The IDA Documentary Awards have been a part of our programmatic mix for nearly as long as IDA’s life. Thanks to the efforts of former Board President Harrison Engle, with additional assistance from the late Gabor Kalman, the Awards launched in 1985, with five honorees for Distinguished Documentary Achievement, as well as a Career Achievement Award, which went to Pare Lorentz—whose name graces both an award for a feature or short documentary that reflects the spirit and tradition of Lorentz’s work, and a documentary fund—and a Preservation and Scholarship Award, going that year to renowned documentary historian Erik Barnouw.

The Awards program team has always been mindful of the evolution, transformation and richness of the art form and its expansion into other platforms and formats, and we have added and refined categories accordingly.

What’s more, we recognize the many stakeholders who have made such a difference in lending preeminence and power to the documentary form and ecosystem, and we have added those honors as well.

We reached out to a selection of honorees over the nearly four-decade history of the program and asked them to share their memories of what the award meant to them at that stage in their careers and what they’ve been doing since.

Nels Bangerter

Editor, Let the Fire Burn—Winner, Best Editing, 2013

Editor, Cameraperson—Winner, Best Editing, 2016

Editor, Dick Johnson Is Dead—Winner, Best Editing, 2020

I feel really lucky to have been honored by IDA, and I take the awards as a reminder that I'm part of a community that truly supports craft, and editing in particular, even when we're taking a risk on something that we don't know will work. Since finishing Dick Johnson Is Dead, I've been working on a couple of other unusual projects––looking to find a few more ways to keep audiences on their toes.

Amanda Micheli

Director, Just for the Ride—Winner, IDA/David L. Wolper Student Documentary Achievement Award, 1996

Director, with Isabel Vega, La Corona—Winner, Best Documentary Short, 2008

What follows is an excerpt from an article Documentary published in 2008.

By winning the Best Short Documentary Award for her and Isabel Vega's La Corona, Amanda Micheli became the first IDA/David L. Wolper Student Documentary Achievement Award recipient in the history of the IDA Awards to "graduate" by winning a higher-level award. The Harvard alum earned the Wolper Award in 1996 for her film Just for the Ride.

"I was up at this podium back in 1996 with my student film, Just for the Ride," Micheli said in her acceptance speech for Best Documentary Short. "And there are countless people in this room, both then and now, that have inspired and enabled my work over the last 12 years, and I'm truly grateful for this community and its support."

"Back then, I didn't even know what the IDA was," she admitted in an interview with Documentary following the 2008 Awards. "But as soon as I arrived and saw the company I was in, I was blown away, and quite honestly, I was somewhat intimidated by the pressure of expectation. As I gulped champagne, people asked with urgency, "What are you working on next??"—a question that still challenges me to this day at these kinds of events."

"I'm a serial monogamist with my films," she continued. "And like many filmmakers, I am wary of talking about new projects before they are 'in the can.' But the mere idea that people wanted to see what I was up to next was exciting, and I'd like to think that I rose to the challenge, and will continue to do so on my own timeline. Because my student film was a first-person, vérité project made with short ends and a volunteer crew over a span of many years, it was daunting to try to transform that model into a viable career. But over the years I've come to accept the insanity of it all, and have been lucky enough to have had gainful employment as a DP and producer on other filmmakers' projects while I explore my own work, which has been a real pleasure, even if it is a balancing act."

And as for the Short Documentary Award? "As I said that night, it's an honor to be recognized by such an incredible group of filmmakers, and I feel as privileged as ever to call the IDA membership my peers."

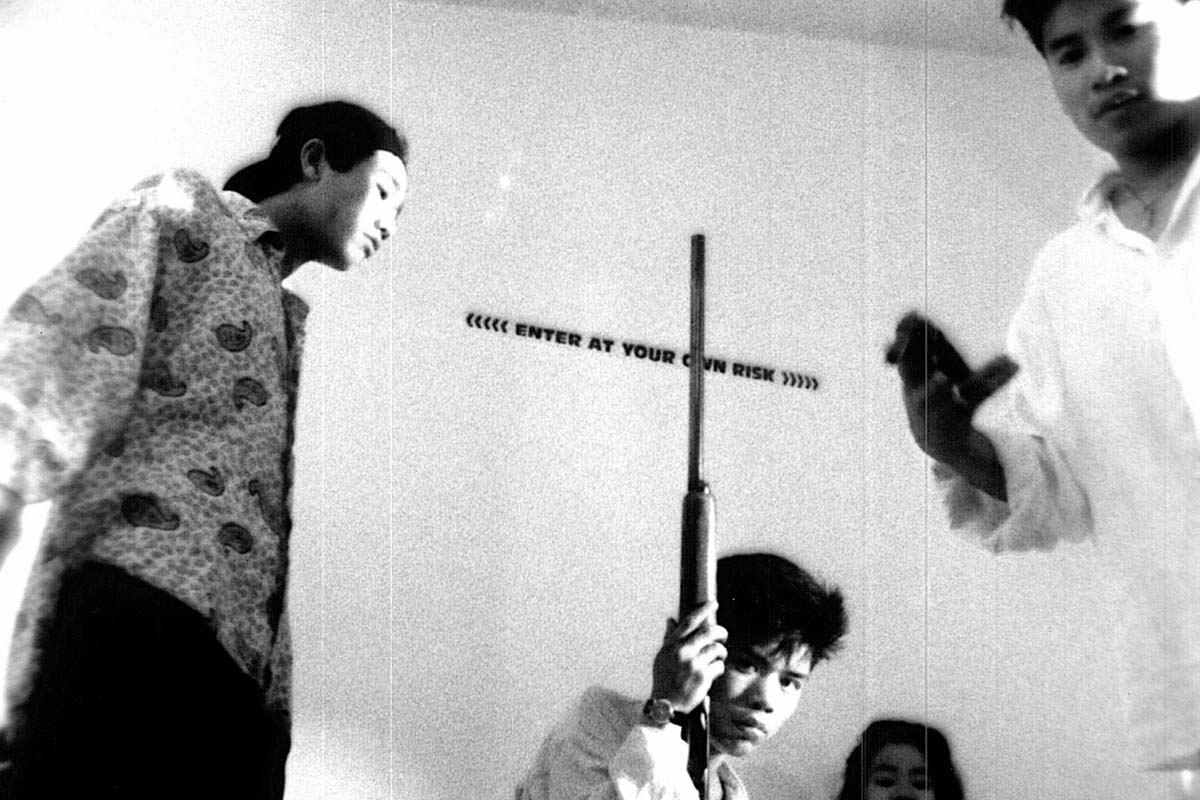

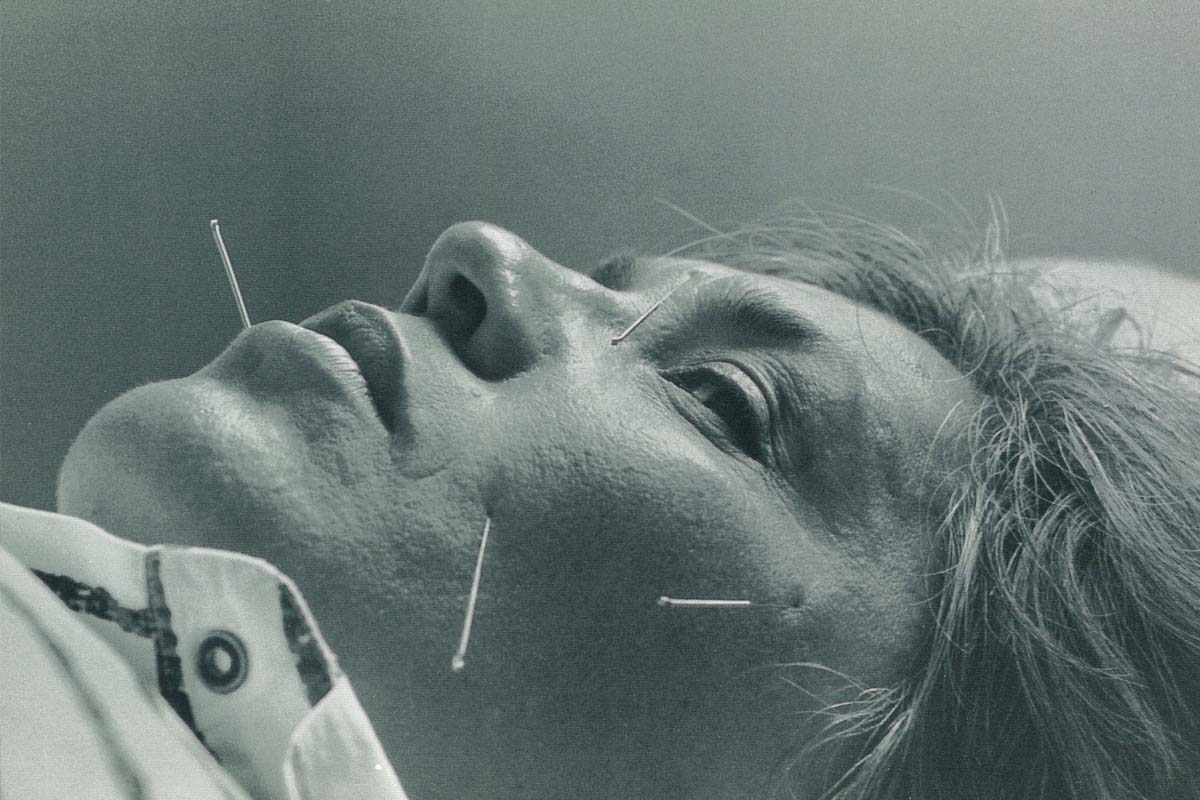

Ahrin Mishan and Nick Rothenberg

Directors, bui doi: life like dust—Winners, first Best Documentary Short Award, 1994

For a couple of young filmmakers fresh out of school, the night of the awards ceremony was like stepping into a secret society of cinematic grandmasters: Peter Bogdonavich presented us with the award; Haskell Wexler shot me a "good job” nod; and Albert Maysles, one of my idols and that evening’s Career Achievement Award-winner, encouraged me to look him up in New York. (A month later I was eating kasha in his kitchen, listening to stories about the making of Grey Gardens.)

The IDA award was, and remains, a high point in my life.

Today, I’m the executive director of a private foundation that seeks to improve the health and healthcare of marginalized populations. Everything I learned as a documentarian—most of all, listening deeply— remains essential to who I am and all that I do.

—Ahrin Mishan

After co-making bui doi, I continued toward a PhD in Anthropology at University of Southern California, having found fundraising very challenging for other film projects. I started some online side projects while at USC, during the early days of exploring the Web as a community-building and commercial enterprise. That soon became a main focus and I left my doctoral studies to help start a Web services business. Telling and selling online "stories" was distantly similar to my interests as a documentary filmmaker, and I wish I’d documented the rise and fall of the business, which certainly had a dramatic story arc. I regrouped after that, and integrated my anthropology studies and business experience to launch a small organizational development consulting firm. The last 20 years have been about helping leaders of companies, nonprofits and other organizations be as effective as possible. While the work feels a long way from documentary filmmaking, I think my background as a deep observer of people and groups has helped me tremendously in this career.

—Nick Rothenberg

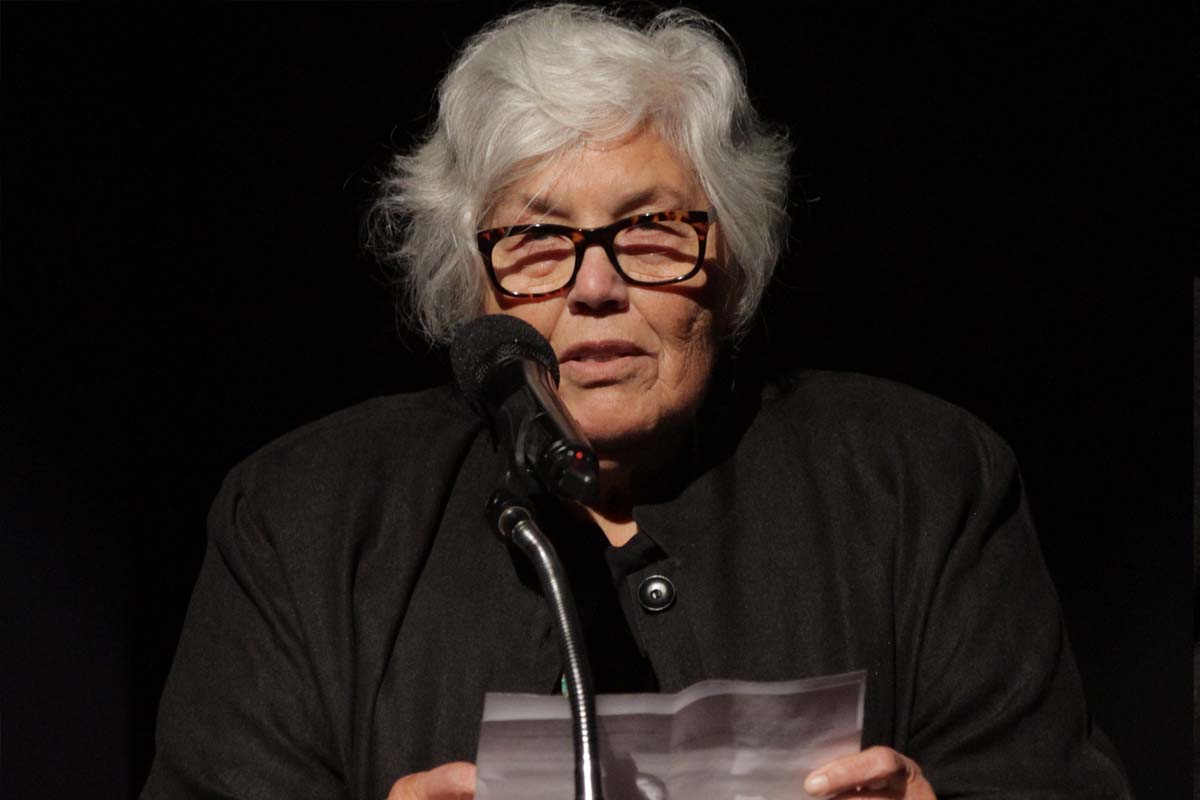

Lourdes Portillo

Director, with Susana Munoz, Las Madres: The Mothers of Plaza De Mayo—Winner, Distinguished Documentary Achievement Award, 1986

Director, The Devil Never Sleeps—Winner, Best Feature, 1995

Director, Señorita Extraviada—Winner, Best Feature, 2002

Career Achievement Award Honoree—2017

Eleven years ago, when I got sick, I was limited in what I could do. I love doing my work, and wanted to continue, but physically I couldn't do a lot. So I created a four-minute animated film called State of Grace (2020). I worked with Andrew, my nephew and an animator. I wanted to comment on what it's like to be an aging woman, dealing with illness. State of Grace has screened in the De Young Museum, at San Francisco Art Institute, at FilmFest DC, and at the Official Latino Film Festival.

For four years, I worked for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences' PST LA/LA Oral Histories project, producing the series and interviewing other Latino filmmakers about their lives and careers. In 2020, my film The Devil Never Sleeps/El Diablo Nunca Duerme (1994) was chosen by the United States Library of Congress as one of the 25 films added to the National Film Registry for that year.

I've realized over the last years how life is so fleeting. I want to leave all my papers and film materials so they can encourage other young women creators that it can be done, to inspire young women and young people to feel strong enough to continue and persevere working on their dreams in the world. So in 2021, I continue to place my film work in archives throughout the Americas to be available for students, researchers and the public, including at Stanford University's Special Collections, at the Pacific Film Archives (in Berkeley, CA), and soon to be in the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences Archives at USC in Los Angeles. Currently, I'm working on a variation of the oral histories project, and I continue to make films. A current project in pre-production is a critical look at the experimental work of artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña, a fellow artist in the Bay Area arts community.

All of my films are available through my website: https://www.lourdesportillo.com/

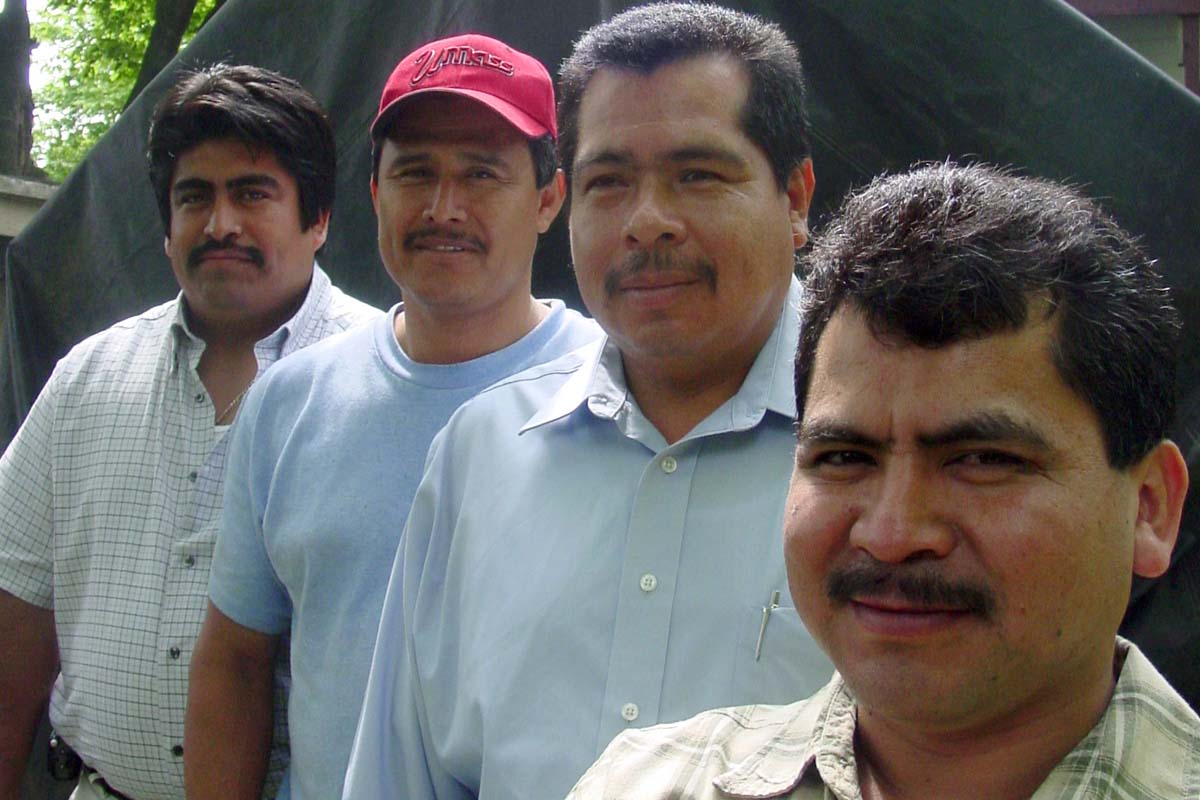

Alex Rivera

First Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award honoree (then called the Jacqueline Donnet Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award, 2003

In 2003, I was an ultra-independent filmmaker in New York City, making no-budget short films about the politics of immigration. Out of the blue, someone from "The IDA" called and invited me to Los Angeles to receive an award. I'd never heard of The IDA and I thought "documentary" was a dirty word in Hollywood. But the IDA produced a brilliant event, I made new friends who continue to be in my life today, and I returned home emboldened by that early vote of confidence. To me, the IDA has been, and always should be, an organization that takes risks, that supports divergent and deep representations of the world, and that supports filmmakers in every stage of their growth. Thank you, IDA!

Renee Tajima-Pena

Director, with Christine Choy, Who Killed Vincent Chin?—Winner, Best Feature, 1988

Tajima-Pena was also part of the directing team on The New Americans, which won a 2004 IDA Award for Best Limited Series

The recognition by the IDA Award was shocking to me, quite frankly. It was a very different IDA back in the ‘80s. As a young filmmaker of color, especially being one out in the East Coast, I felt disconnected from the organization. I had the perception that the award—and IDA—was mainly for an established, Hollywood-adjacent documentary clique that didn’t include us. At the time, both Chris and I were deeply involved in media activism with Asian American and indies of color who were fighting to get seen and heard—through organizations like Third World Newsreel and the new Center for Asian American Media (then NAATA). So the IDA Award and the recognition that Who Killed Vincent Chin? received felt very much like a collective honor, because we were all fighting together to break the barriers. In the years since, I’ve kept making documentaries, kept up that collective fight, now with new generations. And IDA has become one of our key allies in the field. Thirty-six years after the founding of CAAM, the new national A-Doc (Asian American Documentary Network) had its public launch at Getting Real ’16—something that IDA helped make happen.

Tom White is Managing Editor and Editor of Documentary magazine.