There’s an age-old question that every filmmaker wrestles with: How to start a film? In the case of Apart, it took until the end of editing to find the beginning.

Apart, by Oscar-nominated Jennifer Redfearn and Tim Metzger, takes an intimate look at three incarcerated women trying to maintain relationships with their children. The film follows them on their journey through an innovative reentry program and after release, as they try to repair the damage from years of separation.

Partners in life and in film, co-producers Redfearn and Metzger talked to over two-dozen women in Cleveland’s minimum-security prison. "All were concerned about finding work and housing," says Redfearn, Apart’s director. "I was particularly struck by the conversations we had about restoring relationships with their children." Both she and Metzger, the film’s cinematographer, were also struck by two statistics: The number of women in US prisons has increased over 800% since the War on Drugs began in the 1980s. And 80% of women entering the system are mothers.

Coming up with an opening sequence "was a tricky thing to get right," Metzger admits. "We’re trying to introduce each of the women. We’re trying to introduce the focus of the film, which is on their relationships with their kids. We’re trying to introduce the setting of the prison and roughly how long they’ve been there. We’re trying to introduce the incredible statistic of how much incarceration has increased. It was important to include mention of the War on Drugs too. So there was a lot to fit in—and lead into the [reentry] program."

The Scene

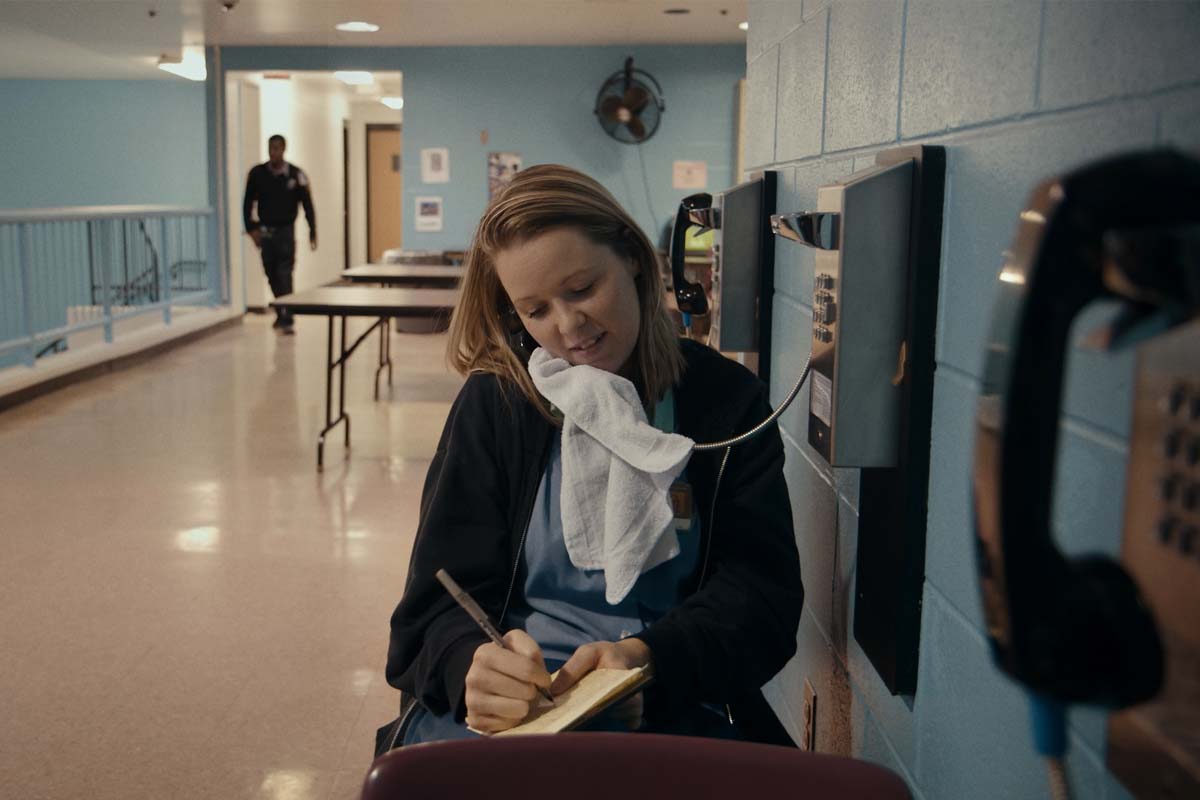

The opening sequence starts with an establishing shot of the prison surrounded by a razor-wire fence. Then it plunges straight into the world of these three women. We find Amanda on the phone, in a dingy hallway, with her tight-lipped eight-year-old son, Tyler. They play a game she invented to get to know him better. She asks, "Which do you prefer: Bunk bed or regular bed?" She listens, then responds that she prefers a regular bed too, after sleeping in a bunk bed for six years. With that, we know how long she’s been locked up.

We first encounter Lydia lined up for breakfast. As unidentifiable globs of food are heaped onto her cafeteria tray, she says in voiceover, "I literally just want to sit with my kids and my husband and watch a movie." Cutaways take us to Toledo, where her family dons winter gloves to go outside and play. Her voiceover continues as she eats: "I’ve been gone too long and lost too many holidays and moments and memories that I’ll never get back." Those moments include this snowy scene of the boys and their dad taking a sled to the park. Lydia’s scene ends with her being counted in yet another line.

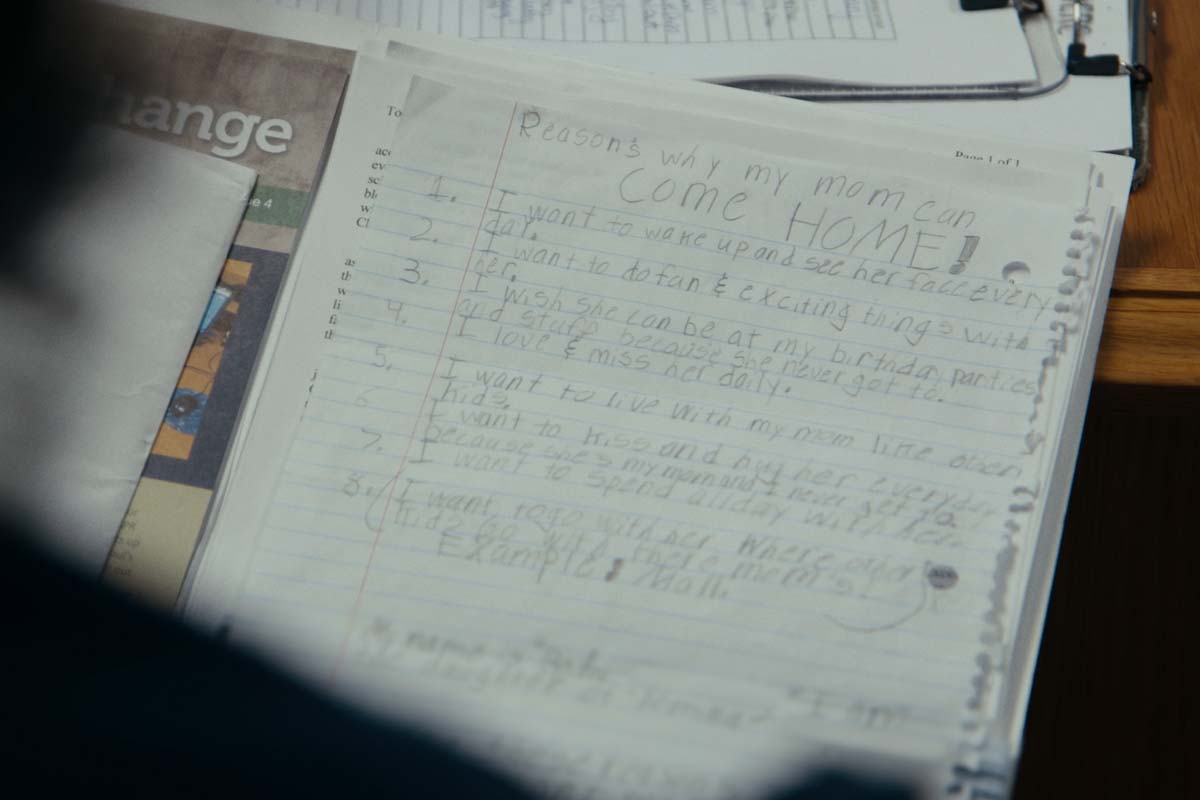

We meet Tomika as she’s reading a letter out loud from her daughter, Bailee. It’s headlined "Reasons why my mom can come home!" The grade-schooler has a numbered list, as we see in a cutaway of her handwriting on notebook paper. Tomika laughs when she reads, "I want to go with her where other kids go with their moms. Example: the mall." She wipes away a tear.

The scene cuts to 10 incarcerated women walking down a corridor towards an exit, followed by text cards with the two statistics. The women are counted, loaded and locked into a van which, we soon learn, is taking them to the reentry program. The two-and-a-half-minute sequence ends with the film’s title.

Scene Breakdown

The original cut of Amanda’s phone call was seven minutes long. Despite being poignant and engaging, they couldn’t find a good place for it in the film. Ultimately they led with this very compressed version.

This is one of the rare occasions in which the camera was on a tripod. "It’s a static scene to begin with: a phone call," Metzger explains. "We wanted to start the film with a solid frame to communicate the static nature of prison." The phone is the primary way Amanda tries to stay connected to Tyler, who lives three hours away and can visit only three or four times a year. "Sadly, that’s a common issue for families with a loved one in prison," Redfearn observes. "This scene speaks to the difficulty of trying to parent from prison and Amanda’s determination to defy the limitations and maintain a bond with her son."

Lydia was the first to be released, so they had limited coverage of her inside the prison. They picked this breakfast scene for its banality. "A typical person starts their day in the kitchen, making themselves some breakfast," Metzger says. "Showing something as banal as breakfast in the prison is a way of getting at how all of the elements of prison life can wear a person down." Redfearn adds, "It’s the steady accumulation of the little things, like not having breakfast with your kids or getting them ready to go out in the snow. This scene allowed us to show the separation and loss felt on both sides. Just like we spent time with the women off-camera, a great deal of time and care went into getting to know their families and making sure they felt comfortable with us and the project. Including this small moment of Derek and the boys in the opening sequence is our way of hinting to the viewer that the families will play a more significant role as the film unfolds."

Regarding Tomika’s scene, the director states, "Connection is one of our most important basic human needs, and as Tomika told us, letters like this from Bailee helped her make it through. Seeing Tomika’s reaction to the letter, we feel not only the sense of humor that both Tomika and Bailee have, but the pain of separation that cuts through it. This moment of Tomika with her prison counselor was initially part of a much larger scene. Still, we felt the reading of Bailee’s letter was a powerful way to introduce Tomika and her relationship with her daughter. Sometimes the simplest moments can be the most profound."

The shot of women heading towards the exit does two things: "It starts the process sequence of getting them out of the prison," Metzger says. "It also shows one woman after another going down this drab hallway. Metaphorically, you start to think about all the women. And that’s where we put the text cards" with the statistics.

As the women file outside, Metzger continues, "It shows them being counted and treated like bodies to load into a van, which is a contrast to how they’re later treated in the reentry program, where they’re called by their first names." The sequence ends inside the van as they drive away from prison. "They’re going somewhere. It’s the movement that gets the film going."

The Gear

The filmmakers wanted a small footprint, especially inside the prison, so most times it was just the two of them, with Metzger on camera and Redfearn on sound. The primary camera was a Canon C300, mounted with Canon EF lenses. The workhorse lens was a 17–55mm (T2.8)— "an overlooked gem," according to the cinematographer. Knowing he’d be in small spaces and would need establishing shots, he wanted a lens at least 18mm on the wide end. And because he wanted the close-ups to be portrait-like and free of distortion, 55mm felt right.

"I love the look and feel of a beautiful prime lens as much as the next DP, but for observational filming I generally prefer zooms, which I treat as variable primes," Metzger explains. The zoom lens was also the cinematographer’s hat-tip to the vérité pioneers he admires, like Frederick Wiseman, the Maysles brothers and Barbara Kopple. "In observational mode, I’m trying to emulate my heroes," he says. "Part of that means using a zoom lens with similar focal lengths to what they had."

Eye height was also important to Metzger: "I want to bring the viewer into the experience of the people I film as much as possible. That always means getting the lens at the same height as people’s eyes." Because he was taller than the three, he couldn’t prop the camera on his shoulder, but needed to hold it chest high. That necessitated a lightweight camera package. In a few low-light situations, he used a gimbal mounted with a Sony a7S II.

"It was very important to us that there would always be a woman on crew," the cinematographer notes. But because they couldn’t find a female sound recordist in Cleveland and couldn’t afford to fly one in for each shoot, "Jennifer learned how to record sound. The women really appreciated seeing her lift that heavy boom pole all day." Her gear was a MixPre-6 field mixer, Sennheiser G3 lavaliers, Sennheiser MKH 416 boom mic, and Sennheiser ME66 shotgun on camera.

The Production

Before seeking permission from the Northeast Reintegration Center prison, the filmmakers sought it from the nonprofit that ran Chopping for Change, the reentry program. In addition to teaching the women employable culinary skills, the program provides counseling and job training, and teaches workplace skills. It was in that safe space where the filmmakers did sit-down interviews with their protagonists (using an EyeDirect and a Sigma 50mm prime). In prison, they were always accompanied by a public-relations official.

Consent was ongoing. "Issues of representation and consent were at the top of our mind throughout this film," Metzger says. "Women in prison are told where to be, what to do. Their lives are controlled in every way." The filmmakers frequently checked if their protagonists wanted to continue with the day’s filming—or with the film at all. "At least in this one aspect of their lives, we wanted to make sure they had full control and autonomy."

In the broader context, Redfearn maintains, "The issues raised in this film are part of a much larger conversation we’re having in the US about inequality, racism, drugs and mass incarceration. We made Apart as one piece of this wider conversation, with a focus on maternal incarceration."

Metzger observes about Apart’s opening sequence, "We wanted to get across that this is a film that’s predominantly observational and at the level of individual women experiencing prison. It’s not about experts. These women are the experts of their own lives."

Apart makes its broadcast debut on PBS’ Independent Lens on February 21 at 10:00 p.m. ET. The film will also be available on PBS.org and the PBS Video app.

Patricia Thomson is a longtime film journalist and a contributing writer for American Cinematographer.