Heiny Srour’s The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived makes no claim of neutrality. Shot in 1971, but taking three years to finish before debuting at Cannes in 1974, the film documents the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf’s struggle to emancipate the Gulf from its tyrannical, Western-allied leaders. Focusing primarily on Dhofar, an area in Oman that the Dhofar Liberation Front aimed to liberate from the rule of corrupt Sultan Said bin Taimur, the film uses archival footage and charged voiceover to contextualize the pseudo-independence granted to the Gulf region. The Hour of Liberation clearly sides with militants fighting against a coalition of regional and Western forces to create a self-sufficient society based on communist and anti-imperialist values.

One of the film’s most striking elements is its grounding of the struggle in the political economy of colonialism, adopting a Marxist as opposed to a culturalist or nationalist framework. A fiery dual-narrator voiceover accompanies the footage, offering a radical take on the unjust distribution of resources, oil extraction by colonial powers and their local allies, and the futility of a national independence that does not remedy the confluence of capitalist and extractivist practices.

The film takes its name from a song that feels more like a chant and which punctuates different moments in the film: “People of the Gulf, / beware of the neocolonial plot called the United Emirates. / These puppet rulers act against your interests. / One word from Britain and they obey like slaves.”

Srour is best known for her two feature films, The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived (1974) and Leila and the Wolves (1984). The half-Egyptian, half-Lebanese filmmaker grew up in Lebanon, studied sociology at the American University in Beirut, and then moved to Paris to pursue a PhD in anthropology. During this time, she started working on The Hour of Liberation. Her presence in Paris gave her access to funding and later restoration support in France. Leila and the Wolves was made when the director was living in the UK, but was also restored in France.

The difficulty of securing and restoring these films reveals the complex political economy of audiovisual preservation—a process that raises uncomfortable questions about whose work gets saved, who does the saving, and the neocolonial dynamics embedded in these “rescue” efforts.

***

I first heard of Heiny Srour when I, like many others of my generation of Arab film professionals, became interested in connecting with our cinematic elders. My friend and longtime collaborator, Mary Jirmanus Saba, introduced me to Srour’s films while she was working on a cinematic work of speculative history that reinserts women in the very male-centric canon of militant and third world cinema. From the Afro-Asian Film Festivals to congregations of third world filmmakers in the ’60s and ’70s, Saba asks, “Where are the women?” Srour’s The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived heeds the call.

With this documentary feature, Srour was not only the first woman from the region to have a film at Cannes, but also one of the few women filmmakers who asserted their presence in an overwhelmingly male-dominated canon of militant cinema.

Srour, who never received formal training as a filmmaker, instead cites the Beirut Cine Club as her only film school. “I knew cinema was my medium when I watched Fellini’s 8 ½ at the Beirut Cine Club,” she tells me. I was not surprised. Her playfulness and fluency in different cinematic registers come across in her two drastically different feature films. Whereas The Hour of Liberation is often described as a militant film, Leila and the Wolves is something else entirely—a formalist, genre-bending work that departs significantly from the aesthetics of militant cinema yet remains committed to Srour’s anti-imperialist stance and feminist politics.

As curators and film scholars, some of us often shy away from confidently describing historic works as “firsts.” With perpetual cycles of cinematic rediscoveries and the many gaps that interrupt film history, especially from the Global South, many “first” labels await revision. Srour, however, isn’t shy about claiming firsts. She describes The Hour of Liberation as the first film in the Middle East to give “voice to the voiceless.” When she set out to make this film, few regional documentaries used sync-sound cameras. The technology was not easily accessible for many filmmakers during the ’60s and early ’70s, but Srour insisted. Her training in anthropology made her aware of these politics of representation, particularly regarding longstanding ethnographic traditions wherein subjects were never really allowed to speak.

Female VO: Weakened, Britain evacuated its base in 1971 to the North of the Gulf and left them to the U.S. A false independence was granted to the region.

Male VO: Flag, constitution, parliament: all empty shells. Such was the independence given by Britain to Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

Heiny Srour. All following images and stills courtesy of Several Futures

The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived.

The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived.

The Hour of Liberation departs from earlier documentaries relying exclusively on voice-of-God commentary. Though it uses voiceover, it also records numerous conversations in which subjects speak for themselves. The voiceover is militant rather than ethnographic—not seeking to analyze, represent, or describe cultural practices as exotic, but in and of itself a call to militancy. Before sync-sound technology, documentary subjects were portrayed as silent, passive, spoken for or about. Many filmmakers of Srour’s generation shared a similar sentiment. Although The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived might not be the absolute first, it’s certainly one of the earliest regional feature-length documentaries to allow its subjects to speak for themselves.

Unlike early ethnographic films claiming singular authorial points of view, Srour emphasizes the value of collaboration. She believes that without support from other comrades, militants, and colleagues, the film would not have emerged as it did. After restoring the film in 2014, she created another version in 2019 with an updated introduction and more detailed credits. “The end credits are so long, but I insisted that everyone should be thanked so that people understand that a militant film is made with the help of other militants, and the help of people who sometimes risk a lot,” she says.

She credits the Iraqi Student Society (mostly students exiled from Iraq who collected donations) and the union of workers from South Yemen (who used to donate one week out of their monthly salaries to help her finish the film). “Had these students been caught fundraising, they would have risked being deported from France, and it would have been from the airport to the torture chamber. It was a big sacrifice,” she says, with sincere appreciation.

I used to attend festivals for ethnographic film, and usually, they film the people of so-called primitive societies like insects. In this film, I am proud to show that even a society that lives in the Stone Age has the same need for democracy, feminism, and dignity.

Heiny Srour

The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived.

Another key support figure was Tahar Cheriaa, a leading figure in Tunisian cinema and founder of the Carthage Film Festival. Cheriaa held a position in the French Agency of Cultural and Technical Cooperation (Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique). When Srour returned to Paris, unable to finish editing due to a shortage of funds, Cheriaa offered support through the agency, but with one caveat. “He told me you need to change the name of the film to a more anthropological title” to be eligible for funding, Srour recalls.

Srour and Cheriaa capitalized on the seemingly “primitive” shooting location while also recognizing The Hour of Liberation’s decolonial potential as an intervention in ethnographic representation politics. “I used to attend festivals for ethnographic film, and usually, they film the people of so-called primitive societies like insects. In this film, I am proud to show that even a society that lives in the Stone Age has the same need for democracy, feminism, and dignity,” Srour says.

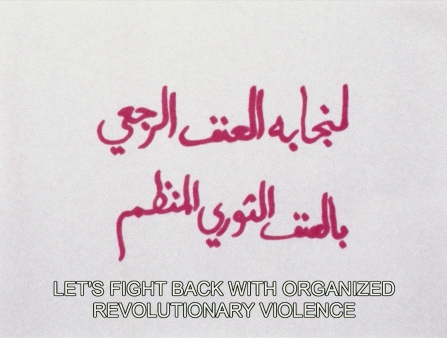

Above all, The Hour of Liberation belongs to the canon of militant cinema, a tradition of filmmaking that Srour defines as films that seek to push audiences into action. “Militant cinema was summed up by the opening sequence of The Hour of the Furnaces (1968) by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino. Every spectator is a traitor. You are not here to witness history, but to push the big wheel of history forward, otherwise you are traitor,” she asserts.

Her film achieved exactly that. When screened in France, a scene showing medication shortages in Dhofar prompted audiences to fundraise and donate bags of medicine. This is what militant cinema does, she tells me. Reflecting on the question of whether we can find examples of militant cinema in the present, Srour answers that “militant cinema as such does not exist really—it’s very rare to have a film which is trying to push you into action.” Srour emphasizes that this impulse towards militancy does not really exist anymore due to the global decline of the left.

Her film is neither a call for aid nor a fundraising campaign. It is not a plea for alleviating the suffering of a disenfranchised, helpless other, or an attempt at humanizing subjects by perfecting their victimhood to appeal to (often Western) viewers. As a leftist, anti-imperialist cinema, it brings about collective action supporting armed resistance. Subjects appear neither helpless nor victimized but heroic—examples of what anticolonial resistance and self-determination movements can achieve. Unlike contemporary social-issue documentaries stopping at viewer sympathy or awareness-raising, militant films seek radical change and inspire comradely congregation through leftist politics, which situates the issue at hand within broader power struggles, capitalist exploitation, and imperial legacies. Such a stance is neither liberal nor humanitarian; it is instead a radical political position that comes across in every word uttered and every frame captured in the film.

***

Leila and the Wolves.

Srour’s second feature, Leila and the Wolves, demonstrates her political and stylistic fluidity. While never abandoning her political commitments, she experiments with cinematic potential. Whereas The Hour of Liberation hews closely to documentary conventions, Leila and the Wolves departs significantly from classic documentary. Even with the rise of hybrid cinema, documentary reenactments, and elevated sci-fi, Srour’s second feature still feels unclassifiable. Leila and the Wolves is historical fiction with surrealist elements, clear Brechtian influence, and almost theatrical acting that moves back and forth in time, defying linear conventions and historical teleology.

The protagonist Leila—first seen in an art exhibition in Beirut conversing with a man skeptical of women’s roles in regional liberation movements—travels back in time to show the active participation of Palestinian and Lebanese women in anticolonial struggle. The film swiftly moves among different visual styles and historical moments, mixing archival footage, documentary-style reenactments, and visually stunning surrealist scenes.

Although the film departs significantly from the documentary aesthetic of The Hour of Liberation, anticolonial struggle and women’s roles in emancipatory movements continue. Srour describes this as progressive, as opposed to militant cinema. “A progressive film helps you look at the world in a critical way… should help the viewers pause and think about the way history is told, because history is so distorted.”

Shot in Syria and Lebanon, this was Srour’s first experience working with actors. Funding remained an issue. “When you don’t have enough money, you have to give orders and you ask people to obey because you don’t have the time to repeat, rehearse, or give the actors enough time to really get inside the roles, and I really suffered from having to do that.” Despite limited resources, Srour was able to complete the film with help from colleagues such as Syrian director Omar Amiralay, who supported Srour during the shoot in Syria. Upon its completion, it “was too avant-garde for Cannes. It was screened on the British Channel 4 and was very successful,” she proudly elaborates. After its restoration, the film was screened at Venice, Edinburgh, and festivals worldwide.

When I asked how she managed to make such different films and whether one was closer to her heart, she responded with an anecdote: “In Croatia, they told me it’s as if it is not the same filmmaker who made both films.” She elaborated, “You must renew yourself; as a filmmaker, you shouldn’t stay the same but change radically from one film to the other.”

Beyond these two features, she only made Rising Above: Women of Vietnam (1995, 50 minutes) and The Singing Sheikh (1991, 11 minutes). The latter focuses on Sheikh Imam, an Egyptian singer whose frequent collaborations with Egyptian poet Ahmed Fouad Negm made the duo key figures in the history of Arab music in general and among leftist and revolutionary movements specifically. Srour is still trying, to this day, to secure funding to expand this short into a feature.

The difficulty that a filmmaker with as much talent, craft, and love for cinema faces securing support for a dream project about one of the most important icons in leftist cultural production attests to the brutality of cinematic infrastructures of financing, production, and exhibition. Although luckier than many Arab filmmakers whose films never got a chance at restoration, finding and restoring both The Hour of Liberation and Leila and the Wolves was quite challenging.

Leila and the Wolves.

Srour is key to Arab cinema generally and the Arab documentary tradition specifically. Documentary filmmaking in the Arab world has a long and rich history but with many gaps—films lost, filmmakers forgotten, archives rarely rescuing, and on the rare occasions when they are, often located in countries inaccessible to many of us. Arab passports are suspect; visas are granted to a select few. Our cinematic heritage exists as fragments in distant institutions. While lacking well-kept national archives can be frustrating, it also incentivizes continued searching through unconventional routes and informal networks.

Srour expressed immense gratitude to all the individuals and institutions that helped her find and restore prints. These efforts helped save the memory of a people—those who fought to liberate Dhofar and had ambitions to liberate the entire Gulf region. Losing the film would have meant losing the only record of this movement.

Even Cannes recognition didn’t protect Srour’s films from audiovisual preservation politics or precarious print fates as the world transitioned from analog to digital film production and exhibition. While searching for Leila and the Wolves wasn’t straightforward, it wasn’t as complicated as The Hour of Liberation. Shot on 16mm, when the negative was found, it reeked of vinegar—a fate that happens to uncared-for, improperly stored celluloid. Unless prints are stored in well-equipped rooms with proper temperature control, vinegar syndrome can destroy them—a common problem for filmmakers and film archives all over the world.

Leila and the Wolves was found in the British Film Institute archives. The Hour of Liberation was located in a lab that was sold to another lab (another common problem arising from the digital turn, resulting in many film lab closures and thus print losses). When Srour came to claim the print around 2010, she was told that all the documents accompanying the film were lost, and she couldn’t prove rightful ownership. Only after an old acquaintance who had worked on subtitling the film for Cannes vouched for her did the lab agree to hand over the negative. Beatrice de Pastre, the director of France’s national film institute, Centre national du cinema et de l’image animée (CNC), got involved. “It wasn’t her responsibility,” Srour explains, “but she made this gesture and found everything.” The restoration was finished in 2014.

Srour joins a handful of Arab filmmakers whose work was saved through Euro-American partnerships with Arab film institutions. These Euro-American interventions characterize most Arab audiovisual restoration and preservation efforts. In recent years, films by Youssef Chahine, Tawfik Saleh, Shadi Abdel Salam, and Jocelyne Saab have been given another life thanks to these partnerships.

Even ardent film lovers might mistake audiovisual archiving, preservation, and restoration as noncommercial or apolitical endeavors prioritizing collective film heritage safekeeping. While sometimes true, cinephilic excitement about newly restored films (especially print projections) and the curatorial fixation on rediscovery forces us to reflect on the political economy of such endeavors. There’s a niche but thriving market running on restorations, repertoire screenings, and rediscoveries. Restorations should also be understood as investments or brands expected to yield profits, with their own distribution and exhibition infrastructures laden with inequalities and uneven access to resources.

***

Despite their immense importance to Arab and global cinematic heritage, Srour’s films would not have gotten U.S. theatrical runs if not for these restoration efforts. Similarly, Criterion Collection would not have acquired Youssef Chahine’s work and the New York Film Festival would not have shown Tawfik Saleh’s The Dupes (1972), if they had not been reintroduced to the festival, arthouse cinema, and streaming ecosystems as rescued, restored, or rediscovered.

For Global South filmmakers whose work is often “saved” through Euro-American institutions, this market’s political economy raises many questions: Should we be grateful or resentful toward former and current colonizers saving our films? Should we be grateful when governments financing many of those Western savior institutions directly caused the impoverishment and underdevelopment of the filmmakers’ countries of origins—the same filmmakers whose work they are now celebrated for saving?

One common position is that if these Western institutions don’t do it, no one else will and the films will be lost (because most countries lack resources or the technology for audiovisual restoration or preservation). This can be true, since many films by less internationally visible filmmakers have been lost forever.

Restoration can ensure films retain economic value, reinforcing hierarchies between screenable films and those living only on laptop screens.

But it is important to emphasize that often what is lost is a copy of the film ascribing to festival, art house cinema, and streaming platforms standards—a copy screenable in formal exhibition contexts. Perfect or near-perfect quality is a condition for international visibility and circulation. Online and in informal settings, things are a bit different. There, Srour’s Hour of Liberation and Leila and the Wolves were never truly lost. Many of us have seen them online decades before their restoration, such as with Youssef Chahine, Shadi Abdel Salam, and Jocelyne Saab. Of course, watching recently restored films on the big screen satisfies cinephilic impulses in ways that low-quality digital copies never could. However, there is still joy in detective work that goes into finding and watching these copies. The two modes of viewing do not cancel each other out.

There are two rescue modes: one feeds the capitalist wheel of global film exhibition, and the other defies commodification since no one would buy, sell, or distribute digital files ripped from VHS tapes and further compressed for YouTube upload. Established film festivals, archives, and institutions, especially in the West, would rarely accept such low-quality files in their screening spaces.

In Cairo, I was able to screen a collection of short films by Egyptian filmmakers working in the 1970s. The films were given to me on a USB stick and I made the controversial decision to show the films as they are, because otherwise, audiences would not have a chance to see these films on a big screen. The screening sold out, and one of the filmmakers was present for a Q&A afterwards. When a Canadian colleague came to Cairo to search for a copy that he could screen in Toronto, he found that the only copy that existed did not meet Canadian standards. I cite this anecdote to highlight the problems of the savior discourse, which partially emerges from universalizing a certain standard that dictates which films can and cannot be shown.

Many films are not saved from vanishing. They already exist as low-quality internet copies, on VHS tapes, hard drives, and DVD collections. Restorations are interventions prolonging the life of a film as a commodity. They are efforts to ensure that screening copies remain in festival, streaming platforms, and formal exhibition circulation. Restoration can ensure films retain economic value, reinforcing hierarchies between screenable films and those living only on laptop screens.

Heiny Srour in March 2025 at BAM in Brooklyn, NY. Photo by Kholood Eid

Instead of uncritically celebrating recent restorations or lamenting the absence of film archives in the Arab world and the Global South, taking it as a sign of backwardness, this developmentalist discourse, where the rest tries to catch up with the West, needs interrogation. And as we celebrate the new (formal) life given to Srour’s films, it is important to remember that informal networks and amateur efforts have also given many films (including Srour’s) a second life with a much wider geographic reach. These films’ accessibility to viewers who will never access Cannes or Criterion Collection expands the life of films beyond the complicated, neocolonial relationships characterizing many Western institutions’ rescue efforts to “save” cinema from countries presumed to be still lagging behind.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Summer 2025 issue.