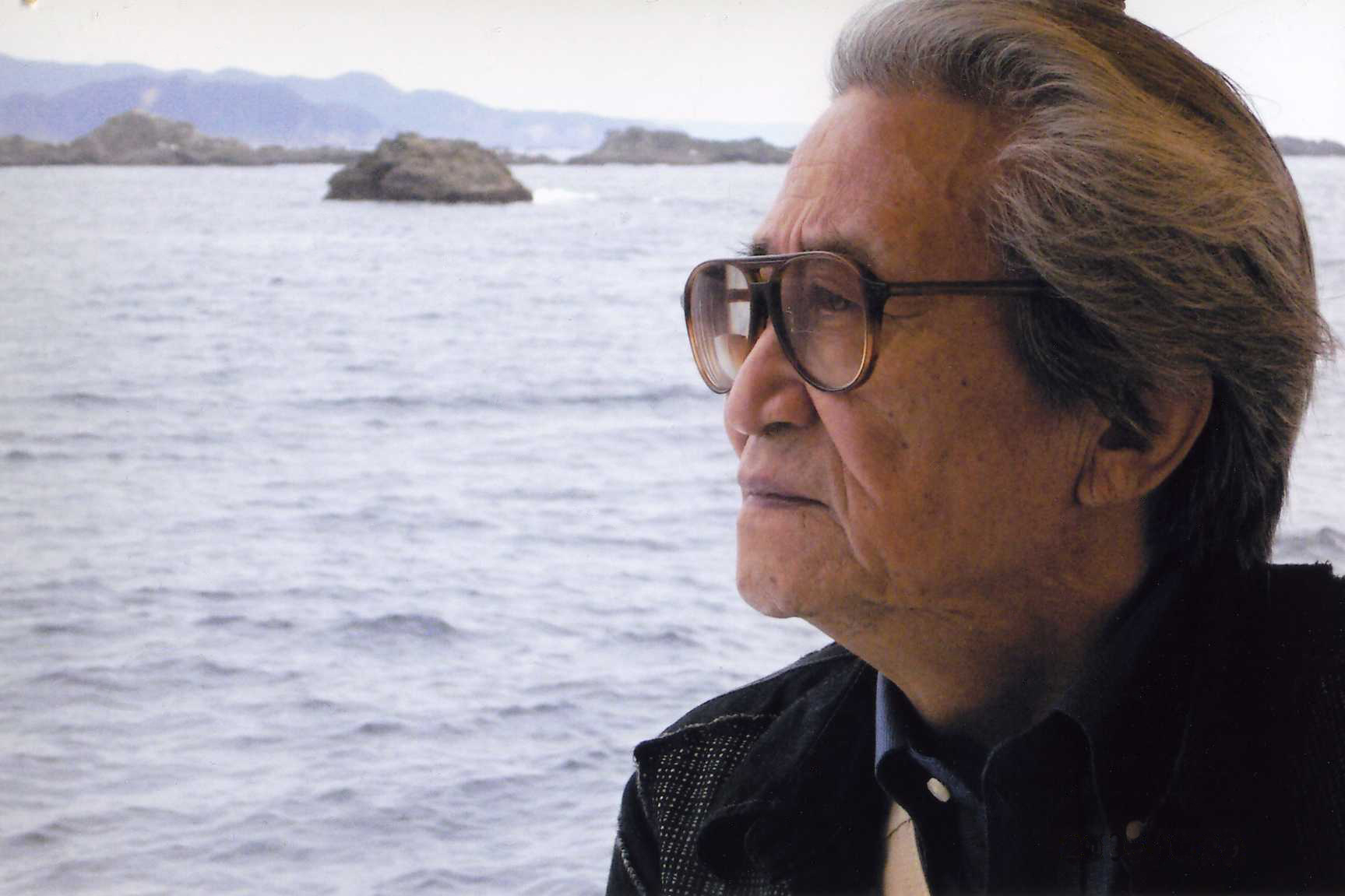

Noriaki Tsuchimoto is a towering figure in Japanese documentary cinema, but only known by name and reputation in the West. Beyond festival screenings, his films rarely show here. That is about to change, however. Following a program held at the Open City Documentary Festival in London, the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, New York will host a retrospective dedicated to Tsuchimoto’s work; the series runs from November 12-27. Before this rare opportunity occurs, it’s time to take a hard look at just what makes his documentaries special.

Noriaki Tsuchimoto is a towering figure in Japanese documentary cinema, but only known by name and reputation in the West. Beyond festival screenings, his films rarely show here. That is about to change, however. Following a program held at the Open City Documentary Festival in London, the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, New York will host a retrospective dedicated to Tsuchimoto’s work; the series runs from November 12-27. Before this rare opportunity occurs, it’s time to take a hard look at just what makes his documentaries special.

With a body of work spanning six decades and over 100 movies, Tsuchimoto’s career can be roughly divided into three parts: the early shorts directed for Iwanami Productions; the series of films dedicated to Minamata disease; and the later documentaries on Afghanistan. Each phase of his career has movies worth watching. And as with any artist, his focus and aesthetic changed over time.

Tsuchimoto’s entry into the world of cinema was a matter of happenstance and being in the right place at the right time. Though born in Gifu Prefecture, he grew up relatively poor in Tokyo. At the end of World War II, he lived with relatives in Setagaya Ward, next to Toho studios. During these final days, citizens would stand guard for potential nocturnal air raids. It was at this time Tsuchimoto would keep watch with film crew, including cameraman Keiji Yoshino. Tsuchimoto would strike up conversations with Yoshino pertaining to craft. Years later, the cameraman would recommend Tsuchimoto to Iwanami Productions, a company that specialized in making promotional and educational films for companies. Starting in 1956, Tsuchimoto worked as a location manager before getting a crack at directing as a freelancer.

Tsuchimoto’s entry into the world of cinema was a matter of happenstance and being in the right place at the right time. Though born in Gifu Prefecture, he grew up relatively poor in Tokyo. At the end of World War II, he lived with relatives in Setagaya Ward, next to Toho studios. During these final days, citizens would stand guard for potential nocturnal air raids. It was at this time Tsuchimoto would keep watch with film crew, including cameraman Keiji Yoshino. Tsuchimoto would strike up conversations with Yoshino pertaining to craft. Years later, the cameraman would recommend Tsuchimoto to Iwanami Productions, a company that specialized in making promotional and educational films for companies. Starting in 1956, Tsuchimoto worked as a location manager before getting a crack at directing as a freelancer.

For such an industrial outfit, Iwanami allowed for formal experimentation from its filmmakers, many of whom were, ironically, leftists subverting the content and messages they were given by the company. In this way, Iwanami’s creative permissiveness can be likened to the Centre Office of Information in Britain, another pragmatic entity where daring creation flourished. Such radical technique Tsuchimoto expressed in one of his efforts for the company: An Engineer’s Assistant (1963). Although made for Japanese National Railways (JNR) to promote train safety after a wreck killed 160 people, the color short ultimately follows a fireman on a steam train. Reminiscent of Artavazd Peleshian’s train movie End (1992), Engineer’s Assistant is a montage-based actioner comprised of accumulated details: the loaded hand signals of a train conductor; a graphic transition from an emergency flare to a rising sun; the heavy breathing on post-sync sound as an engineer’s assistant runs through a simulated accident. What Tsuchimoto conveys is the precision of movements performed so routinely that they become ritualized, exuding a mechanized professionalism straining against a tight schedule. The engineer and the assistant are one with the train.

At this time, filmmakers working for Iwanami would often meet up, forming what has been called the “Blue Group,” to discuss and analyze projects that they were working on. It was a casual setting for the crew to hang out, commiserate and workshop. Yoichi Higashi and Shinsuke Ogawa—the other major figure in post-war Japanese documentary cinema—were also part of this group.

The following year, Tsuchimoto made On the Road: A Document. Far more subversive than Engineer’s Assistant, the movie ended his relationship with Iwanami. Commissioned by the Metropolitan Police, the movie was supposed to demonstrate proper traffic safety. The finished product was far from the mark and ultimately shelved for four decades. One can see why: In direct opposition to the backers, Tsuchimoto worked with a drivers’ union to record the plight of cabbies. Pushing montage further than Engineer’s Assistant, Tsuchimoto’s objective is not to explain but to evoke, that of a mood and atmosphere pervading post-war Tokyo: a chaotic hodgepodge of half-built buildings, incessant construction, and haphazard traffic in lane-less thoroughfares. What Tsuchimoto ultimately conveys is a sense of isolation and alienation at the heart of living in the city at the time. At one point he fixes his camera on a Cryon plastered on the façade of a building. The scrolling text announces the death of a four-year-old girl and the critical condition of her mother, and then nonchalantly moves on to the weather—the tragic news is just a part of everyday life in Tokyo.

The next year, 1965, Tsuchimoto made for TV The Children of Minamata Are Living, the first in a decade-spanning series on the city and the disease. What he found while filming in Kumamoto Prefecture were families resistant to media coverage and suffering since 1956, when the first cases of mercury poisoning were publicly recorded. Chisso Corporation, a powerhouse chemical company, had been dumping an organic compound of the element directly into the sea, tainting fish (the area’s main industry) in the process, which fishermen would catch and innocent people would eat. Tsuchimoto was so shaken up by the experience that he questioned whether his movie would further add to the people of Minamata’s misery. Producer Ryutaro Takagi convinced Tsuchimoto to reconsider, leading him to make Minamata: The Victims and Their World (1970), a high achievement in his career. The movie documents the many people affected by Chisso’s actions, such as a boy afflicted with ataxia (lack of muscle control) asking the filmmakers about the waters in Tokyo. In fact, Tsuchimoto is more of a presence here than in his prior works, appearing on camera and asking questions in voiceover. It’s part and parcel with confidence in his filmmaking, a sense of pacing and rhythm that perhaps wasn’t as mature in the PR films. As with Engineer’s Assistant and On the Road, sound and image aren’t in sync, which Tsuchimoto puts to creative use. Consciously selecting the appropriate combination of audio and visual, he creates a quietly dislocating, disorienting effect that makes one more aware of what is being seen and heard. Never once does Minamata feel sentimental. Rather, Tsuchimoto offers it as a sobering document made of a patchwork of imagery, sprinkled with title cards that stitch the shots together, providing context for the events depicted onscreen. The movie climaxes with outrage as victims, who have purchased stock in Chisso, attend a meeting to confront board members with the admission of their responsibility. Here, in contrast to the rest of the footage, the camera is battered around as it gets swept up with the angry mob rushing the stage to corner the corporate suits.

None of the volcanic ire in Minamata’s finale seeps into The Shiranui Sea (1975), for this installment in the series—one of the longest at two-and-a-half hours—is more reflective and episodic, with fade-to-black scene transitions. In a way, it’s an extension and refinement of the earlier documentary. Tsuchimoto returns to a few of the victims first seen in Minamata. Onscreen, he asks how his film crew should film them, allowing for empathy and communal, participant filmmaking. Sometimes the director’s response stands for the viewer’s own, such as questioning a public medical doctor’s lack of first-hand encounters with full-blown Minamata disease victims as unconscionable. And other times, he has the artistic instincts to remove himself from the scene, such as a moment between a teenage victim and a doctor at the site where the disease was first discovered. The girl starts to cry at one point, not knowing what she can do with herself. The doctor speaks to her directly and honestly, while still retaining an air of comfort. This is a crucial moment in the film that gets to the heart of why Tsuchimoto’s cinema is worthy: It documents a heartrending conversation at a respectful distance, allowing the moment to happen and emotion to filter into the scene.

None of the volcanic ire in Minamata’s finale seeps into The Shiranui Sea (1975), for this installment in the series—one of the longest at two-and-a-half hours—is more reflective and episodic, with fade-to-black scene transitions. In a way, it’s an extension and refinement of the earlier documentary. Tsuchimoto returns to a few of the victims first seen in Minamata. Onscreen, he asks how his film crew should film them, allowing for empathy and communal, participant filmmaking. Sometimes the director’s response stands for the viewer’s own, such as questioning a public medical doctor’s lack of first-hand encounters with full-blown Minamata disease victims as unconscionable. And other times, he has the artistic instincts to remove himself from the scene, such as a moment between a teenage victim and a doctor at the site where the disease was first discovered. The girl starts to cry at one point, not knowing what she can do with herself. The doctor speaks to her directly and honestly, while still retaining an air of comfort. This is a crucial moment in the film that gets to the heart of why Tsuchimoto’s cinema is worthy: It documents a heartrending conversation at a respectful distance, allowing the moment to happen and emotion to filter into the scene.

In the following decade, Tsuchimoto would branch out by visiting and shooting footage in Afghanistan. Co-directed by Hiroko Kumagai and Abdul Latif, Afghan Spring (1989) documents a transitional period in the country’s history. As Soviet forces leave, the movie depicts a moment of respite for Afghanistan before the Taliban would take power and wreck the country anew. Afghan Spring offers a cross-section of people and places, hopscotching from Kabul and Herat to Hadda and Jalalabad; the crew visits the home of a rebel leader looking after a village, farmers tilling arid fields, and a museum curator safeguarding precious artifacts. The movie is a snapshot of the Afghan people and their mindset, as they offer the film crew their thoughts on war, marriage, and refugees returning from Iran after many years.

After NATO and the US invaded the country in 2001, Tsuchimoto returned to his footage shot in Afghanistan, re-editing it into two short works, some of his last: Another Afghanistan: Kabul Diary 1985 and Traces: The Kabul Museum 1988 (both 2003). The former both provide context on the history of Afghanistan from an outsider’s perspective and depicts developments happening at the time: a successful campaign for education and literacy; and the issuance of deeds—the first in the country—after the new government’s land reformation policy. The latter is important for preserving to film art and artifacts once housed in the museum but destroyed when looted in the ‘90s.

Amid his long, variegated career, Noriaki Tsuchimoto’s approach remained elastic, bending to the contours of the subject matter at hand. Along with Shinsuke Ogawa, he would continue to pursue matters of interest with an abiding determination. Publishing Of Sea and Soil, an essential dossier devoted to the filmmakers, Stoffel Debuysere and Elias Grootaers wrote,“They made films that convey a material understanding of the world they document, films not on a subject but with a subject.” It’s this horizontal relationship that makes these directors endure. Subsequent filmmakers have taken it as a model on which to base their approach. Kazuo Hara, arguably Japan’s most important living documentarian, continues to make movies about and with people on the margins of society, including Minamata Mandala (2020), a six-hour feature on the very disease that was Tsuchimoto’s life’s work. John Gianvito has publicly acknowledged Tsuchimoto’s influence, especially when it comes to the ethics of representation. “Perhaps this sounds a commonplace, an obvious and simple requisite for the documentary filmmaker,” Gianvito wrote, “but it is only deceptively so or we would encounter it more frequently.” Tsuchimoto paid attention, and the quality of his attention was rich. In the end, he shared wealth.

Tanner Tafelski is a freelance film critic based in New York City and the editorial director for Kinoscope, a streaming platform for arthouse cinema. If he isn't watching a movie, he's reading crime fiction.