The last few years have been deemed by many as the Golden Age of Documentaries, but for the majority working in the nonfiction landscape, it’s a paycheck-to-paycheck existence that does not include health care, let alone benefits like a 401(k) and paid vacations.

The last few years have been deemed by many as the Golden Age of Documentaries, but for the majority working in the nonfiction landscape, it’s a paycheck-to-paycheck existence that does not include health care, let alone benefits like a 401(k) and paid vacations.

While Hollywood lives and dies by its labor unions, for the nonfiction community, being unionized is a privilege that few can afford. For example, for a doc director to become a Directors Guild of America (DGA) member, they must be hired by a signatory company to direct a project or develop a feature-length project. For that to happen, according to the DGA’s website, “an initiation fee for directors joining on low-budget [under $11 million] documentary feature is $3,500, with 40% payable up-front and the remainder paid out over a year. The regular [non-low-budget] initiation fee is $13,416. If you join as a low-budget director, you simply pay the additional $9,916 when you do a ‘regular’ project.” In other words, a doc director needs to find a production company that is willing to pay not only their salary, but also those signatory “regular project” costs to become a DGA member, which comes with a health-care plan.

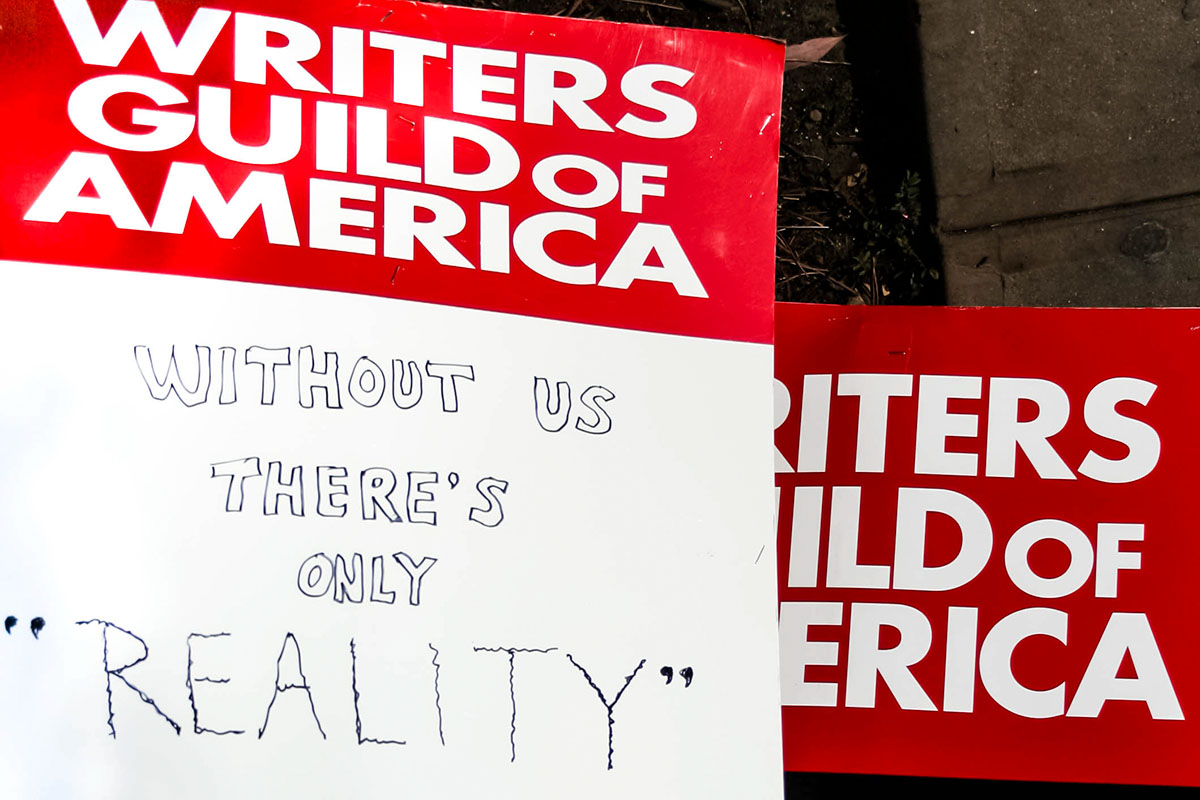

Unions like the DGA, the Writers Guild of America (WGA), and the Motion Picture Editors Guild (IATSE Local 700) ensure secure safe working conditions, fair pay, holidays and health care for the majority of scripted directors, producers, writers and editors, which in turn allows them to create content for a multi-billion-dollar industry and build sustainable careers.

But unlike scripted film and television, there is no one-size-fits-all contract for documentary work. There is no Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP)—a trade association responsible for negotiating virtually all industry-wide guild and union contracts, including those with the DGA, the WGA and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA).

So the majority of documentary directors, editors, writers and producers work as independent contractors. But working with no financial security or health benefits has become an issue with the advent of streaming and the influx of funding that’s come with it. Documentary features and series today have become as ubiquitous, and as prestigious, as premium scripted fare. The category is a cornerstone of the business model for outlets like Netflix, Hulu, HBO Max, Amazon, and Apple TV Plus and Disney Plus.

"It's hard to ignore the fact that what you made is making other people a lot of money."

- Claire Gordon, showrunner and executive producer of the Netflix docuseries Explained

“As someone who produces nonfiction content, you can see your shows doing as well as a lot of these scripted shows on the streamers,” says Claire Gordon, showrunner and executive producer of the Netflix docuseries Explained. “You see in these top 10 lists that a nonfiction series or doc is side by side with these big budget scripted projects.”

What the nonfiction community is asking for isn’t so different from what WGA members were asking for in 2017. At that time movie studios represented by AMPTP reported $51 billion in operating profits—nearly double their profits in 2007. According to Variety, that led to WGA members threatening to strike because, by the guild’s math, 66% of that $51 billion, or about $33.7 billion, was directly derived from scripted film and TV production that all started with the labor of WGA members. But many writers, in particular those earning "middle-class" wages, saw their compensation go down. So, the WGA sought to raise the studios' writing wages. Eventually the AMPTP and the WGA reached an agreement on a new contract that improved pay for writers, which averted a strike.

“It's hard to ignore the fact that what you made is making other people a lot of money,” says Gordon. “Especially since you know that in a couple months when you're feeling pretty burnt out at the end of a project, you’re going to have to live off savings until you can find your next gig.”

In 2020 the NonFiction “Union”—a creative coalition for reality and documentary professionals—reported that over 80 percent of professionals working in nonfiction and documentary television did not have health insurance and worked significant amounts of unpaid overtime. The goal of the Los Angeles-based coalition was to “foster a movement toward all nonfiction workers being incorporated into existing unions.”

Since 2012, WGA, East (WGAE) has been trying to do just that for documentary writer-producers. The guild has been working to organize the nonfiction sector in New York City by negotiating union contracts with documentary production houses to ensure better wages, hours and health benefits. (The Producers Guild of America (PGA) is not a union and does not do collective bargaining.)

"We’ve heard from talking to people in the documentary community that when they are working on their [project], they can work seven days a week for multiple weeks straight."

- WGA East Executive Director Lowell Peterson.

In the last decade, the WGAE has unionized nonfiction production companies including Lion TV, Sharp Entertainment, Vox Entertainment, Vice, NBC News Service and Thirteen Productions. Last year the guild began negotiating a contract with Alex Gibney’s Jigsaw Productions to unionize freelance employees in associate producer, co-producer, field producer, segment producer and post producer positions.

“We’ve heard from talking to people in the documentary community that when they are working on their [project], they can work seven days a week for multiple weeks straight,” says WGAE Executive Director Lowell Peterson. “They don't get anything extra for that. So they just burn out at the end, and that gets old after a while.”

Peterson acknowledges that each union contract is specific to each production house, but he says that there are a “a few priorities in the 2019 Vox contract” that he hopes to negotiate with fellow New York documentary production houses. Those priorities include the following: (1) Minimum Pay Rates: “All of our contracts guarantee minimum wages, but allow for individual negotiations above the minimums”; (2) Work Week: “If a weekly employee who is not covered by overtime provisions works a sixth or seventh day, they will be paid for that day at ⅕ their weekly salary rate [showrunners exempt]”; (3) Rest Period: “Eight hours during a regular work day and six hours during travel. If the company violates the rest period, a $35/hour penalty for hourly employee and $100 flat for weekly employees will apply”; (4) Holidays: “Ten company-designated holidays; five days off after five months”; (5) Health Benefits: “Starting on the first day of employment, Vox pays $23 per day to the Flex Plan. The employee could either use that money for a healthcare plan, or use the money for health-related expenses. The Flex Plan is a portable health insurance plan that will eventually allow producers to move from company to company without changing plans.”

Gordon produces Explained out of Vox Entertainment. In 2019 she became a WGAE union member after Vox Media’s 350-member unit began bargaining their first contract in April 2018. “It was pretty easy and pretty fast for Vox to recognize the union,” says Gordon. “I think that was partly because Vox is a company that has a lot of strong, progressive values.”

In October, Alex Gibney released a statement about Jigsaw’s negotiations with the WGAE: “We at Jigsaw Productions are delighted to work with the WGAE and the freelance employees to try to come up with a contract that can become a model for the nonfiction industry to follow.”

“At some point the industry needs to be rational enough to know that if you want professional content, you have to pay professionals to do it.”

- WGA East Executive Director Lowell Peterson.

One reason nonfiction production houses have not yet started union negotiations with the WGAE is, arguably, because of money. Unlike scripted content, documentaries are not a multi-billion dollar industry. In addition, one-off docs and docuseries have been made by prominent production houses without the extra union costs for decades. The question becomes, Why rock the boat and ask for more money from networks and streamers who are already giving nonfiction production houses more money than ever before to make content?

“We try to talk to the companies that are writing the checks and say, ‘Do the right thing,’” says Peterson. “Because at some point the industry needs to be rational enough to know that if you want professional content, you have to pay professionals to do it. They are not going to just do it out of the goodness of their hearts. They are going to do it if there's a case made to them that says, Look, you need to do this in order to get the good content because the union is organizing these [production] houses.”

While Peterson admits that there is an attempt to work from the top down, he says that the WGAE is primarily working from the “ground up.” Meaning, they speak to individual writer-producers and build a campaign in a particular production company to bring about multi-employer negotiations, proper pay, health-care benefits and, in the best-case scenario, a contract that includes residuals.

Peterson says that the WGAE will work on unionizing nonfiction production houses for “as long as it takes” and he is not opposed to pressuring conglomerates like Netflix, Discovery and Amazon to pay up.

“It's not a lot more money they would have to pay compared with the economics of this business,” says Peterson. “They can afford to pay for it. So [on our part] it is partly moral persuasion, political persuasion and embarrassment—like, Shame on you for not paying people enough to be able to sustain a career.”

Addie Morfoot has been covering the entertainment industry for the last 18 years. Her work has appeared in Variety, The New York Times Magazine, Crain's New York Business, The Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, Documentary and Adweek.