On a very hot day earlier in June, I made my way to New York City’s Hudson River Park, one of the many new homes for this year’s Tribeca Festival. The festival, in its 20th year, presented a hybrid edition, with the in-person screenings taking place in venues in each of the five boroughs of the city. There was also an online portal, called “Tribeca At Home,” which audiences could use to bring the festival lineup home. In March 2020, the Tribeca Film Festival was one of the first festivals to shut down because of the coronavirus pandemic, and in 2021, it re-emerged in its hybrid avatar with a new name, dropping the “Film” in its title, in a bid to embrace its lineup of non-filmic storytelling through podcasts, games, virtual reality installations and television programs—definite sign of the future of all film festivals seeking to reinvent the boundaries of storytelling.

Under a migraine-inducing sun, surrounded by the usual Hudson Yard ambient sounds of ships and helicopters, ignoring the distraction and bodily discomfort, I sat amidst a socially distant, masked audience and watched four documentary shorts directed by young women of color that were made in collaboration with Tribeca Studios, Procter & Gamble and Queen Latifah’s Flavor Unit: Haimy Assefa’s Black Birth, Cai Thomas’ Change the Name, Tina Charles’ Game Changer and Arielle Knight’s A Song of Grace. All the films explore Black talent, vitality and resilience. While Assefa’s film is a video essay of her navigating pregnancy as a Black woman and forming a community to come to terms with the alarming rates of maternal mortality among women like her, Thomas’ film records the efforts of a group of Chicago middle schoolers―spurred by their inspiring Black teacher―who convince the city council to rename a park that was named after a slave owner. Game Changer celebrates the rightful place of a Black woman within the extremely sexist and racist space of the gaming industry, and A Song of Grace follows the remarkable prodigy Grace Moore, who, at 12, is one of New York Philharmonic’s youngest composers. Programmed together as “The Queen Collective,” all four shorts played on BET after the festival. The collection is not just a showcase of the immense willpower and talent of the people on screen, but also a promise of the talent the young filmmakers hold.

Jamila Wignot’s Ailey, which premiered as a part of the festival’s Juneteenth programming, honors the brilliance of choreographer Alvin Ailey. In 1958, Ailey founded the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater, which has been responsible for nurturing generations of Black artists, who, exuding boundless beauty and talent, came together to form a “choreography of the heart” that pumped lifeblood into an American dance aesthetic that was proudly and defiantly Black. “Alvin Ailey is Black, and he’s universal,” actor Cicely Tyson said at the 1988 Kennedy Center Honors program. Ailey’s body of work held in itself the history of Black movement and brought to the stage the anger and vulnerability the protestors took to the March on Washington as they put their bodies on the line.

The bodies of Chinese laborers form the center the feature documentary Ascension (directed and produced by Jessica Kingdon; produced by Kira Simon-Kennedy and Nathan Truesdell), which won the festival’s Best Documentary Feature Award. Kingdon also won the Albert Maysles Award for Best New Documentary Director. When Maya Angelou said, “Everything in the universe has rhythm, everything dances,” one is almost certain she wasn’t thinking about the robotic, monotonous rhythm of the thousands of human bodies that hold up the sky for the “Chinese Dream” of uninhibited capitalism fuelled by hyper production and commodity fetishism. The observational documentary, filmed in 51 locations, casts its eyes on several Chinese factories that manufacture pretty much everything that comprises modern life as we know it―from Trump hats to sex dolls; from blue jeans to plastic bottle caps. Within this absurd graveyard of human agency, where everyone is expected to be like everyone else, a strange music emerges from the hiss and hum of the machines that sets off the bodies of the factory workers to an unlikely dance, presented as a productive offering to the gods of consumerism.

There is a macabre mirroring of the dehumanization in the process of assembling a sex doll―rubber body parts are ironed, women put make up on disembodied heads and, with an unwavered inertness, paint nipples on the dolls. One of the few times people talk in the film are during training sessions, where Chinese professionals, especially women, are taught how to conduct themselves in “global” English-speaking settings in great detail―down to the number of teeth they should show while smiling and the ideal strength of a hug they might need to extend to a stranger. The questions that Ascension raises around human labor, the soul-crushing advent of capitalism, and what it does to human relationships and behavior, emerge from a Chinese context but find resonances in the debates around labor politics worldwide―explored with great nuance in documentaries like Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar’s American Factory. As much as Ailey is a celebration of the human body, Ascension is a deep meditation, almost a caveat, upon the extreme debasing of bodies under a system of unchecked greed and exploitation.

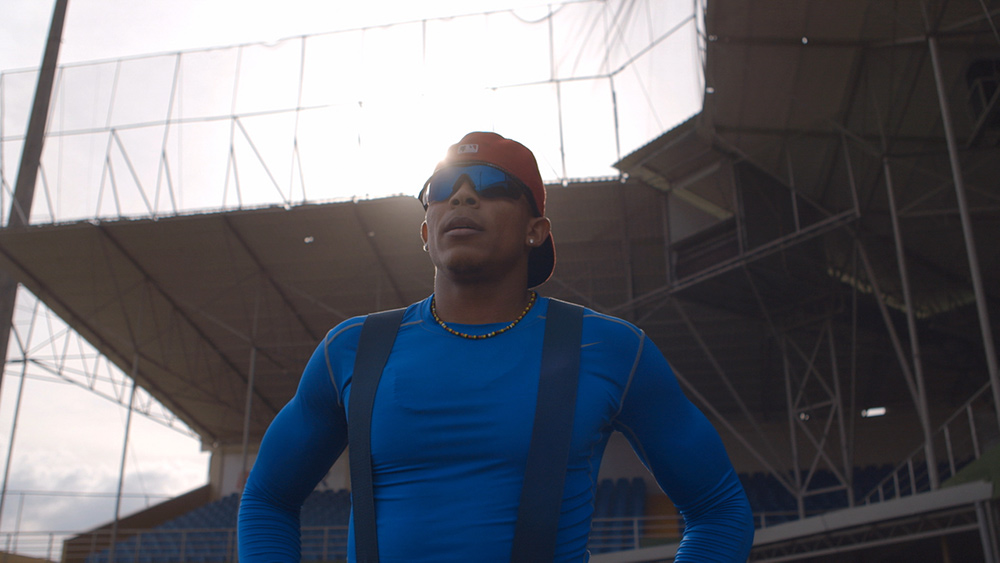

The body, again, becomes the currency for trade and commerce in Sami Khan and Michael Gassert’s The Last Out, which was meant to screen at the festival’s 2020 edition before it was forced to shut down. Thankfully, the DOC NYC-touring feature documentary about Cuban baseball players found a place in this year’s program. Since American major league teams are prohibited from recruiting Cuban players, many players like the protagonists Reynaldo “Happy” Oliveros, Victor Ernesto Baró, and Roberto Muñoz leave their families and homes and move to Costa Rica to train and audition for American teams. Under the guidance of a shady, once-arrested sports agent, Gus Dominguez, the players dream of the American life of fame and abundance―“We are all brothers here because we all have the same dream,” one of them proclaims―and then struggle to deal with the aftermath of those dreams not being met.

Within the fame and glitz of modern sports myth-making, it is often easy to lose sight of the immense physical labor that goes into the making of a sportsperson. As the players sleep on the floor and subject themselves to the exertions of extreme training routines, The Last Out empathizes with them as it uncovers the innate greed of people like Dominguez, who only see the players and their disciplined bodies as means of profiteering. Not once does the film ridicule the naivete of the young men whose entire lives have been dedicated to a dream that is rarely realized. Instead, The Last Out celebrates their resilience and dogged persistence in living out their hopes in the face of America’s anti-immigrant policies, its antagonism towards Cuba, and the ways in which these two converge and create people like Dominguez, who are so deep in the numbers game that they completely forget about the human beings and the labor behind the bodies he trades in the name of sports.

Following a year when Black and Brown bodies have been left disproportionately affected by a pandemic; when they have been subject to police brutality; and when they have turned up on the streets in protest and with demands for a just and equitable future, it is heartening to see documentary narratives that center the triumphs and sadness of these bodies and lives. Even amidst a storyscape populated by misleading AI-fuelled, deepfaked storytellers, it is the stories of these real bodies and their real labor that held up the banner of this year’s Tribeca slate, both on and offline.

Bedatri D. Choudhury is the Managing Editor of Documentary Magazine. Born and raised in India, she lives in New York City.