Fifty years ago, an uprising at a prison facility in upstate New York changed the course of history. And yet today the word "Attica" might more easily bring to mind Al Pacino’s infamous line from Dog Day Afternoon. Which is a shame—although also perhaps inevitable. For what turned out to be the largest prison rebellion in US history—culminating in "the deadliest violence Americans had inflicted on each other in a single day since the Civil War"—was also a media spectacle that played out for five days across TV screens around the world.

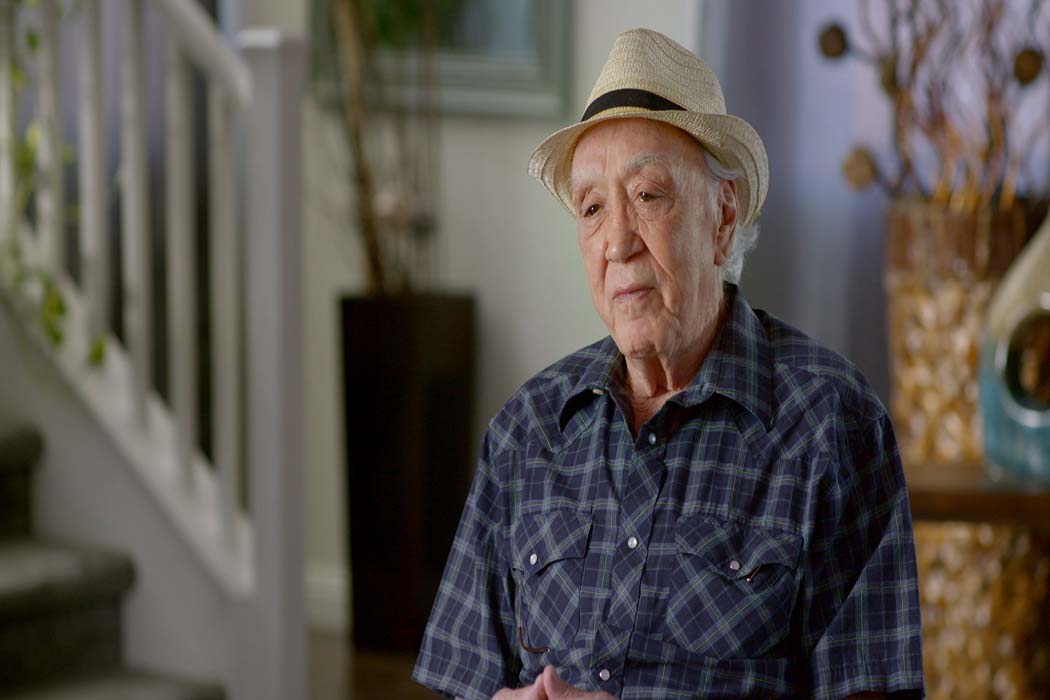

But for the incarcerated—and all the families on the outside—who experienced the cataclysmic event in real time, "Attica" is not a meme. And one of those formerly imprisoned men is Al Victory, who was only 27 in September 1971. Shot twice, then later beaten and thrown down a set of stairs (and ultimately threatened in an attempt to get him to cooperate with authorities and "lie against fellow inmates"), Victory has for decades been on a righteous mission to ensure that the lessons of Attica not be relegated to some dustbin of fictional Hollywood history. He sees parallels to the protests sparked in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, as well as to today’s calls for racial justice and police accountability. And notably, he’s also one of the few white faces to appear in Stanley Nelson and Traci A. Curry’s Attica, a masterful revisitation of the uprising and its aftermath. The film premieres November 6 on Showtime.

Documentary is thrilled Victory found time to chat with us about the doc, what’s changed over the past half-century and what has not—and to agree to take the spotlight as our November Doc Star of the Month.

DOCUMENTARY: So how exactly did you get involved in this project—and why?

AL VICTORY: Well, I’ve been involved with Attica’s aftermath since the day it happened. And I’ve struggled along the way. So Attica to me was a major impact on my life, and it continues to be. I was always available—and always will be as long as I’m able—to try to make some difference in regard to criminal justice in America.

The bottom line is, I felt an obligation to tell the story, to let people know. I don’t know how much of an impact it’s gonna have, but I certainly hope it somehow influences the mind of folks that are gonna be seeing it. To understand that at some point justice and truth may be even more important than life itself.

So that’s how I got involved. I was available and folks reached out to me and asked if I would do it.

D: Why did the filmmaking team reach out to you specifically?

AV: I have been putting on every year—almost every year, when I could afford it—a memorial for the Attica Brothers and everybody for that day. So I was pretty well known. They gave Traci my number and she called. Then they set up an appointment to videotape me.

D: So you immediately signed on? Was it at all traumatizing—or maybe liberating—to revisit such a personal (and political) story, though?

AV: I know it sounds corny, how something 50 years ago can still continue to affect me. But it does. Like I said, every year I used to put on a memorial for the Attica event and for the Brothers. We’d get together and remember, and talk and share a meal. This was not something that you walk away from and say, Okay, well, bad day. This was a tragedy that didn’t have to happen.

D: What was it like discussing this all on camera, though?

AV: Embarrassingly, I was crying most of the time. Memories of friends who were lost, and friends who have passed away since then. It’s a thing that you never forget, you never will, and you never want to. Even though it was a horror show.

It’s affected me all my life. The interview in and of itself caused me to relive that, which I do anyway. Especially once a year. But to some degree it was liberating to be able to share it. Except that I was a little embarrassed because I was kind of weepy when I was talking about different people who are no longer with me, with us.

It was only when they refused to even talk to us, to try to understand what we were living through, that we had no choice.

D: It seems an event like that would leave someone with post-traumatic stress, like being in a war zone.

AV: It was a war zone for real. The trouble is that the only ones that had the guns and the ammunition were the Nazis on the wall, shooting at unarmed people who were desperately trying to make their lives a little bit better. Just trying to shape some humanity before they wiped it out of all of us. That’s what we were trying to do, even prior to any of this, to the rebellion. It was only when they refused to even talk to us, to try to understand what we were living through, that we had no choice.

D: I think we got that aspect from the film.

AV: It’s why I hold Stanley Nelson and Traci Curry in such high esteem. They were able to grasp why it was so important to tell the story as they did, and truthfully and fairly.

D: So what’s been your overall reaction to the film? Are there interviews or scenes you wish had made it into the final cut? Maybe anything you’re uncomfortable with being shown?

AV: I think it’s a revelation. A lot of the things that they were able to find and put into the documentary were things that I had never seen before—certainly not from that perspective. I was living it inside and suffering the consequences of it, but they brought to life so much information and so much emotion in me. It was a genius effort on their part. And I hope the whole world has an opportunity to see the film. Not so much for the Attica Brothers. Just so they can see the raw hatred, the fascism, the white supremacy and ugliness that we have to get over. I hope to God that this effort is appreciated and understood by the public, because we have to stop this. We have to change the world some way.

D: So did the interviews with the families and the people on the outside give you a different understanding of anything? How do you feel when you see all the other angles?

AV: Well, we all shared in the traumatic experience, including the families and the guards and others. Do I understand their positions and their feelings? Of course I do. The guards, the state troopers who murdered and maimed people...I mean, they had the gall to put up a statue in front of Attica about how we lost these people, these guards. They killed them! And they probably picked some of them out because they spoke on TV saying that the inmates had reasonable demands. They were all killed by the other guards!

So of course I feel bad for the families of the folks that died—all the families. But I don’t feel anything but shame that those guards who did this and didn’t come out and say, "Listen, what did we do? How can we live this way?" They know what they did.

But more than that, [John] Edland, the coroner, and [Malcolm] Bell, the prosecutor who told the truth about how this was all about putting the blame on the inmates—those guys are my heroes. They refused to be cowed and intimidated by the people who were threatening to kill them if they told the truth. None of this story would have happened if they didn’t have the courage to say, No, I’m not gonna let you do this because it’s a lie.

D: So you think that the murders of the guards was backlash for them speaking to the press?

AV: Yeah, that was backlash. Because many of the guards, especially the ones that were killed, got in front of TV cameras and said, "Listen, please, [Governor] Rockefeller, come out and work this out and let’s all go home happy and without problems." And also the inmates that were leaders and in front of the TV cameras saying, "Listen, we need help here. Please listen to what we’re saying because this is a desperate situation we’re in."

The world got to see what it looked like to be a prisoner who was being literally stripped of his humanity, just trying to hold onto as much of it as he could.

D: So does this affect how you deal with the media, and maybe even with documentary filmmakers? I mean, do you feel ambivalent about the media since people were killed because of press coverage?

AV: No, not at all. Things don’t change unless you speak out. Though originally, right after the murders and the massacre, they just took the words of Rockefeller’s promo people, trying to blame everything on the inmates. The whole world thought of us as monsters after that.

So when the media came in, it was a sensational moment because it had never happened before. The world got to see what it looked like to be a prisoner who was being literally stripped of his humanity, just trying to hold onto as much of it as he could. And yes, people were jumping in front of the TV because this was a moment when maybe somebody would hear us. It was a way to reach out from the desperate places that we were in. For that I praise the media.

D: But were you aware at the time that you were having an impact—or were you just in the moment?

AV: No, we knew we were having an impact because we had observers in there—wonderful, heroic folks who came into the yard. I wouldn’t go into the yard if I was a civilian and didn’t know any better. I would be scared to death. And I’m sure they were too. Even the media folks who came in with cameras. But they did it. And for the first time they let the world know that we were willing to die rather than continue to lose our souls, what was left of our humanity, after being placed in prisons that were designed to literally torture you.

And also that we were being guarded by white supremacists. And we were all mostly Black and [Hispanic] inmates, or poor white inmates. And this was our one chance. You see the guy that killed George Floyd? He was there in Attica. The same guy. Maybe different face, different name, but he was there throughout Attica. Killing, torturing.

D: So do you feel like the uprising truly had an impact then? Because we still have George Floyd today.

AV: I think it did. For the first time prisoners were shown to have been telling the truth. We didn’t kill anybody. And it was for the first time in history that the world understood what it was like to be in a prison like that, guarded by white supremacists and/or slave masters. We were the slaves. Didn’t matter white, Black or [Hispanic].

D: So what has happened within the prison system that you see as positive change? Are there more people of color working as guards? Does that really make a difference within a broken system?

AV: Several years after the Attica rebellion and the Attica wakeup to America—to the world, on some level—the system really did change. Russell Oswald [head of the state's prison system] stayed there for a while, and pretty much all the demands that we had made—well, other than amnesty—

D: And flying to Cuba.

AV: Yeah, other than all of that stuff. But for several years they started call-ins—you could make calls to your home, you could have real visits. The guards became aware, at least to some degree, that they had to treat us like people because we actually demanded it. We said, No, we won’t let you do that to us again.

However, after several years the bad guys got in again and they started—one step at a time, every six months—pulling back, ending, and/or changing the improvements that we had gained as a result of the rebellion.

But we did cause a lot of change, for the New York system anyway. You had trailer visits where you could visit with your family. I mean, they really understood that they had to do something; they couldn’t keep running their system the way they had. So yeah, I’m proud of what we tried to do and I’m proud of what we did, even though it was a horrific event. And I’m proud that we had some major effects on the lives of prisoners going forward for maybe 10 years. Until the—and I hate to put it this way, but until the fascists and white supremacists got back in control.

D: Well, speaking of the whole white supremacy aspect, you’re white. So do you feel that you have more of a platform to speak on these things? Do you feel people in power listen to you more than they would to a Black prisoner? How do you feel about that?

AV: How do I feel about that? I don’t know. I’ve never really thought of it from that perspective. When I discuss Attica I talk from just my personal experience, my personal observations. And my personal embarrassment that as a white person there are other whites that are more privileged, that have acquired their land and their wealth and don’t want anybody else to even have a chance at life.

But because I’m white they’ll listen to me quicker than they will a Black person? Uh, possible. Probably.

Whites literally have had hundreds of years of building their nest egg and their legacies and their trust funds and foundations—and everybody else is struggling for pennies, just killing each other over food and some semblance of humanity.

D: I just think back to the idea that racism isn’t really a Black person’s problem in the US. White people are the cause, so they need to speak out on it.

AV: Whites literally have had hundreds of years of building their nest egg and their legacies and their trust funds and foundations—and everybody else is struggling for pennies, just killing each other over food and some semblance of humanity. You have it all. Share it. Stop it! This is obscene. And when you say it’s a white problem rather than a Black problem, it’s not. It’s a human problem.

Until we can live on earth together—and protect earth and protect each other—and find a way to make sure that it’s not just about us and everybody else is on their own…Really, we just have an obligation to each other.

D: You do see that in the message of the film. There’s such a diversity of voices in Attica that it really gets to that humanity aspect, where everyone is sharing in this collective trauma.

AV: That’s the genius of Stanley Nelson and Traci Curry. They were able to take all of that, explain what occurred back then—and why, 50 years later, it’s still important that we all understand it. Attica is all of us. Every one of us. Our children, our sisters, our brothers. Attica means, Fight back against injustice, even if it kills you.

Lauren Wissot is a film critic and journalist, filmmaker and programmer, and a contributing editor at both Filmmaker magazine and Documentary magazine. She's served as the director of programming at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival and the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival, and has written for Salon, Bitch, The Rumpus and Hammer to Nail.