. While none of these actions individually justify cause for alarm, I’m wary of what this shift might indicate about next year’s curatorial vision, budget allocation, and the industry at large.

To give credit where it’s due, TIFF Docs demonstrates a commitment to bringing urgent, timely films informed by pressing current events to Toronto audiences. Organized by Palestinian filmmaker Rashid Masharawi, From Ground Zero assembles a collection of 22 shorts from artists in Gaza that testify to the conditions of the ongoing genocide through varied forms and genres. No Other Land, a collaboration between Basel Adra, Yuval Abraham, Hamdan Ballal, and Rachel Szor, and its chronicle of Adra’s enduring fight against the brutal expulsion of West Bank villagers by the Israeli military, are addressed in this issue’s cover feature. In Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, Raoul Peck explores the life of the late South African photographer and activist whose 1976 book House of Bondage, which exposed the violence of apartheid to the world, sent him into exile—a stirring reminder of the importance of bearing witness, documenting, and attesting through images.

Still, invitations to seek hidden, artistically driven gems, to interrogate the collapsing of boundaries between fiction and nonfiction remained open across other programs such as Wavelengths and Centrepiece.

In the playful, enigmatic Lázaro at Night, Nicolás Pereda examines the creative, professional, and romantic tensions that arise when three friends contend for the same role in a film while ensnared in a love triangle. Played by actors of the same names, Lázaro, Luisa, and Francisco navigate strange, often absurd predicaments in varied configurations that reveal their idiosyncrasies, artistic ambitions, and eternal desires to one another. The film doesn’t flaunt its hybrid qualities in any traditional sense, but it would be imprecise to overlook the autobiographical details woven into the characters or the themes concerning performance and naturalism carried out by members of the Mexican theatre collective Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol. Miguel Gomes’s Grand Tour, a black-and-white 20th-century expedition, leans more heavily upon the fictitious conceit of a British diplomat traversing across colonial Asia to evade his fiancée, but the feverish travelogue filmed on a soundstage collides, at times, with verité footage of present-day landscapes from Myanmar, China, and Vietnam.

Bridging modes of the essay and the biopic, The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire is a meditative, dreamlike film that considers the legacy of the Martinican writer and activist by means of a character readying to portray the eponymous figure. Between performing on set and reciting lines from the essay collection Le Grand Camouflage, we gather evidence of the actor’s other, newer role as a mother, a helpful layer for imagining how caregiving duties figured into Césaire’s productive life as an artist. Though the framing device is an invention of filmmaker and visual artist Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich, this strategy closely resembles the real-life feeling of discovering a person through their written works, and of realizing their unknowability despite our best attempts.

In her latest effort to excavate the histories of her artistically gifted ancestors, filmmaker Sofia Bohdanowicz stages a séance that takes the shape of Measures for a Funeral to resurrect Canadian violin prodigy Kathleen Parlow, who mentored her grandfather. Long-time collaborator Deragh Campbell reprises her role as Audrey Benac, a recurring figure who uncovers family histories across Bohdanowicz’s filmography. Here, Audrey is incarnated as a Ph.D. student intent on learning more about the musician after finding a lost concerto dedicated to Parlow in university archives. In the film, Benac’s research on Opus 28 sends her to Toronto, London, and Oslo, locations that Bohdanowicz herself visited after the discovery of the composition by librarians at the University of Toronto. Bohdanowicz sensitively draws out the ability of sound to haunt, lure, reverberate through time, and serve as a vessel for memory, mapping out these ideas onto a detective story that generously holds personal biography and fiction.

But “hybrid” doesn’t quite capture the spirit of these films, despite the term’s aim to contain varying degrees of reality, operating as a catch-all for anything that defies neat classification. It’s often deployed in reference to documentaries with fictional sequences, reenactments, and dreamscapes, but the qualifier is less commonly wielded for films organized by the logic of narrative fiction while incorporating nonactors and unstaged scenarios. We could perhaps find potential in “docufiction,” recalling a tradition found at the origins of documentary, which feels more descriptive, malleable, and ambidextrous. Or, to borrow language from the literary sphere, “creative nonfiction,” which remains capacious and summons John Grierson’s definition of documentary as the “creative treatment of actuality.”

As I contemplated how best to telegraph the blurring of fiction and nonfiction, I began to grow suspicious of the motivations behind pinning down these elusive, shape-shifting films with shorthand. In practice, these terms offer legibility to festival programmers sifting through submissions and drafting curatorial notes, to commissioners and broadcasters receiving pitches, and to distributors designing targeted marketing campaigns. Of its use to filmmakers and audiences, I’m not entirely convinced that an economy of words accomplishes the task of conveying the slippery nature of reality and myth in storytelling with efficiency or accuracy. The truth in Pereda’s beguiling tale vastly differs from the truth in Bohdanowicz’s dramatization of familial history, despite their similar approaches to actor-character boundaries. This language, while convenient at times on grant applications or poster taglines, primarily serves investors and decision makers who principally seek to flatten and streamline as a replacement for understanding and transmitting a film’s complexities.

In addition to films that troubled the confines of the documentary genre, audiences who closely surveyed festival offerings also located formally daring works that firmly resided within the bounds of nonfiction. You might’ve found Collective Monologue, a modern bestiary that locates its subjects in zoos and sanctuaries across Buenos Aires. With critical attention to social and spatial relationships, Jessica Sarah Rinland observes the exquisite creatures inhabiting these spaces, training her camera on their interactions with humans, architectural features, and each other. Intimate close-up shots disorient and mesmerize—tortoises seem to crawl at a glacial pace, a pink flurry of movement reveals itself as a flamboyance of flamingos—deconstructing any notions of hierarchy between animals and zookeepers where scale is concerned. A tender interspecies portrait, the film recalls the rigor of Frederick Wiseman’s institutional studies while affording a uniquely tactile, sensorial experience on 16mm that engages sight, sound, touch, and smell.

After the separate world premieres of Youth (Hard Times) and Youth (Homecoming) at Locarno and Venice, TIFF secured both final entries to Wang Bing’s trilogy following young migrant workers in the garment industry in Zhili between 2014 and 2019. Where the first film, Youth (Spring), attends to the personal trials and tribulations of individuals, the second and third broaden the scope of reference to examine their relationships with the local economy and their distant homelands. Upon completing nearly four hours of witnessing textile laborers ranging from their late teens to their mid-20s navigate workplace tensions, bureaucracy, wage theft, and exploitation in Hard Times, we’re granted relief from these punishing conditions with a sojourn to the province of Anhui for New Year rituals and wedding ceremonies in Homecoming. These are the families, friends, and sweeping rural landscapes traded for long hours, great distances, and the prospect of earning pennies per garment in dimly lit workshops. Originally intended as a single 10-hour film, Wang neatly cleaves the epic into distinct chapters that expand in breadth, presenting an exhaustive patchwork of the Chinese garment trade.

Despite operating strictly in the observational mode, the pair of films curiously occupied slots in Wavelengths and were tagged under Luminaries, a subsection presenting “the latest from the world’s most influential art-house filmmakers.” What considerations or forces seem to be directing this contrived taxonomy of festival programming, where commercial appeal and auteur status appear to compete? Certainly, the duration of the works might be an argument for their inclusion in a section generally attended for its challenging, experimental fare, though an ambitious runtime didn’t seem to be an issue last year for Alex Gibney’s 219-minute In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon, which landed in Special Presentations, or Wiseman’s 240-minute Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros, in TIFF Docs.

The highlight of the festival was exergue – on documenta 14, Dimitris Athiridis’s 14-hour, sprawling documentary on the preparation leading up to the 2017 edition of Documenta, a prestigious international exhibition for contemporary art held in Kassel and, for the first time, Athens. For three consecutive days, I returned to a 45-seat theatre, where I was transfixed by the 14 episodes depicting studio visits, curatorial meetings, and budgetary negotiations led by that edition’s artistic director Adam Szymczyk. Each installment grants a glimpse of the contradictions and inconsistencies between internal values and funding sources that exist at institutions of this magnitude, holding a mirror to the discourse that has circled TIFF’s sponsorship ties to the Royal Bank of Canada—an investor in pipeline projects across Indigenous land and weapons companies arming Israel—since 2023. An endlessly watchable character study, exergue offers unprecedented access to the labor required to mount the quinquennial showcase, unveiling the tedious administrative and economic demands required to support artistic expression.

I should admit that I slipped out of the screening on the second day for a brief excursion to see Dahomey, this year’s winner of the Golden Bear at Berlinale. In the follow-up to her 2019 feature debut Atlantique, Mati Diop reinvests in the spectral realm to trace the repatriation of 26 royal treasures from France to the present-day Republic of Benin. Should the restoration of 26 items out of an estimated 7,000 be celebrated? Or troubled, given the timeline that can be extrapolated from this overdue homecoming? How should royal treasures be displayed, and to whom? Pressed between several hours of exergue on either side, Dahomey lends subjectivity to that which is exhibited, a captivating counterpart to a portrait of those holding the power to exhibit.

Despite TIFF’s market-oriented shift, my search for nonfiction films that held high ambitions and ventured beyond the strict conventions of documentary proved successful. And I suspect I’m not alone. I encountered the same friendly faces at several screenings, friends waiting in a rush line for a program of avant-garde films, fans swarming Wang Bing for photos and autographs after a Q&A, and a room of indefatigable attendees who consumed in three sittings what Dimitris Athiridis envisioned for a streaming platform. In a media landscape fueled by mass appeal, this festival experience served as an affirming reminder of the communities of filmmakers and audiences who carve out their own spaces, embracing the strange and esoteric, and resisting mainstream pressures to fold and follow.

This piece was first published in the Winter 2024/2025 print issue of Documentary.

Winnie Wang is a writer and programmer based in Toronto.