Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award: Cecilia Aldarondo A Validation of Latinx Independence

Since 2003, IDA has presented the Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award to a filmmaker whose early work exhibits extraordinary promise and expands the possibilities of nonfiction storytelling. This year, IDA recognizes Cecilia Aldarondo, a director/producer from the Puerto Rican diaspora, whose innovative films emerge from the intersection of poetics and politics. She holds an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths College and a PhD in Comparative Studies in Discourse and Society from the University of Minnesota. She is also an Assistant Professor of Art at Williams College. Through Aldarondo’s impressive career, she has been awarded fellowships through the Guggenheim Foundation, IFP Documentary Lab, New America and Women at Sundance, and is a two-time MacDowell Colony Fellow. She has been named on DOC NYC's 40 Under 40 list and on Filmmaker Magazine’s 25 New Faces of Independent Film.

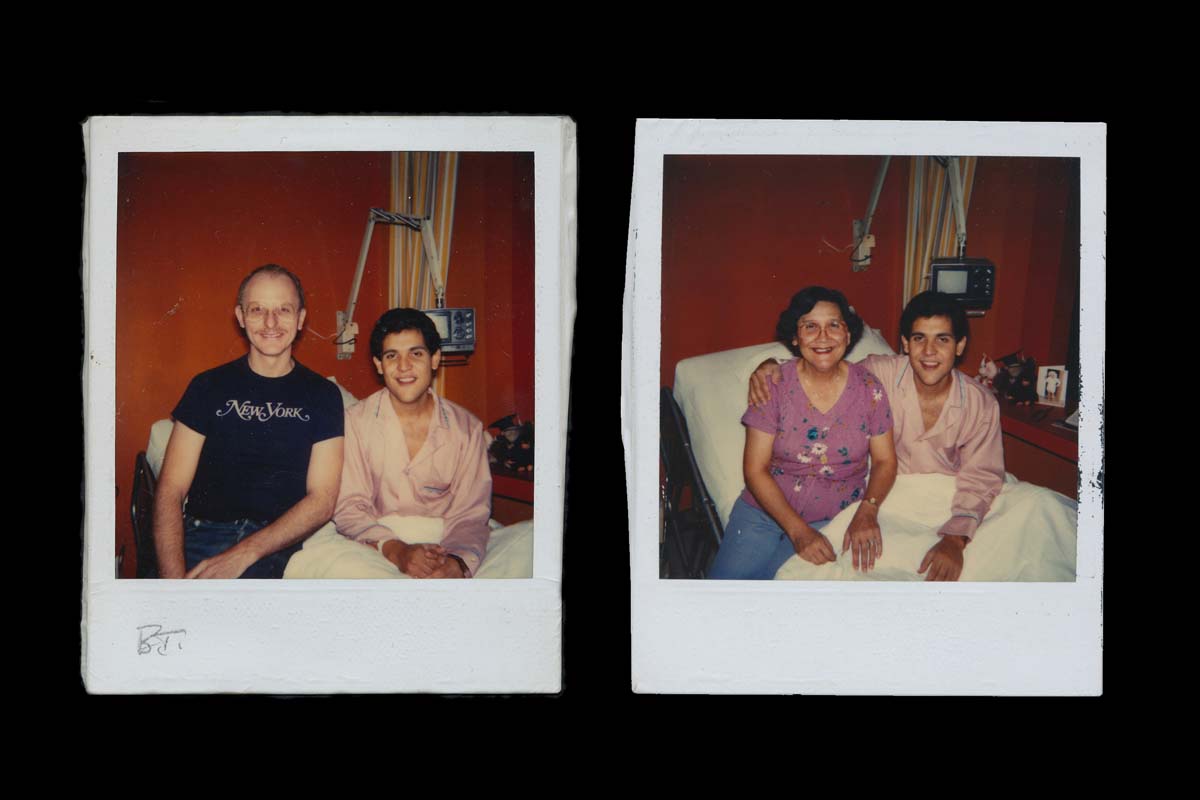

Aldarondo’s first feature documentary, Memories of a Penitent Heart (2016), delves into an intimate family secret, utilizing a creative mix of archival materials, and emotionally charged interviews and vérité footage. Her short film Picket Line (2017) follows a worker strike at a Momentive chemical plant and was commissioned for the Field of Vision/Firelight Media series Our 100 Days. Aldarondo’s most recent feature film Landfall (2020) blends two opposing perspectives of colonization on the archipelago of Puerto Rico through conversations with the community. Landfall was also the winner of the 2020 DOC NYC Film Festival Viewfinders Grand Jury Award for Best Documentary and was nominated for Cinema Eye and Independent Spirit Awards. Both of her feature films were co-produced by the award-winning PBS series POV and premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival. Currently, Aldarondo is working on her third feature film with HBO.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: What does this award mean to you?

CECILIA ALDARONDO: The news came out of the blue for me and I was really amazed that I’d been chosen. I took a look at some of the previous honorees and it seems like [they] have won at Sundance or had Oscar nominations. There’s a certain trajectory of what the industry calls success. There is a top, top tier, and my films have never quite been there. If you win at Sundance and you get nominated for an Oscar, you’re just immediately in a very different space and I think it’s important for us to note that. Who are we recognizing? What does this support mean for them? For me this award makes a huge difference in terms of the ability to live to fight another day. I really didn’t expect to get this award, especially given how challenging COVID has been for Landfall’s rollout. It felt a little bit like getting some energy back from what’s been a kind of weird time for distributing a film. I was very, very moved.

In my career, I have noticed there is a fast lane and then there is an everyone-else lane, especially during awards season. I think it’s important to note that the independent, relatively under-resourced filmmakers don’t usually break through at this level. I’m including myself as somebody who’s, up until this point, made my work through the public television system and been funded almost exclusively through grants.

D: It’s interesting that you felt like an underdog, because you have been very successful in your career.

CA: There is an increasingly stratifying set of forces in our field right now. I’ve learned from experience that if you’re trying to maintain your independence as a documentary filmmaker and not necessarily be the most commercially oriented, it can feel like there is a different set of tracks in place, particularly for filmmakers of color, unless they’re really breaking into the mainstream. My films are a little different. I’m not trying to sound ungrateful, but I feel like I’ve fought really, really hard to be able to stick to my guns and make the films that I make. It feels like a validation of that.

I know I’m extremely lucky to have gotten where I’ve gotten, but I think that we really need to be paying attention to not just the identity of the makers and the work that they’re doing but who is funding them and what the sustainability of our field looks like long term. I’m not trying to diminish the success I’ve had as a filmmaker, but it’s been incredibly hard-won and it’s been with relatively few resources compared to people with much more commercial sources of funding.

D: Do you feel you have made a significant impact in your career?

CA: It’s sometimes hard to feel the impact from where you sit, but I will say that when I started making Memories of a Penitent Heart, I remember very distinctly looking around specifically for Latinx directors that I could emulate and that I admired. This partly has to do with the kinds of documentaries that I was moved by. I could point to a number of white filmmakers whose careers I was interested in or that inspired me. I think about someone like Agnès Varda, who is a sort of queen of the French New Wave, or even people closer to home like Su Friedrich and Ross McElwee. These are filmmakers that had a very particular eye, a very independent spirit, who were making their kinds of art and films and that model of the artist/director. I couldn’t really find any Latinx directors. Maybe Natalia Almada, whose work I admired. I finished Memories in 2016. I still think we’re in a place where there are very, very few [Latinx directors].

I’m not saying that there aren’t Latinx media makers, but Latinx media makers that are really insisting upon our being able to make the films that we [want to make]. There aren’t enough of them. The whole idea of an artistic vision sometimes feels like a luxury that people of color can’t afford. If other younger filmmakers look at my work and they feel like something else is possible besides assimilating into the mainstream, I’m all for it because it can be a very lonely, lonely goal to have.

D: What inspired you to get into documentary filmmaking?

CA: I’d always been a huge cinephile. I grew up as kind of a lonely kid in Florida, really loving movies. The first job I had out of college was at the Florida Film Festival; I assisted the selection committee. At the time, all submissions were VCR-, VHS- and DVD-based. The selection committee met to screen the films, and that was kind of my film school. Then I went on to do other academic studies. I was always on the critical side: I wrote about film, studied film, did my PhD and one of my areas of study was documentary.

I had this love of nonfiction media that I was really indulging in, but I was always scared to call myself an artist or try and make something myself. I grew up in a place that didn’t really value artmaking as a viable professional pathway, and I didn’t really have any role models around me who were practicing artists. Then Memories of a Penitent Heart came along, really by accident, when my mom found a bunch of home movies in the garage and handed them over to me. I digitized the films and was looking at them with my friends. I said, What if I tried to make a film out of this? I sort of learned everything on the job by doing. I had no understanding about how the film industry worked; I didn’t know how cameras worked. I just became obsessed. It was a project that meant everything to me, so I tapped into something that gave me a tremendous sense of purpose, and I never looked back.

D: How has your work in academia supported your filmmaking?

CA: I think it’s absolutely crucial. I was just on a panel with [filmmakers] Rodrigo Reyes and Michèle Stephenson and we talked about how we as media makers have, at different times, sustained ourselves through a day job and, in my case, academia. Staying in academia [and] having that source of sustainability has given me the freedom to only focus on the films that I want to make. I think there is a lot of pressure, particularly for media makers of color, to follow a certain kind of pathway in the industry, which is to become content creators, to make branded content, to make commercials. I just never wanted to do that. I don’t fault anybody for choosing that pathway. We live in the United States. This is a hyper-capitalist society with hardly any state funding for the arts, so I get why people pursue those more commercial routes.

On a very practical level, academia gives me the ability to make my films. I basically feel like I have two full-time jobs most of the time and that requires a lot of juggling. I made Landfall while I was teaching full-time. I was basically flying to Puerto Rico on the weekends or holiday breaks to film, so it can be extremely challenging. But I feel a real symbiotic connection between teaching and artmaking. I get a lot of ideas for my films in conversation with my students. I often develop classes related to the films I’m making. I do a lot of research for my films, so I end up educating myself about the things that I’m making films about over the course of making the film. In the case of Memories of a Penitent Heart, I learned a lot about AIDS activism, AIDS art and queer media in general, so I developed a course on HIV and AIDS in film and video.

Similarly, out of Landfall I developed a course called Art in Times of Crisis. There is a really valuable interplay between my teaching and my filmmaking. I don’t think I would be an effective teacher if I wasn’t an active filmmaker. Teaching enhances my thinking on the films I make. It can be extremely difficult to have that kind of day job, but unless you’re independently wealthy, everybody has got a hustle.

D: Do you now mentor your students?

CA: Absolutely. Mentorship is really, really key, especially for filmmakers of color who may not necessarily have access to the right networks, or industry ties, or even just understand the basics of how the industry works. It’s part of why I try to be very transparent in my classes about helping them navigate the industry. I don’t just teach concepts or theory; I do a lot of practical industry-oriented work in my classes.

I have to credit a lot of the organizations that supported Memories of a Penitent Heart —for example, Firelight Media, where I met Thomas Allen Harris, my Firelight Media Documentary Lab mentor. People like Esther Robinson, who ended up becoming executive producer of the film, had made a beautiful film about her uncle. I met her through the IFP Lab. Then [at] the Sundance Edit Lab, I had this really incredible experience working with my editor Hannah Buck and the mentors that were helping us through the film—people like Robb Moss, Shannon Kennedy and Jeff Malmberg. They advised us at very pivotal times and I have learned a lot about feedback and about the importance of having people’s voices come in at the right time.

[Mentorship is] something I really try to do, whether with my students or other emerging makers in the field. Organizations, especially on the nonprofit side of our field, can make [connections] between more established makers and emerging people [that] are really important. There isn’t enough time in the day for all the mentoring I wish I could do. Something that we need to think about as a field is the labor in that mentorship. People should be paid for the work that they do and that’s something that can be sometimes undervalued as a field. So [it’s] not that I expect to be paid for every conversation I have with a student or an emerging maker, but I just wanted to note that sometimes people are asked to do a ton of mentoring and there is little time and resources to support it. I would really love for the field to be thinking about more support for mentorship on that front.

D: How does your Puerto Rican identity impact your filmmaking practice?

CA: One of the things I’ve come to understand is that as a diasporic Puerto Rican, I have a profound sense of hyphenation. What I mean by that is that migration is a huge factor in a lot of different Latinx identities, but especially in Puerto Rico which has been so shaped by migration to the United States. There is this really intense sense of dual contradiction between a profound sense of connection to home—a sense of my Puerto Rican-ness that is always there, and a sense of loss and alienation of being somebody who has, through forces greater than me, been pressured to assimilate into American culture. There is that sense of loss, whether it’s of language or history. This is a profoundly political reality and it comes from colonialism. It comes from American supremacy. It comes from capitalism. I am the product of a very mixed, hybrid sense of who I am. That means that I’m always going to look for shades of gray. It’s part of the reason I try to make films that are layered and that resonate differently for different kinds of audiences.

If we take a film like Landfall, people talk about the general audience. Will a general audience get a film like Landfall? To me, the term "general audience" is often code for a white, affluent audience. Who is in that general audience? It actually leaves out what I think to be my primary audience, which is Puerto Rican. I sought to make a film that would function along parallel intersecting tracks. The film works differently depending on your connection to Puerto Rico. Having moments that we do not translate from Spanish to English, for example, references to very uniquely Puerto Rican cultural points of cultural connection. At the same time, if you’ve never been to Puerto Rico or maybe you’ve only been there on vacation, the film will invite you in and give you space to learn.

I think my sense of a rich and complex identity makes me always seek a "both-and" way of making films, rather than an "either-or. " I don’t exclusively make my films for a Puerto Rican audience, just as I don’t try to leave our Puerto Rican viewer behind. I want to see more films that vibrate along various parallel tracks that can be layered enough so that there is space for everyone. That so-called "general audience" is actually deeply inclusive and that speaks directly to an experience. I find it profoundly problematic that the industry tends to ghettoize films by and about people like us. I believe that my films can and should be watched by everyone, and I seek to make films that are not only for people who tick the kind of boxes that I do.

D: Memories of a Penitent Heart and Landfall are both deeply personal films for you, and your presence is heavily felt or even seen in the films. How would you describe your filmmaking style and connection to the stories?

CA: I’ve always been attracted to personal filmmaking; I teach a course on it. So many of my filmmaking heroes have made personal work. I think that personal art has often been maligned and gendered as smaller, more domesticated, less important than filmmaking about the so-called bigger issues. I think that the personal is actually an incredibly important way to understand our political reality. Even a film like Landfall, which is not explicitly about my family, was still an intensely personal project because it stemmed from personal experience. The hurricane, in a very profound emotional way, impacted my family. I don’t believe in these divisions between the personal and the external or the public.

I try to make films that don’t all look the same, that don’t all function the same way. My personal belief is that the form of a film should follow whatever the idea is and whatever the primary concept is. Memories, because it was excavating our buried family history about a person, was an archival biopic.

With Landfall I felt that it had to be very much a prismatic journey because the crisis in Puerto Rico is so big, we needed a more sweeping scope. It wouldn’t have worked to just have one, two, three or four stories. But the personal weaves into all of that; intimacy and poetry are essential to who we are.

Filmmakers of color have often gravitated towards the personal register as a starting point, but I think that’s also true for anyone who’s been marginalized. This is true for Trans makers, for women, for anybody who’s left out of the official record or the official way of doing things. There is a need to excavate and understand whatever the consequences are of that marginalization.

I don’t think it’s an accident that, for example, the personal has always been a register for feminist filmmaking. I don’t exclusively see the personal as something just for filmmakers of color, but I do think that it is something that is deeply resonant for people. I continually feel like there are certain points where I’m beating my head against the industry limitations. In pitching my films and trying to get them funded, I have very frequently been told that because they’re personal, the audience is too small. But I think that that’s changing. We’re seeing more and more funders seeing [the value of personal stories]. At least on the fiction side, I’m seeing this more with projects like I May Destroy You and Fleabag. Hopefully more of this is bleeding into the documentary side. The more personal I’ve gone, the harder it’s been to get my work made.

D: What documentaries really got you interested in film?

CA: It’s such a long list, I could go on forever. It depends on what kind of inspiration I needed. Like I was saying before, part of the reason I develop courses around the films I make is that I want to share with my students the things that inspired me. If you look at my syllabus for Personal Documentary, a lot of those films influenced me while I was making Memories of a Penitent Heart.

For example, Robb Moss made this beautiful film called The Same River Twice, which is beloved but hardly seen because it’s only educationally distributed. Jay Rosenblatt’s film Phantom Limb, which is an archival film about the death of his brother. Natalia Almada’s first film, All Water Has a Perfect Memory, which is another archival film about the loss of a sibling. Su Friedrich’s film Sink or Swim, about her father. Agnès Varda’s work entirely, whether it’s The Beaches of Agnès or The Gleaners and I. She’s somebody I look to time and again.

There are just so many people who’ve motivated me as an artist. There are a lot of contemporary and even younger artists who are really breaking ground right now. I believe filmmakers of color have the capacity to radically change the form of film itself. There is a tremendous opportunity to support not just stories by and about us, but forms that emerge from necessity, from the unique contours of our experience. I also want to be inspired by filmmakers who come behind me. I want to live in a world in which filmmakers are encouraged and allowed to take great creative risks so that I can be inspired by people who haven’t made their first film yet.

Kristal Sotomayor is a bilingual Latinx freelance journalist, documentary filmmaker, and festival programmer based in Philadelphia. They serve as Programming Director for the Philadelphia Latino Film Festival and Co-Founder of ¡Presente! Media Collective. Kristal has written for ITVS, WHYY, AL DÍA, and Autostraddle. They are IDA’s Awards Competition Manager and were a 2020 Documentary Magazine Editorial Fellow.