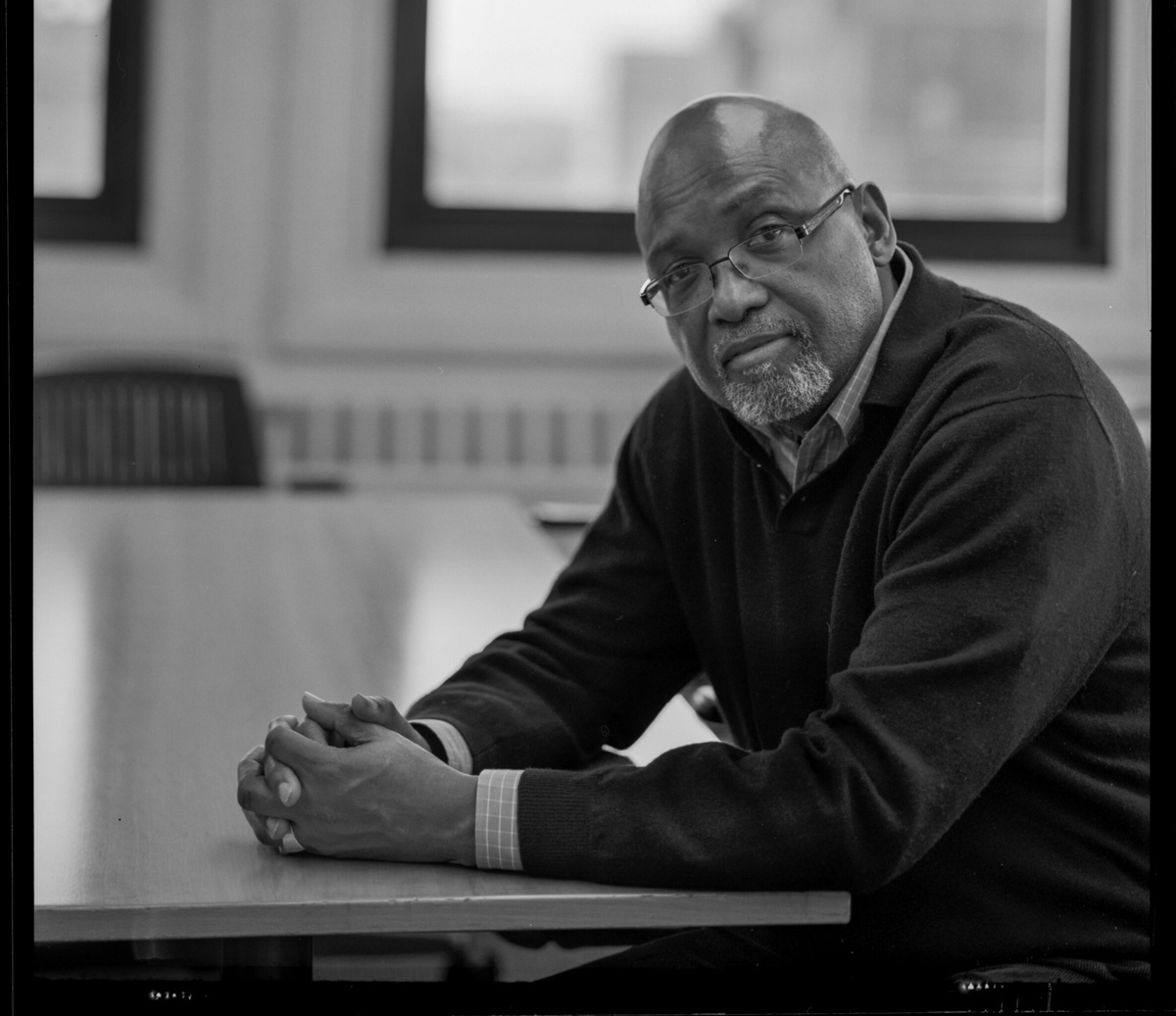

IDA Career Achievement Award: Sam Pollard, Chronicler of the African American Experience

By Tracie Lewis

Sam Pollard has spent the last four decades crafting stories primarily detailing the African American experience—stories that reveal complex protagonists (Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta be Me), examine a system of exploitation and racial oppression (Slavery by Another Name), and bring to the forefront conversations on racial injustice on children of color by law enforcement (The Talk: Race in America). The Harlem native’s impressive oeuvre boasts a cross-pollination of nonfiction and fiction, historical events and contemporary issues, and portraits of entertainers and politicians.

The multi-hyphenate editor-producer-director-writer, the 2020 IDA Career Achievement Award honoree, received IDA’s Avid Excellence in Editing Award in 2008 and won a 2003 IDA Documentary Award for Best Limited Series for The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, which he produced with Bill Jersey and Richard Wormser. This year, Pollard’s film MLK/FBI is nominated for three IDA Documentary Awards: Best Feature, Best Director and ABC News VideoSource Award for best use of footage. In addition, the series Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered, for which he co-directed two episodes and is credited as executive producer, is nominated for Best Multi-Part Documentary.

Pollard is an Emmy Award winner for Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming for By the People: The Election of Barack Obama and an Emmy nominee for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction special for Sinatra: All or Nothing at All.

Pollard was editor on five of director Spike Lee’s narrative films, as well as four of his documentaries, including the Oscar-nominated 4 Little Girls, the IDA Documentary Award and Emmy Award-winning When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts about the tragic effects of Hurricane Katrina, and its sequel, the Emmy-nominated If God Is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise.

Documentary spoke with Pollard about the origins of his career, the filmmaking process, collaboration, work-life balance, wisdom, gratitude, and dedicating time to mentor and teach.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: Can you describe those early days participating in the film and television workshop at WNET in 1971 and 1972?

SAM POLLARD: I was learning the film business. There were about 15 of us who were brought into this program to learn how to make films, documentaries. We learned how to shoot, edit, tape sound and produce. We were all students. We went two nights a week at a studio that belonged to a well-known photographer, Chuck Stewart, and professionals came in each week to teach us the fundamentals of making films. Then, we’d go off and shoot little films, then edit and screen for the executive director. We made three short films. We made one black-and-white without sound, one black-and-white with sound, and then the final film was a color film with sound. With each film we had a particular position. I was an AC [assistant camera] and the editor on the first film. That’s how I got introduced to editing, and then I was the editor for the second and third film, that’s when I realized I wanted to be an editor.

D: What skills did you develop during that time that you carry with you?

SP: The one skill that I had was the passion of being an editor. That’s the thing that attracted me. I was terrified of being on location. I was a terrible AC. I didn’t feel comfortable around people; I was very shy back then. The only place I found solace and solitude was in the editing room, where it was dark. Nobody could see me make mistakes. If I made a mistake, I could rectify by putting the pieces back together. That’s where I felt most secure. So, when I got out of the program in ’72, I was working at a marketing firm in midtown, on 33rd Street and Park Avenue, and one day my mother called and said that this production manager called and they got names from the people from the workshop. He was the production manager on this feature film, Ganja and Hess, directed by Bill Gunn, and they were looking for an apprentice editor and they got my name from the workshop. I had an interview with the editor, Victor Kanefsky, and he became one of my main mentors. He hired me, and that was the beginning.

D: How did working as a producer/director on the acclaimed Eyes on the Prize II series at Blackside Productions have an impact on your career? What did you learn from that experience?

SP: I learned that I had a big mouth and that I should learn before I spoke. I was 37 years old and I’ve been editing basically since I was 25. I had been an assistant for three years and then I was an editor from 25 to 36. Like a lot of New York editors in particular, I had a lot of ego and I thought I could do a better job than a lot of the directors I was working for. When Henry Hampton [filmmaker and founder of Blackside Productions] offered me the opportunity to be one of the producers/directors on Eyes on the Prize II, I had a rude awakening and I learned that it wasn’t so easy—to do the interview, what kinds of questions to ask, what kind of subjects to pick, how to craft the story on paper before you went into the editing room. I found out it was really hard being a producer and director. Initially, I was not only going to be a producer and director, I was also going to edit on the show. On the first show I failed miserably at all three. Henry said if Sheila and I didn’t do a better job on the second cut, he was going to fire both of us. So, I had to make a momentous decision: decide if I was just an editor and didn’t have what it takes to be a producer/director. I had the weekend to make a decision. When I returned to Blackside after that weekend, I asked Henry if our show could afford to hire an editor and he said yes. I knew what I wanted to do, be a producer/director and not edit anymore. So, I took that big leap; I had to prove to myself I was good enough to step into the director's chair.

D: Then you circle back and in the last ten years or so you’re a producer/director again. Why transition back to producing and directing?

SP: I’m now in the fourth decade of my career; the trajectory was even after I produced and directed the Eyes on the Prize II, I went back and I started to edit feature films for Spike [Lee] for almost 10 years, off and on between editing docs for Spike, 4 Little Girls and When the Levees Broke. Every once in a while I’d get a directing gig. By 2000, I was getting more offers to direct, and I think a lot of it comes from just experience and feeling a kind of maturity that I could do it. I could make films as a director and producer. Part of it comes from my understanding about how to make films in the editing room. So, I’ve translated some of that thinking from that experience to when I shoot films. For the last four or five years now, I don’t feel like I need to edit. I can make films without going to the editing room because I know how to think about how to make the film. I am more comfortable. I’m also more seasoned. And it’s not to say that I think I’m brilliant and I don’t make mistakes; I still make mistakes, but that’s part of the process.

D: You credit Victor Kanefsky, George Bowers and St. Clair Bourne often as your mentors. One of your former students referred to you as always being available and accessible. What value do you receive from generously dedicating time for mentoring up-and-coming filmmakers?

SP: The value is simply this: to see somebody else’s career blossom, grow and mature into filmmaking is a wonderful experience. One of the reasons I love being a teacher is to interact with young people, to see how young people think, to see how they make films, to see how they see the world, and then to have an opportunity to help someone get a step up in their career. That’s the same thing that happened to me. If I hadn’t had a Victor, if I hadn’t had a George Bowers or I hadn’t had a St. Clair Bourne, I wouldn’t be talking to you today. Every one of those human beings gave me something to help shape my level of confidence and my belief in myself, and that is an important thing to have. And the confidence to know that even when you fail, it’s not the end of the world.

D: Like Spike Lee and Martin Scorsese, you teach at New York University [NYU], and you’ve taught editing courses there for 26 years. What inspired you to become a professor?

SP: Victor Kanefsky inspired me to become a professor because if it wasn’t for Victor Kanefsky sitting with me a couple of times a week from the age of 22 to 25, I wouldn’t be an editor, I wouldn’t be a producer/director. His mentorship, his ability to sometimes articulate and sometimes in an inarticulate way explain to me the craft of making films through editing is what really cemented my attitude that I could be a filmmaker. First, that I could be a film editor and then I could be a filmmaker. I owe a lot to this man. He nurtured and supported me, and chastised me. He helped me really shape my career.

D: You made a seamless transition from being an editor to director. What skills would you consider the most important for making the transition?

SP: The two most important skills are listening and paying attention. Sometimes you don’t want to listen to anybody with feedback, but you do and then you can pay attention. Those are very important when you are making films—particularly if you’re editing and particularly when you’re directing. Sometimes the communication doesn’t work, sometimes you can figure out how to make it work better.

D: People refer to you as Spike Lee’s longtime editor; how do you feel about having that label?

SP: Initially my reaction was, I had a career before Spike Lee and I have a career after Spike Lee, so I was really put off by it. But then, after Clockers, I embraced it. Obviously it’s a connection; he’s a great film director.

D: What did you learn from Spike?

SP: Sometimes you have to think outside the box about how you want to visualize stories. He always takes chances. And that, I respect tremendously. Sometimes I come up with ways to shoot a scene that in the old days I would have probably taken the safe route, and sometimes I’ll take the more adventurous route because I’ve seen Spike do it.

D: It’s not uncommon for you to work on multiple projects at a time, and even have a couple of films come out a year. How would you describe your work life, professor life and personal life balance?

SP: I’ve been fortunate that I’ve had a wonderful wife [Joyce Vaughn] who supported me. Sometimes she would say, You do too much, but she’s always been there for me when I was dealing with multiple jobs, trying to deal with my family, take the family on vacation, trying to be as good a parent as possible. She’s a wonderful mother and parent and a great spouse.

And also, I love to take on lots of stuff. I have a big appetite. So, this appetite meant that I just didn’t want to do one show. I wanted to do two films, I wanted to consult on a couple of films, I want to help students. I developed an appetite as a freelancer because I understood, in the early part of my career, you could not wait to finish a job to find another job, you just couldn’t do that—that would be crazy. So, I was always looking for work, even when I was in the middle or near the end of the job.

I wouldn’t try to edit two films at once because that’s impossible, but I could consult on somebody else’s film. And, then I became a teacher.

The other thing I would say is the multitasking that I do, I got from working for Victor at Valkhn Films, his company, because we would do a documentary, we would do an industrial and we’d do them all at the same time. We’d jump from one film to the other.

D: You directed the film Slavery by Another Name, based on a book of the same title by Douglas Blackmon. When using a book as a main source, how do you distinguish the most interesting aspects of the book to include in the film?

SP: Doug’s book is over 300 pages. So, we had to figure out what was important. We hired a writer and with the executive producers to go through the book and highlight what we thought was the most compelling. We had to make the decisions of what we thought would work effectively as cinema. The sections we pulled we felt were the best ones that would translate and make into a film.

D: Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered and The Talk: Race in America are documentary series that involve sensitive subject matters. Talk about the interview process when doing these types of films.

SP: As a director you want to be sensitive to the answers and the questions you want to ask. With the Atlanta story, we were talking to the families that had lost loved ones. So we wanted to be very sensitive about the kind of questions we asked. We didn’t want to exploit them. We wanted to try and have them go back and relive those moments, which was sometimes horrific. But we did not want to do it in a way which is what I call a “got you” way or in an exploitive way.

The Talk is different. It is important whether we live the experience or not to understand that in America, systemic racism exists every day. It doesn’t matter if you are a Black man in your 20s, 30s, 40s; you can be a Black mother with children; you can still face these issues of racism in America. Our job was to make sure you’ve done the research on the people you are going to interview. To be sensitive to what they had gone through—to understand that. To me the job is always to be respectful. You have to go in there caring about how they are.

D: You were a producer and editor on Sinatra: All or Nothing at All. How do you manage to give deeper insight to an iconic person that already has a large public presence, using primarily archival interviews?

SP: Alex Gibney, the director, had a very smart idea of using the concert Sinatra had done before his retirement as a frame to tell the story. Through Sinatra’s music, he showed the arc of his career. The second important thing we got was from the family. Tina Sinatra had done audio tapes, because she was going to do a movie about Sinatra. She got him to sit down and recall on audio what his whole life was like—growing up in Hoboken, making it big in Hollywood, his first marriage, the struggles he had, his second marriage with Ava Gardener, the re-flourishing of his career with From Here to Eternity, becoming a big movie star, and his marriage to and divorce from Mia Farrow. What I brought to this project, quite honestly, was really a deep affection for Frank Sinatra. I grew up watching this guy in all of these movies. Listening to his music. I loved the movies. I loved the music. And I loved the fact that he was a very complicated guy. Part of my job was to make sure that that all came through.

D: How do you determine the narrative for the story when directing documentaries about iconic people that are part of our history, like Marvin Gaye, Zora Neale Hurston, August Wilson, Sammy Davis Jr. and recently, Martin Luther King Jr.?

SP: In some cases, it’s truly developing a narrative after you have sorted out all of your interviews, gone through your transcripts and build out the narrative from your transcripts. I would say that was the case with the Zora Neale Hurston film, that was the case with the August Wilson documentary, that was the case with Marvin Gaye. Now, with Sammy Davis, I came on that project as a second director. There was a script already—that was something very unusual. When we started to build the film, we built the film from the script even though we made massive changes in it. We had a template already.

D: Looking back at the Black Journal days [the public television series that ran from 1968 to 1977] when staffers walked out and Al Perlmutter, a white producer was replaced by Black filmmaker William Greaves. Today, filmmakers of color are speaking out to tell their own stories. What are your thoughts about what has changed, then versus now?

SP: I wasn’t working in the business then, but I know the story from St. Clair Bourne. The change is the big corporations—HBO, Showtime, Netflix. They didn’t exist then, but they now see—and it’s all coming out with the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor—that Americans have reached a reckoning, that you’ve got to open these doors to bring in more people of color to make films and to tell our stories.

The other big change is that there’s more voices now from the communities of color than when Saint and I were coming up. It was always the same attitude; we want to tell our stories. That’s one of the things that St. Clair Bourne imprinted in me when I got to meet him in 1980. I had been in the business eight years by that time, and had just returned from California editing a feature film for George Bowers and George had recommended me to edit a film for St. Clair titled Chicago Blues. I spent six months in the editing room with Saint and we talked about the importance of us as filmmakers of color telling our story. It’s the same philosophy today. There’s just more filmmakers of color out there that want to tell our stories than when Saint and I were coming up.

D: What projects would you like to do, but haven’t done yet?

SP: I’ve got my passion project on Max Roach [jazz drummer], with American Masters. That’s my baby I’ve been nurturing since 1988. So, finally it’s going to see the light of day, hopefully.

D: What three key points of advice do you prescribe for beginning filmmakers to have a lasting career in this industry?

Be tenacious, be patient and be respectful.

Tracie Lewis writes, is directing a documentary and teaches the history of American film and world cinemas at Chaffey College.