"You never forget your first time seeing a whale," director Joshua Zeman says in The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52. His was as a kid working on a sailing ship. But the impetus behind this documentary came years later, after he read about a solitary whale that couldn’t communicate because his call was at a different frequency from every other whale: 52 hertz. Dubbed 52, he’d been roaming the ocean for decades, his song unanswered.

Though heard on hydrophones, 52 had never been visually spotted by scientists. Zeman decided to try. Through Kickstarter, he raised enough money for a seven-day expedition with a crack team of whale biologists. "That’s very much part of ethos of the film," Zeman says of the Kickstarter campaign. "This is not a slick, glossy NatGeo or IMAX film. We took all our scrappy, independent-film skills and applied them to that huge IMAX–NatGeo setting."

The Loneliest Whale follows this expedition and also weaves in segments on our historical fascination with whales, 52’s discovery in 1989, whale songs, and how whales are now being threatened by underwater noise pollution.

The following four-minute scene captures a turning point in the expedition. After three futile days, the scientists finally manage to tag a blue whale with a tracking device. Their hope is that other whales might lead them to 52, since he’s likely swimming with a pod in search of food. Cinematically, the scene utilized two Canons, a drone, a GoPro, and a "whale cam." Dramatically, it shows everyone’s relief that this impossible quest just might work.

The Scene

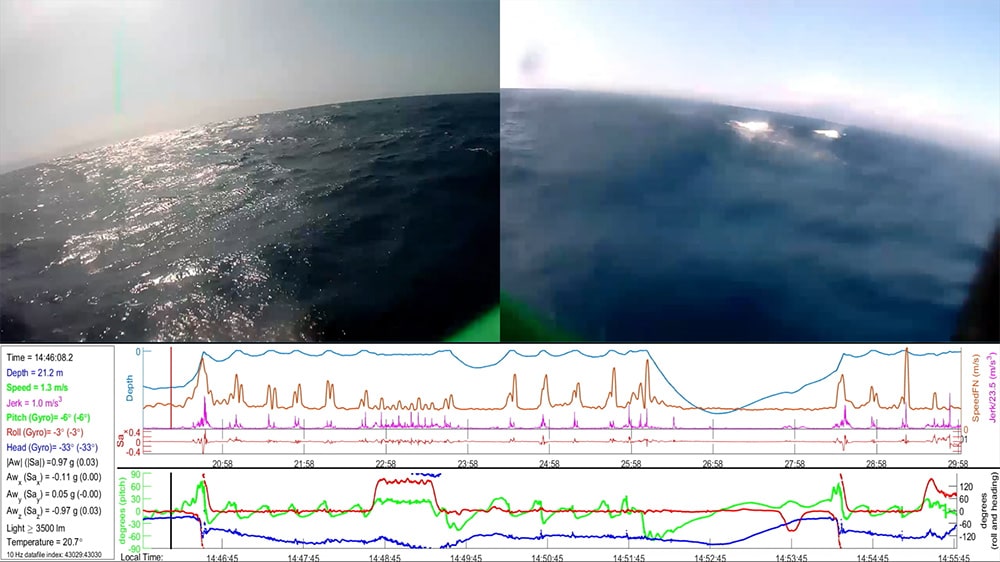

It’s day four and the team sets out again to tag a whale. Custom-designed by the scientists, these tags contain two miniature cameras pointed front and back, plus data collection devices that record everything from the whale’s speed and depth to water temperature and light.

The scene starts below deck in the research vessel, where marine biologists are prepping their instruments. One throws overboard a sonabuoy—an acoustic device once deployed by the Navy to detect submarines and now used by marine scientists to listen to whales. The camera grabs a close-up of a monitor. A blue whale is nearby.

As the music builds, the scene quickly cuts between the main boat and the speedy RHIB (rigid hull inflatable boat), which carries the tagging scientists. On the research vessel, the camera has moved up to the crow’s nest, where spotters with binoculars are trying to pinpoint the whale; they then provide play-by-play commentary as they watch the chase. These shots alternate with the inflatable’s perspective, captured by a cameraperson at its stern. The research biologist piloting the RHIB wears a helmet-mounted GoPro, as does the scientist on the gangplank, who wields a 20-foot pole with the tag.

Their first attempt fails. The timing is off. But someone in the crow’s nest spots a second whale. Cut to the drone, which pivots from the inflatable to this second whale. They try again. At a critical moment, we cut to the GoPro, which gives an unobstructed view of the gangplank and whale. The scientist thrusts just as the whale arches above the surface. This time he scores.

We immediately cut to the whale cam. The pulsing music stops, replaced by the quiet gurgle of underwater. We see the whale’s back moving through dappled sunlight, then break surface. We hear a voice laconically report over the walkie-talkie, "So, we did get a good deployment there."

The next sequence is a joyous montage of tag deployments, accompanied by ’70s band Pablo Cruise’s "Love Will Find a Way," which yacht-rock fan Captain Davy blasts from the bridge.

The Gear

"There’s not a lot of high-tech gear, because once we leave the port, there’s no going back," the director says. Reliability was the name of the game. That’s why they chose a trusty workhorse, Canon EOS C300 Mark I, as their main camera. (The film was eight years in the making, and this expedition occurred in October 2015, so all gear has gone through multiple iterations since then.)

In this scene, cinematographer Alan Jacobsen was on the research vessel operating the C300, relying mostly on a Canon 17–55mm. "That’s a great range for vérité scenes where there’s a couple of people talking, following shots, moving around," he says. "In such a small place, we needed a nice wide lens to fit people in."

Up in the crow’s nest, he switched to a long-range zoom, Canon 70–200mm, capturing shots of the RHIB on the long end of the lens. Holding focus at 200mm on water wasn’t easy. "I’d considered bringing a stabilizing system onto the boat. I decided against it because it was another thing to break," Jacobsen says. "I was really glad we didn’t have any kind of hard-mount stabilizer, like in the bow of the ship, because 60 percent of the time it would have been facing the wrong way. The fact we did everything handheld was a real asset because we could respond quickly."

Meanwhile, B-camera operator Bryce Groark had a Canon XF305 camcorder in the RHIB. The latter is another dependable workhorse, being one integrated piece with a 29–527mm zoom suited for both wides and long-lens shots. The camcorder is stabilized and has three ND filters built in. It’s perfect for speeding through choppy waters without lens changes.

The drone operators were aerial cinematographer Bennett Cerf of Strato Aerial and drone pilot Drew Roberts of Wild Rabbit Aerial. Their shots captured the magnitude and majesty of the sea, but the drones also served the scientists well, spotting and documenting whales from the air.

They brought two drones. One was a heavy lifter, DJI’s S1000, which carried a Panasonic Lumix GH4 4K mirrorless camera. Mounted with a Ricoh 12mm or 25mm prime lens, "this bigger drone had better quality footage, but we couldn’t really control the camera remotely," says Cerf. "We could just turn it on and off. So when we knew we had something that was high quality, we would send the heavy-lifter out. If we were just doing random searching or whatnot, the smaller drone was convenient."

This smaller drone was a DJI Inspire 1, the company’s original all-in-one package. In this scene, we see it take off from the deck, then there’s a quick shot from the drone looking back at Cerf and Roberts. Later, we see it spot the second whale, just visible beneath the water’s surface.

The Shoot

"Shooting on water is like trying to nail Jello to a wall," says Zeman. Jacobsen agrees: "It’s constant reaction."

That’s why the cinematographer was happy to forgo a fixed-mount stabilizer. Moreover, the aesthetic of this film was not to have things too smooth and slick. "We wanted the audience to feel the energy of the chase; we wanted it to feel a little rough," Jacobsen says. Regarding shots in the crow’s nest, where his stomach muscles were the main stabilizer, he says, "I ended up liking how that long lens was bucking around, reacting to the ocean. It showed the energy of that sea: the wind and water and forces at work."

But if you’re staring into a small drone monitor when a boat is bucking, penance must be paid. "I got sick," Cerf admits. "But everybody kind of got sick too."

Another challenge was covering a scene that you could see only half of. When Jacobsen was on the research vessel, Goark might have been out of radio range on the RHIB. "I was on the ship shooting one half of what I hoped was a scene that was happening on the other end," Jacobsen says. "I told Bryce, 'Even if something’s not dramatically happening on your boat, remember that something might be happening on our ship. Cover enough so that if we have to cut back and forth, we can.'"

In any case, Goark was too busy holding the camera with both hands to handle a walkie-talkie. Once the RHIB got going, it was so rough that Goark had to be literally strapped to a padded metal armature in the stern. Meanwhile, says Jacobsen, "Our sound man [Dafydd Cooksey] was sitting in the bottom of the RHIB in a puddle of water for hours on end, trying to keep his equipment dry."

The director’s favorite shot in the whole film is that thrilling, quiet underwater moment after the whale is tagged. "I love it when filmmaking and science mix," Zeman says of the whale cam footage. "The dailies, if you will, were just so incredible because something new would happen all the time. You could see the whale opening his mouth to feed, you could tell when it was calling, you could see little crabs going across the body. You could literally watch this stuff all day long."

"Suddenly we’re leaving the realm of man and descending into this unknown world of the whale," Jacobsen adds. "So much hubbub above ground, then once that tag is on and you descend with the animal, there’s a whole other world."

The Loneliest Whale opened in theaters on July 9 through Bleecker Street Media, and premieres online on July 16.

Editor's Note: In the closing four paragraphs, Bryce Groark and Bennett Cerf’s names got transposed, so we rectified that error. We have also credited the sound recordist, Dafydd Cooksey. Documentary apologizes for the errors.

Patricia Thomson is a longtime film journalist and a contributing writer for American Cinematographer.