Editor's note: What follows is an edited version of filmmaker Sam Feder's keynote address at the 2020 Getting Real Documentary Conference. To watch the full keynote and Feder's conversation with Laverne Cox, head to https://youtu.be/rh9EqGfZg_A

I wrote a draft of this talk in which I thanked over 30 other people. But my producers said it wasn't a good use of my time. And since it’s their job to manage my time, I listened!

But acknowledgement is important. In particular, it relates to this year’s themes because who gives us access, how we attain power, and what possibilities come from it all stem from the vital work that is often unseen and unacknowledged. What I’m going to talk about today are three of those unseen practices in documentary filmmaking—compensating protagonists, empowering our crews, and questioning who is in leadership.

For some background, this summer I released the film Disclosure. For those of you who haven't seen it, Disclosure is about transgender representation in film and TV, and how that representation informs what non-trans people think about us and how we think of ourselves. In production we prioritized hiring trans crew, and when we couldn't do that, we mentored a trans person. Over 120 trans people contributed to Disclosure.

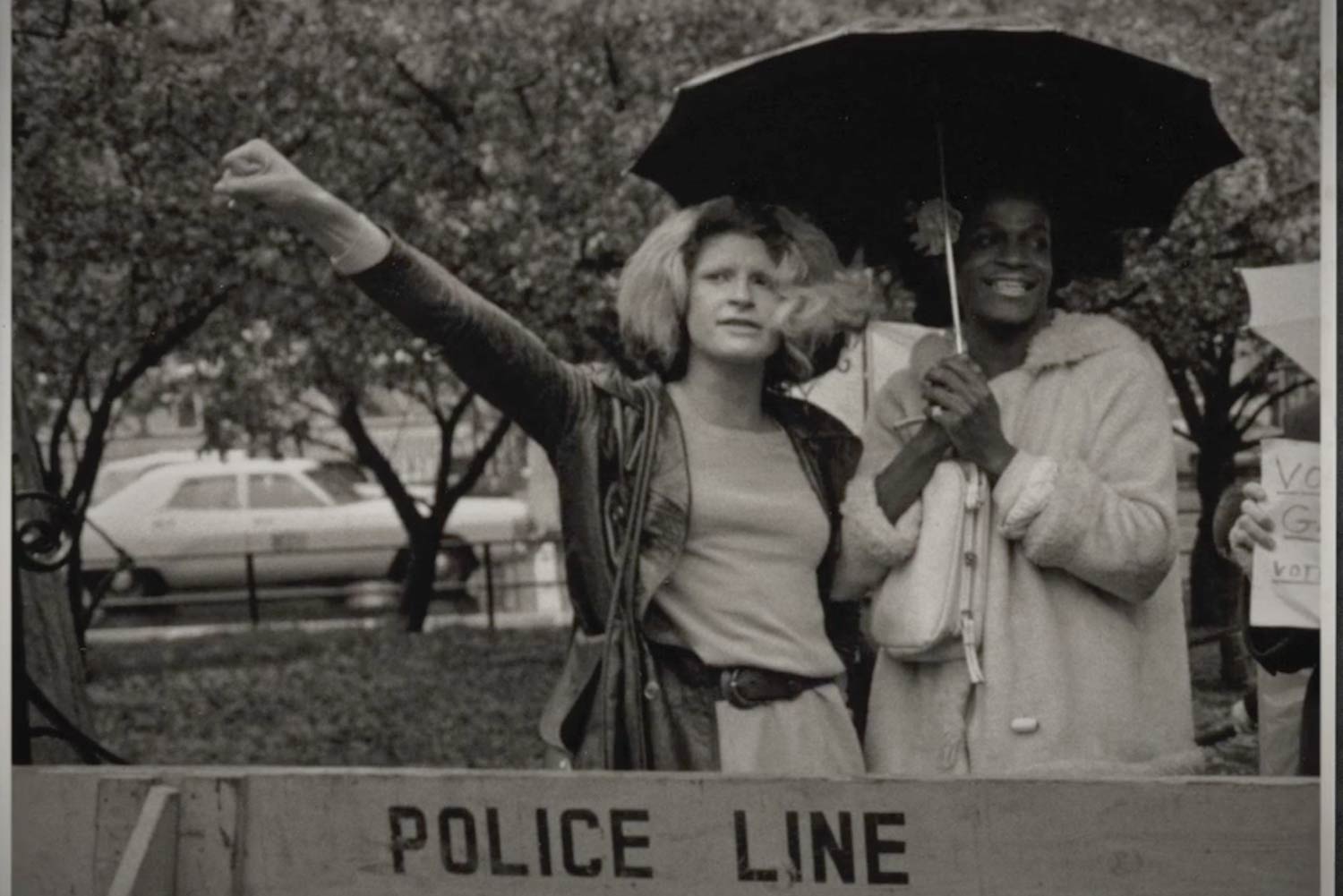

I started thinking about Disclosure shortly after Laverne Cox was on the cover of Time magazine in June 2014. Laverne was the first openly trans woman to ever be on their cover. She wore a beautiful blue dress and looked defiantly down at the camera. The headline read, “The Transgender Tipping Point.” The public conversation at the time suggested that visibility was the singular goal for trans people. And with Laverne on this cover, we had reached the tipping point. Yet the trans people I knew were still struggling to access employment, housing and healthcare. With that paradox in mind, the main thread in Disclosure is about how visibility both opens doors of possibility and can be very dangerous, because we know that when a marginalized community gets mainstream attention, backlash ensues. Suicide rates among trans men has been surging and the murder of black trans women has reached epidemic proportions. So, how can we reconcile these two truths—the celebratory increase of visibility and a rise in social and legislative violence?

There is not a singular cause-and-effect relationship between visibility and violence. But how we see others impacts how we treat them. So, we have to consider the fact that 80% of Americans say the only trans people they know are the ones they see in films and on TV. And these images, over the past century, have been deeply distorted and dehumanizing.

Yance Ford, the Oscar-nominated director of Strong Island, says towards the end of Disclosure, “We cannot be a better society until we see a better society. I cannot be in the world until I see I am in the world.” One of the sweetest moments in making this film was sharing with our crew that Disclosure was going to have its world premiere at Sundance. I think in January 2020, Park City experienced the biggest trans take-over to date, with over 30 of us from the team in attendance!

Yance Ford, the Oscar-nominated director of Strong Island, says towards the end of Disclosure, “We cannot be a better society until we see a better society. I cannot be in the world until I see I am in the world.” One of the sweetest moments in making this film was sharing with our crew that Disclosure was going to have its world premiere at Sundance. I think in January 2020, Park City experienced the biggest trans take-over to date, with over 30 of us from the team in attendance!

So, now Disclosure is in the world. Both reviews and audience feedback have exceeded our highest expectations. I’ve been spending a lot of time Zooming into Q&As. Last week a grad student asked me about my creative process. He shared that, as an Asian man who is not trans, he felt hurt that there wasn't much about trans Asian representation. And he wanted to know why. Of course, my first instinct was to defend, justify and explain the process. I wanted to tell him how limited our resources were. That one film can’t do everything. Or, what might have been the most problematic answer, “I just couldn't find it.”

While all those responses may be true, I don't think that’s what his question was about. I think because he had access to me and not the countless directors who have historically mocked his body and used his identity as a joke, his power in that moment was to ask his question. And I believe my responsibility was to interrogate my instinctual answer, to see what my answer was hiding. I wanted instead to find an answer that would validate him rather than defending myself. An answer that moves the conversation forward so I could do better next time, rather than sounding right this time.

I identified with that student because, as you may know if you saw Disclosure, I tend to point out where a film has fallen short. And in that moment between student and director, I was reminded of a film I saw about 13 years ago, a film that was surrounded by controversy for being transphobic. At a Q&A, I asked the director about her responsibility. Since she knew her film had hurt a critical mass of trans people, I wanted to know, What was her responsibility as a filmmaker?

I expected her response to be something like, “My responsibility is to give a voice to another side of things, to spark a dialogue.” But instead she said, “The artist is only responsible to herself.” To my surprise, people in the room applauded. I was gutted. I felt dismissed and scared. I was hurt that she shut the door to discussion, and didn't want to move the conversation forward. She didn't want to confront the pain she had caused.

I hope that I didn't leave that student last week feeling the way I did back then. I hope my answer, which certainly could have been better, left an opening for him, a place for him to step into, to have access, power, and to see possibilities. We are going to make mistakes. We will make choices that hurt people. I’m sure I’ve done that in this talk already. But we get to choose how we deal with those mistakes. In making Disclosure I was able to put into practice ideas and dreams I’d been cultivating—and to work on mistakes I’d been wrestling with—for the past 15 years.

I know that the way we made Disclosure, our production model—trans people on all sides of the camera, our commitment to paying everyone, and hiring and training trans people—is what makes it unique. That ethos is in every frame, and I think people feel and see it. It was not easy. But making a film is never easy. We get to choose where we put our energy, our actions, and our intention. Disclosure is proof of what can happen when the intention of the content is reflected in the process.

I’m sure many of you were at Getting Real two years ago and remember Chi-hui Yang’s inspiring talk. He led with a disclaimer that it might be too academic, but that’s what made me perk up. I love thinking about our process as filmmakers within particular frameworks. One of the things I took away from his talk was the idea of documentary power. Chi-hui explained documentary power as power relations behind the scenes, how we make our films, and how power shapes the content of our stories. If we hold documentary power accountable, we can build more equitable social, cultural, and political power on a much broader level because equitable documentary power is essential to social change.

During that talk I kept thinking about how in making Disclosure, we could put equitable documentary power into action, and how that action might radically transform our reality.

My friend, author and performer Kate Bornstein, often says, “The way we do anything is the way we do everything.” So how does equitable documentary power apply to our relationships with our protagonists?

Films are so expensive to make. We fight tooth and nail for every grant. Some of us are laughed out of rooms if our budget seems too high for our “niche” projects. That certainly happened to us! And that was when our budget was half of what it ended up being. But that laughter becomes funding if you are considered “non-niche.” I wonder, Do we replicate how the industry treats us when we make our own films? If we are lucky enough to access funding, what do we do with it? I think those choices are less about getting the film made and more about our values and intentions.

In every stage of making Disclosure, the values and intentions we held onto were the radical transformations we wanted to see for trans people both on and off the screen. So we committed to paying everyone involved, including compensating the protagonists for their time and expertise. It took years for some of our backers to understand the necessity of this commitment. Even more so, we were told that funders cannot fund a documentary that pays the “subject,” a term in itself I struggle with. Instead of saying “subject,” I use “protagonist” or “cast.” When I’ve discussed this practice of compensation with both directors and funders, I’ve been told that paying the protagonist can threaten the integrity of the film. I think the question hidden in that answer is, Whose lives do we value? When we decide on the distribution of funds we’ve raised to make a film, whose access, power, and possibility is protected or denied?

I felt 100% confident that anything our cast was going to say on camera would not be compromised by compensating them for their time and expertise. Trans and all marginalized people are so often explained and talked about by experts. But who is more of an expert of a life than the one who is living it? Trans and all marginalized people are constantly asked to volunteer their time to educate the rest of us. We as directors may not make money from our films, but we do gain cultural capital.

We explained this principle in detail in our fundraising efforts. Eventually we found the right partners to make Disclosure, and we raised the money to offer honoraria to our cast. It was hard work, but here we are. Compensating protagonists did not make or break anyone’s life conditions. But it reflected the values and messages within our film.

In making Disclosure we tried to walk the talk from top to bottom. We were committed to empowering the people on our set. We paid our cast and crew, and prioritized hiring trans people to tell a trans story. And we learned that this process could be transformative within and outside the film.

As I mentioned earlier, when we couldn't hire a trans person for a key crew role, the non-trans person hired would mentor a trans Fellow. The Fellow would learn new skills, network, and experience a set where their lives were valued and centered. Many of the Fellows are now screening their own films at film festivals across the country. One got a job at Netflix. One sold their screenplay. Another is a series regular on the HBO Max series Generation. This exchange was not unidirectional, from mentor to mentee. During breaks I’d ask our mentees if they had questions they wanted me to include in the interviews. Some of the best stories came from those questions. And there was an ineffable sense of well-being when the lights went on, the set got quiet. We’d all be a little nervous and excited as a cast member would walk on set and get into the chair for the interview. I would introduce them to the people behind the camera, who were all trans. And their faces would relax as they took in that fact.

I specifically remember the day we interviewed Lilly Wachowski (co-creator and co-director of The Matrix and Sense8). Lilly rarely does interviews; she was shy and nervous to share her stories. But when she realized that she was with people who could identify with her in a deep way, I could see her pause, and then become more at ease, almost giddy. After my interview with Rain Valdez, she said she had never had that experience before, where everywhere she looked she saw another trans person. For once she wasn't the only one.

One of our protagonists is Sandra Caldwell. She is a 69-year-old black trans woman who has worked in the industry for over 40 years, mostly not being out as trans. Our assistant director Fellow sat in awe during Sandra’s interview, realizing that one of her childhood heroes from the TV show Cheetah Girls was in fact a black trans woman, just like her.

Our chief lighting technician, Dessie Coale, a white, non-trans, queer woman who identifies as a trans ally, was so moved by her experience on set that it occurred to her that her union, IATSE, the largest tech union in the world, might not be a welcoming place for a trans person. So she took action and worked with her chapter to create a trans sensitivity training for their members, which was adopted by 49 other Locals (45,000 members).

We’re witnessing transformation for people watching the film. For trans and non-trans people alike, seeing trans people tell this history, hold it and ground it in context, contend with the violence, shame, and hate we have all internalized about trans people—seeing that outside of yourself can help you to move past it. The images that trans people have often seen in isolation are now being shared in community. Their experiences are being mirrored and validated, which can be cathartic.

Even though Disclosure did not mirror and validate the experiences of the student I spoke to last week, I hope my answers have started to. Getting there can only be done within a process in which access and power are challenged, opening the door for transformative possibilities. When that door is opened, molecules begin to shift and we start to see ourselves in the world differently.

Until we live in a world of equitable access and power, I think a framework of equitable documentary power not only includes compensation across the room, empowering people on set, but also who is in leadership. Four years ago at Getting Real, Grace Lee said this, regarding people of color: “The mandate for diverse content means there’s a lot more demand for stories about communities of color. But the practice of pairing a white veteran producer with an associate producer, editor, or other person of color to diversify your team is not the same as supporting diverse perspectives or leadership.”

Now, I don’t want to be in a world where we are regulated to tell our own stories exclusively. But while we live in a world where the most vulnerable have the least power, we must continue to center the voices which have been historically silenced. That work is done through access and power. There is a particular lens and sensitivity that a storyteller can hold only if they have a deeply personal stake in that story. And it’s through that lens and those stories that we will start to see social change.

I know this is hard work. I often wonder where we can find the time and energy and resources it demands upon us to change the rules. How do we justify the extra time it may take to raise our budgets, the days we don't take off, the self care we push aside? We all want to do our best and succeed. But if that success is relegated to yours alone, I don't think our work will ever be living up to its potential.

Getting Real has taught me so much over the years. The conversations I’ve had here allow me to think deeply about my responsibility as a filmmaker. I want to continue having conversations about how cultural equity can manifest in our filmmaking practices rather than reinforce inequity. I want to continue to develop the ways in which we make our films so they reflect the justice we want our films to convey. Even if our access and power is slight, imagine how it can grow if we share it with others.

Sam Feder’s films have screened at Sundance Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, MOMA PS-1, the British Film Institute, the Hammer Museum, and in hundreds of film festivals around the world. Feder’s work has been supported by Ford/JustFilms, Fork Films, California Humanities, The Jerome Foundation, Perspective Fund, Threshold, IFP Film Week, Good Pitch USA/Doc Society, MacDowell Colony, and Yaddo artist residency.