Last year, after a string of short-term contracts at a screen institute, short film festivals, and a national public broadcaster, I began a concentrated search for stable employment. Over the course of several months, I met with friends and colleagues who recounted their experiences at cultural institutions in Toronto and beyond, searching for job opportunities at organizations that provided at minimum a living wage, a work-life balance, and emotional fulfillment. Instead, I encountered stories about poor management, few opportunities for growth, long hours with low pay, and practices that were questionable at best. Certain organizations offered better benefits, working groups, or prestige, but it soon became evident that every workplace was plagued with the same baseline issues.

After one early conversation that shattered any illusions I maintained about film programming, a colleague pointed me toward World Records Journal, a semi-annual publication that offers new, complex perspectives on nonfiction media from scholars, critics, makers, and curators. Browsing through their latest volume “The Exceptions,” one particular essay drew my attention with its deceptively simple interrogative title.

In “Who Are Film Festivals For?,” film historian and curator Eli Horwatt asserts that because festivals first answer to their boards, donors, and advertisers, these film organizations, many of which are nonprofits, pursue revenue-generation and audiences over providing financial stability to the arts workers who make their events possible. The lack of will to financially compensate workers is paralleled by film festivals’ relationships to filmmakers; filmmakers pay lofty submission fees that contribute to operating budgets and, if selected, often receive remuneration in the form of lodging, airfare, and meals, but not often in screening fees or honoraria. Though a handful of festivals have taken steps towards artist fees and revenue sharing, it is generally accepted that filmmakers will be compensated through publicity and hypothetical post-festival deals.

To be sure, submission fees are necessary for administration and, more importantly, to prevent festivals from being overwhelmed by the volume of unsolicited submissions. But without transparency over acceptance rates and selection processes to make informed decisions, without fair compensation or sufficient staffing for screening committees, festivals are not only failing their workers but also filmmakers. As my conversations continued, disbelief grew into cynicism and disillusionment. Realizing that my desired career path necessitated participation in an unsustainable, exploitative system, I retreated and quietly shelved my ambitions.

Against such a fatalistic attitude, Horwatt cites advocacy efforts from filmmakers Aaron Zeghers, Nazlı Dinçel, and Scott Fitzpatrick, who always inform audiences whether they have been compensated for providing their films at post-screening Q&As. In 2021, Fitzpatrick successfully negotiated with Ann Arbor Film Festival, the oldest film festival in America, to begin paying screening fees. Last year, Anthony Kaufman reported that upon Samara Chadwick’s arrival as The Flaherty’s new executive director, she helped establish a transparent compensation scheme, employee benefits and a minimum wage of $25/hr for contractors. Conversations surrounding race, gender, disability, pay rates and job expectations are increasingly held in the public arena beside proposals for improvement, such as clearly defined job descriptions and protections for seasonal and part-time workers. Taken in good faith, these efforts suggest that film festivals, organizations and institutes are valuable spaces for exhibition, education and artist development worth reforming.

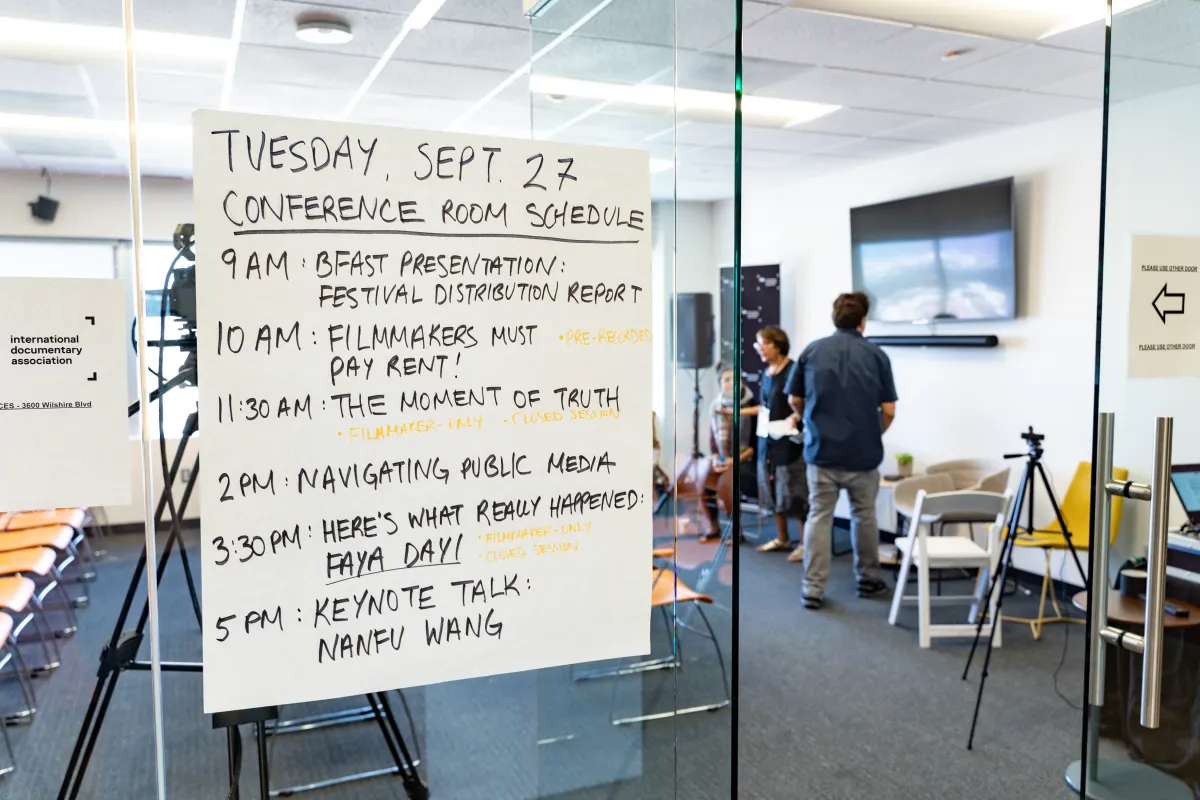

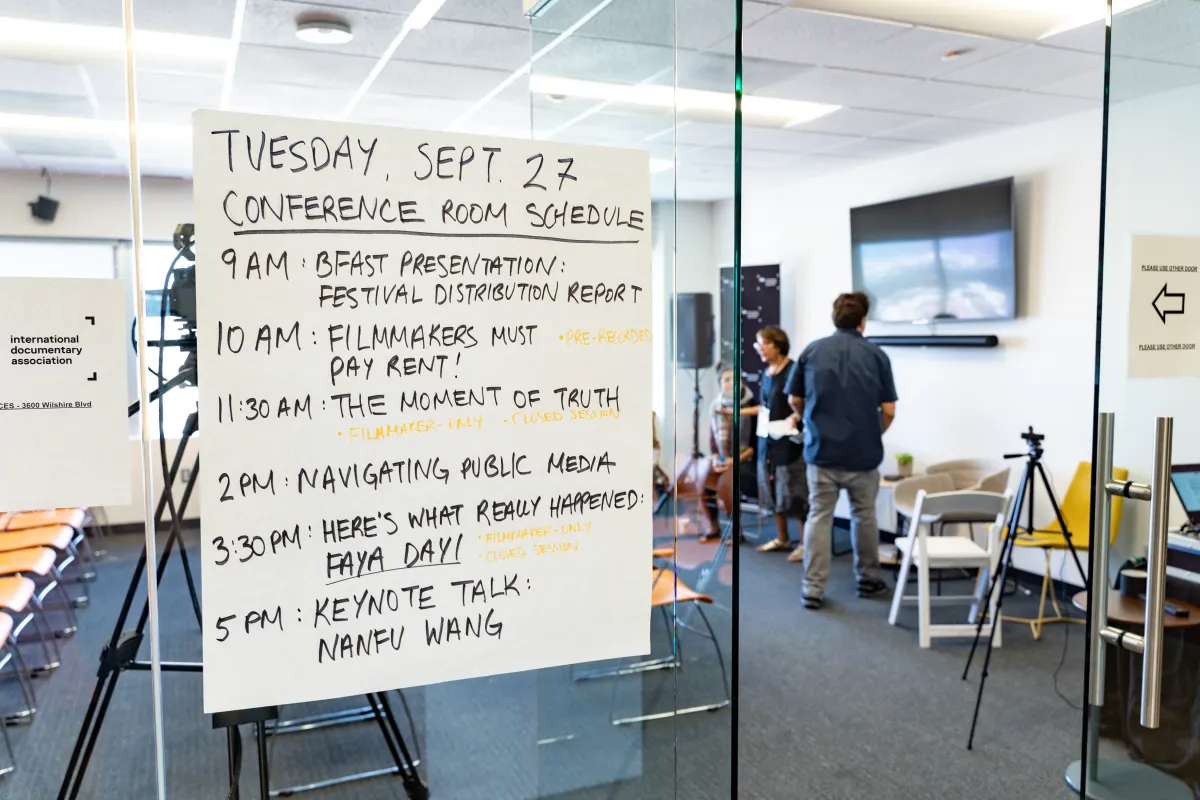

By fall, my shifting anxieties and optimism seemed to materialize at Getting Real ‘22: I was most interested in sessions that identified industry-wide concerns regarding mental health, consent, and authorship alongside new initiatives related to access materials, best practices, and accountability toward the themes of “Community, Imagination, Reverberation.”

At the “Festival Distribution Report” session, Avril Speaks and Amy Hobby of Distribution Advocates presented the preliminary results of a 2022 survey asking Sundance, Tribeca, and SXSW filmmakers about demographics, film funding, and acquisitions. Festival acceptance rates stood at 2%, 3.5%, and 4.2% respectively, with 57% of accepted films holding alumni status through a producer or director. 58 out of 70 films at Sundance sold no rights a month after the festival in North America or internationally, despite 39 of them having a sales agent. Panelists seemed unsurprised by these trends, confirming the belief that festivals cannot reliably serve as avenues for filmmakers to secure distribution. Given that festivals promote themselves as sites of discovery and acquisition, there’s a missed opportunity to extend a hand to filmmakers by publishing data that could better guide their decisions and manage expectations.

While sales agents and buyers are transacting at festival markets, workers have been tirelessly negotiating with the institutions themselves. During “Collateral Damage in Institutional Repair,” panelists Sarah-Tai Black, Jemma Desai, Cíntia Gil, Lalita Krishna, and Rachel Pronger detailed urgent, systemic instances of injustice at festivals, theaters and documentary organizations despite—or perhaps owing to—diversity initiatives and progressive mission statements. Attempts to address white supremacy, misogyny, and labor concerns within institutions were met with false narratives of progress, refusal of responsibility, and NDAs. The ubiquity of these situations draws attention to the nonprofit model as a structure that enables harm and complacency.

Krishna, a filmmaker and producer who serves as a board co-chair for two non-profit documentary organizations, explained that nonprofits often begin as well-intentioned advocacy groups but quickly become consumed with the bottom line as staff and budgets expand. However, Gil added that money and the ability to make financial decisions do not always follow power, particularly in instances when there is separation of artistic and managerial autonomy for programmers. This division of labor is why festivals are unable to answer for both their screens and workers, exhibiting films oriented towards social justice while internally refusing to recognize labor standards as human rights. When nonprofits perform the work of helping and controlling beneficiaries while subjecting workers to abuse and exploitation, the entire model must be questioned or even, as Black urged, abolished.

If we accept that the traditional nonprofit model is no longer viable, institutions might look to artist collectives for successful non-hierarchical organizational structures that center collective ownership and democracy. At “Artists Hold Power!” co-founder Nick Hayes introduced Means TV, a cooperative streaming service that distributes worker-owned, anti-capitalist media. With three categories of membership, workers are offered varying levels of commitment, dividends, and voting rights. For Hayes, the for-profit model was simply the easiest to operate under capitalism. Another example can be found in Meerkat Media, a cooperative production company built on collaboration and consensus-based filmmaking. When members or clients act against values of equity, solidarity, and care, accountability processes involving open dialogue and peer evaluation are initiated to resolve conflict and determine areas of improvement.

Certainly, the nonprofit industrial complex will not be dismantled overnight. Nor will the cooperative model alone solve issues of discrimination, harassment, and marginalization—I’d continue to be mistaken for other colleagues and have to remind people of my pronouns, consistent with my experience at every workplace. But the existence of these worker-owned and governed collectives proves that alternative models of exhibiting and producing films are within reach for festivals and other institutions genuinely seeking to reform.

By the end of the conference, attendees I encountered seemed to be invigorated. Where long standing industry standards and practices lagged far behind, filmmakers and industry workers were performing the work of engaging in institutional critique, evaluating the possibility of forging new paths, and reimagining an industry that can sustain livelihoods without sacrificing ethics, safety, and integrity. During a moment when organizations appear to be struggling with inner turmoil, staff retention, and burnout, these discussions were exceptionally timely as new industry members enter the field.

As 2023 begins, one year has passed since my search for full-time employment. With steady paychecks in one hand and long-term institutional affiliation in the other, the worst of my concerns and frustrations have eased despite working at a nonprofit. While I make sense of how to reside within the establishment, I remain faced with the typical day-to-day challenges, but now feel compelled to speak candidly beyond in an effort to build transparency and solidarity among colleagues as a minor form of resistance. Industry-wide problems that have accumulated over the past several decades have yet to be resolved. Some workplaces have worsened, forcing more staff to resign and, in turn, lowering morale. There are no easy solutions as the struggle for equity continues, but the admission that the current system is indeed broken has been revelatory, affirming the need to hold open conversations about ongoing systemic failure.

Winnie Wang is a writer, film programmer, and arts administrator based in Toronto. Their writing has appeared in Cinema Scope and Little White Lies.