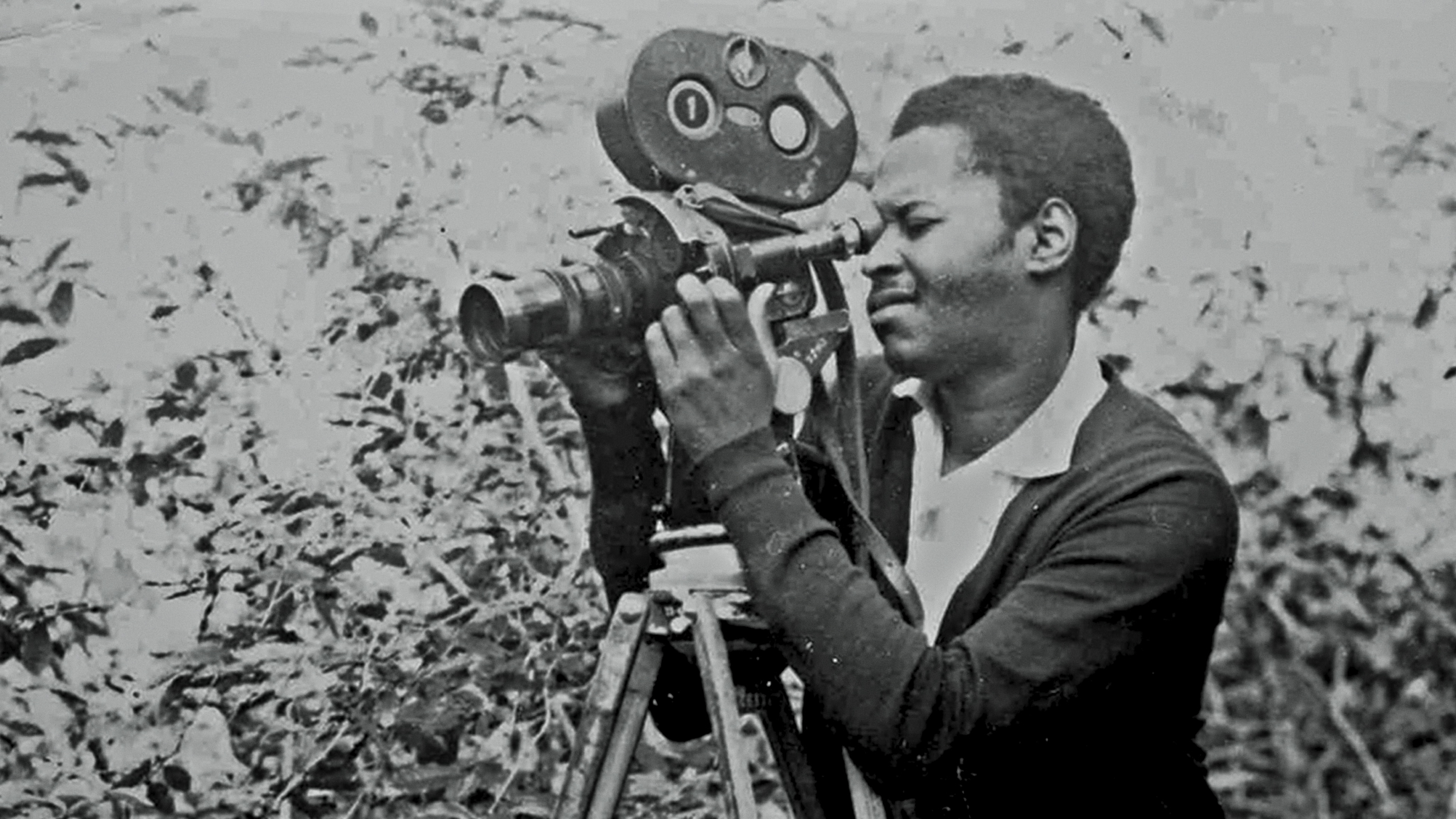

Sarah Maldoror. Courtesy of Cineteca di Bologna

Il Cinema Ritrovato’s recurring Cinemalibero strand focuses on rediscovering significant films that were “unjustly denied admission to the canon of the greats.” Often selecting films from underdeveloped countries with a history of colonial subjugation, Cinemalibero tells the story of banned, censored, and degraded films, resurrecting these works from their protracted coma through the force of new restorations. Programmed by one of the festival’s four directors, Cecilia Cenciarelli, this year’s edition included fiction and nonfiction, short and feature-length works from countries including Iran, Algeria, Syria, the Philippines, Cuba, Cape Verde, and Senegal, with a particular focus on themes surrounding the subjugation of women as well as acts of resistance from female filmmakers and characters alike.

While the strand was introduced in its current form in 2013, the origins of Cinemalibero are tied to Cinema Ritrovato’s predecessor, Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero. As festival director Gian Luca Farinelli notes, Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero, initiated in 1960 in Porretta Terme (60 kilometers outside of Bologna), was conceived by the likes of influential left-wing writer Leonida Repaci and the Italian neorealism screenwriter Cesare Zavattini as “a different kind of film festival, an alternative to Venice.” Mostra Internazionale was set up as an “anti-festival” free from political or commercial interference, committed to spotlighting films that fell, in one way or another, outside the “traditional circuits of the film and cultural industries.” Sensitive to both the radicalized mood and the egalitarian movements of the time, the festival went as far as abolishing competitions and hierarchies in 1965, further amplifying its emphasis on works dealing with the relationship between cinema and society, and showcasing films by Jonas Mekas, Glauber Rocha, Julio García Espinosa, Kenneth Anger, Věra Chytilová, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, and other titans of avant-garde and neorealist cinema. Mostra Internazionale continued until 1985, when it was moved to Bologna and started its collaboration with the Cineteca the following year—reborn as the Il Cinema Ritrovato we know today.

Two luminary filmmakers whose short films were highlighted at this year’s Cinemalibero, Sarah Maldoror and Nicolás Guillén Landrián, both emerged in the 1960s and were products of the anticolonial revolutionary movements that swept the Global South in the postwar period. Although Landrián’s work has received little exposure outside of Cuba up to this point, Maldoror has been well-known in certain circles for years, especially following the restoration and re-release of her landmark feature Sambizanga (1972) in 2020.

Three Shorts From Sarah Maldoror

As her daughter, Annouchka de Andrade (who has been working to recover her mother’s legacy), informed the audience before the screening at Bologna, it was the revered status of Sambizanga as well Maldoror’s friendship with Guinean revolutionary leaders Amílcar and Luís Cabral, that led to her invitation to Cape Verde and Guinea Bissau by the new revolutionary government to shoot the three short documentaries that were restored and showcased at the festival.

Fogo, l’île de feu (1979) begins with a close-up of feet ascending a hill before a pan reveals four men atop a barren landscape. This cues the beginning of the voice-over commentary by celebrated left-wing author François Maspero, through which we are informed this is Cape Verde—“the end of the world” as some call it, due to the excessive harshness of its landscape. This opening passage would do well as a metaphor for the then-recent history of the islands; the ascending figures captured by Maldoror evoke the liberation from Portuguese colonialism, achieved through a steep climb across a coarse landscape that lasted only as long as a mountain climber’s respite at the peak before descending the harsh terrain, as the coup of 1980 restored the rule of reaction. But for those fleeting months of liberation, the unified Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau masses stood atop a majestic peak, as did their four comrades in Fogo, and briefly glanced at the world at their feet.

These moments of unity and jubilation, of cultural and political expression, are the ones captured by Sarah Maldoror in her three documentaries between 1979 and 1980. As was the case with most of Africa at the time of colonial revolutions, Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde had severely underdeveloped rural economies, which resulted from the colonial Portuguese interest solely in extracting cheap, raw materials. Maldoror’s focus on both the economic and cultural aspects of life in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau comes precisely from this material reality and what was being done to improve it.

In Fogo, we witness people going about their daily lives, such as fishmongers attending to business at open-air markets and carriers transporting big buckets of water. Through the equally informative and poetic voice-over, we learn that while good soil suitable for farming exists, water is scarce. Perhaps this is why the camera films the water-carrying women from further away than anyone else, sneaking a peak at the precious rarity they’re transporting from a distant height. A slow, zooming shot of farmers shows them carrying hay used in constructing walls to protect coffee crops from dry winds.

While daily life goes on, so does the education of new and old generations alike. At school, the eyes of a distracted young girl, who looks everywhere except at the blackboard, suddenly meet the camera’s gaze. Outside, the education continues with an older audience through agitational speeches by a PAGIC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde) leader, comrade Pires. Throughout, Maldoror holds the shots long enough to give an impression of the proceedings but not so long as to privilege any one aspect. The film’s last part documents a friendly competition left behind by the Portuguese, centered around retrieving a suspended ring while riding a horse at full speed. As the voice-over says, the Portuguese didn’t leave anything for these people, so they took their legends and made them their own.

À bissau, le carnaval (1980) continues this theme of cultural identity, focusing on the local tradition of maskmaking. PAGIC leader Luís Cabral follows the emphasis that his late brother, Amílcar, consistently placed on culture, speaking of it as an instrument in forging a national identity for and unity between the people of Cape Verde and Guinea. It is a collective cultural activity in the truest sense: the masks are made together, and the ensuing activities are performed and enjoyed as such, with percussion music accompanying the dance of the masks that consist of a mixture of fantastical animals and human caricatures.

Cap-vert, un carnaval dans le Sahel (1979) doubles down on its explorations of local cultural practices while dispensing with informational voice-over narration and adopting a more rhythmic flow of editing. The film’s opening is not seen but heard, in the sound of waves at sea and men’s chatter over a black screen. Once our eyes are opened, the men—revealed to be fishermen, pull their boat to the shore and carry the day’s catch back to land. The waves of a somber soundtrack take us through the landscape: windmills, graves, trees, and a desert where we see a little girl, barefoot and in a white dress, strolling toward an abandoned boat. Away from the shore and desert, local youths are making a large papier-mâché octopus, which is later ornamented (with considerable effort) with a sizable papier-mâché star in the middle. As with the aforementioned films, Maldoror isn’t as interested in showing the process in immaculate detail as in giving an accurate impression of the joy of collective cultural labor. Case in point: As one local artist is carefully working on a piece, the camera zooms not on his hand or painting but on his face, as if searching for traces of the spiritual uplift brought about by the creative process.

And Four From Nicolás Guillén Landrián

Afro-Cuban filmmaker Nicolás Guillén Landrián, part of whose oeuvre has been recently restored by Cuba’s National Film Institute (ICAIC), also had four short films (En un barrio viejo [1963], Ociel del Toa [1965], Los del baile [1965], and Coffea Arábiga [1968]) at the festival. Accompanying the shorts was a new documentary about the filmmaker, simply titled Landrián. A fairly standard affair, the documentary follows his widow, Gretel Alfonso, the journey of saving the deteriorating negatives, reminiscences by collaborators, and so on. But it fulfills its mission by providing useful information about its unfortunate namesake. Landrián was viewed as an outcast of sorts by a section of the Havana bureaucracy, and after a series of disputes, he was kicked out of ICAIC. Eventually, he was admitted into a psychiatric ward due to alleged schizophrenia and was subjected to shock therapy in addition to being placed on 14 strong meds! Also a painter, Landrián eventually moved to Miami, where he put on some exhibitions and made one last film on video. He passed away in 2003.

Landrián’s life may have taken a tragic course, but his work is far from tragedy. His short films move breathlessly, like the dancers in Los del baile, Landrián’s joyous document of Havana’s nightlife. Pello El Afrokán’s music animates the bodies in front of the camera as much as the eyes gazing at the screen; even the celluloid seems ecstatic as the grains move to the rhythm of the music on its surface. The pristine, deep blacks with which cinematographer Livio Delgado captures the night become a canvas for the rhythm of shifting bodies, as well as a vessel from which the striking gaze of the documentary subjects emerges, piercing through the screen with such force as to bring the scanning eye movements of the viewers on the other side of the screen to a halt, challenging those collective eyes to a stare down across history.

Sudden cuts in the image and soundtrack ensure the viewers don’t fall into passive enchantment; like the dancers on the screen, we are kept on our feet at every moment during a Landrián film. Tableau shots captured with long lenses momentarily halt the movement of passersby from various social classes against the backdrop of Havana’s streets, while longer lenses (which Delgado utilizes with particular expertise) further accentuate the energy and movement of the already dynamic images. Despite a scattered surface, the expressions of Landrián’s films remain coherent, owing to the rebellious and free-spirited attitude flowing across them all. His work doesn’t document life in Cuba as much as it captures a certain spirit of the time. Or rather, it captures the time with a certain unmistakable, relentless spirit, best summed up by the concluding title of his films: “The End, but not really.”

Arta Barzanji is a London-based Iranian filmmaker, critic, and lecturer. He has written for MUBI Notebook, Sabzian, and photogėnie. His current film project is the documentary Unfinished: Kamran Shirdel.