With the festival circuit continuing to reclaim its preeminence in the in-person space—and opening up its virtual space to the stay-at-homers—the final third of the year, known to the cognoscenti as Awards Season, roared into being like it was 2019. With the power quartet of Telluride, Toronto, Venice and New York reclaiming September—along with the formidable nonfiction troika of Camden, Gotham Week and Getting Real—the cinema world was chasing the COVID clouds away.

The Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) returned to its full glory, and although I caught the coronavirus there, my inaugural visit to that tentpole confab reopened my heart to the wonders of big-time cinematic happenings. The documentary offerings, served up by the ubiquitous international impresario Thom Powers and his team, set the stage for an autumn of intensified discussions. And the Documentary Day that rounded out the five-day TIFF Conference complemented the screenings with a series of provocative conversations.

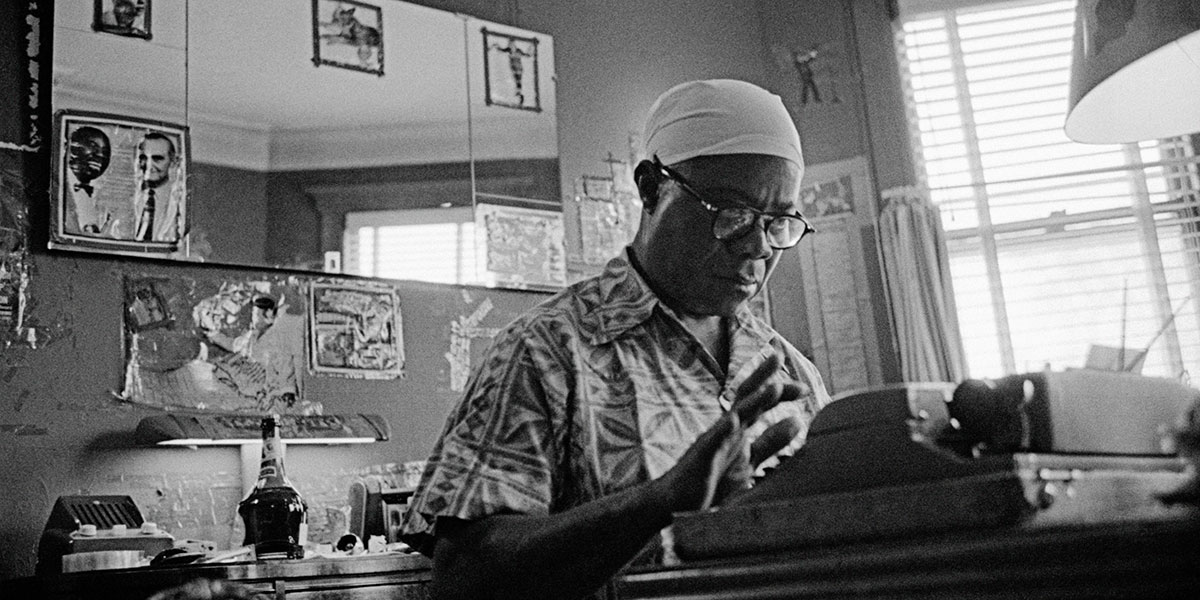

Sacha Jenkins offered up a deeper appreciation for the great jazz artist Louis Armstrong with his Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues. Rather than a cavalcade of experts, contemporaries, and artistic progeny testifying to his genius—although Jenkins does offer some of that here—the filmmaker accesses a trove of audio recordings that Armstrong made—not of his music, but of his musings about race, racism and his role as an icon in addressing both. Often maligned for his seemingly accommodationist posturing and for being out of step with the fervor of the civil rights and Black Power movements, Armstrong expresses his frustration and dismay with his own struggles to navigate the white world, who accepted him as an entertainer, and the Black world, who all but dismissed him for his seeming aversion to channeling his popularity into activism. And while he openly challenged the Eisenhower Administration during the Little Rock Nine crisis in 1957 and questioned his ambassadorial role in promulgating democracy under the aegis of the US State Department when his own country wouldn’t accept him fully, it wasn’t enough. And it took its toll, as articulated in a clip featuring Ossie Davis, who related an anecdote when the two of them appeared in a film. Davis caught Armstrong alone, enveloped in reflection, anguish and deep hurt. As Davis related, “What I saw in that look shook me. It was my father, my uncle, and myself down through the generations doing exactly what Louis had to do for the same reason—to survive. I never laughed at Louis after that.” As Jenkins shared in the Q&A, “I feel like he co-directed the film. He knew it was important for people to understand his story, as an example of how we have to code-switch.”

In an excavation project of a little-known era in American sociocultural history Casa Susanna, from Sébastien Lifshitz, takes viewers back to the 1950s and 1960s, when, in the backdrop of a harshly anti-LGBTQ+ climate in America, a group gathered in Upstate New York once a year to essentially be themselves—cross-dressing men and trans women. In a time when the communication and transportation infrastructures were decades away from the instantaneous, high-octane multitudinous platform apparatus we take for granted today, it’s a wonder that this community maintained and sustained itself as a necessarily underground corps—one that nonetheless reached as far as Australia through its samizdat-like publications.

In an excavation project of a little-known era in American sociocultural history Casa Susanna, from Sébastien Lifshitz, takes viewers back to the 1950s and 1960s, when, in the backdrop of a harshly anti-LGBTQ+ climate in America, a group gathered in Upstate New York once a year to essentially be themselves—cross-dressing men and trans women. In a time when the communication and transportation infrastructures were decades away from the instantaneous, high-octane multitudinous platform apparatus we take for granted today, it’s a wonder that this community maintained and sustained itself as a necessarily underground corps—one that nonetheless reached as far as Australia through its samizdat-like publications.

And it’s also a wonder that Lifshitz was not only able to track down the survivors of this intrepid movement but find footage and stills of what was potentially damaging and career-ending to the participants, had word gotten out. The eponymous Casa Susanna—named for one of the group members—is now an abandoned, dilapidated structure that nonetheless holds lots of memories for the survivors who visit and behold it. These were pre-Stonewall trailblazers, who took tremendous risks to pursue their truths—all the while under deep cover when mobilizations and movements were difficult to undertake, and a robust ecosystem—be it academia or the punditry/journalism/nonprofit space—that would foster conversations about LGBTQ+ culture and instigate activism and change was just not there. Kudos to Cameo George and her team at American Experience for taking this documentary on.

While in Algeria visiting a museum, filmmaker Mila Turajlić happened upon a trove of footage and still photographs of Algeria’s war for independence from France. And this footage happened to have been created by a compatriot from her native Belgrade: Stevan Labudović, whom Yugoslavian leader Josip Broz Tito had dispatched to capture the struggle and create newsreels to promulgate around the world. And so began Turajlić’s quest to discover more about this unknown chapter in anti-colonial cinema and the artist who was largely responsible for it.

She tracks down Labudović, still lucid and feisty in his late 80s, and he regales her with tales from the warfront, in which he had embedded himself with the Algerian National Liberation Army. The footage, in an archive vault in Belgrade, is in pristine condition, as if he had just shot it yesterday, and he has a story to tell about every frame. He is a beguiling raconteur, historian, artist and craftsman—he even chides Turajlić about the dirt on her lens and proceeds to clean it while she’s filming. The two establish an engaging rapport—mentor and mentee, wise elder and whip-smart up-and-comer.

Ciné-Guerrillas: Scenes from the Labudović Reels comes full cycle when she and Labudović return to Algeria, where, at the museum where Turajlić’s film begins, he is feted for capturing history so future generations could appreciate their emergence from the shadows of their colonial past. “I know what occupation means,” Labudović tells his audience, having lived under Nazi occupation during World War II. “Freedom needs to be fought for.”

Labudović died in 2017, and Turajlić spent the next five years making Cine- Guerillas, tracking down NLA veterans, journalists and activists from that period. The resulting film affirms not only the essentiality of history as a discipline but the power of empathy and collaboration in the hands of those who document it.

As journalism teeters on the brink in many so-called democracies around the world, filmmaker Vinay Shukla spotlights India’s NDTV, one of the last bastions of independent reporting in an increasingly hostile media environment, and its heart and soul, Ravish Kumar, a fierce advocate for facts, principles and accountability. While We Watched has the brisk, bracing pace of breaking news, as Shukla and his crew take us inside the newsroom, out in the field, and to Kumar’s home as he struggles to maintain a familial equilibrium amidst the twin pressures of budget cuts and vindictiveness from Prime Minister Modi’s base.

While the story centers around NDTV, While We Watched could easily be replicated in the US, with its Fox-led phalanx of far-right fanatics spewing vitriol night after night. And while NDTV struggles amid layoffs, departures and death threats, Kumar maintains his confrontational cool as a crusader for truth--on the air, in lecture halls and on the streets. This is someone who truly cherishes his work and his profession, as borne out in his commitment to mentoring the next wave of journalists to keep this fundamental tenet of democracy alive. While We Watched earned an Amply Voices Award at TIFF.

Vinay Shukla participated in Documentary Day that week, along with such luminaries as Laura Poitras and Werner Herzog. The latter, a newly minted octogenarian, came to TIFF with his latest film, Theater of Thought, an exploration of the human brain. His feverish curiosity ever on display, Herzog queried about his film,“Why do we accept cultural norms? How do we shape our memories? How do we understand the mystery and agony of love?” Scientist Rafael Yuste, who participated in the film and on the panel, explained about the title of the film, “We’re finally understanding how the brain works: As a theater of thought, as a VR model of the world.” Herzog shared, “I hate self-reflection; there are essential things I’m mystified about. [In this film] we are looking into what constitutes humanness.” With one of the participants in the film, Herzog asked, “Would you like to communicate with a hummingbird?... And he responded, ‘I would love to dance with a hummingbird.’ And he starts to dream. We look into his soul. You don’t need to make any other declaration.”

Theater of Thought, which, full disclosure, I did not see, could very well be a companion piece to Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot (which I did see), from the South African multimedia artist William Kentridge, who, in a delightfully mischievous way, explores the mysteries of his own creative process. “The film started as a COVID project, with a few collaborators,” he explained in introducing the screening. “I thought of drawing as a way of thinking through the project.” The film—and what TIFF showed were excerpts from a nine-part TV series—is largely a conversation with himself, in which different versions of Kentridge manifest themselves in the same frame. Sometimes the conversation between the Kentridges—seated on opposite ends of a table, pacing around each other in contemplation—is an intellectual quarrel, sometimes a mutual exploration, sometimes a genial spar, sometimes a philosophical musing: “Can you see what is absent?... What does randomness tell us?... How do we know our place in the world?... What makes the self?...”

And as his creations—drawings, sculptures, dances, monologues—evolve and emerge, with a little help from his friends as well as his doppelgangers, we appreciate the messiness and frustrations that go hand in hand with the joy and wonder of creating something new, that might answer your questions, but more so, pose new ones. Kentridge alludes to mirrors and windows throughout the film, and both can be deployed as how we create—and, as viewers and end-receivers, how we engage in art. Perhaps it starts with a mirror and becomes a window, or perhaps it's a morph of both In any instance, it begins with blankness and emerges as something that is not necessarily complete, but as its own open-sourced entity for audiences to behold as their own.

As the final film in my 2022 TIFF experience, Self Portrait as a Coffee Pot catalyzed so much about the wonders of cinematic engagement and the discourses that continue well past the theater is cleared.

Tom White is the editor of Documentary magazine.