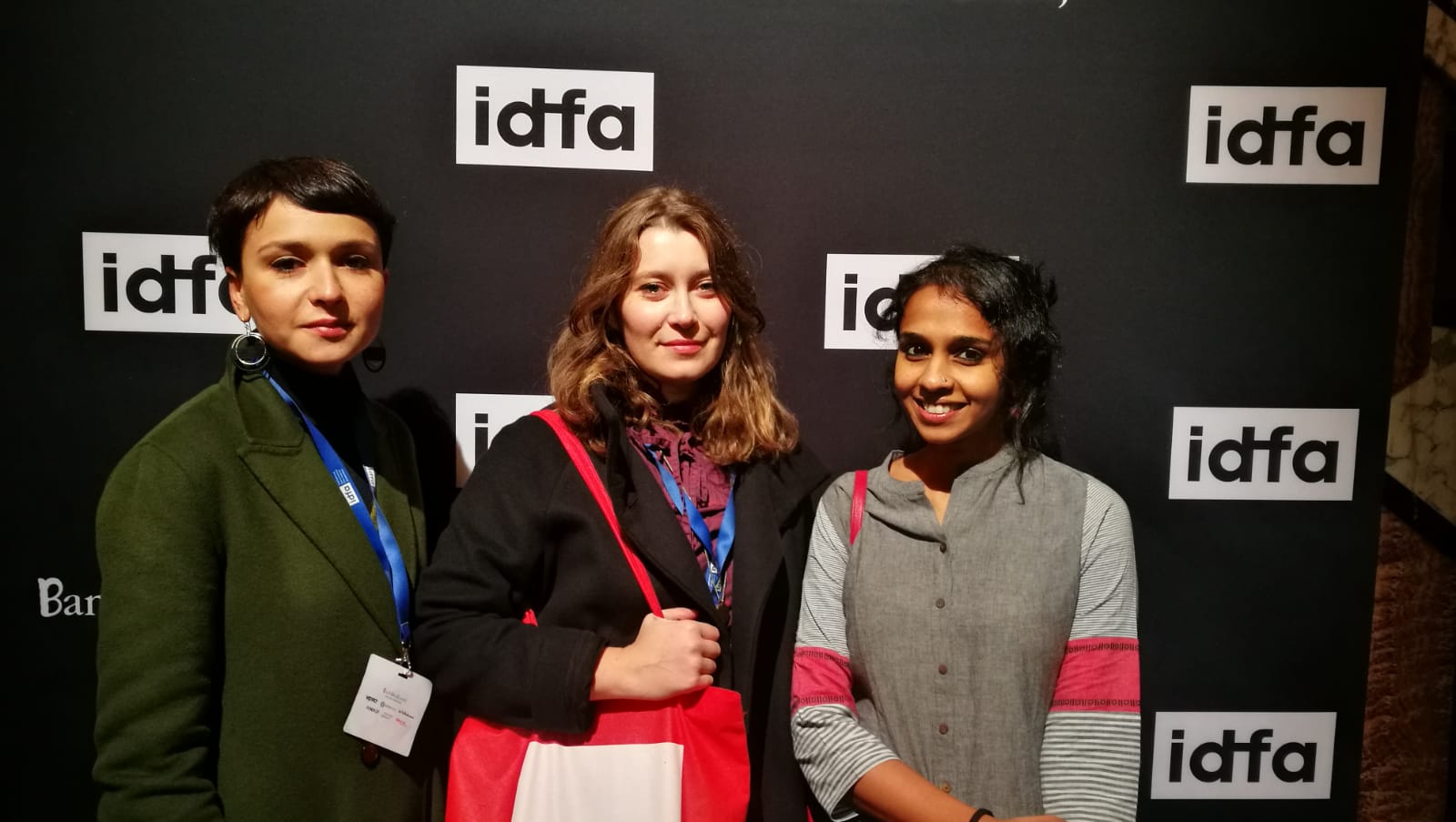

Christina Hanes (L) and Isabelle Rinaldi (R) filming the sequel to A Rifle and a Bag. Courtesy of NoCut Film Collective

Making a Production is Documentary’s strand of in-depth profiles featuring production companies that make critically-acclaimed nonfiction film and media in innovative ways. These pieces probe the creative decisions, financial structures, and talent development that sustain their work—revealing both infrastructural challenges and industry opportunities that exist for documentarians.

“My job is to finish the translations,” Arya Rothe, 34, said near the end of a NoCut Film Collective production meeting, “and”—with a big chuckle, bringing up a grant disbursement of their current film-in-production—“to inform you guys that we have four Euros left.”

“Well, it’s good that it’s not minus four,” interjected Isabella Rinaldi, 38.

“We will go into minus because I have to feed our translator,” Rothe continued, throwing a spanner in the works. “I try to feed him really nice food so that he keeps coming back.”

“Nice!” Cristina Hanes, 33, mumbled sardonically as she moved her cat out of the way and rolled another cigarette.

For the better part of two hours, the three founder-members of NoCut Film Collective waded through backache-inducing questions of business (last-minute applications to film markets), art (“I don’t want to now stress ourselves with this,” Rinaldi said, looking extremely stressed, “but we really need a title for the new film”), other people’s art (swimming eyeballs from hours and hours of roughcuts), and even strategies of emotional support (for suffering directors).

This, it seems, is what a typical production meeting is like in the non-offices of NoCut—boiling over with energy, enthusiasm, and a dedication bordering on desperation. Despite the confabulations through the ether of Google and Zoom, their kinship shines through. Every one of these virtual meetings is stuffed with an overwhelming array of topics, evidence of the extensive support that NoCut provides every production it works with, from pitching festivals and navigating grant applications to handholding filmmakers through the creative process and after (at a meeting some weeks later, for instance, they spend half an hour tearing their hair as they try to find a festival home for a film that’s been in the works for years). To keep track of all these tasks, they need multiple Excel sheets of metadata, lists of deadlines, and confusing content pages for project-related documents. With so many balls in the air, these sessions can sometimes feel dizzying, and everyone sounds wiped out by the end. But there’s work to be done, so they decide to power through and schedule more for Sunday.

How to Start a Nonhierarchical Collective

That NoCut has no physical office, that it is registered in Romania and India (unofficially floating into Belgium), and that its members frequently navigate three different time zones to set up meetings, are all appropriate given its origin story. Rothe, Rinaldi, and Hanes met ten years ago as classmates in DocNomads, the Erasmus Mundus master’s program in documentary filmmaking. Run by a consortium of three universities in Portugal, Hungary, and Belgium, DocNomads is a fully funded course for students from all over the globe, with an emphasis on teamwork and coproduction, which explains why many of its graduates often end up working with each other later. Hanes and Rothe became housemates in their first semester in Lisbon; in the next, in Budapest, Rinaldi moved in. Helping each other with student projects, the three women developed a working rapport even as they fell into a thick friendship.

Once their graduate program ended in 2016, the trio returned to their respective hometowns, but they wanted to carry on working together. “We didn’t want to lose this common understanding we’d garnered together in those two years,” Rothe told me, on another video call. “And at that moment,” Rinaldi jumped in, “the most obvious thing was for Cristina and me to go to India.”

With vague ambitions of finding something to film together and very little planning, Hanes (who lives in Transylvania) and Rinaldi (who moves between Brussels and Rome) decamped to Rothe’s house in Pune, in the western Indian state of Maharashtra. For three months, they spitballed ideas, scouted locations, and came up with a name for whatever it was they were trying to do: NoCut Film Collective.

The name expressed their desire for a nonhierarchical production setup engaged in a patient cinema capable of expressing reality directly. “We always knew it would be a collective and not a company,” Rothe said. “The ‘no-cut’ was close to our idea of cinema.”

In India, the three filmmakers started visiting settlements of surrendered Naxalites, Maoist rebels who had been engaged in armed resistance against the Indian state’s sustained policy of dispossessing Adivasis and poor locals in the name of development. One erstwhile rebel in particular captivated them: The day before they were to leave the jungles of central India, they met Somi, who fell in love with her husband Sukhram in a Naxalite commando unit. The couple had traded in their guns a few years earlier, under the State’s “capitulation-cum-rehabilitation” policy, to try and start afresh. After months of scrounging for funds, NoCut returned to film the couple’s newfound currents of domesticity and their entanglement within the fluctuating tripwires of a neglectful state. The end product, Rothe said, “consumed us for three years.”

A Rifle and a Bag (2020) documents Somi and Sukhram as they aspire to the regular flows of the quotidian in the face of the continuing scrutiny of an incompetent bureaucracy and the vagaries of an insensitive society. With a name like NoCut, it is not surprising that the collective’s first film uses a static camera that meanders through long takes of the couple raising their kids, navigating the constant distrust of other villagers, and trying to procure a caste certificate so their son can stay in school. An impressionistic and empathetic portrayal, the film is shot through with Somi’s articulate voice even as it confidently effaces the voices of its authors.

At first, this may seem ironic, because NoCut is drawn to distinctive authorial voices and creative visions that have compelling stories to tell. Indeed, it is one of the ways in which they decide, if invited, to jump aboard someone else’s film as coproducers. But Rifle’s willingness to foreground the voices of its subjects instead of its authors is also in some ways a feature of many films that come out of the DocNomads program, which encourages a reflective and personal approach to documentary filmmaking that is grounded in a participatory and observational sensibility.

Despite not having parlayed their frequent festival presence into more directly commercial gigs (something I’m not sure they want to do in the first place), NoCut has been quietly making a name for itself in the documentary and independent film communities. They receive fellowships and grant funding consistently, and their films play at most top-tier documentary festivals. But their true triumph may well be an embodiment of the DocNomads ethos—a genuinely collaborative and transcultural practice that is rooted in its genius loci even as it transcends continental borders.

“They really helped us refine our funding proposals and the edits of our film,” Rajan Kathet, an old DocNomads classmate of the trio, told me. “Their emotional support—which we need the most during our years of filmmaking—was invaluable.” Kathet got in touch when NoCut was making Rifle, hoping they would collaborate on a film he was codirecting. Familiar with his student work, NoCut signed on. “We didn’t know in the beginning what shape our collaboration would take,” Hanes said. “In the end, it took this shape of a coproduction.”

The resulting film, No Winter Holidays (2023), shares a certain affinity with Rifle, a sense of gazing silently into the stiller corners of people’s lives, where the bits of crumpled paper and the detritus of dreams lie. No Winter Holidays is about the two old caretakers of a deserted Nepali village in the unforgiving Himalayan winter who also happen to have each been the “other wife” to the same dead husband. As in Rifle, the camera peeks into intimate spaces—bedrooms, kitchens, clotheslines, backyards. And like Rifle, No Winter Holidays is composed primarily of long takes; we keep seeing the two old women sitting by a fire or on a balcony in the company of unrelenting snow. Not much moves. NoCut, it would appear, is deeply invested in authorial voices that know how to mute themselves. As Miles Davis once said, “It’s not the notes you play; it’s the notes you don’t play.”

How to Operate as a Transcontinental Indie Doc Outfit

NoCut has a starkly equitable structure, almost a nonstructure when seen in relief against standard industrial filmmaking in India, and especially Bollywood, with its clearly demarcated production roles and crew structures. The collective, Rinaldi explained, “can take any configuration according to what the project needs, based on personal skills, logistics, availability, and even just intention, like, the willingness to do something.” Once someone’s role has been defined, though, it usually stays that way for the rest of that project.

For an example of these shifting roles, consider their first film, A Rifle and a Bag, for which all three members shared writing, directing, editing, and production credits. However, because Rothe lives in India and could communicate with the characters in Hindi and Marathi, she did more of the daily production work, while Hanes and Rinaldi handled sales and the administrative officialdoms of the festival circuit once the film had been made. Now, in the middle of shooting the sequel to Rifle (whose working title, Green the Fire’s Tint, they aren’t entirely happy with), they’ve decided to stick to the configuration of the previous film. Hanes will remain, for all practical purposes, the cinematographer, while Rinaldi, who oversaw Rifle’s sound, has decided to continue handling that aspect of the new production.

This unorthodox setup appears to be as beholden to empathy and trust as it is to efficiency and order. With the sequel, said Rothe, “our characters are also used to seeing us in certain roles because it’s further along in the same story and they’re the same characters. So, we didn’t want to really shift from that, because we wanted to pick up the intimacy from where we left off.” By prioritizing their off-screen relationships with their characters so that Somi, Sukhram, and the children are never uncomfortable, the filmmakers have decided to balance operational productivity with the emotional needs of their subjects.

The NoCut coproduction universe is one of switching constellations. Since Rifle, the collective has been working on producing or coproducing four films by other authors. Rinaldi and Hanes were more involved in No Winter Holidays and received official co-production credits (three other production houses were also involved in that film), while Rothe officially co-produced, with the Belgian company Clin d’Oeil Films, Kinshuk Surjan’s Marching in the Dark (2024), a documentary about grief and resilience amidst the phenomenon of escalating farmer suicides in rural India.

Initially, the three members watched the research material for No Winter Holidays and Marching in the Dark together, like they do for all their projects. Next, they concluded that while No Winter Holidays required the kind of creative inputs that Rinaldi and Hanes were better suited to provide at the time, Marching needed an Indian producer on location to help the filmmakers. Thanks to NoCut’s fluid structure, though, Rinaldi ended up watching more recent cuts of Marching despite Rothe having been much more involved in the project as it was being shot.

For a significant chunk of one of the meetings I attended, the three producers were busting a gut trying to figure out what was best for Surjan and his film, and where to premiere Marching in the Dark (which eventually premiered—and won a Special Mention in the new Human:Rights Award category—at CPH:DOX in Copenhagen, one of the largest documentary festivals in the world). NoCut helped make visa appointments for the film’s protagonist, Sanjivani (the widow of a farmer who committed suicide in the face of mounting debt and crop failure), who was present for the premiere in Denmark.

Surjan, another DocNomads alum, also values NoCut’s noncommercial thrust, which is geared entirely toward the filmmaker’s needs. “Arya, Cristina, and Isa follow an egoless process, a perfect synergy of three distinct minds, each with their strengths,” he told me in an email. “Their shared passion for cinema drives them to craft unique, unconventional stories that may not be easy to tell or sell.”

The collective, in its endeavor to help other filmmakers realize their artistic visions, gravitates toward collaborations with emerging directors, ideally engaging with a project as close to its nascent stages as possible. “Especially with first-time filmmakers, we feel that’s when we can really contribute,” Rinaldi said. “It’s that first stage, where some filmmakers don’t know what to do. We can refine the way they present their project to the industry. Writing the synopsis, writing the treatment, editing the trailer, making a strategy for funds. That’s when we can be impactful, because we’ve been through it. We know the drill. And we also know the emotional struggle.”

“I think we all agree that the most important aspect is the gaze of the director,” Hanes elaborated, describing how NoCut tends to get invested in such projects. “This gaze should be genuine … inquisitive … and driven by a real curiosity in the theme or situation or characters that they are exploring.” Because a lot of their work is remote, this is not always an easy appraisal to pull off. It is where the initial research material has to do the heavy lifting.

“One of the biggest things is to actually see if we like the material, because that really, really speaks a lot about things the director might not want to say out loud,” Rothe said. “And we often take a long time to watch a lot of material.” While this material varies depending on the project, it usually includes many hours of reviewing dailies, poring over audiovisual proxies of roughly edited scene assemblies, and going through a considerable number of rough cuts.

“We don’t subscribe to this idea that producers should only stick to making the budgets, making the financial mapping, because even to do that, we also need to know the film deeply.”

NoCut is drawn to those causes that many established production houses, with their algorithmically guided and focus-group-driven offerings, tend to abjure. “We don’t look for projects that are commissioned by bigger companies. These author-driven creative documentaries are not the kind of thing that OTTs like Netflix or Amazon would jump at.” Consequently, NoCut films end up on smaller streaming platforms that are aimed at niche audiences, like MUBI, GuideDoc, True Story, or the Doc Alliance’s DAFilms.

If NoCut produces your film, you get bespoke, not boilerplate. Even if that means they’re up all night working on the application for the grant that’s just right for you. “Our skill set is more aligned with applying for the grants and finding the money that’s actually accessible to the kinds of stories we like to work on,” said Rothe. “It’s not just because we are directors that we have this skill set. It’s because we have received a lot of the funds that are significant in, let’s say, the small creative documentary world. So that also helps us help other filmmakers.”

NoCut swims in diverse waters. Andreea Dumitriu met Rinaldi and Hanes while presenting a film plan at the fARAD Festival de Film Documentar in Arad, Romania, when they were all attending the fARAD Lab’s development and sound workshop. Dumitriu had filmed a kilometres-long queue of a few hundred thousand pilgrims in the Romanian town of Iasi and was thinking of producing a short film. NoCut offered to help find funds for postproduction, so Dumitriu decided to ask them to produce. “They understood and supported my artistic vision, and I had the trust that they could be a good sparring partner in the editing phase,” she informed me recently. “They had experience with applying to international funding and were ready to invest their time in doing that with my film.”

Logistically—and linguistically—it’s not easy being a transcontinental indie operation. In the films they’ve made or coproduced, you can hear Gondi, Hindi, Madia, Marathi, Nepali, Portuguese, and Romanian. When they first set it up in 2016, the collective was incorporated as an Indian entity under Rothe’s name. The next year, Hanes registered NoCut Romania. The two have contracts with each other that are largely defined by the Council of Europe Convention on Cinematographic Co-Production. Rinaldi is fiscally registered in Italy as an EU freelance contractor paid by either NoCut Romania or NoCut India. Funds tend to be raised both individually and collectively at various stages of a project, and the contracts outline this process.

In some ways, NoCut exemplifies the increasingly globalized practice of co-productions between multiple countries, thanks especially to the European Union’s promotion of integrated markets for cultural exchange across borders. Operating in multiple countries is a way for the collective to broaden the reach of its films, collaborate with different artists, and explore greater funding avenues.

All their accounts are on one easily accessible spreadsheet, so everyone knows what’s going on in all three entities. “Even though we have blind trust between us when it comes to money,” Rinaldi told me unhesitatingly. Unlike a classic production house, NoCut raises money and makes its films in increments, getting enough funds to shoot a chunk and then repeating the process.

How to Pay the Bills During Creative Collaboration

I keep returning to the idea of an anarchist collective whenever I consider NoCut’s organizational plasticity. “But we are not fans of chaos,” Rothe insisted, describing their functioning as “disciplined fluidity.” There is no suffocating sense of an inescapable adhesion to the organization for any of its members. Every member also pursues individual projects outside of the collective. Rothe has completed several work-for-hire projects for streamers and broadcasters such as Netflix India and Prime Video; Rinaldi directed one episode of a Belgian anthology TV series, an international co-production led by Off World, and held production and editing roles on other creative documentaries; and with Radu Stancu, Hanes oversees the production of all documentary projects at Romania’s deFilm. A complex, interconnected mixture sustains the daily bread.

On their own films, they make it a point to pay every crew member fairly. “The Indian film industry in particular is based on extreme hierarchy,” Rothe sighed. “Different crew members are paid, and treated, drastically differently, which we don’t agree with at all.” Whatever—if anything—is left over, they split equally.

“NoCut is perhaps one of the few production houses born from DocNomads that has carried on its spirit of egoless collaboration beyond any borders,” Surjan later wrote me. “In this long and lonely journey of making films, having friends like Arya, Cristina, and Isa, who not only provide constant advice and support as friends but also serve as coproducers, is truly invaluable. [In their case, it’s] even more remarkable since we have very different processes of making films.”

Splitting the pay, splitting the heartache. Despite being a small indie collective, NoCut seems to commit to industrial-scale emotional grunt work. I wonder if it’s because they are all women, running a production house unimpeded by testosterone. The unpredictability of documentary filmmaking and its affective riptides—“You end up feeling a lot more vulnerable on a documentary shoot,” Rothe said, “because you are dealing with real emotions, real people, real situations”—has for all three members become easier to navigate through collaboration. The collective has tethered them to an emotional anchor and sparked a sense of solidarity.

“What’s happening in the world, which is quite disturbing to be honest, also affects our storytelling,” Rinaldi grimaced. “And the collective helps us share, in some ways, the pain that we all feel in our world. And it gives—I mean, coming from the worst possible space—but it also gives us the motivation to keep doing what it is that we do. And in a way, it increases the stubbornness in doing this job.”

“The idea of resistance has become much more collective for me,” Rothe told me on our final call. “Even with our small film, we are still tackling all these big feelings. I’m not saying we are making a film that is great for the world, but it’s the other way around—making films helps us cope with what’s going on outside, together. This feeling would be, for me, very limited if I did not have Isa and Cristina by my side.”

Sudipto Sanyal is a writer in Bangalore who wants to revive his old pirate radio show, but the cats keep getting in the way.