“The Closer You Get to the Truth, the More You Have to Include Contradictions”: Johan Grimonprez on ‘Soundtrack to a Coup d’État’

Johan Grimonprez. Image credit: Arlene Mejorado

No summary could ever do justice to what Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez has created through his audiovisual-textual collage Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (2024). Although the internet is already populated with numerous texts comparing this creative documentary to a jazz suite, often using aural adjectives such as thrumming, buzzing, and beating, written language seems to fall short in capturing what Grimonprez describes as “cinematic space” and all that it is capable of.

The year 1960, famously called the “Year of Africa,” serves as the political, social, and cultural matrix on which Grimonprez builds his manifold narrative—moving back and forth in time and space, layering sound, image, and text with texture and depth. He delves into the early days of the Democratic Republic of the Congo—one of 17 African countries that had freshly gained independence—and examines the joint political and military machinations of the United States and Belgium that would ultimately lead to the assassination of its charismatic young leader, Patrice Lumumba.

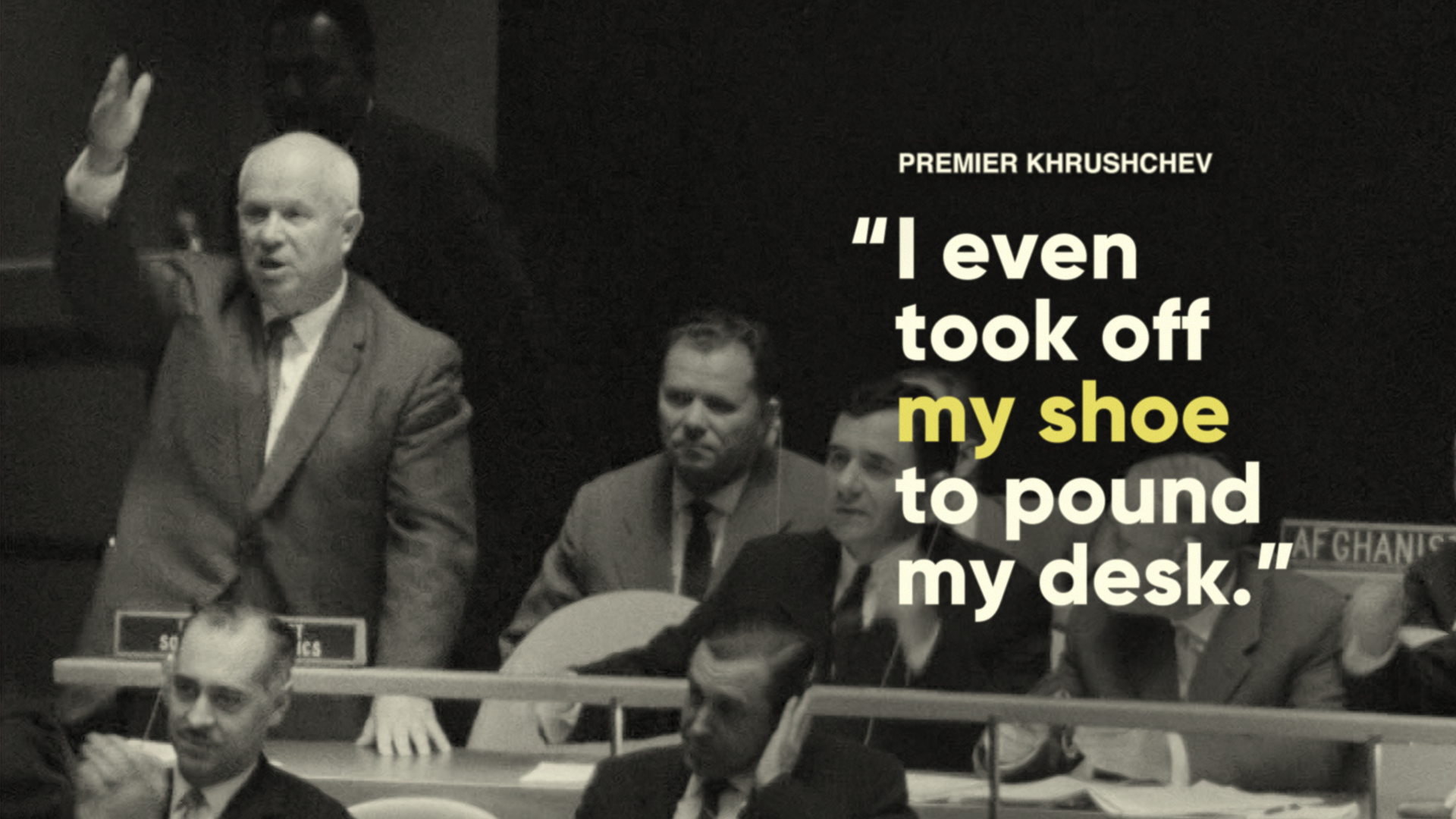

Along the way are many detours, starting with the 15th General Assembly of the United Nations, where leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement—along with the notorious Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev—clash with the Western world. Another thread emerges through the involvement of Black musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, and Nina Simone, who were appointed “Jazz ambassadors” of the U.S. and sent overseas during that period—unaware that the title would prove to be a vile euphemism, a smokescreen for their conspiratorial activities worthy of a spy film.

If going off on a tangent is the film’s modus operandi, talking to Johan Grimonprez is no different. Now an Oscar nominee, the documentarian comes well-prepared, armed with the quintessential skills of an avid researcher and a seasoned orator, opening new tabs in our minds with each question while anticipating potential criticisms with humility and curiosity. Documentary magazine sat down with Grimonprez to discuss Soundtrack to a Coup d’État in his format of choice: a dialogue. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: Soundtrack to a Coup d’État is a film of clashing forces—sounds, images, and texts are continuously confronted, combined, and transformed, without giving predominance to any one medium. But if we take Shadow World (2016), where Andrew Feinstein’s eponymous book forms the main conceptual framework, your relation regarding the same narrative devices seems very different. In what way do the subject matters inform your formal choices in your work?

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Shadow World came out of a collaboration with a journalist, so the modus operandi for telling the story had different conditions and required investigative vetting. Many of the stories had to be vetted by three independent sources. That’s why, perhaps, its poetry comes from a distinctive place. Shadow World was very much about dissecting how war has become privatized and how the whole lobbying industry—which is based on a revolving door between the army, the defense industry, which I prefer to call the war industry, and the political theater—functions. Much of what Chris Hedges would call corporatocracy or corporate coup d’état is reflected in how those lobbyists who worked in the war industry are later paid by the very same system. Take for example, Dick Cheney, who got into politics, then went back to being Halliburton’s CEO, and vice versa. That revolving door metaphor very much defines what happens with foreign policy. In addition, the translation from a book to a film is a different process, and I thought it was crucial to examine the war industry’s relationship with the Global South—something that wasn’t featured in the book. So we [added] figures like Marta Benavides, Vijay Prashad, and Eduardo Galeano.

D: I was looking at your website and came across the conversation you had with Catherine Bernard in 2009, where you mention Khrushchev’s shoe incident. Your fascination with this event dates back at least fifteen years. How did it evolve into the focal point of Soundtrack to a Coup d’État?

JG: Being born in the sixties, I was a child of the television generation. The divide between East and West, which has somehow resurfaced today with Ukraine and China, was already a significant part of how I grew up and understood the world. As for Khrushchev slamming his shoe—I knew about the incident, but I was never aware that it was related to the Belgian Congo. That’s something I only learned through my recent research. Soundtrack to a Coup d’État is structured like a general assembly—it’s the leitmotif of the film, upon which all the other stories are anchored, and the pinnacle of that is Khrushchev slamming his shoe.

With Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, as a Belgian, I naturally had my own perspective growing up—even on a story I didn’t know. It was something I had to explore myself during the making of the film, and as I delved into history, my findings were completely opposite to what I had been taught. But I also wanted to build a dialogue—an alliance. Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997) was inspired by a dialogue between a terrorist and a novelist, featured in Don DeLillo’s Mao II. While Double Take (2009) revolved around an alliance between Tom McCarthy and Jorge Luis Borges, it was also translated into both Borges and Hitchcock confronting themselves.

D: One senses a conscious decision on your part, as a Belgian filmmaker, to introduce voices that would be entitled to tell these stories, while also avoiding giving predominance to any one of them. How did these characters emerge?

JG: The characters in Soundtrack to a Coup d’État all come from an extended family and share a sense of displaced homelessness. Achille Mbembe talks about the sense that homelessness has become global and that we are all colonized in our minds. It is what Michael Hart would call global apartheid—yet global apartheid is not the same as the wall in Gaza or on the U.S. border with Mexico; it is actually domesticated inside of us. So, it was crucial for me to include voices like that of the Belgo-Congolese novelist In Koli Jean Bofane. His stepfather was a Belgian colonialist rubber baron who kidnapped his mother and forced her to marry him. Bofane, as a six-year-old, lived through independence and had a stepfather and half-siblings. His stepfather, Georges Casse, had a camera. Much of the footage of In Koli Jean Bofane, as well as many home movies in the film, were shot by this Belgian rubber baron.

As for Andrée Blouin, I had found scattered mentions of her here and there, often called the “Mata Hari of Africa.” She was also labeled a communist and a prostitute. They wanted to assassinate her, to erase her from history, because she had a very articulate voice. She was a threat to the Belgian authorities. But one must always know how to read between the lines. I knew that this woman must have been far more interesting than how she had been described.

Her memoir, My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, was out of print and very hard to find. I got in touch with her daughter, Eve Blouin, and managed to get a copy of the memoir. But she also sent me a reel of undeveloped film, which turned out to feature Andrée as a two-year-old during that period. Bofane was six, and she was two—her mother had been forced to leave the child behind when chased from the Congo during Mobutu’s reign.

Andrée Blouin herself had a French father and a Central African mother. She says in her book that she never felt a sense of belonging—that she was neither Black nor white. As a mixed-race child, she was not allowed to live with her mother and was placed in a Catholic orphanage, from which she ran away at the age of 16. In her case, too, we see a mixed family that creates a sense of displacement. It was also her French father who used the camera—the colonial side that represents the authoritative gaze.

The voiceover narrator who reads Andrée Blouin’s words is Zap Mama, who had a Belgian father and a Congolese mother. Her father was killed in East Congo during the uprisings, and she had to flee to Brussels with her mother. When she was reciting that passage by Blouin, she said: “I don’t agree with that. I feel 100% Black and 100% white.” She had a completely different understanding of that sense of homelessness.

Conor Cruise O’Brien’s words are read by Patrick Cruise O’Brien. His voice sounds Irish, but he’s actually Ghanaian. Conor Cruise O’Brien adopted Patrick when he was appointed vice-chancellor of the University of Ghana, and because Patrick was raised in Ireland, his Irish accent closely resembles his father’s. When you think of all these characters, I think we all feel displaced from a political scene.

D: Since you refer to truth as dialogical, we can also see that it largely depends on the material, technological, and archival resources at one’s disposal. If you had made this film 10 years ago, you wouldn’t have had the same knowledge-making and research tools. To a great extent, truth is always historically limited.

JG: I agree that truth is historical, but I don’t engage with the whole notion of post-truth—believing in it would be a contradiction in itself. I often quote Voltaire, who said, “History is the lie commonly agreed upon.” It’s true. If Ludo De Witte hadn’t published The Assassination of Lumumba in 1999, they wouldn’t have launched the parliamentary commission to investigate the government’s complicity. And even then, it was already quite late—the findings didn’t come in until 2003 and 2004.

But there is something to labeling and how truth depends on the perspective from which you look. If you were born in Gaza or in a refugee camp and then pushed across the border to Egypt, your sense of truth would be different from that of someone working as a lobbyist for AIPAC in Washington. Words are heavily laden with meaning. Why do we say “collateral damage” instead of “people are being killed?” Language is already ideologically coded.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja is a Congolese scholar who became the UN representative to the Congo and wrote a book on the country’s history from its own perspective. He said that if Congolese people want to write their history, they have to go to Brussels because many of their sources are still archived there. Especially during Mobutu’s reign, there was a different understanding of nationality; politics functioned as a kleptocracy, and history was taught in schools in a highly distorted way. When Nzongola-Ntalaja wanted to access this history and rewrite it, he had to go through these same sources.

D: That is also the main dilemma of the decolonial impulse. To embrace it, one must first navigate colonial discourses, archives, and sometimes even the financial mechanisms sustained by the very actors of colonialism in the past. How do you position yourself in relation to this inevitable passage through the colonial gaze?

JG: When cultural anthropology emerged, it carried a particular gaze—as the stepchild of colonialism, it remained part of the imperialist mechanism. But with what we might call the third generation of anthropology, the dialogue shifted. I would say the sense of displacement deepened; it could no longer be divided into something as simplistic as black or white. I believe that history writing incorporates all these different vectors. We also cannot ignore local history. The grandfathers and grandmothers in the Congo who lived through that period would relate to it in a completely different way.

D: To what extent were you self-critical while working on the documentary? Do you anticipate potential criticisms and work to counter them?

JG: I think it comes back to the idea of dialogue. We consulted many academics, like Ludo de Witte, who was our advisor, and Jean Omasombo, a Lumumba scholar. There was a constant dialogue with my editor, Rik Chabuet, because we worked together on this intense project for five years. There was also the dialogue with In Koli Jean Bofane, to whom I sent versions of the film to see how he related to it; with Eve Blouin, who advised me on things I should change or be careful about; and with Lisa Namikas, who was also a Lumumba scholar. She brought a perspective based on the rarely opened Russian archives, which were looking at things from the KGB’s point of view—how they thought and how they found sources that were very different from those of the CIA.

D: While watching Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, one cannot help but partake in the exhilaration and the hopes of Non-Aligned leaders—hopes that often feel naive in hindsight, knowing what would later unfold in history. As an audience, I believe we are traversed by these contrasting emotions. How was it for you while making the film? Did you also experience a sense of discovery and excitement?

JG: When we went through the footage of the 15th General Assembly, it was fascinating to see all these Non-Aligned leaders speaking out and defending Lumumba—the great absentee. Nikita Khrushchev invited world leaders to discuss decolonization and demilitarization. This had never happened before—it had always been the representatives who spoke. So you have Gamal Abdel Nasser, Kwame Nkrumah, Jawaharlal Nehru; you have Fidel Castro speaking for the very first time. When Castro was thrown out of his hotel, Malcolm X invited him to stay at the Hotel Theresa. On the corner of 125th Street was Lewis H. Michaux’s bookstore, where Malcolm X often gave speeches.

Seeing all those heads of state gathering there, Khrushchev and Kwame Nkrumah meeting Fidel Castro for the first time on the sidewalk—Harlem becoming the center of attention—these were all discoveries for me. Or finding footage of Patrice Lumumba arriving on the jetway and being embraced by his friends—it was such a beautiful moment. At the Africa Museum, I found recordings of the Round Table Conference. It was very long, but on one particular day, you can hear the leaders demanding Lumumba’s release in unison.

D: The involvement of the jazz musicians being used as smokescreen or instruments in the context of the Cold War is a delicate subject, if you consider the segregation and racism they were enduring in the United States. To accept working within the system in order to have a voice is something that still resonates in our times. What were the main angles that guided you when telling their stories?

JG: When Louis Armstrong was sent on his Africa tour, he refused to go to South Africa because he would not play for an apartheid audience. Similarly, Dizzy Gillespie’s statement, “I didn’t go over there to sugarcoat segregation back home,” was very telling.

In Dizzy’s band, I chose to focus on Melba Liston. She was the arranger and wrote music for the Middle East tour. She also worked with Quincy Jones, who famously said they were the “Black kamikaze band” sent to all the friction zones. When Melba Liston joined the band, she was laughed at. She was the one writing the arrangements, and at one point, Dizzy told the others, “You guys should stop laughing and first try to play her arrangements. If you succeed—then we’ll start laughing.” Her presence as a woman in the Middle East was also striking—she became a spokesperson for many women who had questions. We didn’t include it in the film, but there was something particularly fascinating about Melba Liston, as a female arranger and trombonist, even in a mixed-gender band, and as someone who was sort of displaced from the United States and who went to the Middle East.

It’s also crucial to mention Abbey Lincoln, along with Maya Angelou and Rosa Guy from the Harlem’s Writers Guild, who initiated the protest at the Security Council when Adlai Stevenson announced Patrice Lumumba’s murder. I think it is interesting that a woman musician took on that role, and that the film is bookended by Max Roach’s drum opening salvo and Abbey Lincoln’s scream. But we found We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite in the Belgian Archives. That’s where the local translation of jazz in the European context comes into play. The suite being performed in its entirety on national television would never have happened during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. What I find astounding is that this was broadcast in 1964—while there was a genocide happening in the Congo. The scream is part of the performance, but there’s a flip side that’s wiped under the carpet. I think all those things it stands for can also mean the opposite. The closer you get to the truth, the more you have to include contradictions. If you listen well, you have to be open to its complete opposite too, which is not to say that truth does not exist.

D: Aside from jazz musicians, Nikita Khrushchev is also a complex figure to depict, as he might come across as a hero challenging imperialism and the U.S. machinery.

JG: Yes, that’s the major criticism about the film—making Khrushchev look like an idol. But I knew that would happen. From the very beginning, when he arrives at the United Nations in 1959, there are all these people outside shouting “Fat red rat, wanted for murder,” and Hungarians and Ukrainians protesting in front of the building. Even in his memoir, he says that when you make a faux pas, take the wrong fork on the road, history will not forgive you, and the memory will haunt you forever. It’s not very overt; it’s my poetic way of alluding to it, but you see the whirling smoke and these images are from Budapest. With “fat red rat,” the falling star, and a quote featuring the page number, I’m clearly saying that this person is not a saint but a more complex character. He was part of Stalin’s machinery, then denounced it and released prisoners from Siberia. With the Red Spring, he opened things through international exhibitions and the involvement of the youth. I also think it’s sometimes interesting to tell the story from the villain’s point of view.

D: What about Patrice Lumumba? Perhaps “victim” is too strong a word to describe him, but we don’t get much insight into his personality, especially since he’s forced to remain in a very passive position in the later parts of the film.

JG: We tried to look for more sources, but there isn’t much material that exists. I also wanted to tell Lumumba’s story through Andrée Blouin, who represented a different way of having firsthand access to working with him. He was not given a visa to go to the United States for the General Assembly. If he had spoken there, I think it would have been quite peculiar and remarkable, but the Americans knew that it would have changed the course of things, and maybe Lumumba would have remained in power.

When Lumumba came to the United States to speak in front of the United Nations, he was not allowed to have an audience with President Eisenhower. You always feel that he’s being silenced. He is not present at the Round Table, but he’s much more present in the minds of all the delegates who demand that he be there. He wasn’t present during the Lumumbist movement, because he was already dead. But he stood for something very important.

I don’t want to romanticize him—he was a person with his flaws. He was still very young when he became the premier of such a huge country. He was a beer salesperson. Back then, Primus was associated with Kasa-Vubu, and Polar with Lumumba. You see him distributing beers in the street. During his speech, you hear him include everybody—sisters and brothers, employees and employers, Catholics and Protestants. He had a sense of enthusiasm, but he was not aware of the whole Machiavellian machinery of international politics. He remained friends with Mobutu to the very end, but Mobutu was pushed into this whole machinery of divide-and-conquer and getting rid of Lumumba. Maybe it would have been different if Lumumba had had more Belgian advisors. Tshombé had a whole committee of advisors. Kasa-Vubu had lawyers and Belgian advisors. Lumumba, of course, had Andrée Blouin. But when you read the memoirs, every day when she came into Lumumba’s office, there was a guy from the Secret Service stealing documents. So, he was up against an entire machinery that made sure he was doomed.

D: Before we finish, I’d like to briefly ask you about the conspiratorial aspect of the parts surrounding Lumumba’s death. The tone of the film shifts dramatically—especially with the music—almost taking on the feel of an investigative thriller. I remember you mentioning North by Northwest (1959) as one of your interests. I’m curious to hear how you decided to employ this specific narrative approach.

JG: I see that you did your homework! Things fell into place because the music played an important part as both a protagonist and a historical agent. So, we gave it a sort of podium, which I think it rightly had at that time. I also included page numbers for all the footnotes, which is something I’ve never done before and have never seen in another film. You see all the footnotes over the course of the film, while it’s nearly edited like a feature music video. So, all these genres clash. For me, each documentary is also about questioning the language of how you’re going to tell a story specific to that subject matter. There’s the Vertovian approach, but then again, it’s mixed with the Eisenstein movement of dramatizing history. They embody different perspectives, but they also help capture the emotional connectedness.

There’s always the risk of falsification, but you can’t avoid including the poetic space because you use words that are embedded with meaning. I hope the film is transparent enough to make it clear that it’s not a falsification. Double Take also had a similar perspective—it takes some time before you get into the film because you have to understand the vocabulary and how the story is going to be told, which is again a Vertovian way of making the one who frames be framed as well. Even on a subliminal level, I try to make that transparent. But I can be criticized for that as well, for falsifying history.

There are a lot of questions you could ask, like: What is history writing? What is the style of writing history or the way you connect and collect certain facts? I’ve tried to be very cautious since one can get very close to the territory of appropriation. It’s always difficult to navigate through this process and try to remain truthful. This was the reason I chose to include the footnotes—because I knew that I would be grilled. But now, at least, if people want to explore it further, or if they say, “I don’t agree with what you said,” the references are there, so we can open up a dialogue.

This piece was first published as the cover feature of the Spring 2025 print issue of Documentary, with the following subheading: Belgian documentarian Johan Grimonprez expounds on the dialogues in his latest triumph, Soundtrack to a Coup d’État.

Öykü Sofuoğlu is a Turkish film critic, translator and PhD student based in Paris. Her writings on film have been featured in publications such as MUBI Notebook, In Review Online, and Senses of Cinema.