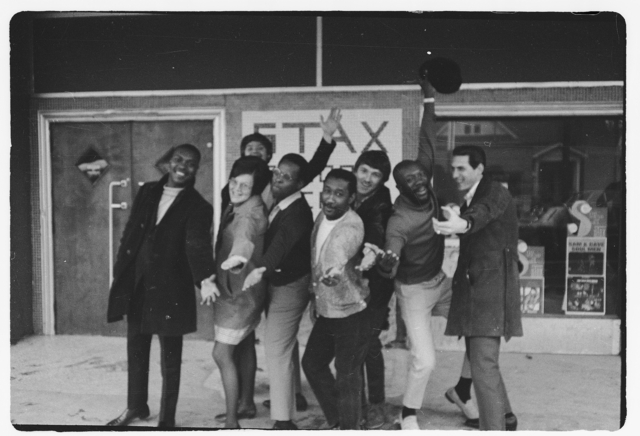

(L to R) Charles Hopkins, Asher Rodriguez, Sophia Dilley, Quíle Gomez, and Wesley Adams. Courtesy of Concord Originals

Making a Production is Documentary’s strand of in-depth profiles featuring production companies that make critically-acclaimed nonfiction film and media in innovative ways. These pieces probe the creative decisions, financial structures, and talent development that sustain their work—revealing both infrastructural challenges and industry opportunities that exist for documentarians.

In the final episode of the four-part, Emmy-nominated documentary series Stax: Soulsville U.S.A. (2024), Al Bell, former co-owner of the legendary Stax Records, discusses how a chance meeting with Winthrop Rockefeller as a young man opened his eyes to “the rules of the game in America.” Bell specifically refers to the world of high finance, and how when a small business becomes prominent enough, it inevitably starts to infringe on the market share of large corporations. For these enormous companies to survive, they must either subsume their growing competitors or destroy them. “The big fish must eat the little fish,” Bell solemnly notes.

Directed by Jamila Wignot and executive produced by Ezra Edelman—two filmmakers acutely attuned to how Black figures refract the eras in which they arise—the series contextualizes the influential, integrated Memphis record label, which produced artists like Otis Redding and Issac Hayes, in the fraught history of American race relations. Stax addresses the myriad ways politics informs art throughout the label’s brief history, including and especially the rapid development of corporate capitalism. Manipulative tactics and business naivete ultimately conspired to push a significant engine for Black expression into bankruptcy.

It’s unavoidably ironic that of the six companies that produced Stax, three are the “big fish” that currently own the label’s music following its slow demise. They are as follows: Polygram Entertainment, a division of Universal Music Group; Warner Music Group’s Warner Music Entertainment, owned by Warner Bros. Discovery, which once absorbed Atlantic Records, the previous owner of the vast majority of the Stax catalog; and Concord Originals, the “narrative content creation division” of Concord, an independent company whose focus is managing music rights. In 2004, Concord acquired Fantasy Records, which previously acquired the post-1968 Stax catalog in 1977, and formally relaunched the Stax brand in 2007. They have licensed the music ever since.

Although any project about Stax Records or featuring their music would legally and logistically require Concord to be involved, Stax: Soulsville U.S.A. is unique in that it actually originated from the company itself. Officially launched in 2021, Concord Originals produces and develops projects based upon the million copyrights the company owns and represents, such as the music of Creedence Clearwater Revival (Travelin’ Band: Creedence Clearwater Revival at the Royal Albert Hall, 2022), Rodgers & Hammerstein (My Favorite Things: The Rodgers & Hammerstein 80th Anniversary Concert, 2024), and Cyndi Lauper (Cyndi Lauper: Let the Canary Sing, 2023).

Though the process of choosing potential projects from the company’s enormous library generally entails input from multiple departments, Concord Originals’ Executive Vice President Sophia Dilley and her team are primarily responsible for pulling the trigger on bringing their music to the small and silver screen. Dilley had been working in the development and production space for years before being recruited by Concord. In 2018, when the company was building out its various branches—recorded music, publishing, and theatrical—she had a meeting with then-CEO Scott Pascucci about different ways of enriching their overall slate.

“At the time, Concord had just acquired Rodgers & Hammerstein’s catalog and it came with all these film and TV rights,” Dilley remembers. “Scott told me that they were thinking about creating a division that supports them. Essentially, how can we look at the rights that we’re acquiring and find new ways to bring them to life?”

For Dilley, this was something of a dream come true. She always had a passion for film and music, dating back to college where she studied film production and played piano in an orchestra and jazz band. After working for director Peter Berg (Friday Night Lights) during her sophomore year, she realized his success was partly because he was involved in so many different aspects of the business beyond the creative side. She eventually worked her way up the ladder at the independent finance company Route One to become vice president of development and production.

By the time she was hired to head up film and TV development at Concord, Dilley felt like her production experience and creative interests were tailor-made for the newly designed position. “When I came on board,” she says, “the idea was to adopt a studio approach to these different types of rights at our disposal. It was a role that brought all the things that I love together: storytelling across the stage, music, film, and TV.”

As EVP of Concord Originals, Dilley oversees an intimate five-person team that actively works in the development space. They have multiple projects in the pipeline on both the scripted and unscripted side, including a documentary on Billy Preston currently touring festivals and an “elevated genre film” inspired by Delta blues musician Robert Johnson. At a time when music has become the most popular intellectual property this side of comic books, Concord is poised to become a major player in the film industry simply by being the big fish in their own self-generated pool of copyrights.

***

In 2024, music documentaries were ubiquitous on streaming services. Most of these films revolve around the life and career of a particular artist. Kings From Queens: The Run DMC Story (Peacock); Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple (MAX); Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story (Hulu); The Tragically Hip: No Dress Rehearsal (Amazon Prime); The Beach Boys (Disney+); and In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon (MGM+) are just some of the offerings available to watch depending on a person’s subscription inventory. Others tackle a specific subject and use it as a lens to view a cultural moment or a sociopolitical ill, like Netflix’s The Greatest Night in Pop, which chronicles the making of “We Are The World,” or Paramount+’s As We Speak: Rap Music On Trial, an exploration of how the criminal justice system weaponizes rap lyrics.

Active artist/estate participation in these types of retrospective portraits has become a key element in legacy construction. Oftentimes, they renew interest in an artist’s work, like the release of Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back (2021)—a three-part doc series co-produced by Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, and the wives of the late John Lennon and George Harrison, Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison, respectively, which prompted a spike in performance for the band’s company Apple Corps. An estate can lend legitimacy to a project, even if their involvement might hinge on certain conditions that would hinder an otherwise unencumbered filmmaker’s perspective.

They also often allow access to crucial archival material, a linchpin that largely determines a branded doc’s value. These contemporary music docs vary in terms of quality and personal agendas, but most of them are produced (or “presented”) by multiple companies befitting the complex web of licensing rights needed to secure the music or footage for a specific story to be told. For example, the three-part docuseries Lolla: The Story of Lollapalooza (2024) was produced in part by MTV Entertainment Studios so that more than 30,000 hours of archival footage owned by the company could be made available to the filmmakers.

Dilley and her team first need to identify a project strong enough to justify widespread rights reconnaissance. Although there isn’t an exact science to this part of development, the Concord Originals team tends to return to relevancy as a north star, whether that be an anniversary on the horizon or a happenstance event that suddenly draws a spotlight to an artist’s catalog.

“We always start with this concept of ‘Why now?’” Dilley contends. “It seems obvious, but because there are so many music-driven stories in the marketplace, you really need to have a purpose behind what you’re building to engage with an audience. Once we have that established, we’ll spend a considerable amount of time coming up with the right approach and format to pitch agents, managers, and talent.”

A docuseries like Stax: Soulsville U.S.A. was a long time in the making, but it began as a proposal from another division. (“Concord is still an independent music company,” Dilley explains proudly. “We are not so big that we have this bureaucratic problem where you can’t have day-to-day conversations between departments.”) Michele Smith, a vice president of estate and legacy brand management at Concord, has been the primary torchbearer and point person for all Stax-related materials since the company’s acquisition of Fantasy Records. She approached Dilley almost immediately after she was hired to pitch her on the project. “[Smith] came to me and said, ‘This story has to be told. You have no idea how culturally important it is and how much deeper we can get than what’s already been done in terms of films around the label.’”

Concord had already started a relationship with White Horse Pictures, a production company that had previously produced a few music docs, including The Apollo (2019) and The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart (2020) for HBO. Together with Polygram, they approached Edelman and his producer, Caroline Waterlow, to join the project. They had both won the 2017 Oscar for Best Documentary Feature for O.J.: Made in America, a multipart film that used the life of a controversial figure to examine the intersection of race and celebrity in America. They were a perfect fit for a series like Stax, which similarly wished to situate the label’s history in a broader social and historical context.

Edelman suggested documentary director Jamila Wignot to helm the project on the strength of her storied work in the nonfiction space. Wignot had worked extensively in television documentaries, directing and producing episodes of PBS series like American Experience and American Masters, while also collaborating with filmmaker Sierra Pettengill on feature-length projects like Town Hall (2013), a portrait of two Tea Party activists, for which they shared directorial credit, and Riotsville, U.S.A. (2022), an archival doc about Army-created fictional towns used to train military officials to combat rioters in the ’60s. Before Stax, Wignot had also directed Ailey (2021), a film that poetically resurrected the memory of Black dancer and activist Alvin Ailey for a younger, more politically astute audience. Her credentials secured her a job that she was suited for anyway: she was listening to Otis Redding on the way to meeting with Edelman about joining the film.

***

Given the complexity of a project like Stax in terms of narrative and rights procurement, it was important for Concord to put together an impressive enough package to take to market so they could presell the series to a distributor. (In this case, HBO ultimately came on board.) During the boom period of streaming services, it wasn’t always necessary to have a full package ready for market. Now, the ever-narrowing state of the entertainment industry demands rigor from companies trying to develop in the nonfiction space.

“A few years ago, there was such an appetite for material during the peak TV stage,” Dilley remembers. “You could go very early with a project to streamers, buyers, financiers and say, ‘Do you want to jump in just on the idea alone?’ Today, I would say that is very rare.”

Dilley and two other members of the Concord Originals team Charlie Hopkins and Wesley Adams, all cite a serious market contraction, especially in the wake of the 2023 strikes and labor disputes, as a reason for a generally reticent approach from buyers in both the nonfiction and fiction space. “The target has shrunk as to what will get greenlit,” Concord Originals’ Vice President of Development Hopkins notes. “We’ve been mindful about what we’re throwing our weight behind.”

However, Dilley and Hopkins believe that the contraction puts productive pressure on teams to develop strong creative projects. “I like to be a little more optimistic and think this is a bit of a reset,” Dilley contends. “There’s so much competition in the marketplace that you need to have every piece buttoned up to be able to compete. The challenging part is there are so many great voices now and not a ton of slots, so figuring out the right combo of people with the right ideas is going to be a major obstacle for all of us going forward.”

Though Concord, with regard to their copyrights, has a wealth of licensing and audience data at their disposal to capture audience trends, there’s still some difficulty in predicting what a buyer might be looking for. (“Mandates shift like the wind,” Dilley jokes.) Any baked-in pre-awareness that draws on audience nostalgia will obviously have a leg up on the competition, but it’s still difficult to forecast what financiers or distributors will throw their weight behind. “Artist profiles still matter,” says Hopkins. “I mean, if you pan out from the music space, obviously true crime stuff still works, but it’s rare that you find one of those that overlaps with a music story. (We do actually keep an eye out for them.) But if you’re going with an artist that is not Taylor Swift, then it pretty quickly does become about a filmmaker’s vision and a proven track record.”

***

In conversations with Dilley and her team, trust frequently comes up as a guiding principle. In the case of Stax, that meant giving Wignot and her team the space to do their job effectively. As much as Michele Smith was working behind the scenes as a producer, the brand manager for Stax Records, and the primary point person for the Stax label, Dilley and her team insist on the importance of providing freedom to their creative partners.

The faith that Concord Originals has in their collaborators trickles down to the types of notes they give the creatives they work with. “We’re not that interested in producing EPKs,” Hopkins insists. “Oftentimes our notes are, ‘The pacing feels off in this section’ or ‘Is this the best archive to articulate this narrative point?’ In the case of documentaries, oftentimes it’s about remembering what the initial vision was and getting across a core idea that we were all excited about from the jump.”

Adams, Concord Originals’ vice president of production and distribution, mentions “factual accuracy” as examples of notes she’s given on nonfiction projects, but Dilley points to a more granular issue that faces documentaries: timing. “Especially in docs, you find that when you move a sequence to a slightly earlier moment, it sometimes provides better context for the story. For unscripted projects, you’re often confined to history, so it becomes about ordering moments for maximum emotional impact.”

When pushed on the specific types of notes they give to doc directors, Dilley insists that their “creative feedback tends to be more historically and factually driven to make sure that we are not leading the narrative in a biased way.” She continues, “In the case of Stax, we were keenly focused on factual accuracy and notes about pacing and flow to ensure Jamila had the reins to tell the story from her perspective and simultaneously create space for the artists themselves to tell their individual stories in their interviews.”

Building trust with estates is an entirely different issue. The team at Concord Originals stresses the importance of organically fostering relationships with rights holders to ensure full participation. Sometimes that means cultivating an association over years to make the case that Concord and other creative stakeholders have their best interests at heart. “Transparency is really important,” insists Adams. “Obviously, not every situation will necessitate that you volunteer all of the information, but simply being accessible to rights holders is crucial. Eliminating the possibility of blurred lines of communication and keeping everyone on the same page confirms that you’re aligned with the same goal.”

“Trust comes from action,” says Dilley. “A lot of times we try to meet with a rights holder directly in person, and if that requires us flying into some random place in the middle of the country, we’ll do it. If you’re talking about an artist and wanting to tell their story, then you need to do the homework and have a vision for why you are the best person to help bring that to life.” According to Dilley, sometimes Concord projects take up to two years to get off the ground because that’s the time needed to foster a fruitful working relationship. “What makes us competitive is we put in that work to gain the trust you need to do the best work.”

Sixty percent of current Concord Originals projects are being developed in-house due to the catalog rights at their disposal, and yet the diffuse nature of music rights still demands a rigorous inquiry to determine where an artist’s full catalog resides. “A lot of times, there are like 18 different rights pieces we need to make a project happen,” says Dilley. “We conduct a huge amount of research at the top end just over where all of somebody’s catalog lives.”

Stax Records may be under the Concord name, but they ultimately own only some of the rights. More than 25 artists were interviewed for the documentary series, and the music or estate rights for each of those artists were scattered everywhere. “Just because we own or represent something, or own or represent a piece of something, doesn’t mean we have all the rights needed to engage,” explains Hopkins. “Maybe we have half the catalog, maybe half is elsewhere. Maybe we have the publishing, not the recordings. Maybe we have the music, not the life rights.”

“In that instance, it really took a village,” Dilley continues. “We had to go to each of those people and say, ‘Here’s why it’s important that you either get interviewed on screen or you allow us to look at your family’s archive or allow us to use these certain songs.’ It really is a relationship business because you couldn’t do these projects without that kind of connectivity.”

A case in point is Billie (2019)—James Erskine’s documentary on Billie Holiday, co-produced by Concord Originals alongside such mainstays as Polygram and BBC Music—which hinges on a series of interviews that journalist Linda Lipnack Kuehl (1940–1978) taped with Holiday’s associates and relatives decades prior in anticipation of writing a biography of the singer. Though she died before she could complete the book, her archive has been a crucial resource for Holiday scholars. Erskine first brokered the deal to purchase the rights to Kuehl’s tapes so that the previously unheard voices that she recorded could comprise the film’s soundtrack and narrate the story of Holiday’s life. He then worked with Concord, which succeeded the Billie Holiday estate, to secure the necessary music rights for the documentary.

Even under the ideal circumstances of Concord generating their own material, putting together a project is, practically speaking, akin to completing a jigsaw puzzle after the pieces have been flung around an enormous mansion. “It’s nice if a partner has a general appreciation for music docs being their own discipline,” notes Hopkins. “Because they are, and there will be added layers you have to navigate through the process. There might be multiple music publishers or multiple record labels; in each, there might be multiple approval parties. A label, a publisher, or a private third party might be the one to sign off on licenses instead of an estate. It becomes about identifying the stakeholders and wrangling the approvals, in each case, that you’ll need.”

***

The thorny instability of that connectivity always hangs over complex rights negotiations—all it takes is for a key intermediator to get cold feet or an estate to come under new ownership for any project to fall apart. In September 2024, New York Times Magazine published Sasha Weiss’s reported piece about Ezra Edelman’s now-scuttled new film: a nine-hour documentary on Prince for Netflix. Initially made with the full participation of the late artist’s estate and featuring a treasure trove of unreleased archival material from Prince’s famed “vault,” the film has been hailed as a masterpiece by the scant few people who have seen it, but it’s unlikely it will ever see the light of day. Since the project’s start in 2019, the Prince estate changed hands, and attorney Londell McMillan successfully sought to block its release over objections about the lengthy runtime and the artist’s warts-and-all depiction in the film.

Edelman’s aborted Prince documentary feels like a prophecy for a film culture filled with authorized documentaries that primarily serve to flatter rather than elucidate, where even the blemishes are heavily controlled and selectively revealed, and archival material becomes a lazy metonym for authority. Concord’s copyright monopoly and editorial hand might give them enough weight to circumvent such a fate. But for every Stax Records, there’s an artist whose concern for good optics will outweigh creative interests.

A company like Concord ultimately has concerns similar to an artist’s estate regarding the image of their copyrights. When they develop a project together with a filmmaker or creative producer, it’s possible, if not predictable, that agendas might clash. Further, involving more parties in a project, with all their associated rights wrangling and archival material, can create an antiseptic product that appears approved by committee. Hopkins contends that Concord strives to ensure that everyone is on the same page early on so that Prince-like calamities don’t occur during or after production.

“Pre-greenlight, we’re probably saying to the estate, ‘If we bless this creative and we bless this filmmaker, the train has sort of left the station.’ Now, an estate can still say, ‘You’ve misrepresented this element’ or ‘You forgot to capture this part of the story,’ but once you’re off to the races, the filmmaker or the financier becomes the primary decision maker from that point forward.”

Hopkins can remember only one instance during his time at Concord that an entity was so prescriptive about how their story should be told that they chose not to pursue the project. “We sort of identified early on that there was not going to be a filmmaker we could find who was going to accommodate their mandate. We didn’t follow through on it precisely for that reason. ”

Dilley insists that authenticity is a paramount concern for Concord and that the collaborators they choose to work with understand that directive. “From our perspective, we’re concerned about factual accuracy, not how we limit what we’re exposing. For a story to be the best version of itself, it has to be authentic, and I think audiences are very attuned to that. That means you have to show the blemishes just as much as the positivity.”

Of course, “authenticity” often just refers to a superficial pretense toward truth. An artist’s participation in a documentary can be all it takes to convince an audience that they’re watching the “real” story, even if it’s a brand-managed version of it. A series like Stax is unique in that it demands cooperation from multiple parties simply to communicate the messy reality of the label’s rise and fall, which has too often been reduced to the simplistic narrative of an alienating strain of revolutionary Black nationalism corrupting an interracial utopia. In reality, craven capitalistic forces, shortsighted decision making, and external tragedies contributed to its slow, preventable collapse. It takes time and the commitment of many people to correct that record and give the true story its proper due.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Spring 2025 issue, with the following subheading: The narrative content division of independent music rights company Concord develops unique fare in a sea of music documentaries.

Vikram Murthi is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and critic. He’s currently a contributing writer to The Nation.