“Really… I feel reluctant… coming to receive you… as my interviewers or crew… Because ever since my exposure to the camera…. As an internationally acclaimed poet… nothing much has come my way… Despite repeated interviews and exposure to the camera… So, in other words… I’ve become allergic to the camera!”

Harrison Cudjoe enters the frame of the 1997 documentary YCP 1997 with these words, which have resonated with Indian documentary filmmakers, Anjali Monteiro and K.P. Jayasankar. Over nearly three decades of documentary filmmaking, they—like scores of filmmakers who spend months and sometimes years probing a single question and navigating more questions masquerading as answers—have found themselves going beyond the narrative they have created, continuing to be significantly invested in their protagonists and their lives. But when films explore various forms of conflict—and various forms of prisons, as Cudjoe had put it—to what extent can filmmaking as a process continue after the camera has been turned off?

Beyond the temporality of the filmmaking process—and the possibilities it enables in the continued process of bearing witness—documentary filmmaking allows for the format to explore questions of and from both sides of the camera. Monteiro and Jayasankar found themselves delving into this way back in 1996, with their documentary Kahankar: Ahankar, which attempted to bring together two disparate discourses: a selection of stories and paintings of the indigenous Warli community from western India, as well as the writings that have contributed to creating mythologies about them. The filmmaker duo were already in touch with a grassroots organization that had been working with the Warli community, and through the documentary, wanted to critique the position of authority. “The narratives and paintings by the Warlis address their history and their own worldview; whereas in the documentary, we have punctuated this with narratives by anthropologists that paint them as primitive people. It is not just about our relationship [with the people featured in the film], but about reading between the indices of the stories and narratives about them,” Monteiro explains, adding that they did not simply want to be paratrooping into their space. The result, according to Monteiro, is a film about narrativity and the role of the filmmaker, rather than a film about the people.

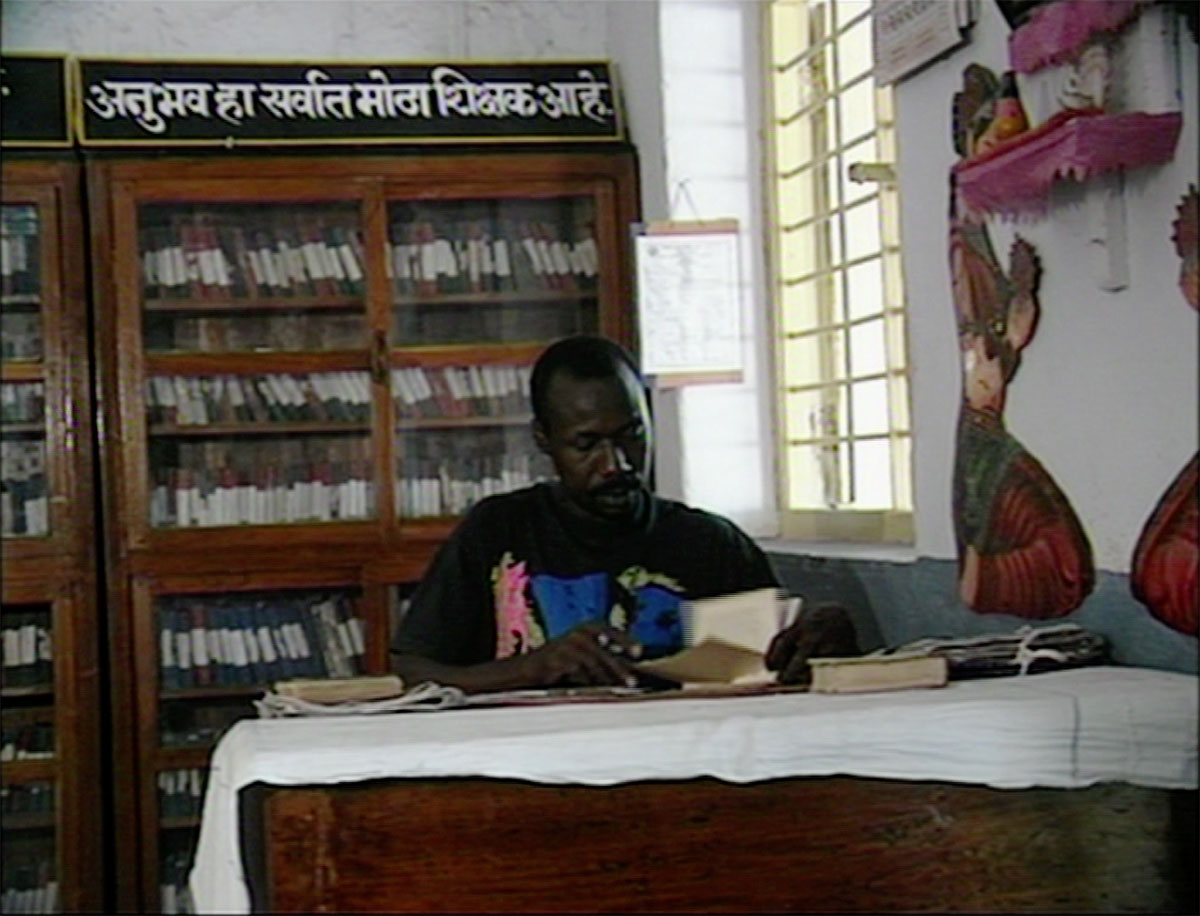

YCP 1997 explored the lives of six poets incarcerated in India’s Yerwada Central Prison. Instead of focusing on the prison experience, the filmmakers’ relationship with the film’s protagonists was like “one set of creative people who were interacting with another set of creative people, to understand the experience of the prison, and how that brings forth poetry or other creative forms, through that suffering, pain and shock of change of one’s status,” Monteiro says. It was for this reason that the “crime” of the poets—the prisoners—is not mentioned in the 43-minute documentary, unless it was related to the poetry in a tangential manner. “We did not want to once again put on display the hierarchy of judgment, in identifying a person as a murderer or thief,” Jayasankar maintains. “If I am being interviewed, I would like to be called ‘filmmaker and academic,’ not ‘Jayasankar, the traffic offender or digital pirate.’ We have all violated laws; we have just not been caught.”

The whiff of the nature of the relationship between the filmmaker and their film’s protagonist becomes evident within the first few frames of any documentary film. Monteiro explains that at an immediate level, it falls upon how the filmmaker relates to the people in the filmmaking process, after the film is made, and the way a relationship might be maintained thereafter. “But the relationship has to be also dealt with within the text of the film, so that they don’t just remain your questions. We want to infest the minds of the viewers with these [questions], making them uncomfortable, and not simply convey the quaintness of the stories of our protagonists. All of us are implicated in the kind of life we continue to lead…. what we choose to look at or what we choose to ignore.” Towards this end, the filmmaking couple have been adhering to—and imparting their students with—the “ethical norm” of screening the film for the people in them first, before going public. They have deleted bits that a film’s protagonists have been uncomfortable with. “These days, filmmakers take verbal, written or recorded-on-camera consent,” Monteiro explains. “That becomes very tokenistic, because people often don’t understand what they are giving their consent to. So we feel it is important for the protagonists to see the final edit.”

That both filmmakers have been able to stay in close contact with Harrison Cudjoe, one of the featured poets in YCP 1997, is beyond implicit dignity towards the subjects of the film, let alone about using the camera in a predatory manner. After watching the film at a special screening organized by the prison authorities. Cudjoe—who had been in prison since 1986 on a drug possession case—asked Jayasankar for help with a lawyer. Jayasankar reached out to his connections, and eventually, Cudjoe was acquitted in 1998, a year after the release of the film. “He thereafter called us his foster parents,” Jayasankar recalls. “He said he was glad he had decided to give us the interview for the film, or else, he felt, he would still be languishing in prison. What we did was actually very little. Wherever possible, we do what we can.”

It took Anand Patwardhan 14 years to make the three-and-a-half-hour-long Jai Bhim Comrade (2011), which follows the journey of Dalits who walk the path of the teachings of Ambedkar, but also ascribe to Marxist ideas. The filmmaker has been, for over four decades, documenting India’s descent into Hindu fundamentalism. His films paint a large canvas of society with many protagonists— “the people who populate our world, those suffering as well as perpetrators.” While it is impossible to stay in touch with each person who has stood before his camera, his long view of time is evident in one of the scenes from Jai Bhim Comrade: In Mumbai’s Ramabai Nagar slum, he asks the name of the infant born to an activist; the mother replies, “Samta.” The next abrupt shot shows a little girl aged about 10, within an almost identical setting as the previous scene; Patwardhan’s voice is heard asking her name, and she replies, “Samta.”

Patwardhan takes a few years between his films to travel across India, showing his films to people. Jai Bhim Comrade was screened among Dalit communities across the western Indian state of Maharashtra, where it stoked conversations that would go long into the night. After he made Bombay Hamara Shahar (Bombay: Our City) in 1985, one his friends took the film, along with a 16-mm projector, to Mumbai’s slums. “She kept a diary of all the screenings,” Patwardhan says with a smile.

Many of the contemporary Dalit poets and singers featured in Jai Bhim Comrade were arrested for their supposed links with Maoist ideologues. For five years after the completion of the film, Patwardhan was an active part of the movement to get these young women and men released, which involved going all the way up to India’s Supreme Court. Previously, during the making of Bombay Hamara Shahar, Patwardhan became part of the movement for the rehabilitation of displaced slum-dwellers; it included sitting on a hunger strike with the displaced people. When renowned Hindi film actor Shabana Azmi also joined the hunger strike—after having watched Bombay Hamara Shahar—the government moved swiftly to rehabilitate some of those who had been displaced. “For me it was a natural process [to be part of the movement for rehabilitation]; I did not think about it,” Patwardhan maintains, “Even though the film got a lot of critical acclaim and won a National Award, the demolitions continued.”

Patwardhan is no stranger to the question, “What have you done for the people you have featured in your film?” He considers it a legitimate one, especially when making films about injustices. “One cannot just make a film only to forget the issue after it is over,” he says.

However, the possibility of a relationship of dependence is a real one, even as Monteiro feels that it is impossible to work if the protagonists are patronized to, instead of being viewed as co-collaborators. And such an approach would require stating one’s role clearly, as a filmmaker, and not a social activist. “It is a tricky terrain,” Jayasankar adds, “The only thing I can guarantee is that the film shows the person in a dignified way, but I am not a savior.”

Spun differently, the same question can come from the people in the films themselves: “How will your film change our life?” Patwardhan doesn’t hesitate to state that none of his films will change the situation he is bearing witness to, in any concrete way. “Hopefully, it would plant a seed of doubt, and get people to stop dismissing people’s struggles, and dispel the myth that the poor are stupid. The so-called uneducated are often smarter than the educated. It is never a question of intelligence or education, but a question of opportunity.”

Priyanka Borpujari is an award-winning journalist based in Tokyo. She has previously reported on issues of human rights and justice from across India, El Salvador, Indonesia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Argentina