“Examining Their Eyes, Hands, Hair, Mouths, and Posture”: Darius Clark Monroe on the Intimacies of Docuseries ‘Dallas, 2019’

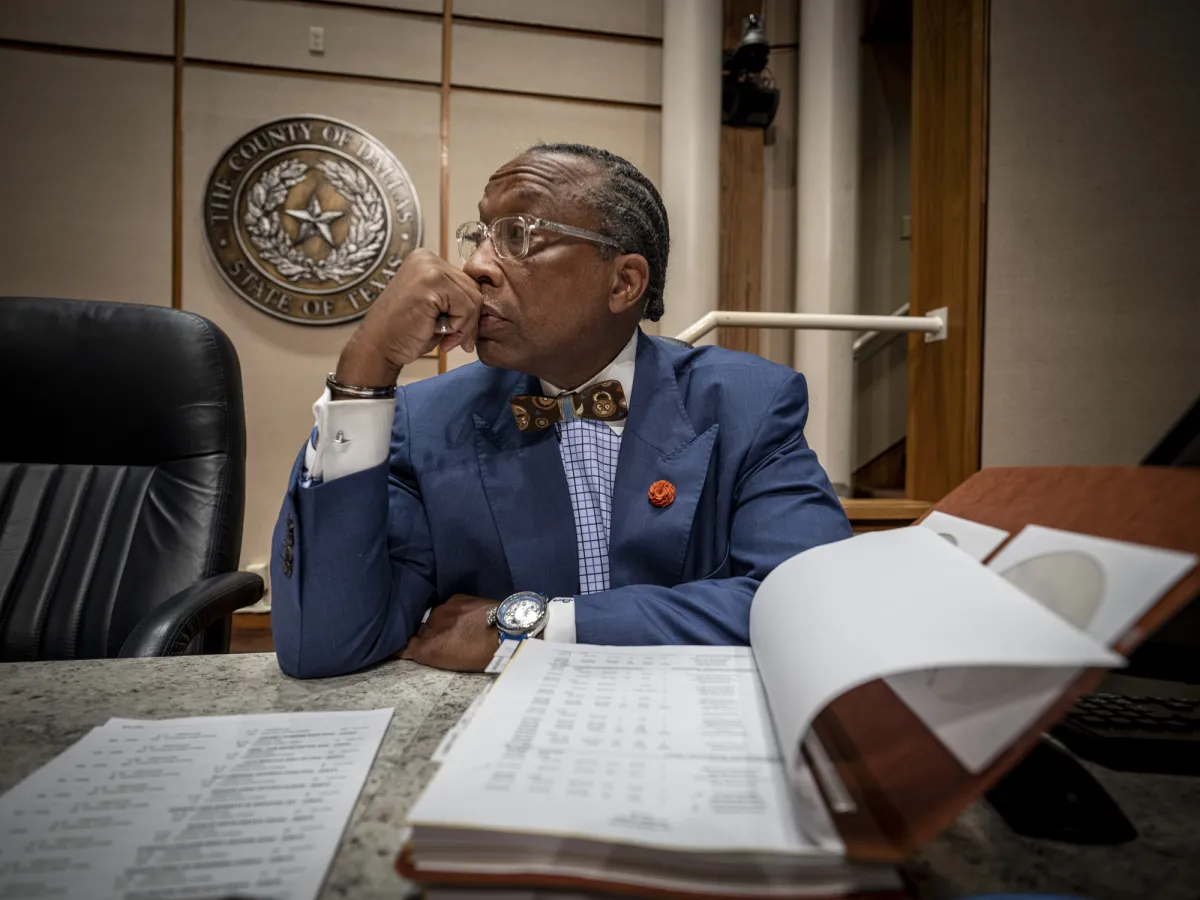

Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price. Courtesy of ITVS

Darius Clark Monroe has been on my radar for a decade, ever since his feature debut Evolution of a Criminal, a revisitation of the robbery the filmmaker committed when he was a teenager and its impact on both loved ones and victims, which world premiered at SXSW back in 2014. (Later that year it took top honors at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival, where I programmed the film.) Since then Monroe has been on an artistic evolution as well, continuing with such unconventional projects as the 2018 Tribeca-debuting short Black 14, once again EP’d by Evolution executive producer Spike Lee, which explored the story of 14 African American student athletes dismissed from the University of Wyoming football team back in 1969 for speaking out against racism in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; and the doc quadtych Racquet, which played the Whitney Biennial the following year. Monroe’s eclectic CV also includes writing and directing for Terence Nance’s Peabody Award–winning HBO series Random Acts of Flyness (2018).

Now Monroe has returned home, with the five-part docuseries Dallas, 2019 bringing the Houston native back to the Lone Star State for a “five week observation of the city of Dallas and its people.” Each episode tackles subjects ranging from environmental racism, injustice in the criminal justice system, to education and beyond, all through a chorus of characters that breathe life into those cold abstract concepts. To learn all about the series, which premiered over two nights on Independent Lens on January 3 and 4, Documentary reached out to the Brooklyn-based filmmaker. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: So how did this project come about—and why focus on Texas and specifically Dallas, since you’re a Houston native?

DARIUS CLARK MONROE: ITVS was developing a docuseries back in 2017, before I arrived on this project, an adaptation of Jamie Meltzer’s Dallas-set True Conviction (2018). In December 2018, Noland Walker, our executive producer and a co-programmer at ITVS, reached out to me about collaborating on an original docuseries. My interest was immediately piqued when he mentioned the team involved, and of course my home state of Texas. I had known Noland for several years and had also become good friends with Lois Vossen, who I met at SXSW when we world-premiered Evolution of a Criminal in 2014. I was also intrigued by working with and learning from Seth Gordon, an incredibly smart and seasoned Hollywood director and producer. But what sealed the deal is that the team was fully open to my creative take on what this series could potentially be. I wanted to widen the scope and reorient our understanding of crime and justice, focusing on public institutions through the exterior and interior lives of the people who run and are impacted by them.

For a brief moment we did think about taking this to my hometown of Houston, but I was more interested in going to a place that felt both foreign and familiar. I’d been traveling to Dallas since I was a kid—Six Flags Over Texas always had more and sometimes better rides than AstroWorld—and there’s been a competitive rivalry between the cities my entire life. Houston is the fourth largest city in the country, a melting pot metropolis, and yet as a narrative Dallas tends to truly represent the state. I tried hard not to like Dallas, but after moving there for this series I was really blown away by how similar the two felt, and really floored by the amount of love and care we received while there. I’m forever grateful to the people of that city.

D: How did you choose your protagonists? Were other storylines left on the cutting room floor?

DCM: Along with Seth Gordon, our series co-creator and EP, Crystal Issac and Akil Gibbons, our amazing series story producers, and our EP Alon Simcha, we developed this project in Brooklyn for six or so months before we moved to Dallas. While brainstorming we created a graph/diagram that was a participant wishlist, casting the participants before meeting them. Some people we immediately knew that we wanted to observe and shadow based on their roles in the city and the institutions they served, like Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price and former Dallas Superintendent Dr. Michael Hinojosa. Others we confirmed once we moved to Dallas.

Our story producers were already tracking the story of Marsha Jackson and Shingle Mountain, so she was on the list as well. Initially, we wanted to follow Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson, but every single person we met said we should try to follow City Manager T.C. Broadnax instead. Zimora Evans we discovered while filming at Abounding Prosperity with Dallas County Director of Health and Human Services Dr. Philip Huang (who initially said no thanks, but then agreed after observing us film with Dr. Hinojosa at a leadership conference). This series is truly a collaboration between the artists and the participants. We observed and shadowed everyone for months before we started to film.

Regarding other storylines and characters, there were definitely a few that didn’t make it into the series, though the majority of what we did film is onscreen. Fortunately, we were very efficient during production.

D: The series has this surprisingly ethereal quality, with a sound to image juxtaposition I found a bit reminiscent of RaMell Ross’s work. So how did you go about wedding the sound design to the footage? What was that editing process like?

DCM: I appreciate RaMell Ross’s work. There are many really interesting artists who have been using sound to image juxtaposition to further deconstruct the ways documentary films are crafted and experienced. I think of the work of Crystal Kayiza, Ja’Tovia Gary, Garrett Bradley, Arthur Jafa, and Sky Hopinka. There’s always been a push to work outside the form and norm, especially for artists who are rooted in the diaspora and Indigenous. I don’t believe this is new. I’ve been manipulating sound and image for well over a decade. I think about the sound design work of Paul Davies on my short narrative film Dirt (2015), which has no spoken dialogue or music. Or the sound design and sound editing work on my previous short doc series Racquet. Leading with sound is always my initial inclination. Conveying mood, tone, an idea, without music or spoken words or linear imagery.

The ethereal quality is also intentional. I owe the look and feel of this series to the great and dynamic work of DP Christine Ng. For one of our initial discussions we met at the Dallas Aquarium at the suggestion of my brother, who also worked on the project and found the aquarium inspiring, which it was. So going back to my earlier comment about a city feeling both foreign and familiar, that concept was grounded in the ethereal nature of the visuals and sound design of using glass and audio to bring further clarity or to distort reality. We also knew we wanted to be intimate and close, deeply observational; not simply studying participants in a room or space, but literally examining their eyes, hands, hair, mouths, and posture.

Lastly, the editing process is always a joy because I’ve been fortunate to collaborate with Doug Lenox, my dear friend, NYU classmate, and editor for over a decade (who’s also a filmmaker and artist in his own right). Like with Christine, Doug and I have known one another for almost 20 years so we have a shorthand. We both have an affinity for sound design and unorthodox sound to image juxtaposition. Though structuring this series took years, the ethereal style and tone was present early on.

I also want to shout out Eli Cohn at Nocturnal Sound who constantly exceeds my expectations. I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with Eli on my last two projects and we always challenge one another. His instincts are also outside the box and speak to my style and process.

D: Given your own personal experience with the criminal justice system, I’m also curious to hear what the interactions with characters like the sheriff or the judge or the bail bondsman were like, some of whom seemed guarded or at least self-conscious. Was that experience difficult or perhaps enlightening?

DCM: The interactions I had with Sheriff Brown, Judge Givens, and bail bondsman Buckley Chappell were genuine and very positive. These are individuals who are naturally guarded in real life based on their line of work. They knew that I was the director of the series, and they also knew that I was formerly incarcerated.

It took a lot of effort and trust to get them to participate. I honestly feel that they are who they represent themselves to be in the series. They definitely didn’t change their personalities because of me or the camera. We were given the opportunity to shadow these individuals for an extended period before filming; that time allowed space for us to grow comfortable around one another, get to know one another, break bread and again, earn trust.

What I found fascinating is that despite this layer of professionalism, once we started the interview process, doing away with cameras and crew, a window into their personal and private self was further revealed. Their interviews are the backbone of the series, and I found all of the participants to be deeply transparent and not self-conscious at all.

In addition to giving their time to be observed and interviewed, they also provided crucial access. Sheriff Brown allowed us to follow her at work, but she also gave us access to the entire jail, intake, holding, and solitary. She gave us access to her spiritual world at church. She gave permission to see what’s not normally seen, particularly by outsiders. The same goes for Judge Givens and Buckley Chappell. They didn’t just give us themselves, but allowed us to observe their places of work, these institutions, separate from them. That takes trust and that’s not common, especially in a town like Dallas.

Overall the experience was very enlightening, but there were some difficult moments. When it came time to film the jail tour with Sheriff Brown, I was dreading it. Not because the shoot itself would be an issue, but the thought of being confined inside a locked jail gave me a minor panic attack. The shoot was scheduled for 11 p.m. and I felt sick to my stomach the entire day. I couldn’t shake it. Even just before we went into the jail I paced around out front, taking deep breaths. Once we were inside and filming, I completely forgot about my nerves and went to work. All of my thoughts of claustrophobia and anxiety vanished and the time seemed to fly by. After that evening we filmed inside the jail several more times, but I can still recall how tough it was to convince myself to go inside.

The most challenging day of all, though, was shadowing the Dallas County Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Barnard. There’s no other way to describe the experience other than fully existential. I felt outside of my body. I’d never been inside a morgue before. Dr. Barnard was kind enough to leave me there to observe several ongoing autopsies that were taking place that morning. I don’t believe I’ve ever cried so hard.

I left the facility and everything alive felt weird to me. The line between life and death is so thin, unbelievably so. That visit put a lot into proper perspective. When Christine and I went to shadow Dr. Barnard a second time she had the exact same response that I’d had. We cried together. Both of us were stronger and better by the time production came around. The reality of our mortality can be jarring and also healing. There’s no hyperbole when I say that this shoot, this project, changed my life.

D: Have all the characters seen the series? What’s been the feedback?

DCM: Most of the participants have seen the series. From those I’ve heard from, the feedback has been very positive and really encouraging. They’re proud of this work. Though I was nervous about Dr. Huang seeing it because I knew we had some tough days while filming with him. On several occasions he’d find himself in a heated discussion and never once told us to turn the cameras off. He watched the series and his message to me was beautiful—he was honored to be a part of this. That’s been pretty consistent. This series was created with love, immense care, discernment, openness and respect. It was created with gratitude and humility. It was created from a deeply human and spiritual place. And I strongly feel the final work is a reflection of that.

Lauren Wissot is a film critic and journalist, filmmaker and programmer, and a contributing editor at both Filmmaker magazine and Documentary magazine. She also writes regularly for Modern Times Review (The European Documentary Magazine) and has served as the director of programming at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival and the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival.