Before taking my first trip to DOK Leipzig (October 27–November 2, 2025), I knew the festival primarily through its contradictions: the world’s oldest showcase for political, independent documentaries (and animated films) that operated behind the Iron Curtain for five decades; an expansive industry section that maintained a human-scale friendliness; and an unusual commitment to matching its internal practices with its public-facing programmatic focuses. As a former film festival programmer, I also admired the festival for reliably world premiering accomplished documentaries from Central Europe that escaped the notice of flashier festivals.

In the runup and on the ground, multiple filmmakers and industry workers told me that a post-1990 festival edition marked their first journey into the former GDR after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Then, the festival didn’t have a market or industry section, and the city looked completely different. Now, Leipzig slots in neatly with any contemporary mid-size European city, where the festival’s happy hours and sponsored dinners provided ample opportunities to sample the city’s cosmopolitan offerings. Everything was well run. Even the inevitable Deutsche Bahn train delays were understandable to my American eyes.

Cultural insights aside, this year’s edition, the last under outgoing director Christoph Terhechte (the well-respected former longtime head of the Berlinale Forum), demonstrated how DOK Leipzig’s historical negotiation of political constraints has evolved into a contemporary practice of institutional accountability. The festival doesn’t just screen films about labor rights, displacement, and colonial restitution, or host panels about those issues to enthusiastic crowds; it ably interrogates its own participation in these systems. When the festival programmed a special section on climate change documentaries in 2022, Sevara Pan previously reported for Documentary that it consciously declined to fly in some of the directors.

This year, that socially conscious commitment expanded through Doc Together, a new international cooperative initiative launched in March with the Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival to support displaced and exiled filmmakers, as well as those living in countries with repressive political regimes.

My trip was facilitated by an invitation from Leipzig’s Head of Industry, Nadja Tennstedt, to attend a closed-door think tank for Doc Together. I accepted with my usual skepticism and hope; so few institutions can sustain their commitments when political pressures mount, and like many other cultural events, DOK Leipzig’s budget has stagnated in recent years. According to Terhechte’s revealing mid-festival interview with Screen, although the foundational government support has remained constant at around €2.5 million, the festival has lost dedicated support for inclusion initiatives such as accessibility for film screenings.

The Doc Together think tank assembled an international brain trust to address various aspects of a festival’s obligation to support filmmakers at risk. The International Coalition for Filmmakers at Risk’s (of which IDA is a partner) coordinator, Jordi Wijnalda, delivered an opening address establishing the stakes of this discussion. Next, attendees broke out into preselected groups to discuss different topic areas, such as equitable international co-productions or mobility and visas. The festival provided a notetaker to record each conversation for a future report. In my breakout group, an exiled filmmaker, representatives from organizations that have already been working to serve artists at risk, a broadcast commissioner, and organizers from other documentary associations outlined our specific topic and proposed networked future paths for two hours. As the group’s facilitator, I think it’s on me to acknowledge that we didn’t adequately address the power dynamics of Global North institutions acting as hosts. Temporary allegiances are one thing. But in our globally connected field, can we envision more lasting relational connections that extend beyond a singular event?

The industry program also included other social commitments. The German festival workers organization ver.di’s AG Festivalarbeit (Festival Labor Workgroup) hosted a “Labour Conditions for Festival Workers” panel and launch of their 4th Fair Festival Award survey. This panel built on years of documentation about the precarious working conditions underlying festival operations, especially for an increasingly international workforce.

For attending filmmakers, other DOK Leipzig Industry programs offered many networking opportunities, educational panels, and industry updates. The Co-Pro Market arranged meetings for selected projects with a mix of international producers and broadcasters. Standouts included Ana Vijdea’s Nava Mamǎ, Zhanana Kurmasheva’s The Story of My Shirt, and Giuliano Franco Ochipinti’s That Soul Stealing Device. The showcases and pitches I attended were popular, with large audiences and the presence of many accredited industry guests. There were also two full-day conferences, one on archival producing and the other on XR.

A pitch during the DOK Preview International presentations. Image credit: Susann Bargas Gomez

Co-Pro Market meetings. Image credit: Susann Bargas Gomez

A conversation between Christoph Terhechte (L) and incoming festival director Ola Staszel (R). Image credit: Susann Bargas Gomez

Outside of the robust industry program, the festival’s history of screening independent political documentaries under state socialism provides a counterweight to contemporary discussions about documentarians necessarily ceding to political power. This year, DOK Leipzig’s special retrospective, Un-American Activities, addressed that debate head on. In the program notes, the festival explained that during its Iron Curtain era, it screened “more than 150 films from the U.S. that, due to their critical stance towards their own country,” were approved by the GDR to be representative of “another America.”

Alongside American stalwarts Gordon Quinn, Barbara Kopple, and Christine Choy, who were flown in for a panel and screenings of their work, the retrospective also offered a focused section on the films of Emile de Antonio. His legacy as a political documentarian rebutting official reports from the U.S. government has faded Stateside. A standout from this section was his In the Year of the Pig (1970), which assembles a Marxist historical counter-archive from sources all over the world, much of it never previously broadcast, and focuses its talking heads on structural analysis against the U.S. Vietnam War.

Counter-narratives weren’t isolated to the retrospective; they also pervaded the festival’s official selections, which highlighted stories that ring truer, or are more representational, than official accounts. One such film, Ivan Ramljak’s Mirotvorac (Peacemaker), won the Golden Dove top prize. It is from the storied Croatian documentary production house Factum and debuted at Factum’s ZagrebDox. Peacemaker begins with television interviews with witnesses of the 1991 assassination of Josip Reihl-Kir, the police chief of a border town between Croatia and Serbia, as he was heading to a peace negotiation. In mere minutes after Kir and three other city officials were gunned down, one interlocutor was able to insert a biased account against Kir. After this prologue, Ramljak methodically presents audio from contemporary interviewees overlaid on contemporaneous news footage, alternating between their accounts. The topics covered begin with the year leading up to Kir’s killing, anti-Serbian hatred stoked by the ultra-nationalist HDZ political party (which is back in power), and end with tributes to Kir’s last efforts to broker peace before the Croatian War. The film doesn’t arbitrate truth but documents its construction—how certain accounts gain authority while others vanish from the record.

[Peacemaker] doesn’t arbitrate truth but documents its construction—how certain accounts gain authority while others vanish from the record.

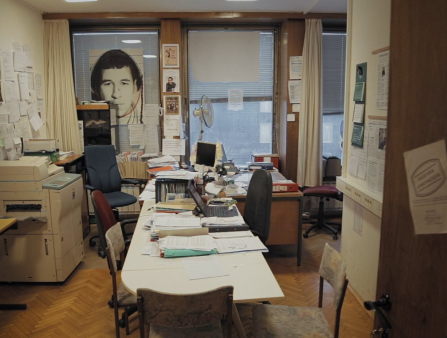

The highlight of the International Competition titles was director-cinematographer Srđan Kovačević’s The Thing to Be Done, a mostly single-location observational account of a labor rights office in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The film oscillates between three of the Workers’ Rights Office staff—a lawyer and an organizer, both named Goran, and a social worker, Laura—whose days are filled with meetings of migrant workers crowded into their small office, which has papers, posters, and slogans (“A parallel world exists”) pinned to every available surface. The staff alternately instruct, cajole, and patronize the workers who come in for their help.

Like its subject matter, The Thing to Be Done maintains a strict commitment to labor organizing praxis. Kovačević exhaustively films the minute details, allowing concrete numbers, contract details, organizing meetings, and brief snippets of interviews the staff give to journalists to play out at length while avoiding delving too deeply into the protagonists’ personal lives. There is no soundtrack, except for labor songs used sparingly in transition and in the end credits. This vérité discipline allows the film time to examine the systemic entanglements of workers’ rights and organizing politics, balancing gray areas such as the staff’s decision to operate differently than a traditional labor union in order to better serve its migrant worker members. The staff’s personalities, dedication, and warmth shine through their work. And like Kovačević’s debut feature Factory to the Workers (2022, which was filmed at the same time as The Thing to Be Done but finished first), the film’s first title card announces its production is set up as a profit-share with the protagonists. It is commitment in action, accountable to its viewers.

Another long-term, dogged effort to change systems is examined in Gregor Brändli’s debut feature Elephants & Squirrels, which won the Silver Dove for best first documentary. A multichapter structure cuts between interviews with Swiss museum directors, visits to the Wanniyala-Aetto Adivasi community in Sri Lanka, and Sri Lankan artist Deneth Piumakshi Veda Arachchige’s tireless advocacy for the return of human remains and cultural artifacts held in Swiss museums to the Wanniyala-Aetto. The objects were excavated and collected by Paul and Fritz Sarasin, second cousins and Darwinist anthropologists, and brought to Switzerland in the early 1900s. Arachchige first came across them in 2019, which is where Elephants & Squirrels begins.

The editing capably juggles every argument against museum repatriation and restitution, their rebuttals, and the increasingly in-vogue attempts to return objects against the bureaucratic red tape that disassembles progress. This is where Brändli’s behind-the-camera interviewing with the Swiss museum execs shines, as he secures on-camera admissions of changing policies and fault. In contrast, Arachchige’s documentary presence fascinatingly hovers between on-screen host and investigator. Near the end of the film, a sympathetic museum curator tells Arachchige that he’s secured funding to travel to the Wanniyala-Aetto village to visit the chief and research his claims on the remains and artifacts. When Arachchige asks where the funding is from, the curator haltingly reveals that the museum applied for a grant from the Fritz Sarasin Foundation. The pregnant pause that follows needs no explanation: exploitation funds its own reparation.

Peacemaker.

The Thing to Be Done.

Elephants & Squirrels.

DOK Leipzig also programmed plenty of personal documentaries. Of those, Sergio Oksman’s A Scary Movie seems the slightest, at first blush. A Brazilian filmmaker now living in Madrid, where he teaches documentary filmmaking at ECAM, Oksman shifted from making biographical documentaries to the personal mode with his scintillating 2012 A Story for the Modlins. In that well-traveled short, Oksman’s chance receipt of a box of photos, letters, and a VHS tape that previously belonged to an American family who became peculiar shut-ins sparks a voiceover-heavy archival rumination. His 2015 feature, O Futebol, was essentially an excuse for him to spend time with his real-life father for the first time in 20 years, in a docufiction staging set against the 2014 World Cup. Similarly, A Scary Movie, which premiered at San Sebastián, utilizes his 12-year-old son Nuno’s obsession with scary movies as the catalyst to spend a summer together in an abandoned hotel (which promised to resemble the one in The Shining, but does not) in Portugal.

Although A Scary Movie weaves in several documentary trends, it doesn’t fall victim to them. For example, through gentle voiceover, Oksman reveals that he had previously visited this Portuguese town to develop a documentary about a Spanish-born serial killer, Diogo Alves, who threw unsuspecting victims off the Águas Livres Aqueduct and became the subject of Portugal’s first fiction film, João Tavares’s Os Crimes de Diogo Alves (Crimes of Diogo Alves, 1911). This true crime crossover provides the backdrop for a series of extracurricular activities for Oksman and Nuno, but further connections to our mediatized present day are left for viewers. Editing alongside Moncho Fernández and Ana Pfaff, Oksman instead dedicates large swaths of the film simply to looking at dust motes, abandoned rooms, and hangouts between father and son.

This restraint distinguishes Oksman’s approach from the confessional saturation that currently dominates personal documentary, where every family interaction must bear the weight of universal significance. A Scary Movie achieves what more ambitious projects often miss: an acknowledgment that some mysteries resist both solution and metaphor. That we can create the realities we hope for, and that spending time together in the unfamiliar must be where we begin.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Winter 2026 issue.