Raymond Depardon was a photographer before he was a filmmaker, and began his photography career during the era when theorists such as Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag were elaborating on and complicating the intellectual foundations of the form. He was influenced especially by Barthes, whom he credits with an important realization: “When I take pictures I am thinking of something else, I am not necessarily thinking of the moment.” There is a doubleness to his films, as well, evidence of a restless creative thought process that ranges far beyond concerns of fidelity to “the moment.” His films both exemplify and interrogate the journalistic impulse; discursive and dynamic institutional portraits, they also make portraiture a subject in and of itself.

Film at Lincoln Center is presenting “Raymond Depardon: Humanity in Focus,” a retrospective of recently restored and remastered films from Depardon’s prolific career as a filmmaker, which began when he was already well-established as a photographer. Born in 1942, Depardon grew up on a farm, but left home young. Having received a camera as a gift at an early age, he quickly became a photojournalistic prodigy, apprenticing in Paris from age 16 and traveling on assignment to Africa, Asia, and the Americas while still in his teens.

His photography career began contemporaneously with the direct cinema movement. Indeed, before he embarked on his parallel career as a filmmaker, he was encouraged by his mentors to familiarize himself with the work of Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker, and the observational style with which those 60s documentary pioneers, like the news agencies, navigated their new access to a world made smaller by mass media. The earliest film in the Film at Lincoln Center retrospective is A Day in the Country (1974), an embedded report on Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s 1974 presidential campaign. The project is recognizably Depardon’s answer to Primary (dir. Robert Drew, 1960), but his filmography, by now half a century long, is also a sustained and nuanced working-through and reworking-through of direct cinema’s guiding show-don’t-tell assumptions.

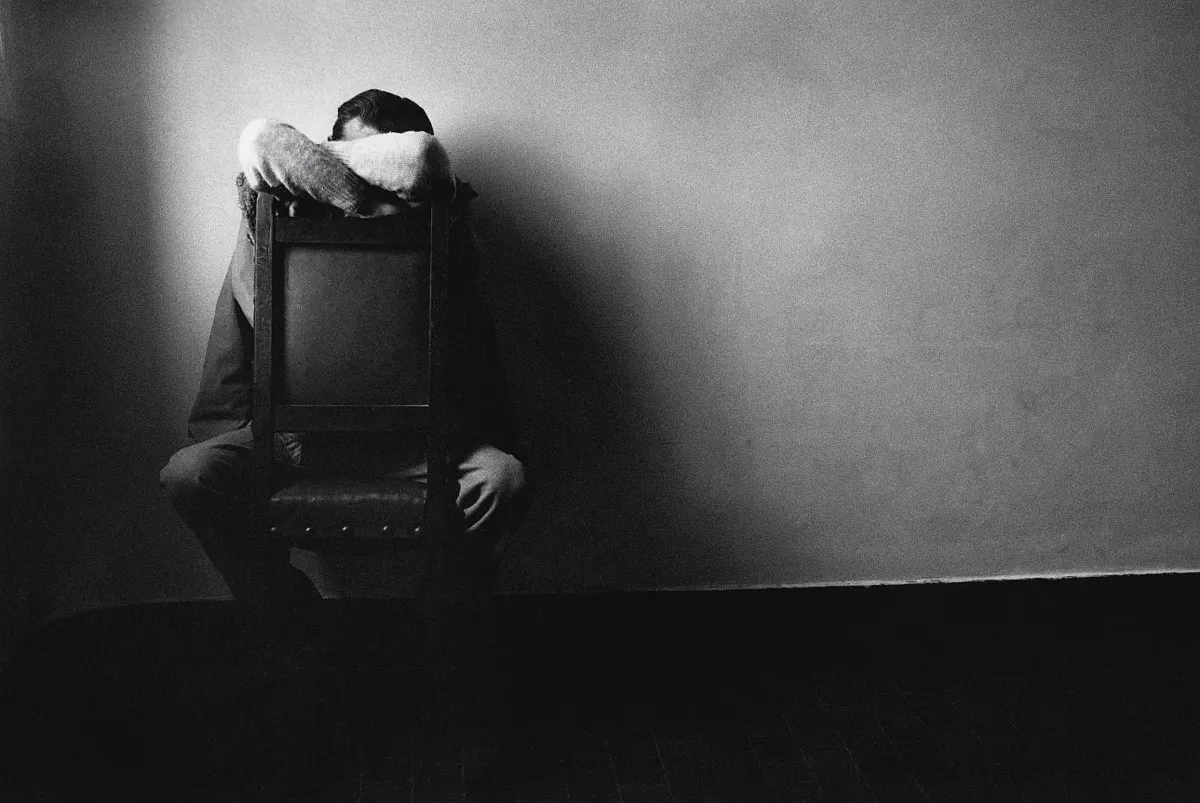

If San Clemente (1982) were a fiction film, we’d call the style reminiscent of Béla Tarr: roving long takes, in black and white as harsh as the setting, follow patients at a mental institution as they wander the white-walled corridors and wintry grounds, muttering to themselves or gesturing furiously. The handheld camera’s attention is pulled first in one direction, then another, by the impulsive surges of human activity, lingering at times on portraits of faces dulled by catatonia or animated in agitation. The mood is medieval, carnivalesque, befitting the location, on a Venetian island. Shot shortly before the hospital was scheduled to be shut down, San Clemente is a clear European heir to Titicut Follies (1967), a fly-on-the-wall portrait whose pathos implicates an overburdened, buck-passing social care infrastructure that offers its wards little more than benign condescension or neglect in the best case.

But a major difference between Depardon’s film and Frederick Wiseman’s is evident from the opening sequence. In it, a middle-aged woman in a black overcoat wanders, dazedly, into a room of dormitory-style beds; as Depardon (and his sound recordist, Sophie Ristelhueber) follow her, a nurse ushers them inside, looking directly into the camera and waving them through, before a doctor in a white lab coat makes himself first heard (“There are sick people here! It’s a disgrace!”) and then seen, escorting the skeleton crew beyond a doorway and shutting it behind them. The sound of the slamming door reverberates on the soundtrack, remonstrating against Depardon’s prying eyes.

Reporters. Les Films du Losange/Palmeraie et Désert/BPI

A Day in the Country. Photo credit: Les Films du Losange/Palmeraie et Désert/VGE

Profils paysans: L’approche. Photo credit: Les Films du Losange/Palmeraie et Désert/Canal+

This overture introduces the film’s central ethical conundrum: What agency do these “sick people,” with their contested and vacillating autonomy, possess here, and what is Depardon’s responsibility to them? And for that matter, what are the responsibilities of their caregivers, their families, their society? The transaction between doctor and patient turns out to be surprisingly analogous to the transaction between photographer and subject.

As a photographer with the agency Magnum, as he told Artforum in 2001, Depardon was “more of a witness than a creator”: “What I’m interested in today is really constructing,” he added, “because that’s a luxury. I see the photographers at Magnum: They’re all reacting, they’re doing commissions.” That reactivity is the subject of Reporters (1981). Filmed in October 1980, the film follows a handful of photographers on their assignments, from staking out a freshly divorced Princess Caroline of Monaco or wheedling an aloof young Richard Gere for pap snaps after a high-speed car chase, to scheduling trips around natural disasters and political turmoil in Africa. The film is entirely structured around whatever happened to happen that month: The bombing outside the rue Copernic synagogue, the presidential campaign of François Mitterand, the release of Godard’s Sauve qui peut (la vie). (Godard’s extemporaneous riff on the cowardice of the automatic transmission, captured here, deserves to be counted among the pick of his many, many aphorisms.)

Reporters is valuable as a time capsule, as well as a meditation on that value. In an epilogue, set at the ceremony for the annual Paris Match photo prize, awarded that November, then Paris mayor Jacques Chirac expounds to prizewinner Arnaud de Wildenberg about the new class of consumer cameras. They’re amazing—you just need to point and click. No expertise needed; anyone can do it. “Click, clack, merci Kodak.”

There is a doubleness to his films, as well, evidence of a restless creative thought process that ranges far beyond concerns of fidelity to ‘the moment.’

Tone-deaf he may have been, but Chirac had a point. Depardon needed something more than the click-clack of photojournalism. Subsequent films are portraits in the sense that photography took over from painting: the artistry lies in selecting a subject, building a relationship, and divining an essence that the final product can capture. Strong recurrent subjects stand out in the Lincoln Center series: Photography and journalism; power and politics; police and hospitals; and the home and the world, represented by the numerous films, including the Sahara-shot fictional detour Captive of the Desert (1990), originating from his reporting trips to North Africa, and by a trilogy of films made near his childhood farm. Depardon has said he felt guilt over not following in his parents’ footsteps; the struggle for continuity in the dwindling family farms of France profonde is the subject of his major work of the 2000s, the Profils paysans (2001, 2005, 2008). As Depardon’s eye became more and more selective, he returned again and again to a handful of farms in the Lozère, Ardèche, and Haute-Loire departments, recording the aging of the farmers, their daily labors in the milking shed or with the flock, and their struggle to find a young farmer to sell to in the absence of heirs.

Exemplary journalism that registers the discontented grumblings of left-behind rural traditionalists long before the Yellow Vest protests, the trilogy is also elegiac. The first film ends with a funeral oration, a closing rhetorical flourish frequently used by Wiseman to impart a sense of closure. But Depardon’s style has evolved beyond its anthropological origins. His diaristic voiceover detailing his and his family’s relationship to his subjects, and his own voice can frequently be heard from off-camera, drawing the farmers out in conversation as they sit stoically at their kitchen tables, old stoves, and cluttered shelves leaning against the old stone walls. These postcard-like compositions, fixed and frontal, have the flinty heft of a large-format photo by Walker Evans, an artist Depardon admires for his focus on rural subjects, and for the sociological depth of his images. “[T]he American school taught me,” Depardon has said, “that a message is not needed. The message is in the photograph, it is embedded.”

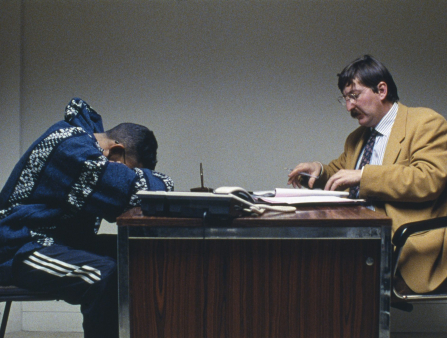

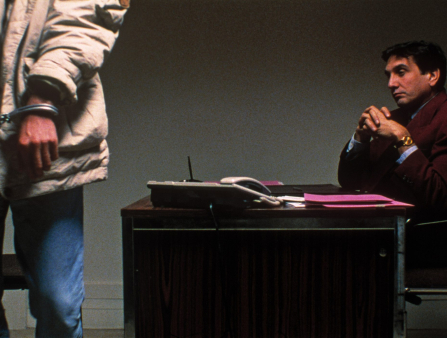

In Caught in the Acts (1994), a similarly locked-off camera likewise allows for the accumulation of a density of meaning, though the reasons for it are different. In the film, men and women accused of crimes meet with a public prosecutor, who sits opposite them at the prosecutor’s desk to hear the statements of arresting officers, witnesses, and victims. They respond, evading or defying or clamming up or breaking down. It is up to the public prosecutor to decide whether to proceed with a formal court proceeding. It was necessary to be unobtrusive when filming a criminal proceeding; each scene unfolds in a continuous two-shot (occasional jump cuts condense the encounters) with the camera in a fixed position, a few feet away from the desk, the suspect in left profile, the prosecutor in right profile. The camera becomes another aspect of the legal process, an objective public record to go along with the statements signed by the suspects at the end of each interview.

Caught in the Acts. Photo credit: Les Films du Losange/Palmeraie et Désert/Arte France Cinéma

Yet this forensic detachment is also a source of anxiety for the accused. As they state their cases to the public prosecutor—it was a slap, not a punch—their eyes dart to the camera, newly conscious of the legal weight attached to their every word, and conscious of impending judgement. In such moments, the fixed camera takes on a kind of menace, serving as an extension of state surveillance and sapping their control over their own narratives. As in the open shot of San Clemente, viewers are also implicated in the gaze. We become conscious of our own responsibilities, as well as the filmmaker’s. To justify our presence in this private, vulnerable space, we must be edified as well as amused. More than Wiseman, whose characters rarely, if ever, look into the camera, Depardon weaves a running discourse on documentary ethics into the foreground of his films.

Depardon received permission to film 86 suspects, and included 14 in the final edit. Discussing his subsequent 10th District Courts—Moments of Trials (2004), made a decade later (one of the public prosecutors from Caught in the Acts, Michèle Bernard-Requin, is the judge there), Depardon has described how carefully he’d constructed the film. When editing the film, he explained, “I made a lot of storyboards, keeping statistics—a woman, a Black woman, a Black man. [...] I really wanted to show the average French subject. I was afraid of making a movie that was only illustrating all the cliché cases.” Though, to his chagrin, he had no choice over the sexual harassment case included in the film, having filmed only one.

Caught in the Acts, showcasing a demographic cross-section with procedural clarity, also provides ample scope for irrepressible human quirk. One case we follow through the system is that of a 22-year-old apprehended in the process of hot-wiring a car, who, in conversation with a caseworker, avidly describes the fastest car she ever stole (“I adore speeding”), and then, seated across from Bernard-Requin, avers, in a hushed and chastened voice, that she has no reason to steal a car—that she doesn’t even have a driver’s license. A bracing glimpse inside the bubble of confidential privilege and an unruly flash of human interest, this sequence is one any photographer would prize as a decisive moment—and, like many others in Depardon’s filmography, its capture was enabled by a rigorous conceptual architecture.