In 2015, the Sundance Institute launched a new initiative to support “inventive artistic practice” in documentary called Art of Nonfiction. After fostering such groundbreaking filmmakers over the years as Khalik Allah, Garrett Bradley, Robert Greene, Sky Hopinka and Kirsten Johnson, among others, the program wound down last year after COVID-19 struck and the program’s founder, Tabitha Jackson, was tapped to run the Sundance Film Festival.

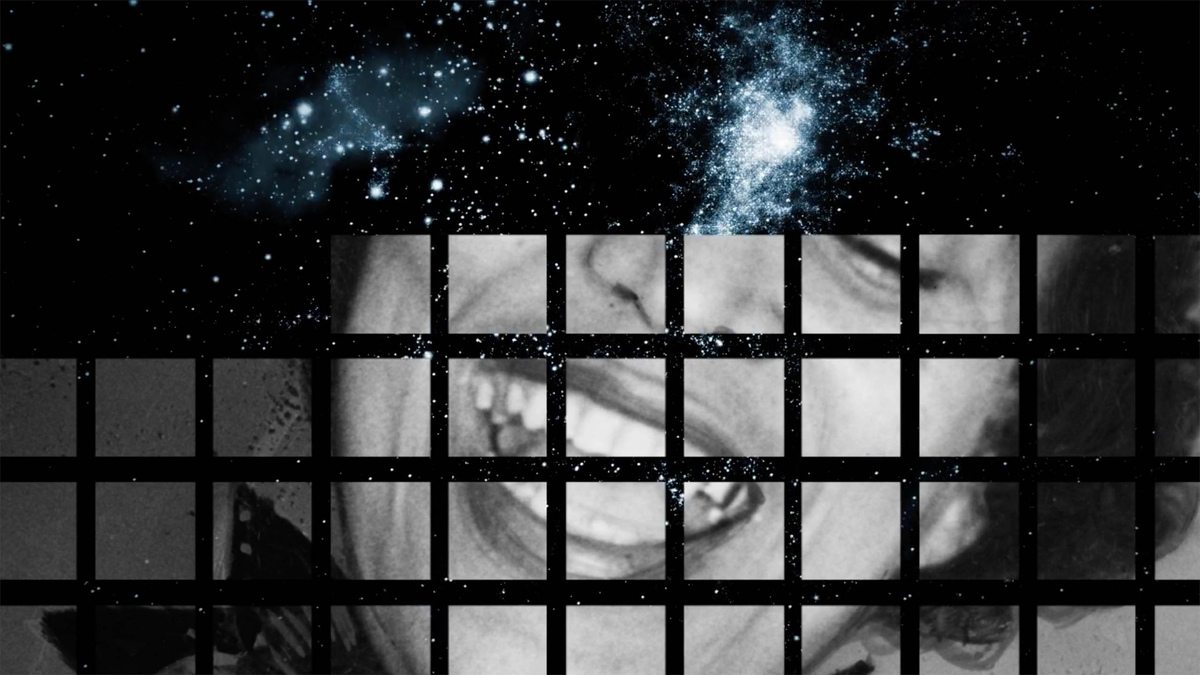

As an indication of the program’s success, this year’s Sundance Film Festival showcased five ambitious and formally exciting new works from Art of Nonfiction alumni: Sam Green’s 7 Sounds, Natalia Almada’s Users, Theo Anthony’s All Light, Everywhere, Sierra Pettengill’s short The Rifleman, and the interactive WebXR experience, Traveling the Interstitium with Octavia Butler, on which Yance Ford was a key collaborator. But with forward-thinking nonfiction cinema still facing unique and especially high hurdles in both funding and distribution, was it too soon for Art of Nonfiction to expire?

“From a funding perspective, it is just as difficult now as it was then to get boundary-pushing work made and seen,” admits Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program Deputy Director Kristin Feeley. “If anything, the landscape is even more precarious; funders and exhibitors more risk-averse.”

Still, the program isn’t coming back, according to Feeley, who maintains that it remains “part of the DNA” of the Institute’s Documentary Program “and will continue in that spirit.” Indeed, Sundance’s Documentary Film Program continues to be “committed to supporting visionary and groundbreaking filmmakers in all its work,” as current DFP Director Carrie Lozano says, with wide support for a range of doc-makers, including such innovative projects as Jessica Beshir’s lyrical Faya Dayi (which also screened at this year’s Sundance Film Festival).

But participants of Art of Nonfiction point to a higher purpose of the program: It didn’t just provide funding, or a safe space for its Fellows to freely cultivate their artistic practice without pressure; more importantly, through Sundance’s muscle and mainstream credentials, it legitimized such work as valid and worthwhile in the marketplace at large. “In a world where everything is about ‘What is the product?’ and ‘Who is your audience?’,” says Anthony, “I had never come across anything like it before.” Adds Ford, “Art of Nonfiction was a place where I didn’t have to talk about my work as non-traditional; it was just the work.” And as Almada maintains, “One of the huge values of something like Art of Nonfiction was to say there’s other ways of thinking about documentary films than about social issues with measurable outcomes. The Art of Nonfiction came to challenge that.”

Despite the Sundance program’s bona fides, however, funding still remains especially difficult for such projects. Grants, for example, while often the lifeblood for documentary filmmakers, are difficult to get for projects that don’t check off easy-to-fill boxes or tackle hot-button topics. As Pettengill notes, “Grant applications require a level of certainty that some creative documentaries don’t have. You’re often trying to fit what the grant wants and guessing what a documentary will be.”

Riel Roch Decter, who produced Anthony’s Rat Film and All Light, Everywhere, says it’s been “tremendously difficult to find funders who want to support these kinds of films consistently over the long term.” While citing such outfits as Field of Vision and Cinereach as crucial backers, he adds, “We have had to rely on a great deal of intrepid one-off private funders and artist grants to help us bit by bit.”

Oscar-nominated director Sam Green (for 2003’s The Weather Underground) says there are not sustainable funding options nowadays for the kinds of experimental live nonfiction event films he’s making, such as the Kronos Quartet portrait A Thousand Thoughts (2018) and his new audio-based 7 Sounds project. “I’m scratching my head,” he admits. “There’s crowdfunding, which isn’t great, and wealthy people—and that’s not a solution for the field.” Certainly, Art of Nonfiction’s $25,000 grants weren’t going to solve all their funding problems, but it provided a necessary piece and a springboard for further funding.

“It totally elevated my career and my experience,” says Anthony, crediting the Art of Nonfiction program’s deep links—rather than “weak cocktail-party ties”—that connected him to like-minded allies and funders, such as the new science-focused Sandbox Films. “A lot of that was about investing in people and investing in daring work with care and attention.”

Ironically, at the same time as some in the Art of Nonfiction cohort is concerned about financing, there’s currently an influx of equity funding for nonfiction, from longstanding sources such as Impact Partners and the Chicago Media Project to a raft of new deep-pocketed players, such as Davis Guggenheim’s Concordia Studio, which supported Garrett Bradley’s Time, and Bryn Mooser’s XTR, which invested in a startling eight Sundance films this year, including Almada’s Users and Beshir’s Faya Dayi.

Such filmmakers are thankful for the investment, but with equity financing also comes concerns that investors want to make money or break even—which can be a stretch for avant-garde nonfiction. As Green says, “With the stuff that I’m doing, you can’t give them the back-end, because it’s not an option.”

For Almada, Users was her first project to be financed with equity (in addition to grants from IDA, the Ford Foundation, Field of Vision and Chicken and Egg). While Almada says she was fortunate to keep creative control and final cut of the film, she admits, “A lot of filmmakers are giving up a lot of creative rights or ownership rights to secure their budgets.” Unfortunately, once corporate or financially motivated entities become involved in documentaries, some filmmakers have described negative experiences where “you get swallowed into the content machine,” as one filmmaker says, and what at first seems like generous support turns to frustrating clashes over content or style.

Maida Lynn, a philanthropist and investor who supported the Art of Nonfiction program and who runs Genuine Article Pictures, which has backed films by Green and Brett Story, is skeptical that equity investment suits these types of films. “There is a segment of nonfiction filmmaking which is better suited to be supported entirely by grants,” she argues. “It’s okay to acknowledge that a certain kind of film is art and doesn’t have to have commercial potential, but still has a ton of value. And that’s what philanthropy is for.”

Lynn suggests this view may not be popular in a growing sector of the entertainment business, but “to me, the equity model is very funder-focused and the grant model is filmmaker-focused. If you’re a financier, and you’re looking to recoup, it’s at the expense of the filmmaker having a sustainable career.”

Despite Lynn’s concerns, there are some hopeful signs that commercial distributors and audiences are becoming a more sustainable option for certain boundary-pushing nonfiction. Cinetic Media’s Shane Riley, who is representing Faya Dayi for sales, says, “We think there’s a healthy group of distributors and platforms that do hold those films valuable. Maybe with time and greater exposure, audiences are now interested in newness and going against the grain of the typical tropes and structures, and can appreciate a film that challenges the notion of what a documentary is.”

Kevin Iwashina, head of sales for non-scripted content at Endeavor Content and who is also representing Almada’s Users and says a distribution deal for the film will be closed within the month, agrees. “If the average person is now a fan of documentaries, then, in theory, the marketplace for this category of film has expanded. People today better relate to documentaries; they want something different and thought-provoking. We can now create excitement for consumers by way of nonfiction content.”

Indeed, there have been a number of unconventional docs that have been critical and profitable successes in the last few years, all from Art of Nonfiction beneficiaries, such as Yance Ford’s Strong Island, acquired by Netflix and nominated for an Oscar, and this year’s Oscar frontrunners, Kirsten Johnson’s Dick Johnson Is Dead, acquired by Netflix, and Garrett Bradley’s Time, which was picked up by Amazon. “Thankfully, there are distributors that are not scared or fazed by more experimental approaches to the form,” says Ford.

“I think there’s definitely been progress,” echoes Eric Hynes, a film critic and Curator of Film at the Museum of the Moving Image who was closely aligned with Art of Nonfiction, having served on a selection committee for its one-year critics fellowship. Hynes credits specifically the Art of Nonfiction program for this positive headway. “If you look at the Fellows who came out of the program, strong work came out of it. It’s not a coincidence that the films that broke through were being made by this cohort by filmmakers.”

Like film festivals such as True/False in Missouri and CPH:DOX in Copenhagen, which have continued to champion such work, giving films a prominent platform and expanding audiences for them, Hynes has seen growth with his own programming work at the Museum of the Moving Image and a monthly series he created in 2016 called New Adventures in Nonfiction. “The audience grew,” he says, “and not only in the folks showing up, but I was able to expand programming beyond that brand with week-long runs of films that could have easily been part of the series,” he adds, referring to films such as Mehrdad Oskouei’s Starless Dreams and Mila Turajlic’s The Other Side of Everything.

“But I don’t think the work is done,” he says. “I think it’s unfortunate that Art of Nonfiction isn’t continuing.”

Looking forward, Ford remains hopeful, however, that such filmmakers won’t be “considered non-traditional” at all. “The work is stunning and the storytelling is provocative and immaculate, so I always ask myself, How many more of these films have to be made for us to drop the moniker ‘experimental filmmaker’ from the description?”

Post-COVID, Ford believes there could be a moment of reckoning for both backers and filmmakers: with, on one side, foundations, institutes and traditional broadcasters rebuilding themselves and what kinds of projects they want to support, and, on the other, filmmakers branching out in ways that expand accepted forms of nonfiction, “because of the extraordinary circumstances that we’ve all been living through,” he says. “If this time hasn’t altered your notions of storytelling, maybe you missed an opportunity.”

Anthony Kaufman is a film journalist and festival programmer. He has written for The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune and Variety, and is a regular contributor to Filmmaker Magazine. He is also currently a senior programmer at the Chicago International Film Festival and Doc10.