By Bedatri D. Choudhury and Tom White

The COVID-inspired online edition of the 2021 Sundance Film Festival earned universal kudos, and a staggering global audience of 600,000. But with the pandemic seemingly ebbing in the final quarter of last year, the Delta variant notwithstanding, Festival Director Tabitha Jackson and her team announced that it would take a flyer on a hybrid in-person/virtual format.

Then came the Omicron variant. Up until two weeks before the festival, all eyes were cast on Park City. But, with daily case counts reaching staggering numbers around the world, the festival announced its intention to return to a virtual format—while retaining its originally scheduled 11-day span. The festival team made a quick pivot (“It’s a trigger word for the team at Sundance, now!”, Jackson joked in the opening press conference) to its virtual platform from 2021, reviving such innovations as the New Frontier Spaceship, a gateway and hub for interaction, and an opportunity for attendees to activate and unleash their avatars—their more extroverted and animated selves. “The notion of community and joy speaks to our humanity–in a world dominated by screens, gathering to experience joy is what the festival is all about,” Jackson continued. “We will converge in any way we can. This moment in the year around these artists making this work is what we’re here for—to celebrate and champion the project of freedom of creative expression and the independent voice.”

Over the festival’s run, we managed to watch a number of documentaries. Some made us cry, some made us laugh and while some made us give up hope on our times, some swooped right in to remind us to stick to our fight against forces that keep us from telling our most authentic stories. Here are some coherent bits from our post-screening conversations. We could’ve gone on talking—especially about the ways in which the films we watched approached newer, more nuanced narratives of race, maternal health and ecology—but as editors, we had to know a good time to stop.

Tom White: “Love does not consist in gazing at each other, but in looking together in the same direction.” So said Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, which could very well have served as the guiding principle for Sara Dosa’s remarkable opening night film, Fire of Love. Maurice and Kattia Kraff met as students in France in the 1960s and quickly discovered their shared passion for volcanoes—and for each other. Amid their underfinanced expeditions to lava-spewing spectacles around the world, they married—and vowed to not have children. They would devote the rest of their lives to this quirky, yet all-consuming, passion, one they would document prodigiously with an increasingly artistic and cinematic commitment to the awesome and terrifying beauty before them.

Dosa and her team created a richly textured celebration of this couple, weaving in their trove of art with an intoxicating blend of French pop music and musique concrete from their quarter-century together, and, most crucially, the elegiac narration, written by the crew and delivered with wry self-assurance by Miranda July, which rises to the occasion with its own contemplation of the mysteries of purpose, the human heart and the awesome heartbeat and blood flow of the planet. Offering a rationale for their livelihood, the couple, in one of their archived interviews, declares that they were “disappointed with humanity” and that they were more like “traveling performers” than freelance volcanologists. They delighted in dancing on the edge of the volcanoes, whether the effusive red ones or the smoldering and foreboding gray ones. To their uninitiated interviewer, they would offer up such bon mots as “Curiosity is stronger than fear” and “A fool is someone who has lost everything but reason.”

But it was their passion that would consume them both, in a fearsome rush of lava and ash. But what they left behind, and what Dosa and her team so expertly assembled, would endure as a burning testament. Editors Eric Casper and Jocelyne Chaput earned the Jonathan Oppenheim Editing Award in the US Documentary Category.

Bedatri D Choudhury: There is a surreal other-worldliness to the love story of the Kraffs; in the sense that we—the audience—identify the basic emotions of love, wonder, ego, ambition in the narrative, but the film transposes these emotions onto a geographic and visual plane that we aren’t familiar with. Joe Hunting's We Met in Virtual Reality also does that, but in a completely different way. There is that idea of a love that defies all societal barriers, but in We Met in Virtual Reality, filmed in vérité entirely within the virtual universe of VRChat, it is a love that takes off from society and finds a whole new world order.

I’ll be honest, when I went in to watch the film—and I mean I pulled my throw blanket over my feet as I lay on my couch—I thought it’d be too gimmicky. But I was quickly filled with intrigue. It starts off as a love story with couples who met in this alternate universe—we see them kissing in bars, holding hands under the night sky, and sharing an intimacy that was denied to most of us in the “real” world that was being ravaged by a pandemic. But it’s not just about the lovers. There is an ASL teacher who strives to make this parallel world more accessible and open than the world on the outside. There is a queer community that discusses possibilities and dreams that don’t find a home in our worlds. In creating this ecosystem of recognizable people, who could have well been our friends “IRL,” Hunting walks very far away from the metaverses of the Zuckerbergs and paints a picture of a world where safe spaces exist, loving communities exist and, even in the face of death and loss, human connections exist. “I essentially lived in VR during the pandemic,” Hunting said while introducing the film—which made me wish that I had this universe to disappear into when the ambulances and sirens wouldn’t stop roaring in New York City.

TW: Lucy and Desi, the debut from comedic artist Amy Poehler, spotlights another dynamic couple—Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, whose artistry and acumen would transform the television and a cultural landscape. Going into the screening, I anticipated a documentary complement to Aaron Sorkin’s Being the Ricardos. But Poehler plays the long game here, digging into the archives of Ball and Arnaz’s lives, and letting the two of them tell their respective and collective stories through a treasure trove of audio files. There’s a bootstraps aspect to both of their journeys to Hollywood and to each other: Arnaz made his way from his native Cuba, having escaped the 1933 revolution, to reconstitute himself in Miami as Cuban Pete, deploying his musical talents with Xavier Cugat, among other Latin band leaders of the era, to become a band leader and impresario in his own right. Ball journeyed from Jamestown, New York to carve out her own path as a model, a showgirl, a B-movie actor and a radio artist. The two met and fell immediately in love on the set of George Abbott’s Too Many Girls.

As they created and commandeered the sitcom of sitcoms that was I Love Lucy, Arnaz and Ball shared the load as both artistic geniuses and savvy managers, with Arnaz staving off pressure from the suits and sponsors while Ball challenged the artistic team around her to follow her lead. And though the dynamics of their business and artistic partnerships could not sustain their marriage, their venture Desilu Studios would dominate television culture for the next decade. And although they would move on to other marriages and ventures, the love they shared was always there, as daughter Lucy Arnaz explains in the film. As Arnaz was dying in the late ’80s, Ball was at his side, and in one final phone call, the two of them said “I love you.” over and over, for as long as they could.

Poehler managed to corral such artistic offspring as Eduardo Muchado, Carol Burnett and Bette Midler to testify to both the mentorship and impact of Ball and Arnaz, but what courses through the film is the dynamism and drive of a power couple to transform and dominate an otherwise hidebound world.

On the other end of the spectrum, I love what I call “film school” films—The Celluloid Closet, The Bronze Screen, Color Adjustment, Disclosure: these are essential primers in my school-of-hard-knocks education (although literature, via my BA in English, has always been my gateway drug to understanding and assessing all other artistic disciplines). So, add to the mix Brainwashed: Sex, Camera, Power, Nina Menkes’ mind-altering exegesis through 175 clips about the cinematic semiotics of gender disparity.

Drawn from her lecture Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression, which Menkes, who teaches at CalArts, has been presenting at film schools and festivals over the past few years, Brainwashed opens the space for that talk. We see Menkes interacting with her CalArts audience (shot pre-pandemic), a student focus group discussing the central points of the lecture, and Menkes again sitting in the theater, confronting one of a century-long history of male-gaze-driven clips.

As an inspiration for her exploration, Menkes cites scholar Laura Mulvey’s 1970 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” and features Mulvey as one of several talking heads, along with filmmakers Julie Dash, Amy Ziering, Penelope Spheeris, and Nancy Schreiber, and scholar Iyabo Kwayana, among others. Menkes deconstructs how shots are gendered--points of view, framing, narrative position, camera movement, lighting--and expands beyond aesthetics to argue how much cinematic harm has underscored industry and societal harm.

BC: I love that term. “Film school” films. As someone who did go to film school (probably why I yelped when I saw Laura Mulvey on screen in Menkes’ film), I really wish we had more of these. By the time I watched Brainwashed, I had already watched a few documentaries at Sundance, but how I wished I had started with this one. It’s like being taught how to see in ways that you can’t unsee.

Of course, when you talk of gender, lens and image production, you can’t help but think of Lady Diana. I have been obsessed with her and the myth around her since I was a child—I was 8, growing up in India when she passed away, and I remember the news coverage around it to be a very pivotal point in my consumption of news. I have watched all of it—Spencer, The Crown, Diana: In Her Own Words—and yet I found director Ed Perkins’ focus in The Princess intriguing. And I am not sure if it’s all Menkes’ doing, but I appreciated how Perkins uses only archival footage to prove how all of Princess Diana’s marriage was basically a PR exercise that ultimately didn’t serve the Royal Family. Her whole life, then, becomes a tool for the media to create a stomach for gossip among its readers and get them so addicted that they come clamoring for any and every bit of information that is “leaked” about her life. It strips away the feminine mystique around Diana—which I now know is a means of furthering chauvinism and misogyny—and decodes the image-making industrial complex that surrounds her life and ultimately takes over it completely.

Brainwashed also helped my viewing of Chase Joynt’s Framing Agnes in which a cast of trans actors recreate imaginary interviews of transgender people who participated in Harold Garfinkel’s gender health research at UCLA, back in the 1950s. Featuring an illustrious cast of the likes of Angelica Ross, Zackary Drucker, Silas Howard, Jen Richards, Max Wolf Valerio and Stephen Ira, this documentary aims to dismantle the the ways in which popular visual cuture has engaged, over years, in an image-making process around transgender people. The film, as glamorous as it is, also questions the inherent violence of a single gaze. Instead, what emerges is a collaborative creative vision that Joynt arrives at after exhaustive conversations with his collaborators. By doing that, he not only creates a communal history but also lays a communal claim over a history that was never made available to the community, historically. And in doing that, he counters the hegemonic, misogynist violence that, as Menkes tells us, is inherent in the cinematic gaze.

TW: I will just add that in Joynt’s previous film, No Ordinary Man, several trans men tackle the role of the late trans musician Billy Tipton, while discussing his impact on trans culture. In Framing Agnes, Joynt takes that self-reflective meta formalism further, using transcripts from interviews Garfinkel had conducted with trans people for his research as raw material for a deeper exploration of the parallels of trans culture back then with today. Alternating between this reconstruction and deeper conversations about struggles then and now, the subtext of performance and role-playing, and the consequences of disclosure, Joynt has created a multi-layered provocation that earned the NEXT Innovator Award and the NEXT Audience Award.

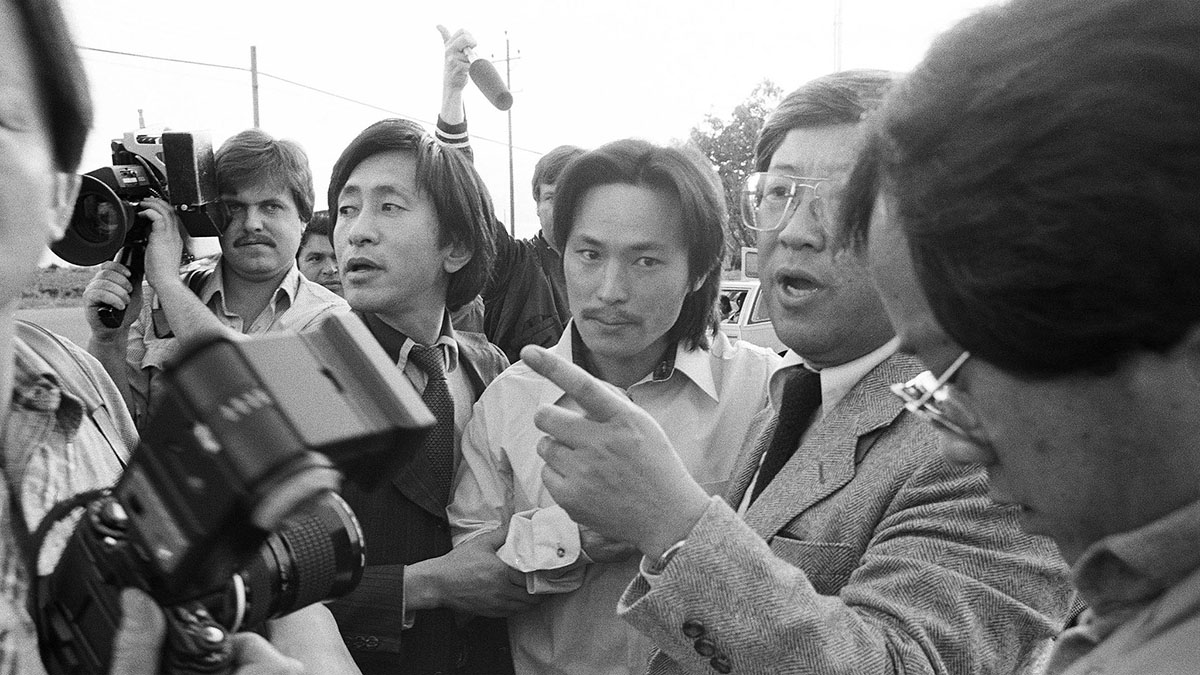

BC: Watching archival films always makes me think of archiving and what materials get sanctified within that capital “A” Archive—what is the process of selection, who selects these, and what is done with them in order to perpetuate one idea of history. The filmmakers of Free Chol Soo Lee—Eugene Yi, Julie Ha—had to go into people’s garages to find archival material about their protagonist, Chol Soo Lee, a Korean American immigrant who was wrongfully convicted of murder, in 1974. After a decade of being incarcerated, Lee was acquitted, following a massive public campaign that raised money for his appeals. Yi and Ha become archeologists digging into the past, and archivists preserving that past for the future while making this film.

Way before words like Prison Industrial Complex became an activist buzzword, Chol Soo Lee’s life was a living example of how the State’s incarceral chokehold extends way beyond prison walls and seeps into the incarcerated person’s whole world and everyone who is touched by it. The protagonist isn’t a “success story”—he didn’t magically transform his life overnight after his acquittal, and that is the crux of the story. That policing, prisons, and the larger carceral project keeps reproducing the horrors of incarceration through every point of Chol Soo Lee’s life, almost with a factory line-like efficiency and surety. Like the best documentaries, the film forces us to blur the lines that separate past, present, and future, in our heads. It reminds us of the cyclicality of power structures and how the past knows more about the future than the present ever will.

Another film that makes beautiful sense of the multilayered complexity of the present, is Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes, which won the World Documentary Cinema Grand Jury Prize. The synopsis tells us that it’s about brothers who run a makeshift bird hospital in their New Delhi basement, saving and rehabilitating birds called Black Kites. But it’s about so much more. I loved how the filmmaker’s processes of fundraising and the usual tensions of the filmmaking process find a reflection in the barriers the brothers face in the formal setting up of their hospital. Any given moment of living in Delhi now—or in most cities, for that matter—lies in the intersection of a complex matrix of religious bigotry, climate change, quality of life, human ambition, and love. Sen paces his film with such patience that it brings all of this together in a way that doesn’t overwhelm the viewer. Life-forms, as Sen’s film tells us, constantly evolve to adapt to the present, using their bodies and minds to make sense of a very complex and quickly passing time.

Kites learn to use cigarette butts as insect repellants. Human beings learn to watch the best of the world’s documentaries in their homes, amidst the regular cacophony of deadlines, cooking, cleaning, and taking out the trash. That’s how new normals evolve.

Bedatri D. Choudhury and Tom White are, respectively, Managing Editor and Editor of Documentary Magazine.