During my 15 years in prison, numerous filmmakers and media professionals entered the facilities where I was housed with the intention of telling the stories of the people inside. Some hoped to shed light into dark spaces that our society has created; others hoped to fulfill the appetites of mainstream audiences desiring the thrill of the sensational. During my time inside, I observed an outside film crew producing a big budget film involving incarcerated people as their central participants. The directors and producers earned the trust of the incarcerated participants by approaching those relationships as friendships and making a promise of representing them in the best possible way, and with careful consideration for the stakes some people were facing. But when the film was finished, and screened inside, many of us were shocked that some characters were represented as monsters who had committed monstrous acts, and not as we all knew them to be — pillars in our community of incarcerated people.

One of my close friends, who became one of the central characters in the film, was represented in such harmful ways in the film that he subsequently received a 5-year denial at his parole hearing. The film disproportionately highlighted his crime and its impact on the victim’s family, without mentioning the decades of work my friend (who is now out of prison) had done while incarcerated to support healing and restoration for those harmed by violence. The filmmakers told participants that the film’s producers and funders thought that there wasn’t enough “drama" in the story, and that they had made narrative choices based on this feedback. Many of us felt furious and betrayed.

What seemed like a good faith attempt to tell a story about the lives of incarcerated people resulted in disastrous consequences. This story is not uncommon, as outside filmmakers all too often fall back on dominant tropes and stereotypes about prisons and the people that reside within them. It is not just the participants of these films who are directly impacted — these tendencies, when left unchecked, can lead to immense harm on a societal scale, as they have before. Historically, mainstream media representations of criminalized communities have fueled tough on crime voter sentiment, racialized fears about public safety, and cemented punitive logic in the national consciousness. This phenomenon was key to the explosion in harsh and racist sentencing laws that resulted in the mass incarceration of Black and brown communities. So in this current moment when we are seeing a surge in films about prisons, and increased public appetite for stories about incarceration, we must be instructed by the lessons of the past. We should be wary of defaulting into historical patterns in which we allow people who lack lived experience with the carceral system to dictate the discourse around incarceration and those impacted by it. We must be vigilant of all that is lost, fragmented, and distorted in that process, and the people who are harmed as a result.

The reality is that most who are directly impacted by incarceration are not positioned in a way where we have access to telling our own stories. They are most often told by outsiders who lack an understanding of the nuanced but very real stakes for incarcerated people who go public with their stories, lacking regard or commitment to their safety and liberation, while being able to position themselves as experts or neutral translators nonetheless. Their commitment is to the story, not to the people.

—

I learned filmmaking in 2018 when I got to San Quentin and eventually began leading a media project called FirstWatch (now ForwardThis Productions). We were creating short films and videos, not only about the realities of prison, but also about our boundless inner lives and the communities we were creating within and beyond walls. The film equipment, which was donated by outside organizations and sponsors, allowed us to communicate through this medium with the outside world, as the videos were permitted to leave the prison and live on certain media platforms. However, even though we were working and growing as filmmakers inside, producing works for the prison and outside organizations, we were never compensated monetarily for our labor.

At FirstWatch, we were committed to empowering directly-impacted people to tell our own stories authentically as a path to reclaiming media representation and seeding political change. Since we knew intimately that one huge function of prisons is to make people invisible, if people could see us the way we saw each other, if we could see ourselves in different ways, there was a possibility for transformation — both personal and political. Though we weren’t compensated or otherwise given the respect of professional filmmakers, we could see the impact of our work within our community, as the films and videos we created screened in all 36 of California’s prisons. I would regularly hear from people coming to San Quentin from other prisons about how inspiring and healing it was to see incarcerated people represented on the screen in ways that they had never seen before.

All of our work was grounded in community — we understood that everything that we did flowed from our political commitments with our fellow incarcerated people across the nation. With an awareness of the privilege and unique platform we had making films from inside of a prison, we stood in direct opposition to ideology that says that Black and Brown communities are inherently violent and should be caged. This commitment to community-based political organizing challenges the institutional power of the media, which is overrepresented by white media professionals and perpetuates racist, harmful narratives about communities impacted by incarceration while upholding the power and authority of law enforcement institutions. In contrast, narrative repair replaces harmful tropes of incarcerated people with narratives that uplift and inspire impacted-people to resist, heal, and build solidarity with each other. By creating new identities based on collective struggle and care, systems-impacted communities can begin to heal the ways they’ve internalized brokenness.

After coming home in October of 2020, I set out to direct and produce my first film, What These Walls Won’t Hold, about my experience living through the COVID-19 pandemic in prison and the intimacies formed between people through political organizing. The production of the film felt like an important place to reconsider and undo all of the unscrupulous practices that I had witnessed from the filmmakers who had extracted stories from inside. All of the participants in the film are my dear friends. It was vital to me that the film be a communal space where people felt like their stories could be expressed accurately, and with care. The participants have producer credits and were also compensated for their work on the film, unlike my time working as a filmmaker inside of San Quentin, when we were never paid for our work.

In spite of all of the work I would do to create an equitable environment working across prison walls, I would ultimately see the limitations that the prison would put on these relationships. The distance between myself and my loved ones inside, whom I was working on the film with, wasn’t just physical, but also about status, access, privilege, and power. The moment I had walked out of that place and into the free world, I inhabited a completely different social position, away from the daily violence, urgency, inhumane conditions, and high-stakes of prison life. As much as I sought to resist this dynamic, to relate to my dear friends in the same ways that had brought us so close together, in work and in personal growth, the inequities in the material conditions of our existences were a reality that I couldn't avoid.

So in light of these inevitable power dynamics, how can we work towards creating new models of ethical partnerships in our filmmaking process? Inspired by the Documentary Accountability Working Group framework and adapting it for the particulars of prison documentaries, here are some key tenets I consider:

- Be Accountable: Filmmakers should be accountable to the participants in their films, and cognizant of the extreme stakes that are present for incarcerated people when they decide to share their stories. Their freedom and safety is at stake, and there should be a commitment to protecting those things.

- Consult with directly impacted people: It is critical to receive input from consultants with lived experience who exist outside of the filmmaker-subject relationship. For film to be useful for social movements that work in resistance to the Prison Industrial Complex, they must be led, or in deep collaboration with, impacted people and political organizers.

- Employ systems-based storytelling: What is often missing in character-driven storytelling is a critical analysis of the structures that shape a person’s life and decisions — in essence, seeing the trees but not the forest.

- Be transparent in your relationships: Practice honesty with your protagonists, supporters and funders and be clear about your intentions for making the film — there is a higher standard for transparency when it comes to the people participating in your film, especially if they are incarcerated. Be transparent about your decision-making and what guides it (do your participants have any say or is it all yours?). Be transparent about who your main audience is and what kind of impact the film may have on a person's life.

- Acknowledge and share power: You hold the power to shape and interpret stories — your own and those of others. A values-based filmmaking practice requires an acknowledgement and deep examination of your lens, preconceptions, and the power you hold as a filmmaker. Consider what you have to gain and lose as a filmmaker, and whether or not that is out of balance with your participants, and work to close those gaps. Are you the best person to tell this story/make this film?

- Respect the dignity and agency of the people in your film: Build informed consent in your interactions with participants, giving people agency to represent their story in a way that honors them.

- Understand that your audience also includes impacted communities: with roughly 2 million people currently in carceral facilities across the US, plus their loved ones and communities, an outsized population has a stake in these stories and should be accounted for. Consider the ways that your work may be read, interpreted and experienced by the people who have intimate knowledge of the story. Be clear about who your intended audience is, and what information you can add to their already established knowledge. Additionally, be responsible about the ways that your film could trigger or traumatize those audience members who have more experience with the film’s content.

Understanding the complicated power dynamics of collaboration across prison walls means not only being in deep relationships with participants, but also constantly asking the following questions: How can I make this exchange reciprocal? How can I align the intentions of the film with the needs of my participants on both a personal and political level? Why am I telling this story?

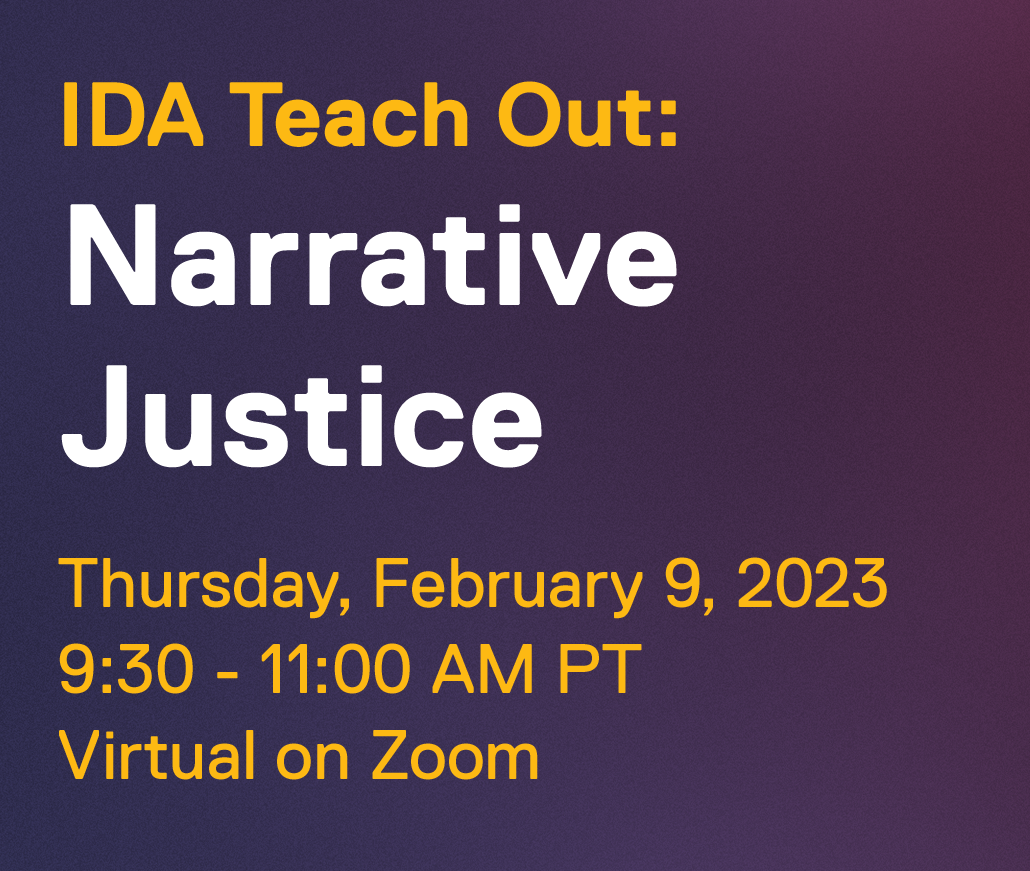

How do you make a film about the experience of incarceration? Given the complexities of consent and power, what are the ethics this work requires? What is an ethic of narrative reparation? On Thursday, Februrary 9, 2023, at 9:30am PT, join filmmaker/activist Adamu Chan and a panel of award-winning filmmakers Brett Story and Jasmín Mara Lopez, and co-host and co-producer of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast “Ear Hustle” Rahsaan Thomas, for an IDA Teach Out: Narrative Justice.

Adamu Chan is a filmmaker, writer, and community organizer from the Bay Area who was incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison during one of the largest COVID-19 outbreaks in the country.