Center for Media & Social Impact Unveils State of the Documentary Field Report

(Note: Portions of this writing are excerpted directly from the full report (global findings) as well as the "15 Key Findings" report based on US respondents, co-authored with Bill Harder. Both reports and downloadable graphs are available at cmsimpact.org)

To say the documentary industry and its marketplace are changing is an understatement. In the streaming media age, we’ve never experienced so many platforms and outlets for audiences to find and view nonfiction storytelling. It’s an exciting time, from exploring genres to experimenting with new artistic ideas. In this media frenzy moment, we might be tempted to believe that filmmakers themselves—the heart and soul of the artform—face a uniformly rosy outlook. Is this true? True for some but not others? Where do documentary makers find their most vital sources of funding? What distribution mechanisms do they prefer and hope to leverage in the future? Where do they find revenue from their films, if at all? What are documentary professionals and makers experiencing as media industries evolve?

For those who care about the evolution of the documentary field and the people who create the stories, these are fundamental queries.

In this spirit, my organization, the Center for Media & Social Impact (CMSI), launched the first State of the Documentary Field research initiative—a large-scale survey of documentary professionals—in 2016, repeated in 2018 and again in 2020/2021. The State of the Documentary Field research initiative was designed to understand documentary industry members’ perspectives and lived experiences around economics, motivations, diversity and representation, funding, and changing platforms in the streaming media age. Crafted by CMSI in collaboration with IDA, the study was informed by insights and questions derived from the documentary community, along with our consultation with peer-reviewed and public-facing related research on similar topics.

This was a difficult time to examine the field. We collected survey responses between August and November 2020, notably during the first year of the historic COVID-19 pandemic, although we delayed the research from an earlier start because of the global crisis. We have released two reports, full of graphs and data points, that we hope are useful for documentary filmmakers, organizations, and other professionals who serve this community. The first report provides the story and 15 Key Findings from US-based documentary professionals and makers. The second report provides insights from the full global data, presented in two parts: all global data and US alone. Together, the full research is based on the experiences of about 900 documentary professionals all over the globe, about 600 of whom reside in the United States. (Note: We don’t find this breakdown surprising, given that CMSI and IDA are both US-based organizations, and global survey research presents many complicated challenges. But we are optimistic about expanding global participation in further waves of the study.)

Notably, in both reports, we present findings in three levels. First, we provide the big picture—that is, information about how all respondents answered each question. Next, given that our other documentary-centered research has identified differential experiences and structural challenges facing BIPOC and women-identifying documentary makers, we address those in the reports. We present each data point also as a breakdown of BIPOC/white, and gender identification (resource challenges prevent additional breakdowns for now, but we hope to pursue this in the future).

What is the big picture presented by this data, representing so many documentary professionals and makers in the US and around the world? Here are key takeaways:

-

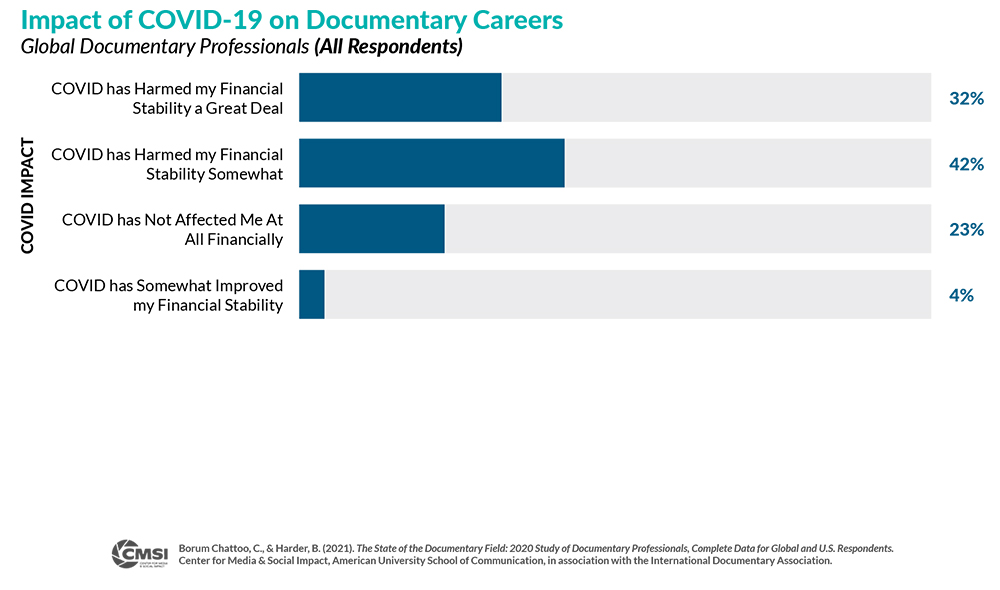

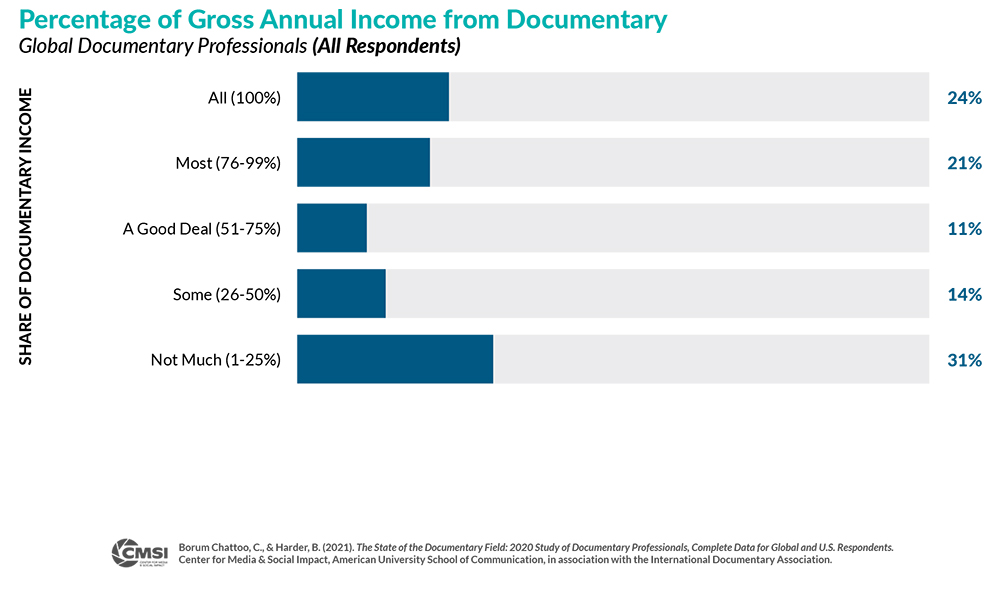

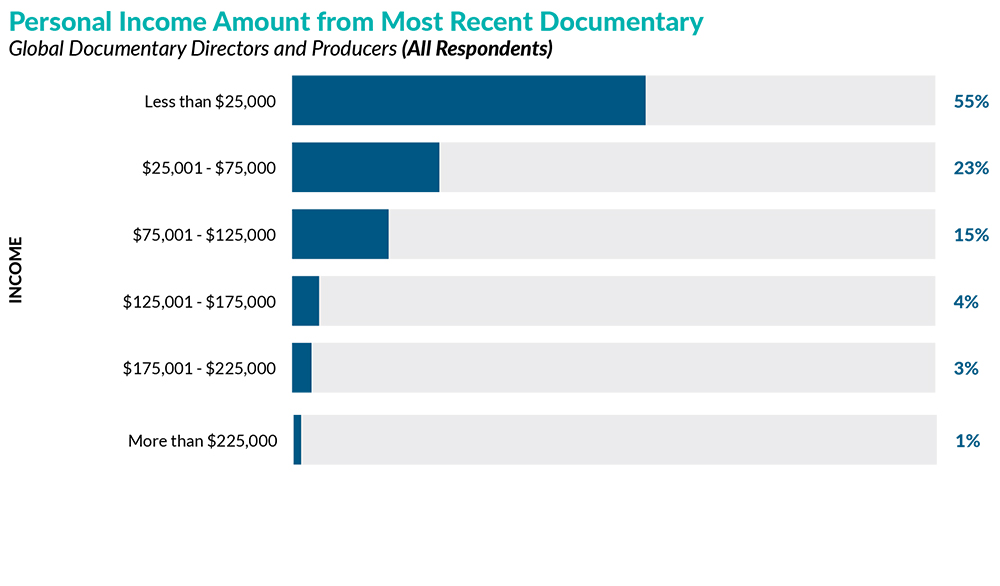

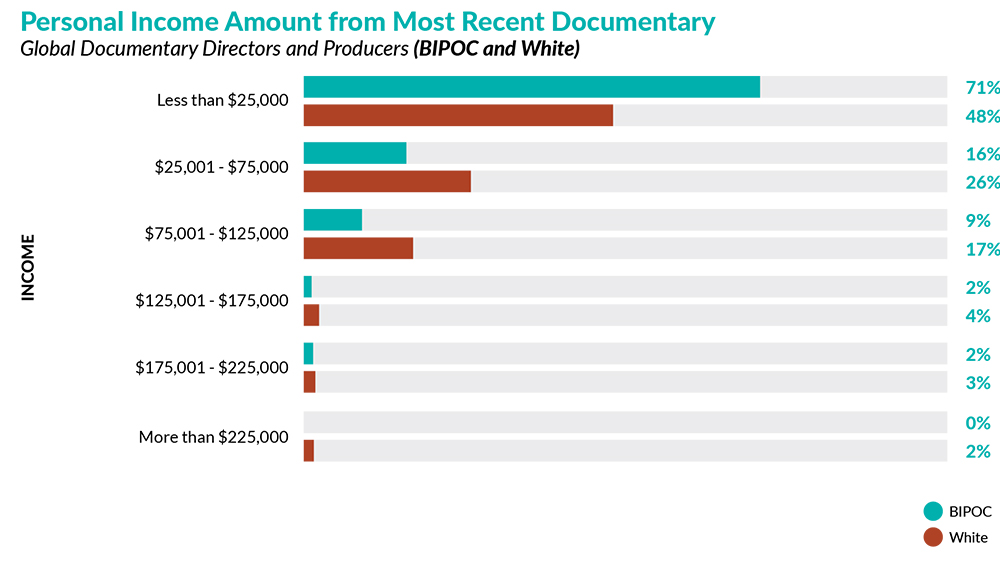

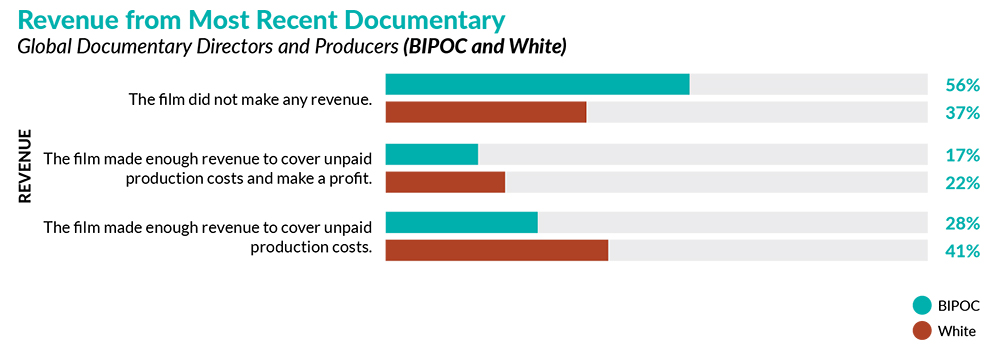

Economic issues are persistent challenges facing today’s documentary professionals. A small proportion of documentary professionals makes a full living from documentary work; the majority does other work to make a living. Less than a quarter of documentary filmmakers made enough money to cover production costs and make a profit from their most recent film; filmmakers who make a profit on their documentaries are still a rarity, not even close to the majority. Three-quarters of documentary professionals were negatively impacted financially by the COVID-19 pandemic. BIPOC and women-identifying filmmakers are the most economically disadvantaged in terms of film income, revenue, and access to bigger money that streaming networks can offer.

-

Overall, Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) documentary professionals and primary makers (directors and producers) are having a different experience in the documentary industry than their white peers. In this study, BIPOC filmmakers attest to the importance of philanthropic foundations and public TV for their funding, film-based revenue, and distribution. BIPOC makers are more likely to make short-form nonfiction stories than white storytellers, and much less likely than white makers to garner film funding, documentary revenue, and personal income from streaming networks. BIPOC makers are much less likely than white makers to have made any revenue at all from their most recent documentary film; the majority did not receive any revenue.

-

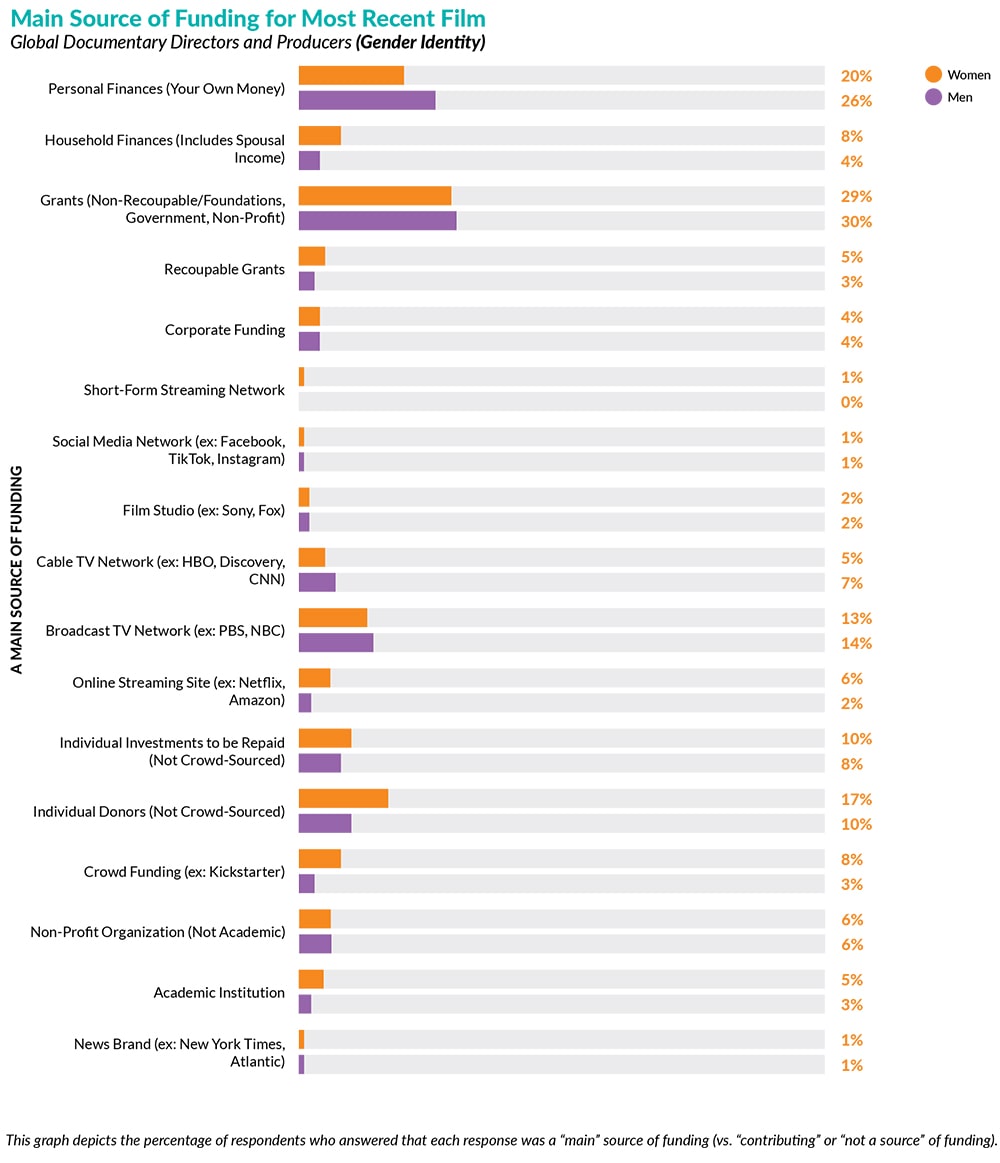

Gender identification is a meaningful differentiator in several financial categories. Women-identifying documentary professionals show some level of economic disparity in the film business. Women makers report needing to rely on sources of film funding that include household income and individual donors much more than men. Male-identifying filmmakers are more likely to be found making documentary income from streaming networks and series than women. Women makers were much less likely than men to have made any revenue at all from their most recent documentary film.

-

Documentary multi-part series are big business, and yet, many independent documentary makers still are not seeing the revenue from this work even though they see "commissioned work" from streamers and other networks as the greatest economic opportunity for the future. A small handful of players is making deals for lucrative multi-part documentary series, even though the majority of nonfiction filmmakers are interested in this work.

-

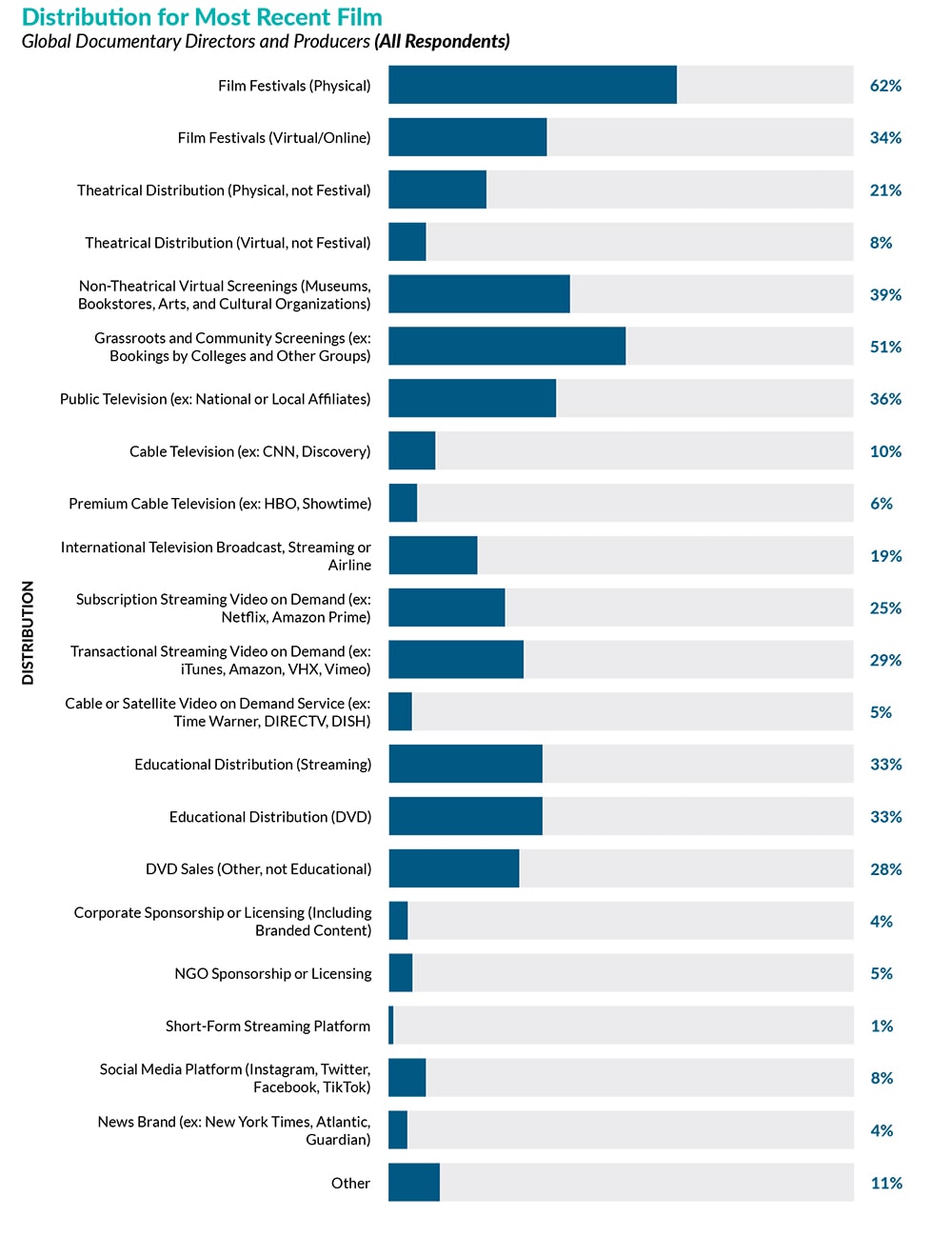

Despite the tremendous possibilities of the streaming entertainment age of media, legacy original practices and economics remain important to filmmakers. Documentaries continue to be distributed in a "dual distribution" system, with grassroots community screenings used by the majority of documentary makers to reach audiences alongside commercial and public entertainment networks. In terms of revenue sources for makers, DVD sales and educational distribution (both DVDs and streaming) matter a great deal.

-

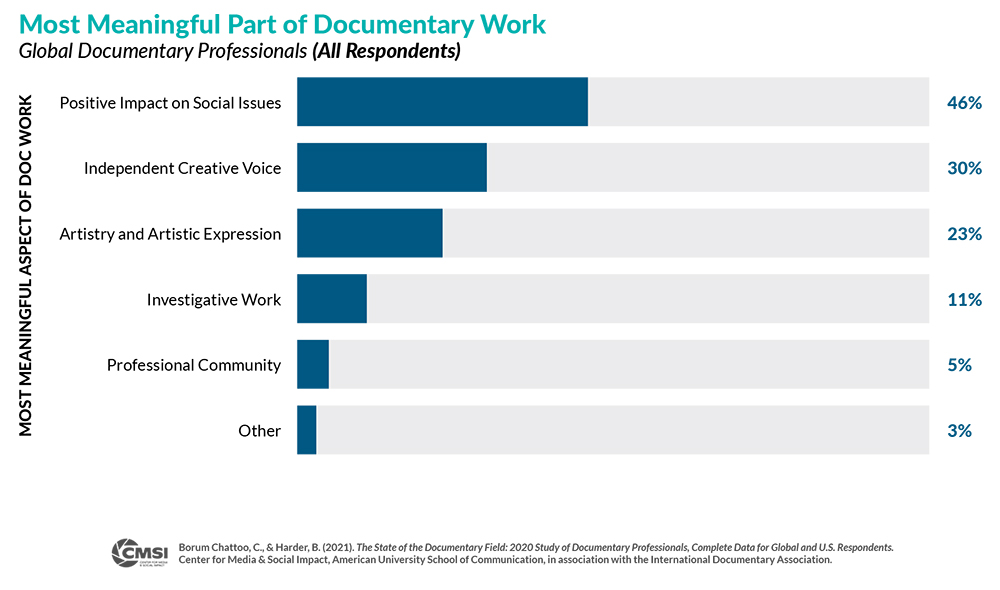

Despite the many evident economic challenges that face them, documentary storytellers are motivated by a higher purpose beyond simply making entertainment, also a legacy value in nonfiction storytelling. The majority of documentary makers are compelled to tell nonfiction stories to make a meaningful difference in urgent social issues. BIPOC and women filmmakers are the most motivated by the impulse toward positive social impact.

To read and download the 2020 State of the Documentary Field reports, access full methodological details, and access stand-alone graphs, please visit cmsimpact.org.

Caty Borum Chattoo co-directs the State of the Documentary Field research initiative, with Bill Harder. Borum Chattoo and Harder are co-authors of the 2020 report series. She is executive director of the Center for Media & Social Impact, an innovation lab and research center based at American University in Washington, DC. She is also author of the award-winning book Story Movements: How Documentaries Empower People and Inspire Social Change (Oxford University Press), which won the 2021 Broadcast Education Association Book Award.