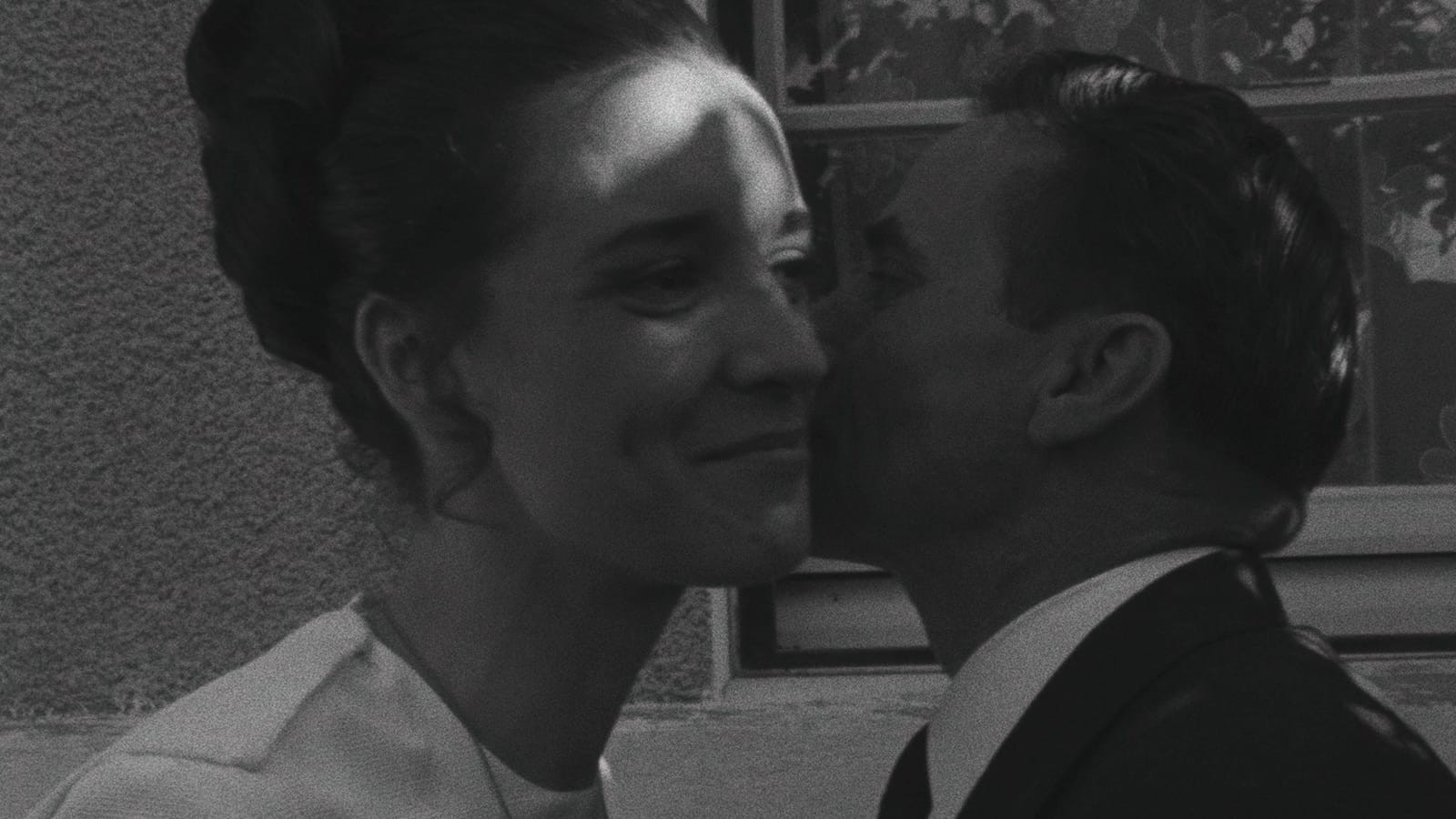

Image courtesy of Janus Films

Film at Lincoln Center’s recent retrospective, “The Dirty Stories of Jean Eustache,” brought more attention to The Mother and the Whore (1973)—the most iconic entry in Eustache’s small canon and short existence—which was recently restored after decades spent in a kind of limbo, with only the very occasional screening. And yet the retrospective is also a demonstration that the cinema of Eustache amounts to more than fiction films with documentary undertones. Perhaps the most vital strain of his work, his nonfiction films, are characterized by rich tension and reflexivity when his camera meets the real world head-on. The barbed unpredictabilities of his bohemian conservatism and his obsession with cinema not only as a medium of volatile immediacy but also as a recorder, relaying reality with a unique fidelity, invite both admiration and critique.

For Eustache, the hundreds of films that Louis Lumière shot or that he and his brother commissioned for their vast catalog mark the birth of cinema not only as a device for replicating and containing reality, like a ship in a bottle, but as a key interlinked form of personal, philosophical, and social commentary. In an interview for the May 1971 issue of La Revue de cinéma, Eustache stated, “Along with the simplification I sought in my first films, I wanted to be revolutionary, not to advance cinema, but to leap back to its origins. My aim since my first film was to return to Lumière. I’m against new techniques, which is reactionary but also revolutionary.” In Lumière actualities, the patina of an unadorned fidelity is complicated in moments where the camera operator realized that shooting an event from one angle versus another, or ending the shot at one point versus another, would transform its meaning. In Éric Rohmer's 1968 documentary Louis Lumière, archivist Henri Langlois states that their evocation of fin de siècle France is not limited to merely documenting street scenes and famous monuments and events but that the work is also filled with allusions to a range of social, artistic, and political currents, in a clear bid to suggest ways of life, perceptions, and a zeitgeist that exist beyond the frame.

Eustache was not the only filmmaker of his generation wedded to realism and repurposing forms and methods of early cinema. Eustache’s contemporary, Jacques Rivette, built a brilliant vision of realism by interweaving it with elements of experimental theater, silent cinema, and the fantastique. However, Eustache’s aesthetic was distinctive in its re-creation of many of early cinema’s indexical aims and conditions reconciled with an author’s cinema. Eustache's adoption of the foundational work of the Lumieres as a model led him to a formal approach that was raw and immersive for audiences while conjuring multifaceted and often ambiguous perspectives through a lack of annotations and a refusal to elide moments that appear confusing or contradictory.

The Virgins of Pessac

Eustache’s first documentary work began with a personal connection and an ambitious desire to put a slice of regional French history on film. The Virgin of Pessac (1968) was shot in Pessac, a commune just outside Bordeaux, an area known for its wineries (many of them church-owned) since at least the 13th century. From the late 19th century, it rapidly grew into a sizeable town and is now firmly ensconced within Bordeaux’s borders. This swiftly modernizing slice of old France was the first place Eustache called home. It served as a store of happy formative memories as he spent his preadolescence being raised by his grandmother, Odette Robert, before moving to live with his mother and her lover in the Mediterranean town of Narbonne.

Eustache had already conceived of a film that would re-create his childhood, down to “every wall section, every tree, every light pole,” but through fiction. In 1968, he was struggling to raise enough funding for what would eventually become Mes petite amoureuses (1974), so he decided to hone in on one strikingly self-conscious aspect of the town’s life and identity: La rosière de Pessac, an age-old annual pageant celebrating “the most virtuous” maiden. It was an ostensibly more chaste variation on crowning the carnival queen, suiting the town’s high-minded Catholic identity. With financing secured by Luc Moullet, Eustache set off with a crew to film the ceremony for an hour-long television broadcast. Its structure is linear and fairly process-oriented, from the initial deliberations to the final anointing of the virgin, her crowning, a parade, commemorations, and speeches. The first and most telling third part consists of the ceremony’s jury, all-male and led by the mayor, convening with a panel of “godmothers,” elderly women who present candidates and advocate for their virtues, which the jury then discuss.

Eustache—working with cinematographer Philippe Théaudière, and for the first time, editor and first assistant director Françoise Lebrun—presents the film in a matter-of-fact fashion. The panels are shot in a closely observant yet distant style and edited according to the rhythm of the on-screen back and forth, with no additional narration or music. The unadorned style, and the general “business as usual” quality of the discussions, contrast with the film’s star performer, the mayor. A smarmy figure, with his offhand, seeming but clearly rehearsed charm and exaggeratedly ebullient manner, who exudes the canned air of a host of some daytime TV fluff or a cruise ship emcee implanting a powerful impression that we are watching is not just tradition or ritual but an ensemble performance, and a highly constructed one at that. His constant light patter reduces some of the banalities or less glamorous parts of the process. He also, with less intention, exposes some of the fallacies in the ceremony with dismissive remarks toward a proposed virgin in her 40s and states that the shy winner is cute, so she will look good on camera. It’s clear that a sellable image of virtue is what truly counts.

On its own terms, The Virgin of Pessac is an achievement as a committed work of anthropology, depicting a ritual of provincial life in a country whose moving images are often stuck tethered to its capital. But it doesn’t stand alone, for in 1979, Eustache set out for Pessac once again with a crew to film that year’s ceremony for another hour-long film for television that would also be titled The Virgin of Pessac (1979).

The impetus for this second film began with an observation that Eustache mulled over while making the first Virgin of Pessac. In a speech near the film’s end, we learn of the ceremony’s centuries-old lineage, but also that the tradition was halted by the French Revolution and not resumed until 1895, the year of cinema’s birth. Eustache imagined a Lumière-style catalog, where instead of just a single film capturing the 1968 ceremony, there would be reams of moving images recording every ceremony going back to its reinception. It would provide a record of a tradition in flux, in all its ups and downs, and of the particular perspectives of the changing observers.

Eustache made one step towards this imagined project with the ’79 film and, in embarking on it, made the choice to reach for a kind of empiricism. He would attempt to shoot and shape the film as closely to the first film as possible. And yet inevitably and productively, the differences are stark.

The contrast is apparent from the first scene. Once again, the jury is mid-deliberation, but a disgruntled air clouds the proceedings. The overriding impression is that “high virtue” as an ideal may have been plentiful in the imagined past and present in ’68 but is largely absent in ’79, as the jury struggles to find a candidate that fits their criteria. It doesn’t help that the mayor in ’79 is less able to mask his and the jury’s frustrations, which peak when, after choosing that year's virgin, they find out that she’s not patiently waiting at home in beatitude but at work, so they will have to postpone the remainder of the ceremony for another day.

Both films are also political in different senses. In the older film, Eustache shows us a version of the pageant where differing views of its history are swept away so the ceremony—and the community as a whole—can maintain an undivided, uncritical sense of self. For instance, with the mention of the pageant’s long but splintered lineage in the first film, the mayor’s intention is to shore up its legitimacy by hammering home its anointed longevity and endurance in the face of wider societal change, which is occluded with the undiscussed elision. He could just easily have emphasized the ceremony’s malleability and that of culture in general. In the ’79 film, the real world impinges too much on the sacred zone of ritual to be ignored, compounding the ceremony’s brewing identity crisis with social problems such as widespread unemployment. Instead of a mayor’s speech, a more disillusioned speech is given by the town's priest. This representative of the old hierarchy and a solidly illiberal institution surprisingly describes tradition to his congregation as not hidebound and God-given but as a dialectical process, something at once both sacred and constructed, static and fluid, driven by the forces of change as much as the weight of the accumulated years.

Together, moments such as this conjure a remarkable atmosphere of ambivalence. In reference to the first film, which was shot a mere few weeks after the events of May ’68 and, therefore, in a period of intense social disruption and possibility, Moullet stated that initial responses generally mirrored their owner’s—and not necessarily Eustache’s—political proclivities. Viewers saw either a damning depiction of an archaic practice or a faithful celebration of a vestige of old France. It’s in keeping with Eustache’s contradictory, often contrarian political stance. Moullet again, in an obituary for Eustache, described it as “right-wing anarchism” maintained as an omnidirectional provocation, for it made Eustache too traditionalist and hierarchical for the left and too lax and decadent for the right. In the abovementioned La Revue de cinéma interview, Eustache positions the films in opposition to the TV news tactic of vox populi, in which multiple viewpoints are boiled down into a single, confirming, top-down view of the “common man.” In contrast, his duology treats sociality as a living, colonial animal whose human constituents bind and shed in a process that continuously changes toward an unknown future and back to a shifting past.

Numéro zéro

After completing the first The Virgin of Pessac, Eustache would give the process of another old custom a long, hard look with Le cochon (1970; co-directed with Jean-Michel Barjol) before taking his cinema into its most intimate terrain. Eustache titled the following film Numéro zéro (1971) not because it was his first film but because it was a new beginning. Its impetus was not commercial or even artistic but a gesture made on a gut feeling. Eustache was going through a deep depression when a visit to his grandmother suddenly brought about the irrepressible, emancipatory need to film and record her and her life story. With quickly-thrown-together production support and a small crew, the film took shape.

Barring a silent opening sequence, where we see Odette out shopping with the assistance of Eustache’s son, Boris, the film consists of one location: Odette sitting in a kitchenette talking about her life. She is a slightly bent and short figure who, we gradually learn, suffers from pains and infirmities. Nevertheless, in an unfussy but striking way, she has a strong bearing. She speaks with speed, precision, and a toughness that can be witty, blunt, and sorrowful. Shades covering her eyes give her a certain mystique and possible extra layer of performativity—she states she has been partially blind since her youth, but Moullet would later claim that she was feigning blindness for benefits. While her fictionalized appearance in Mes petites amoureuses depicts an image of motherly care from the eye of a child, in reality, she is convoluted like most people.

As to be expected from someone who feels she’s nearing the end of her life and is weighing up hardships, Odette’s account of her life is chiefly concerned with its difficulties. She speaks about her early days, her struggles with her poor vision, a familial outbreak of tuberculosis—which affected her and her surviving siblings’ reputations for years to come—and her mother’s death. She speaks of an abusive stepmother, an unreliable husband, and the difficulty of raising children, a couple of which she lost through poverty, familial strife, and the Second World War.

As Odette relays this slightly fragmented string of anecdotes and reflections, Eustache himself is a constant presence. He sometimes interjects to correct a statement or steer her in a different direction, or to offer her whiskey. We see him in the bottom left corner of the frame, wielding a clapper board, setting up each take. The sort of visual and verbal scaffolding that in conventional documentaries would be erased in the final cut is pointedly present here. That is, Eustache not only films his grandmother and her story but also refuses the conventional documentary impulse to invisibly sculpt by also showing the act of filming his grandmother and her story. This is true even of the film’s initial, slightly compromised version, an hour-long film released on TV in 1980 as part of a series called Grand-mères. The longer, more personal cut, Numéro zero, which ran to two hours, was shown privately to a small, selected group and then stowed away until it was unearthed, restored, and finally publicly screened in 2003. It reveals a film that runs in near-real time, emphasizing cinema’s ability to hold a moment, the intimate connection and sense of shared history between a grandmother, her grandson, and great-grandson, and a longer view, through which perhaps we can look and find our own lives reflected.

Ruairí McCann is an Irish writer and musician, Belfast born and based but raised in Sligo. He's an editor at Ultra Dogme and photogénie, and a contributing writer to aemi, MUBI Notebook, Screen Slate, Film Hub NI, and Sight & Sound.