Monumental Human Error: Observing Folly in ‘Burden of Dreams’ and ‘My Best Fiend’

Burden of Dreams. Courtesy of Argot Pictures

The eternal toil and tedium inflicted upon Sisyphus by the ancient gods needs no introduction, but what incurred their wrath in the first place? Founder of a kingdom that would later become the city of Corinth, Sisyphus was known for slaughtering his houseguests and using fear to burnish his tyrannical iron fist. While he would go on to upset the mechanics of death in the underworld, effectively sealing his ironic fate, his original sin was violating the laws of hospitality. These laws can cut both ways, especially when visitors are uninvited: in 1979, filmmaker Werner Herzog flies to the jungles of the Amazon to shoot a film about a turn-of-the-century rubber baron, Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, who strives to bring Caruso’s operas to the Peruvian city of Iquitos. As Herzog is adamant the film—Fitzcarraldo (finally released in 1982)—should not rely on special effects, the baron and the filmmaker have the same titanic task ahead of them: to transport a 320-tonne steamship over a hill and gain access to a neighboring river system.

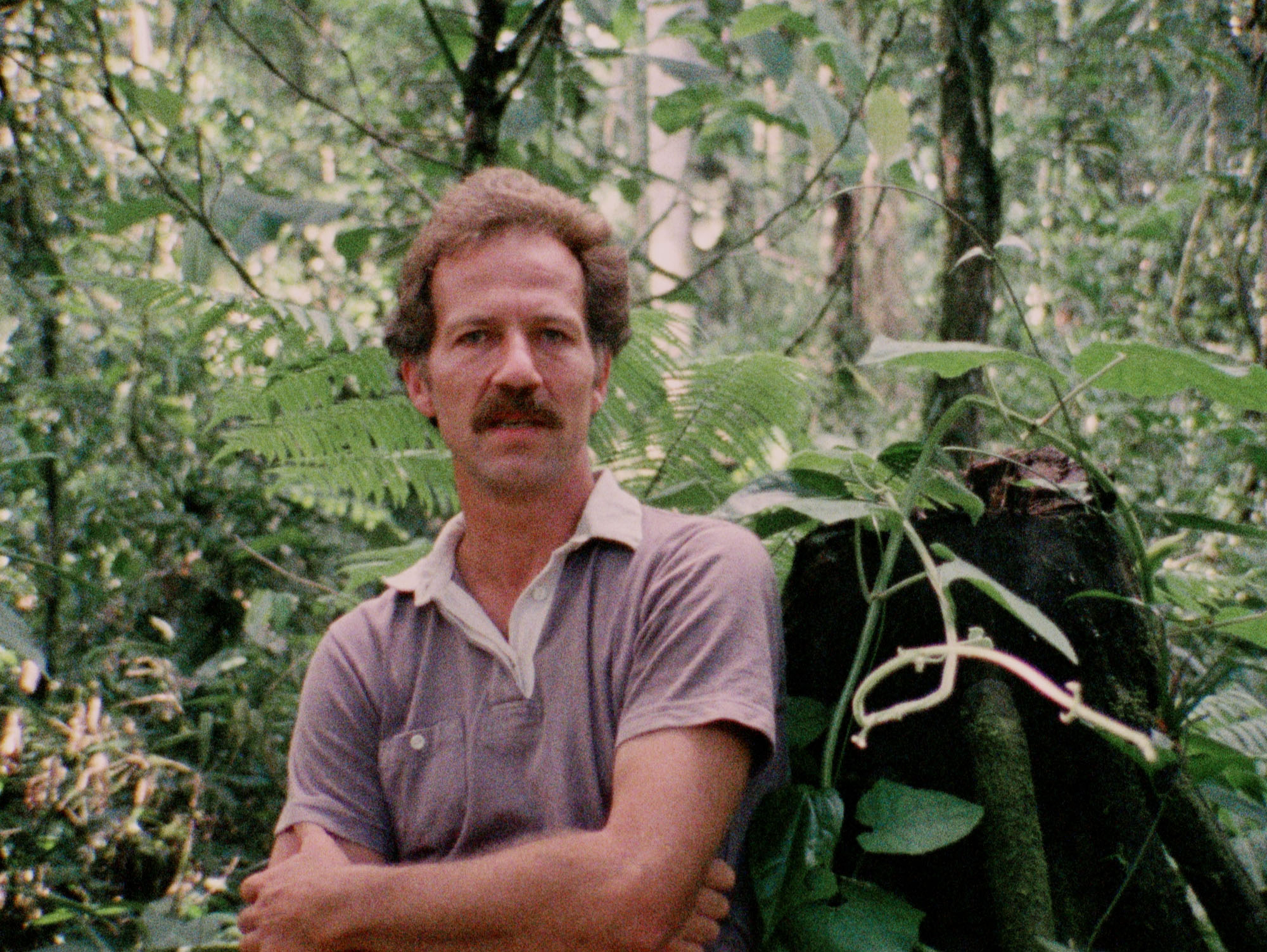

Another filmmaker, the American Les Blank, has been recruited to capture the tribulations surrounding and informing this technical feat. Blank’s 1982 documentary Burden of Dreams, newly restored by Les Blank Films and re-released by Argot Pictures, does much more than merely observe the resurrection of Sisyphus in the modern day. It also charts, and subsequently punctures, a man’s attempts to swaddle himself in the ill-fitting garments of that myth, to ennoble his self-inflicted suffering to the history books and pave over crime with punishment.

Though Burden of Dreams was made in close collaboration with Herzog and his crew, its funereal opening passages begin to dispel potential accusations of a puff piece. Herzog’s voice accompanies a shot of two Natives traveling along the river, looking back at the crew with equal parts curiosity and suspicion. The filmmaker addresses the camera, explaining what drew him to the story of Fitzgerald—dubbed “Fitzcarraldo” by the locals who could not pronounce his Irish name—in the first place. As his gaze shifts restlessly and refuses to settle into comfortable contact with the lens, Herzog describes the obstacles facing this dreamer-slash-conqueror, and in doing so, lays bare how the two men’s projects of inscribing Western art upon the Amazon are one and the same.

In this opening scene, Herzog declares, “That’s basically the story of the film,” setting into motion the two films’ cycles of Sisyphean resolve and delusion. The rest of Burden of Dreams follows along similar lines, frequently engaging closely with the shifty director, whose words are continually undercut by the surrounding footage of the Aguaruna people, their land, their customs, their precarious position within the conflicting Amazonian tribes, and their uneasy relationship to the film crew.

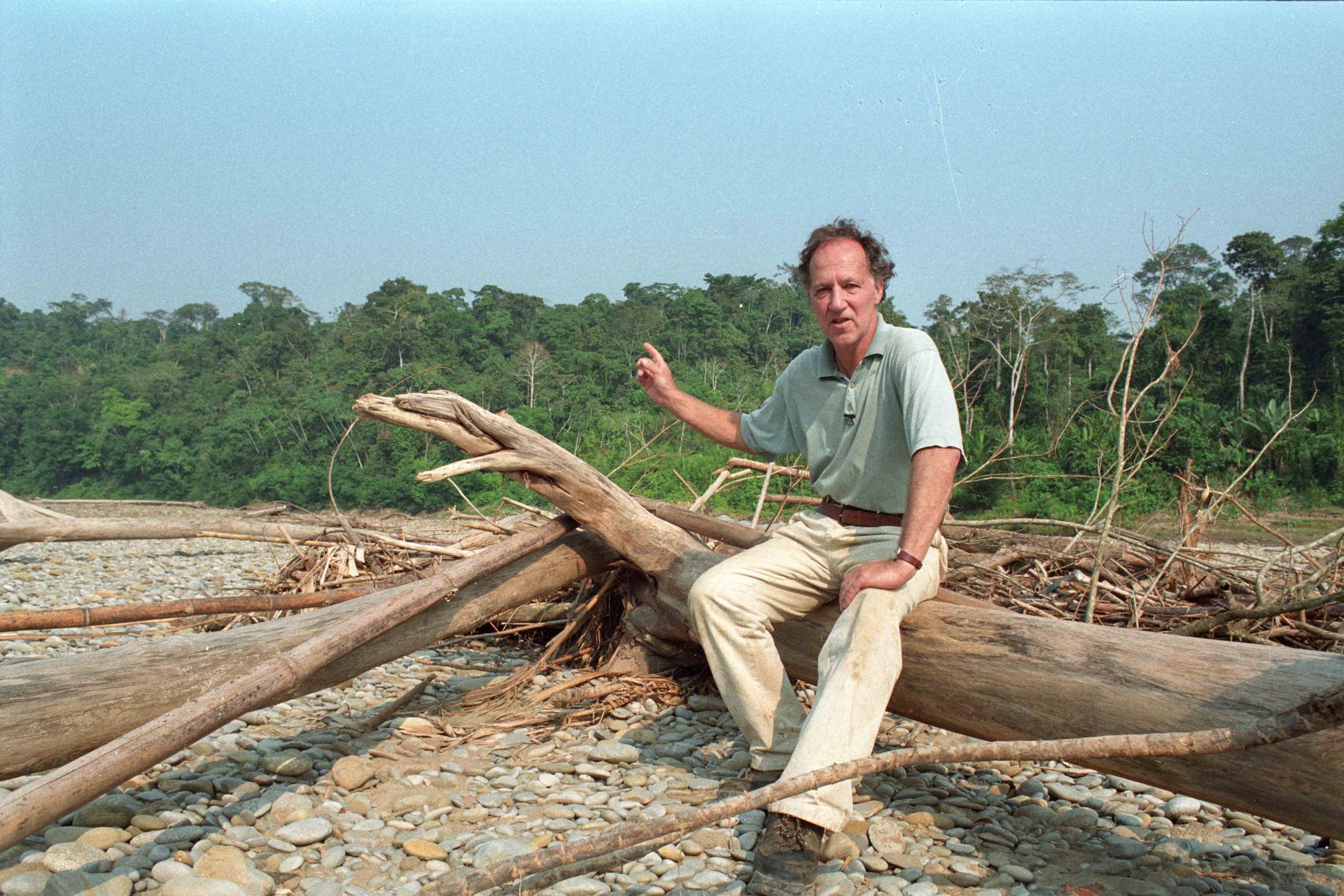

Years later, Herzog returned to the jungle to film his own documentary. My Best Fiend (1999), which turned 25 on October 7, was the director’s examination of his longstanding creative partnership with actor Klaus Kinski. Kinski agreed to play Fitzcarraldo when the original star, Jason Robards, was hospitalized midway through Fitzcarraldo’s production. My Best Fiend opens on footage of Kinski grandstanding before a large audience, shouting semi-coherently and comparing himself to Christ. The crowd cheers indiscriminately for both the rambler and his short-lived interlocutors. These archival clips—some of the only instances where Kinski, who died in 1991, is allowed to speak for himself—are both a sampling of the actor’s apparent lack of sanity and also a subtle suggestion that the man willfully leaned into his own spectacle in both art and life.

Herzog suggests this, among many other character flaws, throughout My Best Fiend, which swings vertiginously between sentimental tribute and vicious diss track. Comprising almost entirely talking heads and archival footage borrowed from Herzog’s past films (as well as Burden of Dreams), the director-star places himself in even less a position of genuine counterpoint than usual. Instead, he opts to speak directly to his camera (tellingly, his gaze is now calm and unflinching) as he moves through various sites from his and Kinski’s past.

The two documentaries each navigate a narrational tug-of-war. Where Burden of Dreams sees Blank deliberately constructing a back-and-forth between his subject and the stilted, declarative voiceover by Candace Laughlin (which functions as an extension of Blank’s authorial voice), My Best Fiend is off-balance. Even scenes where Herzog shares the screen with other subjects are slanted in his direction, their words seemingly coaxed out by a man who knows the stories by heart. When Kinski’s perspective is considered, it is only there to be contested, with Herzog reading a particularly bilious excerpt from the man’s “highly fictitious” autobiography. Immediately after claiming that Kinski’s book is built around an “obsessive compulsion” that leads inexorably back to him, Herzog admits to having collaborated on it, and even takes credit for some of the “vile expletives” assigned to him.

Where My Best Fiend’s primary form of communication is language, Herzog’s commentary in Burden of Dreams functions as annotation to Blank’s imagery, complicating and informing what we do and do not see. Unlike the former’s contradictory layers of lexical meaning, the disjunctures in Blank’s film between what we are told and what we are shown are fully intentional. Herzog’s hand-wringing over his position as an outsider throughout Burden of Dreams, his efforts to prevent the Aguaruna people from being influenced by Western culture (which resulted in segregated camps), and later, his accounts in My Best Fiend of Kinski’s constant conflicts with the Natives (who allegedly offered to kill the actor for him when tensions became unbearable) are all challenged by parallel images in the former film of the director and his star at the front of their respective boats. Herzog is shot from behind, leaning out toward the water as they speed along, while Kinski is filmed from a distance, tall and dignified, perched on the bow while the crew behind him pull the boat to shore. Herzog goes to great lengths in My Best Fiend to put distance between his and Kinski’s attitudes toward the jungle, with an emphasis on the actor’s refusal to engage with it beyond the abstract and exotic, but these distinctions only place Herzog’s savvy in a more insidious light. The rough-and-tumble explorer and the pampered conquistador; two flip sides of the same colonial fantasies.

My Best Fiend is structured to build a case against Kinski as a vain, erratic, demanding diva. Interviews with past co-stars Eva Mattes (Woyzeck, 1979) and Claudia Cardinale (Fitzcarraldo) in which they recount their favorite memories of him only pay lip service in challenging the notion that he was “impossible” to work with. The case against Kinski is far too convincing. A particularly troubling story recounts an outburst on the set of Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), the first film Kinski and Herzog shot together. The actor attacked multiple extras with a sword. “I didn’t lose consciousness, but I suffered massive bleeding,” says one of them (via Herzog’s translation) as step-printed footage depicts the assault in full. “And without your helmet, what would have happened?” Kinski’s eyes blaze as he moves toward another target. “Without the helmet, he could have killed me. He would have split my skull,” the extra continues, saying that Kinski was precise in aiming at the helmet, and that the actor’s impulsivity was always undercut with a sinister calm. The same night, however, Kinski was enraged by the crew relaxing and playing cards at camp, and fired three bullets into their hut, shooting off the fingertip of one of the 45 men who were cramped in there. Herzog stifles a chuckle as he asks further questions. “He was not quite normal,” the bewildered man concludes.

The obvious question of why and how Herzog could justify employing such a dangerous individual four more times looms over much of the film, including passages where he and the actresses reminisce about Kinski’s “great human warmth,” which could turn into rage at the drop of a hat. This particular line is followed by clips of a shouting match between Kinski and Fitzcarraldo production manager Walter Saxer, with Herzog and the crew going about their business, completely disengaged as they set up the next shot and wait for the storm to pass. The actresses’ accounts of his shyness, timidity, and sensitivity while working with them are especially troubling when considered in tandem with the experiences of Kinski’s daughter Pola, who in her 2013 autobiography revealed that he sexually abused her over a period of 15 years. In this context, Herzog’s indifference and desensitization to Kinski’s mania opens a Pandora’s box of possible indiscretions. If these are the actions that Herzog is comfortable showing, then what aren’t we seeing?

While both My Best Fiend and Burden of Dreams are rife with juxtapositions, only Blank sees fit to push his own conflicting factors toward productive counterargument—his audience is tasked with discerning a winner. Late in the film, a worn-down Herzog monologues to Blank’s camera about the futility of his mission against the elements, insisting that their project is cursed. He speaks of the obscenity and baseness of nature, and the all-encompassing misery that he sees in every creature –– “I don’t think [the birds] sing, they just screech in pain… It’s a land that God, if he exists, has created in anger.” He continues, saying, “there is some sort of a harmony—the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder.” Midway through this spiel, Blank gets sidetracked by the jungle’s flora and fauna, building a counterargument to Herzog’s fatalism in real time. As one claims that there is no real harmony in the universe, the other observes and constructs the very harmony that the film crew is actively disrupting. This “overwhelming and collective murder” relies on the presence of a Western lens that Blank attempts time and again—with varying degrees of success—to eschew. The mutilation and presentation of a parrot’s corpse by an Aguaruna, who stares defiantly into the lens, is folded back into the rhythms of life and death on the forest floor as an ant carries one of its feathers away. Where Herzog seeks to be humbled by an overwhelming lack of order, Blank seems to accept the cruelty of nature as part of a mysterious and unknowable design. Fast forward to My Best Fiend, and Herzog is only interested in nature as a backdrop.

Reflecting on the aftermath of Fitzacarraldo’s disastrous production, Herzog—in the face of countless injuries, and multiple lives lost—claims that “these are the costs you have to pay. … One starts to question the profession itself,” he continues, keenly aware of his megalomania but unable to take full responsibility for it. Given the chance to run a smooth production in the areas surrounding Iquitos, he pressed on into the volatile jungle. Warned by an expert that the steamship stunt had a 70% chance of failing, and killing upward of 60 Aguaruna people in the process, he soldiered on. What we are ultimately faced with is a man determined to view the monumental risk and folly of his production as something beyond his control; a jungle curse, a terrible duty bestowed from on high, a sentence from the gods.

Burden of Dreams and My Best Fiend both resolve on portraits of their respective subjects. The former watches a hollowed-out Herzog pose for a Peruvian photo vendor, lingering slightly on a printout of the negative. The latter concludes with extended shots of Kinski with a butterfly. He handles it with a lightness of touch one would have assumed him incapable of, but the longer we watch, the more the audience gets the sense that he is holding this creature’s life in his hands, and what stays those hands is as much a mystery as anything the man did. We also realize that he is looking at his reflection in the lens as he does so; the subject becomes a ghost, the devil becomes benevolent and merciful, and the camera becomes a mirror. Each film is confronted by an unsalvageable knot of human contradictions, and both filmmakers—whether they own up to it or not—admit defeat in the face of them.

Alexander Mooney is a critic and programmer based in Toronto. His writing has appeared in Screen Slate, MUBI Notebook, In Review Online, In the Mood magazine, and Exclaim!.