Dawson City, Frozen Time. All images courtesy of Bill Morrison

Few filmmakers have as recognizable a style as Bill Morrison. Those with even a passing familiarity with his work will think of degraded film stock, an aesthetic of cinematic ruination. And in film after film, reviewers invariably use the same words: spectral, haunted, fragmented, poetic. This reputation may give the impression that his work, for all its beauty and mystery, is fundamentally repetitive, a mere cycling of similar ideas and feelings.

It is almost as if Morrison foretold this reputation during his first feature, Decasia (2002), the film responsible both for his renown and the caricature that has come with it. Composed of decaying nitrate film stock, the film is an elliptical meditation on mortality, on the overwhelming beauty and melancholy of loss. In the opening fragment, we see a whirling dervish from the early twentieth century; in the next shot, we see a row of film reels all turning in synchrony. Viewed only on the physical plane, both instances may seem repetitive and inscrutable. But this simple spinning, Morrison suggests, can also generate the plenitude and profundity of human experience.

The dervish is an apt metonym for Morrison’s career: he has been engaging in the same form of dance, spinning around the same themes, histories, archives, and even footage, repeating similar gestures again and again. Yet this is not to say that each turn is redundant. Rather, each repetition accrues new meanings. And like the spinning of the dervish, his work rarely feels static or rote—there is a dynamo that electrifies the films.

But how wide, exactly, is the arc of this dance? Particularly in recent years, Morrison’s style has been shifting in surprising ways. His recent austere short on police brutality, Incident (2023), was a surprise winner of Best Short Documentary at the 2023 IDA Documentary Awards—a far cry from his abstract beginnings. And this spring, Morrison had retrospectives of his work at the American Cinematheque’s This Is Not a Fiction festival and the Metrograph. The latter, a thoughtful selection spanning from his delightful The Film of Her (1996) to Incident, offered an opportunity to review his ambit. What emerges is a trajectory that is imperfect, for as Morrison knows well, perfection implies completeness, which is to say, stasis and death. And Morrison’s style is very much alive.

***

In interviews, Morrison has dated his interest in making films to seeing Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi in the theaters in 1982. It was, he explained, a watershed moment in which he realized cinema need not have a narrative structure, that it can instead develop through association, feeling, and experience. Reggio would go on to become a close friend and supporter of Morrison’s work, serving as a producer on Decasia. The two shared not only an interest in working with music and associational editing, but also an abiding fascination with capturing the natural world.

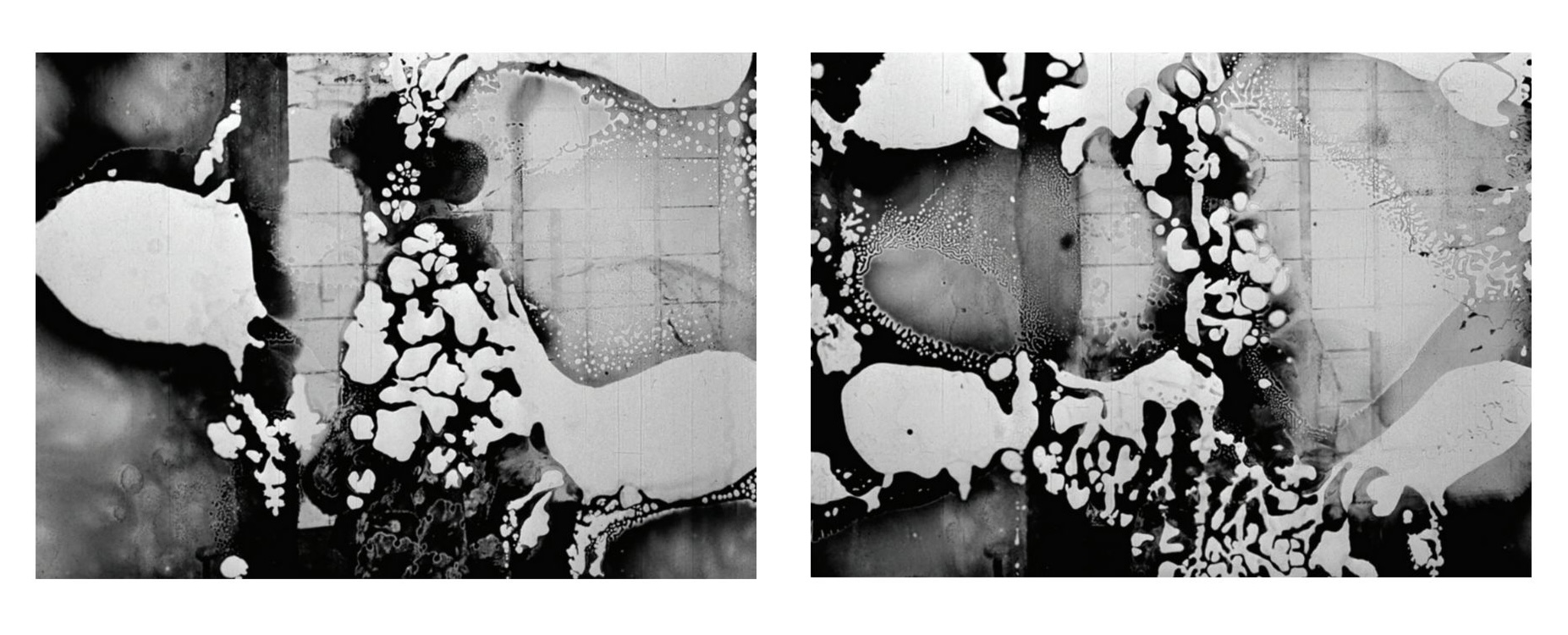

It’s a revealing relationship, but less for what they had in common and more for what Morrison's differences reveal about his radical style. For if films like Koyaanisqatsi seek to capture the beauty and human depredations of the environment, Morrison is working instead with the fundamental elements of nature, having it structure the very foundations of his films. In Decasia, for example, Morrison literalizes this through his selection of degraded films: water laps around a rocky outcropping as the film pulses and smears and bleeds as though it were itself one with the water; ethereal mist is shrouded by the mist of moldering film; microscopic animals wriggle on nitrate that appears eaten by termites; a Monarch butterfly’s patterns are echoed in the very medium capturing it.

Degradation in film, after all, is always a story of the environment. For celluloid, time and the environment are part of a single continuum, like spacetime in physics. Decay does not tick steadily with a clock, but bends its shape to temperature, its life measured by its gasses and acids, by its proximity to heat and the eruption of instantaneous conflagration. We are sensing time on a scale beyond the bounds of the human. These images of loss give us a glimpse of what it might be like to exist in a different, elemental temporality; his films create a sensation of a geologic or glacial time.

Morrison treats ruination as though it were a creative collaborator. In his earliest films, when he was at New York’s Ridge Theater in the ’90s, he had painted on archival film, but by the time of Decasia, he had begun to allow decay to do the painting. Morrison’s work is not mere celluloid ruin porn. Rather, it gives the impression that decay is uncannily animate: a boxer fights a cascade of rot; a campfire erupts into pulsing licks of decay, consuming those around it by its eerie glow. It is as though this force of ruin were trying to speak to us.

What exactly it wants to tell us, however, is never made totally clear. There is no Ouija board that can give us a definitive message. Instead, we must rely on the subtle feelings it evokes. And it is in this area that Morrison is an unparalleled guide. To go through Morrison’s oeuvre is to become alive to the many experiences possible in decay. In his magnificent short, Who by Water (2007), we see a series of portraits (some candid, some posed) of passengers preparing to embark on a ship. As we watch them, the film stock’s subtle damage becomes increasingly conspicuous. Although restrained by Morrison’s standards, mostly streaks and flickering spots, it increasingly feels like a barrier between us, like looking through a dirty windowpane.

Accompanied by Michael Gordon’s unnerving score, the film becomes increasingly unsettling. The passengers’ fate on the sea is theirs alone. We can watch but not intervene; whatever tragedy will befall them is now irrevocable. By the time the film ends, I scoured the credits to see which tragedy this footage preceded: Was this the maiden voyage of the Titanic? Were they on the final voyage of the Lusitania? But no, it is simply footage culled from Fox Movietone Newsreels. “Who will perish by fire and who by water?” Morrison doesn’t tell us. We may think we can watch fate unfurl from a safe vantage point, but this is only the condescension of posterity. The barrier between us and them is total.

But if Who by Water is asking us to look out toward the sea, his stunning short The Light Is Calling (2004) throws us into its roiling waves. Here, the past is not something we peer at from a distance but is rather a force that overwhelms both viewer and viewed. The film is so damaged we can barely make out the fragments of images: a soldier riding into a village, a woman peering through bubbling nitrate, and a heart-stoppingly beautiful entanglement between them, as she repeatedly evanesces into the decay. With such compelling images, metaphors seem beside the point, yet it’s easy to see this as a visual embodiment of half-forgotten memories, or of the bewildering power of desire.

Yet it is not so simple. As is often the case in Morrison’s work, there is a final sly twist. The footage is from the film The Bells (1926), in which an indebted innkeeper murders a traveling Jewish merchant, using the money in part for the dowry that consummates the marriage of the two lovers we see in The Light Is Calling. It may feel like a melancholic and sublime love story—indeed, it may be that to the two lovers, and for us—yet there are forces that shape this love that must also be hidden from sight.

This quiet theme of violence—and the way that aesthetic experience can occlude it—has long been a theme running through his work. It comes through most vividly in his medium-length film, Beyond Zero: 1914–1918 (2014), in which the degraded film stock uncannily parallels scenes from WWI. But for Morrison, latent violence is not simply a theme but the very material substrate of his projects. “Film was born of an explosive,” Morrison writes in Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016), and since at least his early work The Film of Her, he has recycled the same footage to recount this history: We see the plantations where Black laborers pick cotton; the manufacturing of guncotton and its use in hand grenades; and finally, the mixing of guncotton and camphor to produce nitrate film. Violence built early cinema.

***

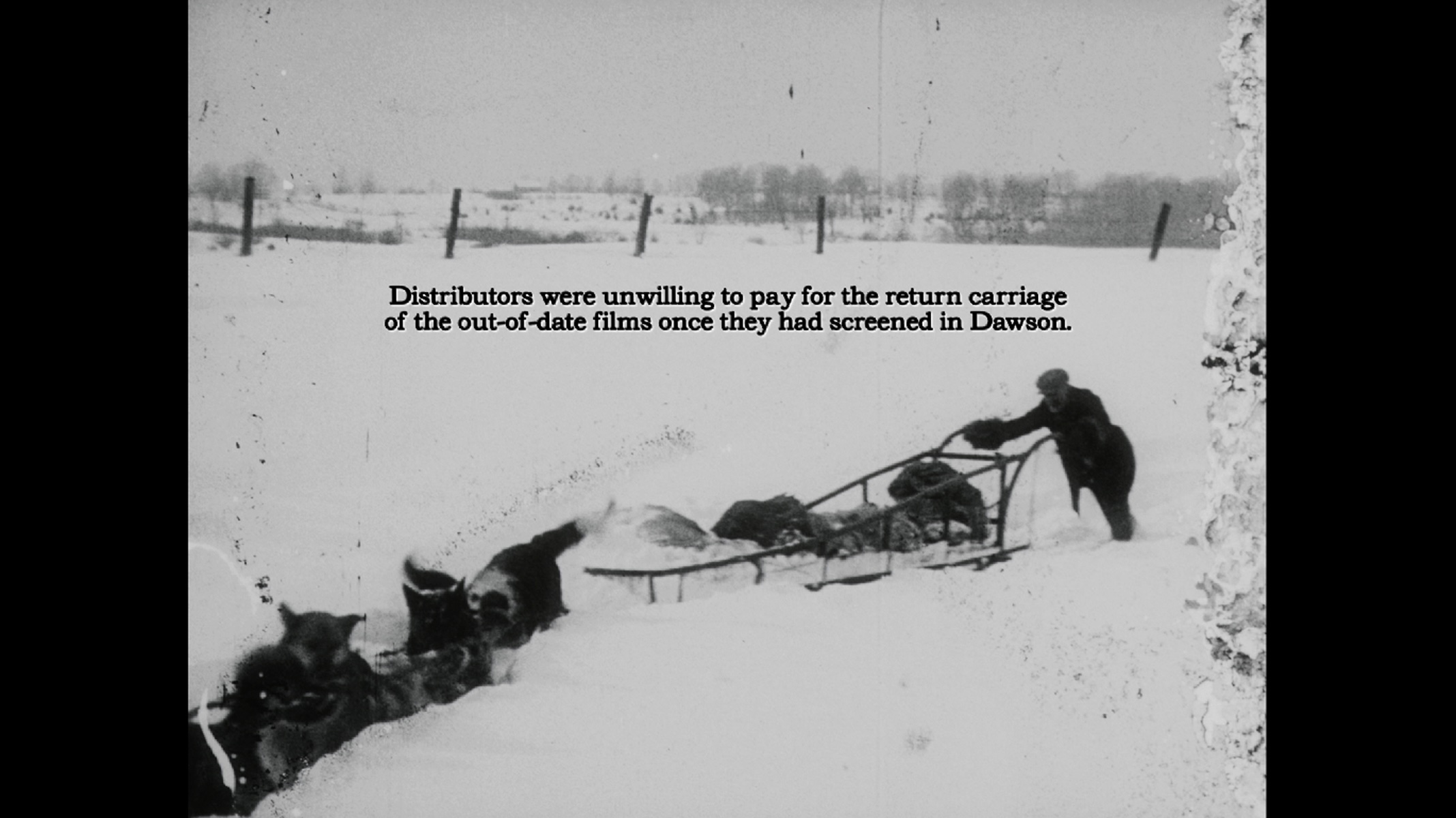

In one of his most widely seen films, Dawson City: Frozen Time, Morrison most directly turned to early cinema’s history from an unlikely vantage point, that of a mining boomtown in the Yukon. The pretext for the film is classic Morrison. In 1978, a Pentecostal preacher and alderman of Dawson City, digging behind Diamond Tooth Gerties Gambling Hall, uncovered a load of 533 reels of film. These films were dregs twice over. They were left in Dawson City as their last stop in their theatrical tour, eventually deemed so worthless that they were dumped into an old pool that needed filling. Whereas nitrate archives like the Fox vault would inadvertently go up in flames, it is in the far north, at the seeming periphery of American culture and capital, that the center is preserved.

But though the film’s pretext fits his usual mode, Morrison’s approach sharply diverges. While his earlier films withhold information and invite the viewer into an associational dream logic, here Morrison wants to give us information. He orders and disciplines the footage, editing it into a chronological narrative, gives us unceasing explanatory texts, and assiduously identifies every single clip with title and date.

One soon understands why he chose to do this. Telling the history of this small boomtown begins to feel like a microcosm for the history of cinema, American politics, and even capitalism itself. We have the history of Indigenous displacement, the capitalist cycles of boom and bust, and the exploitation of labor, as well as the environmental depredations of the extractive economy. But more surprising are the ways that so many strands of history, from the early twentieth century to now, seem braided through this outpost. It is not only the story of early mass film culture (Charlie Chaplin is here, as well as Sid Grauman, the creator of the still-open Egyptian and Chinese movie palaces of Los Angeles) but also the story of the Robber Barons (the Guggenheims visit) and even the Trump family (Dawson City, we learn, was near the origin of their wealth).

It is as if the form of the archive inflects the form of Morrison’s films. Many of his earlier features are built from discrete archives, and their closed and controlled spaces seem to echo Morrison’s highly consistent formal choices. We watch many of his earlier films—such as Decasia, Miner’s Hymn (2010), and Beyond Zero—like a researcher exploring a new collection: a self-contained world of footage upon footage, without much explanation or context. In contrast, Dawson City is far more heterogeneous and expansive. Like the original dig site, in which the film was mixed with chicken wire, bottles, and broken curling rocks, Dawson City incorporates clips from television, interviews, photographs, and newspapers. These archives, Morrison suggests, have their own dramaturgy.

Much of Dawson City appears wildly incongruous next to Morrison’s earlier work. The obsessive local pedantry of the film—chronicling every single nationally known figure to have set foot in Dawson and monomaniacally detailing every vicissitude of the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association—will be familiar to anyone who has visited a small town’s historical society. And this is exactly the point. Morrison is absorbing the way the place articulates its own history. If this interpretation seems like a stretch, he makes this sly, self-reflexive move evident at another moment in his film. Those familiar with his earlier work will likely be surprised to see ample use of the Ken Burnsian pan over photographs. It’s the first and only time Morrison has used this technique, and it gives the film a surprisingly conventional sheen. But, as is often the case with Morrison, style is not a choice but an organic feature of the subject: later in the film, Morrison reveals that Dawson City was subject to the first use of the Burnsian pan, in the influential Canadian filmmakers Colin Low and Wolf Koenig’s 1957 documentary City of Gold. Dawson City—with all its messiness, pedantry, and conventional tropes—is, for these very reasons, a film that is radically rooted in place. It is, both literally and figuratively, an autochthonic history, a film born from the earth.

***

Morrison’s most recent film, Incident, reveals the extent to which he invites the archive and the material to shape his films. Based on footage acquired by journalist Jamie Kalven, Morrison compiles footage from body cams, surveillance cameras, and dashboard cams before and after the murder of Harith “Snoop” Augustus by Chicago police officer Dillan Halley. Even more than Morrison’s stylistic shift in Dawson City, here seemingly none of the trademarks one has come to expect from Morrison are present. Instead, Morrison offers us a simple collection of time-stamped footage, which is often split into four synchronized panels—like a surveillance monitor, or an old first-person shooter—accompanied by captions and explanatory text. There is no trace of the organic feeling of his earlier work. Time ticks by with brutal precision.

The film’s matter-of-fact presentational style might suggest that Morrison wants to repress any trace of himself in the footage. But this would miss what is so singular about Morrison’s work more generally, that his films have always invited the medium to speak for itself, and to speak in a form that is distinctive to it. And indeed, resting beneath the shift in the approach are the same preoccupations that have guided Morrison’s work for decades. His earlier footage of cotton plantations and guncotton and nitrate factories haunt this footage; racist exploitation and weapons have always been part of his story, and here it erupts most painfully. The cameras may be digital, but the material violence of the image is still here, only more cutting. Chicago police are instructed to turn their body cams on record “at the beginning of an incident.” That is to say, these images only exist when there is the potential for violence.

We have all seen these kinds of videos forensically analyzed by publications like the New York Times and Washington Post, with the decisive moment parsed in freeze frames and correlated with different angles. But Morrison, in line with his interest in discarded and ignored footage, gives most of his attention to the periods both before and after. These peripheral moments are particularly revealing of the structure of police violence: Augustus’s friends, neighbors, and acquaintances confronting the cops on the scene, giving voice to life under a de facto police state. Another cop arrives on the scene and refers to Augustus as the victim. The car whisks Halley and his partner away, as his partner manically praises him, narrating a fantasy they desperately need to believe. It is during this last moment that the film also has one of its cruelly uncanny moments. “You good, you good… You are okay, you are okay,” an officer hurrying him away from the scene repeats, while at that very moment across the split screen, we listen as another officer asks indifferently, “Is he [Augustus] alive?” to which the paramedic flatly responds, “Probably not.” As in Morrison’s earlier work, life and death overlap. But while his films had previously felt haunted, here we sense something altogether more monstrous.

The film ends with one last, terrible irony. Officer Halley was cleared of any misconduct in the murder of Augustus. But he was suspended for two days. The reason? Not that he fired his gun too quickly, but rather that he didn’t turn on his body cam soon enough. His crime, in other words, was not in murdering a Black man but in failing to document it properly. Morrison’s theme has always been decay. Here, however, the decay is society’s.

Carmine Grimaldi is a filmmaker and historian.