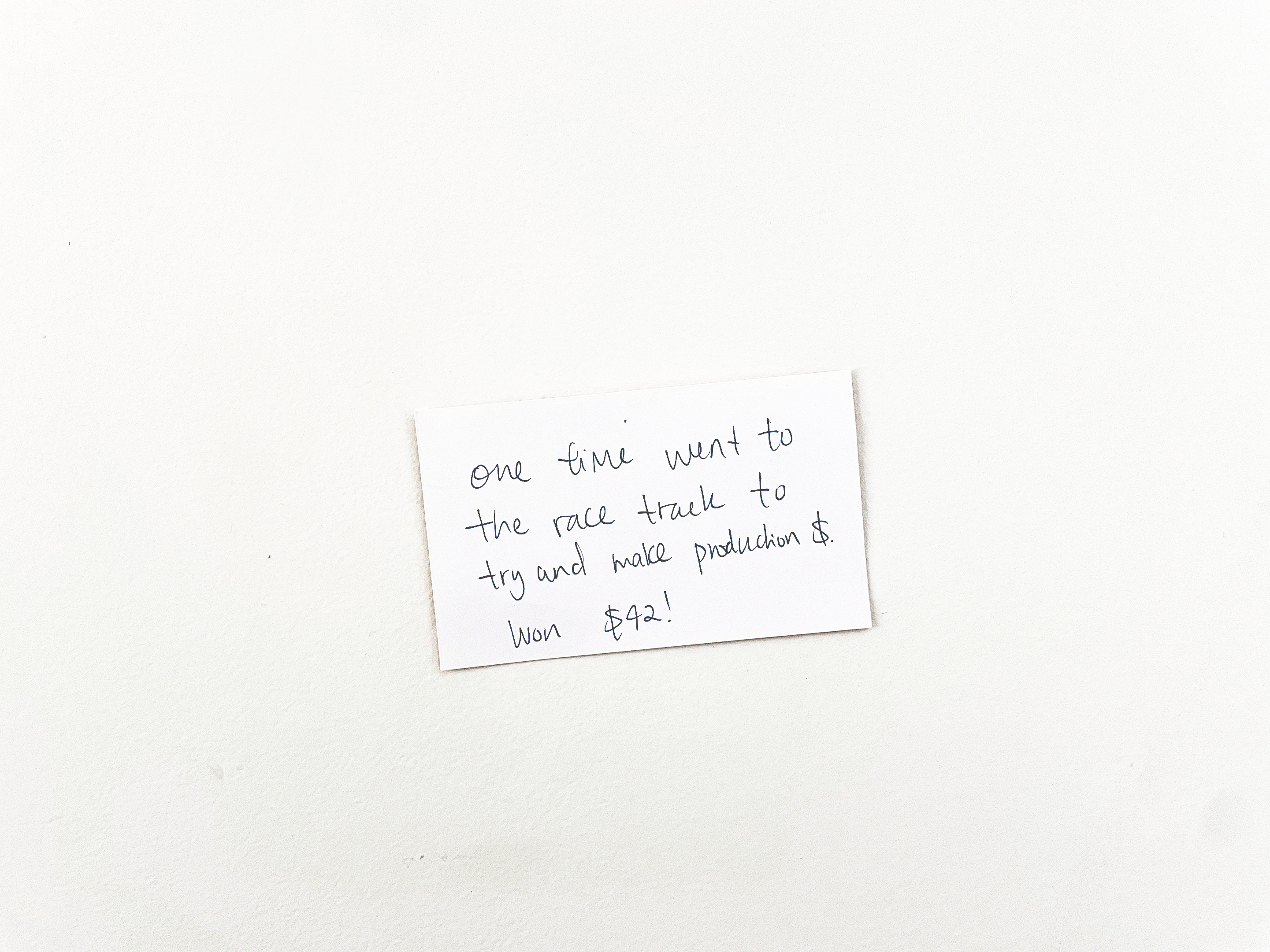

Index cards submitted to the Sources of Income Confessional Board. Courtesy of Sue Ding

Whether we are unemployed creatives, overwhelmed freelancers, or underpaid employees, it can often seem like everyone else has figured it out. Social media is a constant stream of people announcing new jobs, festival screenings, and prestigious grants and awards. Yet more often than not, the filmmaker who had the big premiere, received all the accolades, and even successfully sold their film is still struggling to get by, just like the rest of us. So how are filmmakers actually making a living?

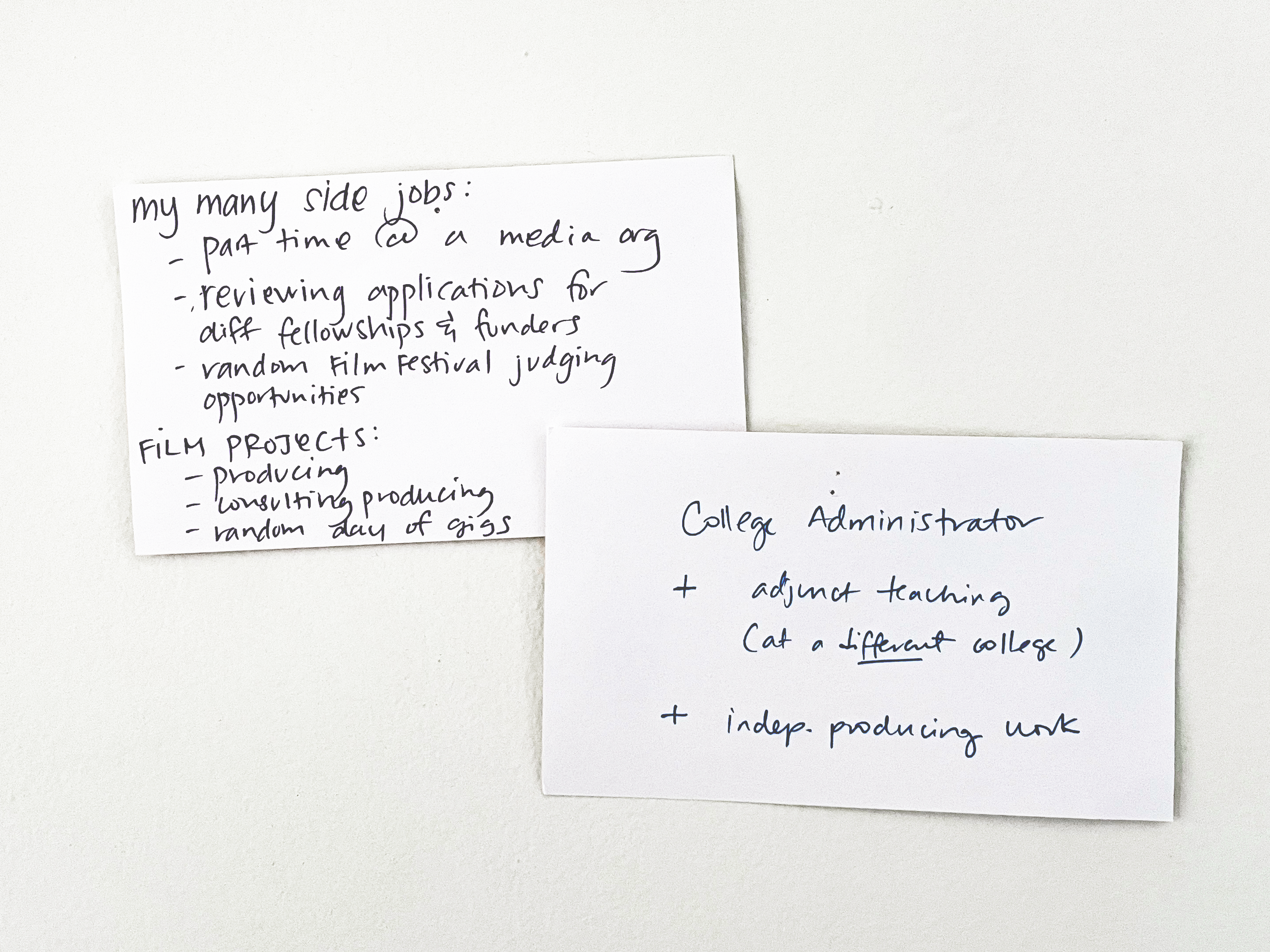

At last month’s Getting Real conference, IDA invited attendees to a “Sources of Income Confessional Board,” hoping to generate an honest, unfiltered portrait of our industry. Conference attendees could anonymously share how they make ends meet, filling out index cards that were posted by staff onto a trifold for passersby to read.

An anecdotal and unscientific overview of the results reveals the following key categories among respondents:

1. Multiple Jobs

“My many side jobs: part time @ a media org, reviewing applications for diff fellowships & funders, random film festival judging opportunities. Film projects: producing, consulting producing, random day of gigs”

“College Administrator + adjunct teaching (at a different college) + indep. producing work”

Having a single source of income was rare among attendees of Getting Real. From more than 80 submissions, only three people were able to sustain themselves solely on income from their own films (whether from grant money or film sales). Only four people relied exclusively on teaching income, and only two people were able to get by exclusively on a non-profit salary.

About half the respondents listed two or more jobs, with many listing four or more. Participants juggled jobs from across the film industry: cinematography, grant writing, post-production, acting, journalism, editing, photography, festival programming, impact strategy, archiving, and A/V support. Teaching, consulting, branded content, and nonprofit work were the most commonly mentioned jobs.

2. Family Support

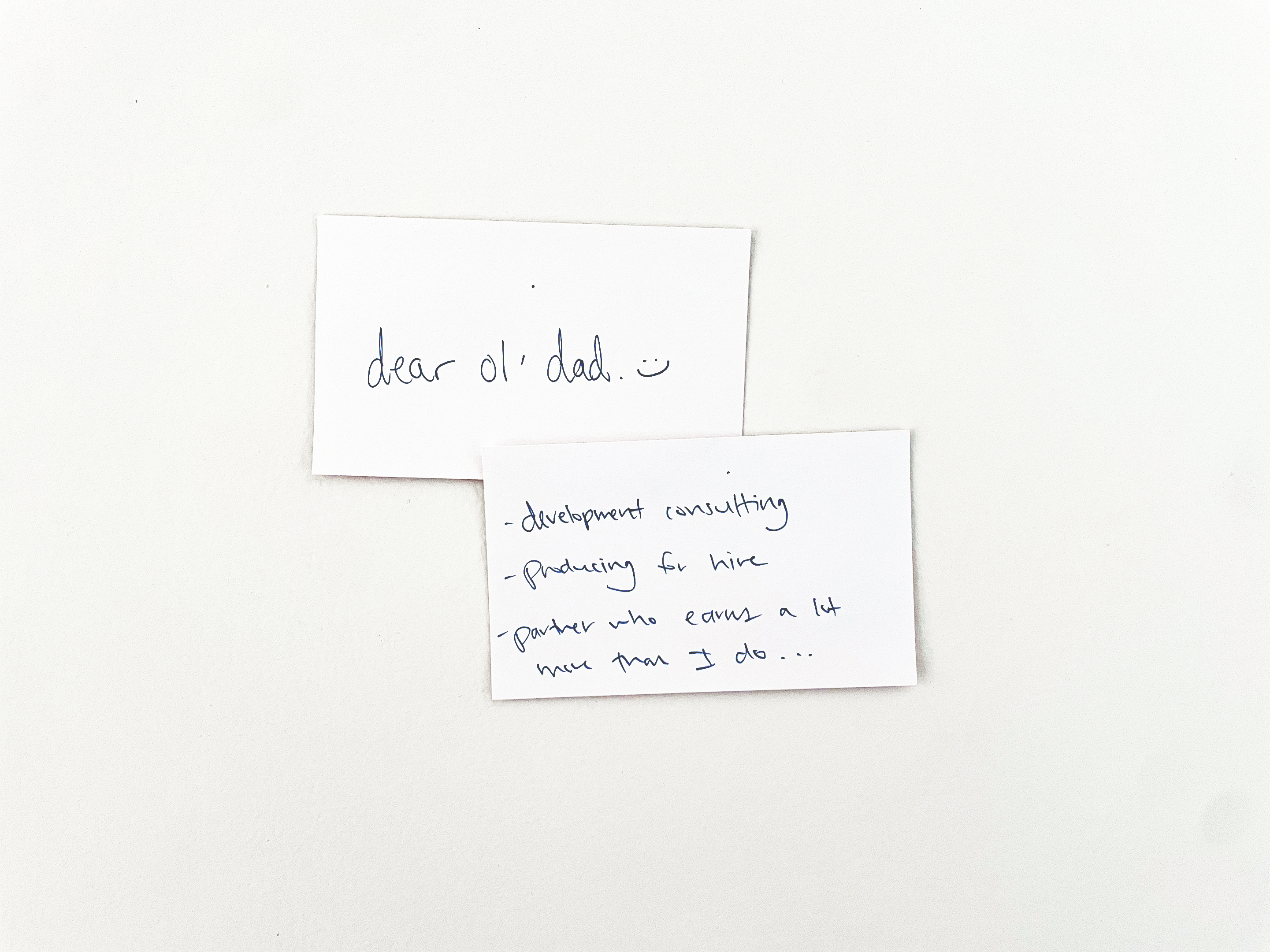

“dear ol’ dad”

“partner who earns a lot more than I do…”

Several respondents listed their spouses as their sole sources of income, with many more mentioning generous or higher-earning spouses among multiple sources of income. Other respondents either lived with their parents or received financial support from them.

No one came right out and said “my family is rich”—although some came close. But as we all know or suspect, many (most?) film careers are built on some degree of generational wealth. Some people might have been too embarrassed to own up to their privilege, even anonymously. But the confessional booth’s audience was also likely self-selecting, with those experiencing financial hardship being the most interested in venting, and the most curious about how others are making ends meet.

3. Commercial/Corporate/Branded Work

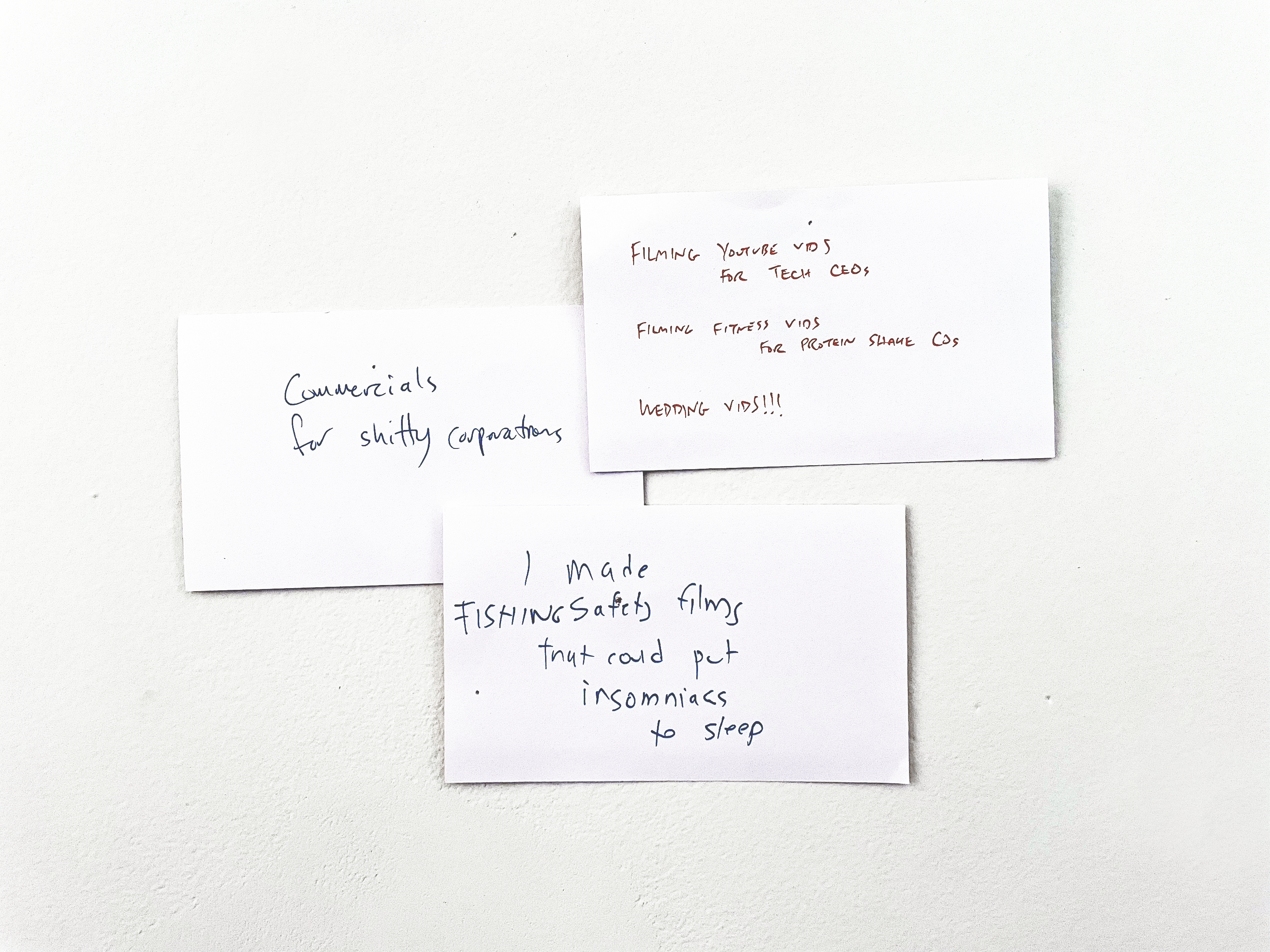

“commercials for shitty corporations”

“fitness vids for protein shake CEOs”

“fishing safety films that could put insomniacs to sleep”

Many submissions included some form of commercial, corporate, and/or branded work—sometimes as a sole source of income, sometimes as one of many side gigs. In addition to churning out social media and “user-generated” content, respondents also mentioned working for tech companies, big pharma, and entertainment press. One respondent wrote that they edit “‘corporate’ documentary (i.e. Netflix + other streamers),” demonstrating the malleability of this category and how we define it.

Some people were clearly unenthusiastic about their commercial work, but in other cases, there was no clear positive or negative connotation. It should be noted that for many people, working on this type of (generally) more highly paid work is the goal.

4. Gig/Part-Time Work

“customer service minimum wage roles”

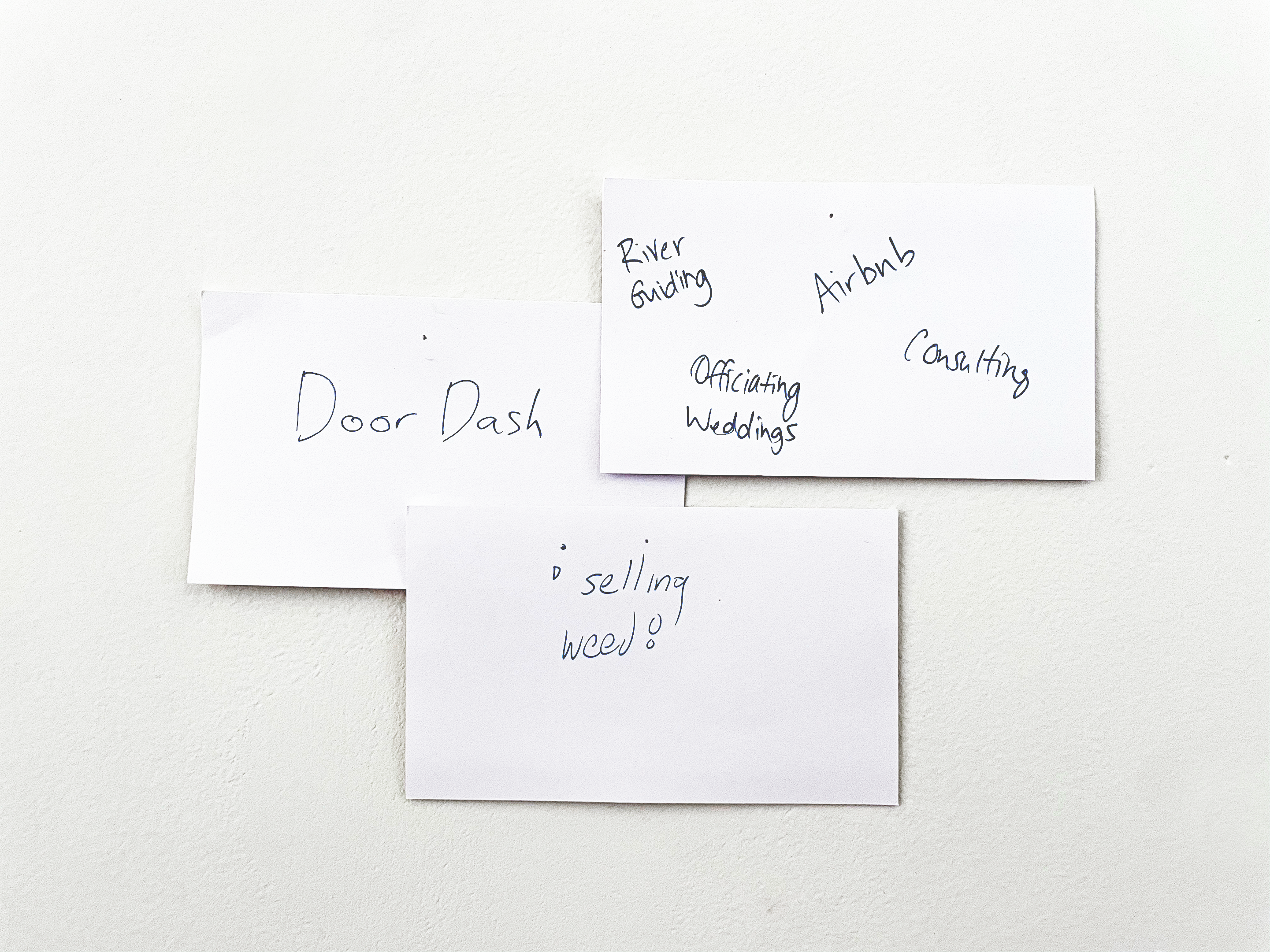

“Doordash”

“officiating weddings”

“¡selling weed!”

In addition to film jobs, many respondents reported engaging in gig or part-time work outside the industry, including bartending, care work, tourism jobs, and catering. This kind of work makes sense for filmmakers in that you can often make your own hours, but it also replicates many of the same freelancing precarities—low pay, lack of health insurance and unemployment benefits, and no guarantee of work.

5. …And The Rest

“One time went to the race track to try and make production $. Won $42!”

Day Jobs: Several respondents had full-time jobs outside the film industry, from government work to hospitality. One respondent was an ER nurse—how?!

Real Estate: A few participants listed Airbnb income, and one person flipped houses. Needless to say, any real estate income involves having money to invest, pointing to some degree of pre-existing wealth.

Grants: Grants only made a few appearances, a dispiriting reminder that grant funding may enable people to make their films, but is rarely enough to live off of.

It was somewhat surprising not to see unemployment benefits listed anywhere, as many in the industry remain unemployed after the turmoil of the last year and a half—but the dry period has lasted long enough at this point that some peoples’ benefits may have run out. And of course, many freelancers may not have been eligible in the first place.

So what can we take away from all this? This industry has always been tough, and times are tougher than usual. Many people are struggling. Many jobs—even and perhaps especially the prestigious ones—don’t pay enough. One respondent noted “earning less than […] $2000 a year for high profile, high visibility positions” in gatekeeping roles.

These “confessions” are a helpful reminder that despite appearances to the contrary, many filmmakers don’t make all—or any—of their income from filmmaking.

There is a lot of shame associated with not being able to support yourself solely from your creative endeavors. Sometimes it can feel like you’re the only one juggling a bunch of random and unglamorous gigs, while still struggling to make ends meet.

Money shame and imposter syndrome are usually things we wrestle with privately, but maybe we can take the Confessional Board responses as a collective cue to let go of these fears and embrace more transparent discussions around income. The need for equitable and sustainable modes of filmmaking affects all of us, after all, and is a question that we can more effectively tackle in solidarity and community with each other.

Sue Ding is a filmmaker and visual artist based in Los Angeles. Her work can be found on platforms including PBS, Netflix, and the New York Times. She also writes and lectures widely on nonfiction filmmaking.