Sacrificing one’s life for a higher cause is not a lone pursuit. Heroes are shaped and buoyed by supportive families who share the risks—emotionally if not always physically—alongside their loved ones. It’s a painful truth that resonates throughout Armed Only With a Camera: The Life and Death of Brent Renaud, a brutal and beautiful 37-minute tribute from Craig Renaud to his elder sibling and lifelong filmmaking partner, who was gunned down by Russian soldiers at the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The film itself embodies the verité principles the brothers championed throughout their career. Built from footage from the veteran filmmakers’ standouts, such as 2005’s 10-part Discovery series Off to War, it’s also heavily reliant on outtakes from projects like the Chicago-set 2015 Last Chance High and their reporting trips from Central America and Haiti. Due to their verité commitment, outtakes were often the only way Craig could locate moments with Brent’s voice.

Unsurprisingly, Armed Only With a Camera unfolds without narration or much explanatory text, letting Brent’s work and words speak for themselves. The HBO documentary opens with Brent’s footage from their Central America reporting, as they followed desperate young migrants crossing the river from Guatemala into Mexico, alternating seamlessly between scenes captured by Craig’s lens and Brent’s GoPro. From there it’s on to Honduras, where Brent has a probing conversation with a backpack-carrying teenager, parentless and on his own since the age of 10, who’s fleeing north with the dream of starting “a new family.” As the boy leaves to scale a barbed-wire fence, Brent calls to him, “Be careful. We hope to see you again.”

Cut to a title card reading “Seven years later.” We’re now thrust shaky cam–headlong into “Ukraine 2022,” the sounds of bombs, barking dogs, and air raid sirens portending the tragedy to come.

Young Brent holding a camera. Image credit: Renaud brothers

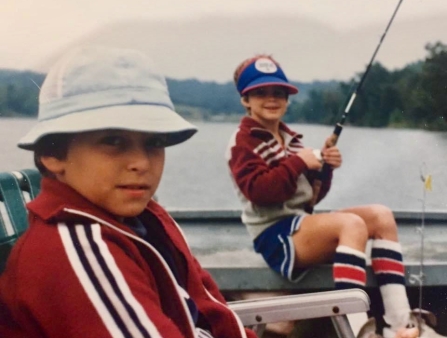

Brent and Craig fishing in 1980. Image credit: Renaud family

Brent (R) and Craig Renaud (L) editing in Iraq, 2004. Image credit: Brent Stirton

And yet, beyond such heart-pounding moments, the film is likewise a treasure trove of intimate glimpses, photos, Super 8 movies of their shared boyhood in the South, and Brent’s touching Nieman Fellowship speech, in which he speaks candidly about his autism. What becomes clear is that the Renauds’ collaboration is an intertwining of the personal and the professional, a partnership in which the two siblings became one, which makes the film’s most devastating sequence all the more heart-wrenching. Bravely, Craig has chosen to actually show Brent’s final moments through the lens of his brother’s own camera (which included speaking gently with shell-shocked civilians as they sifted through the rubble of their homes), followed by the aftermath: Brent’s body covered by a blue tarp on a Ukrainian street. Juan Arredondo, an American photojournalist, was also gravely injured during the same attack.

As Craig explained on a panel at SXSW 2025, where the film premiered, “it’s important to show what violence and war do to people. […] Why should it be any different for journalists?” He also discussed how the documentary traces Brent’s evolution from a quiet sociology graduate student to a fearless chronicler of human suffering. Their mother Georgann, a mental health professional, revealed how Brent’s autism allowed him to remain calm in war zones while finding Brooklyn dinner parties absolutely terrifying.

The spot-on title comes from DCTV co-founder Jon Alpert’s eulogy for Brent at his funeral (attended by family, friends, dogs, and documentary participants), which appears in the film along with footage of Alpert and Brent in Afghanistan for 2002’s Afghanistan: From Ground Zero to Ground Zero. Alpert, no stranger to losing beloved colleagues in the field, also served as the film’s hands-on EP—watching every cut through to final assembly, and helping Craig to “stay on message,” as the grieving sibling puts it. It was necessary to strike the right balance between the brothers’ work together as a team, and Craig’s journey to bring Brent home and continue on alone.

Even so, the documentary expands beyond personal tribute into a meditation on all conflict zone journalists and victims of war; it becomes both a mirror of the brothers’ working methodology and a final collaboration between them, one that asks whether verité work can survive in an era of increasingly dangerous and underfunded documentary work. Armed Only With a Camera airs on October 21, 2025. It’s a powerful end to the Renaud brothers’ award-winning oeuvre—recipients of Peabody, duPont-Columbia, and Edward R. Murrow awards—though thankfully for the world, both Craig and Brent’s ripple effect carries on.

***

The mission that would define both their careers began decades ago when the Little Rock–raised siblings discovered DCTV in New York, after Brent received his master’s in sociology from Columbia. They were drawn to what Alpert calls “the sort of everyday work” the center was doing within the community—a grassroots approach to storytelling that prioritized access and intimacy over production value and celebrity subjects.

“They struck me as very smart, very hardworking, and compassionate in an extraordinary way,” Alpert recalls, when Documentary caught up with him by phone after SXSW. “People could feel their compassion, which enabled them to do things others normally wouldn’t get to do.” This emotional intelligence became the brothers’ secret weapon, allowing them to gain the trust of subjects others couldn’t reach—from meth-addicted families in rural Arkansas to soldiers preparing for deployment in Iraq.

The brothers stood out among other reporters, who would “parachute in and be more concerned about themselves, their own face time, than the people who were really suffering,” Alpert notes. The Renauds’ approach was the opposite. They embedded themselves so completely in their subjects’ lives.

Craig (L) and Brent Renaud (R) at a SXSW 2017 panel for Meth Storm.

Brent (R) and Craig Renaud (L) in Iraq, 2004. Image credit: Brent Stirton

Their compassion didn’t eliminate sibling rivalry, however. Alpert recalls the two bickering about who would accompany him to the most dangerous places around the world. While preparing for Afghanistan: From Ground Zero to Ground Zero, Brent “pulled rank” on Craig with the declaration, “I’m the older brother, so I get to go.”

Under Alpert’s mentorship, the brothers learned that true verité filmmaking required more than just rolling cameras. “It’s not like, ‘add water and you’re a documentary filmmaker,’” Alpert continues. “You have to make lots of mistakes and paint yourself into corners and figure out how to get out of them.” The learning curve was steep, but the brothers proved themselves willing students, absorbing not just technical skills but the ethical framework that would guide their approach to filming people in crisis.

The turning point came with 2005’s Dope Sick Love, the Renauds’ gut-punch feature debut following drug-addicted couples on NYC streets. “That’s a really, really hard film to make,” Alpert stresses. “The main characters were full-throttle drug addicts in the throes of their addiction. Their lives were filled with their own personal challenges, and that presents challenges when you’re following them.” The film required the brothers to navigate the unpredictable world of severe addiction while maintaining their subjects’ dignity and humanity.

Initially pitched to Alpert, who declined after the emotional toll of his own Life of Crime trilogy (the first two parts were finished in 1989 and 1998), he recommended the untested brothers to HBO’s Sheila Nevins instead. It was a gamble that paid off spectacularly, launching the Renauds’ career and establishing their signature style. As Alpert observes, the film has “no music, no narration, and no cards,” which was unusual for an HBO documentary. “Sheila was forcing us to write books at the beginning of these shows! I told them, ‘Guys, nothing. Nothing except what’s in front of the camera. You’ve got to figure it out.’ And they did. I thought that was amazing.”

This vérité approach defined the brothers’ methodology throughout their career, creating both their greatest successes and their most harrowing experiences. From Off to War—which Craig calls their most challenging project “second to the film about Brent”—to their duPont-Columbia Award–winning Surviving Haiti’s Earthquake: Children (2011) for the New York Times, the brothers consistently chose the most dangerous stories to tell.

Off to War exemplifies their immersive style and showcases the advantages of their Arkansas roots. The project was a nonstop two-year commitment: a full year embedded with the Arkansas National Guard in Iraq, six months of pre-deployment training, and six months documenting soldiers’ reintegration into civilian life. The hometown connection proved crucial for access. Despite the troops having Army-issued talking points for media encounters, “they would turn around and come up to us and talk like we were close friends,” Craig recalls, laughing at the memory.

The series captured not just the obvious drama of combat, but the quieter moments that revealed character: soldiers calling home, struggling with equipment, forming bonds that would sustain them through trauma. It was the kind of long-form storytelling that required the subjects to forget the cameras were there; a trust the brothers earned through their consistent presence and genuine concern for the soldiers’ welfare.

Craig Renaud filming Dope Sick Love. Image credit: Josh Miller

Craig Renaud filming on the Guatemala border. Image credit: Renaud brothers

Brent Renaud filming in Cité Soleil, Haiti. Image credit: Renaud brothers

Haiti proved even more emotionally and physically demanding. The brothers had been in the country covering upcoming elections for the New York Times when the earthquake struck. They were in the Times office putting final touches on a documentary about the country’s “turning a corner,” when the paper’s Dave Rummel, who was then the senior producer of news and documentary, asked them to return immediately for a vastly different story. This juxtaposition—from hope to catastrophe—would become emblematic of their career.

Craig found himself crossing the Dominican border into Haiti within 24 hours of the earthquake, before any Western help had arrived. “There were bodies piled in the streets, and people with open wounds and amputations walking around, having no idea where to go,” he says, his voice still carrying the shock of that initial encounter. Meanwhile, Brent embedded with the Navy hospital ship Comfort, documenting the medical response from a different angle. The brothers’ ability to coordinate coverage while working separately demonstrated their mature partnership and shared editorial vision.

While other journalists focused on death tolls and political implications, the Renauds zeroed in on individual survival stories, specifically on two injured Haitian children who had remarkably lived through the disaster. These young survivors became flesh-and-blood embodiments of the nation’s resilience, their personal struggles illuminating larger truths about human endurance. “We always tried to find stories that took you much deeper,” Craig explains, a philosophy that required an emotional investment that took its toll on the filmmakers.

The Haiti assignment also revealed how the brothers’ compassionate approach sometimes led them into ethically complex territory. When Craig’s fixer asked if they might search for his family first, the line between journalism and humanitarian aid blurred. These moments—captured in their footage but rarely discussed publicly—demonstrated the impossible choices facing conflict journalists who care deeply about their subjects.

***

True immersive journalism requires serious time commitment, dramatically increasing both physical risk and financial cost—luxuries few independent filmmakers can afford in an era of shrinking budgets and shortened attention spans.

The brothers’ methodology raises urgent questions about the future of conflict zone vérité journalism in America. Their approach required resources and commitment that seem increasingly impossible in today’s media landscape. Were any other American directors following in their “immersive narrative nonfiction” footsteps, as Craig has always categorized their work?

“I don’t know of anyone who’s done it as consistently and for as long as we were up until the point Brent was killed," Craig admits, though he noted Sebastian Junger (Restrepo) had taken a similar approach to conflict journalism.

The scarcity of practitioners reflects the method’s demands. True immersive journalism requires serious time commitment, dramatically increasing both physical risk and financial cost—luxuries few independent filmmakers can afford in an era of shrinking budgets and shortened attention spans. “It only cost us a plane ticket and our time,” Craig stresses, but that simplicity belies the enormous personal investment required.

What set the Renauds apart was their complete self-sufficiency. “The ability to do everything ourselves” made their approach financially viable, Craig explains. From initial development and field production to postproduction and final edit, the siblings functioned as a two-person crew that never needed to hire additional staff. While this type of small production still exists, it’s become a far less common way of working in commercial documentaries slated for broadcast and cable. Though born of necessity, this efficiency became their competitive advantage, allowing them to stay in the field longer than crews dependent on larger budgets.

“Brent always said the edit is what makes the difference,” Craig highlights as another crucial aspect of their process. While many directors still choose to shoot their own footage, few also handle the complex work of story assembly. The brothers understood that their raw material—often hundreds of hours of footage from months or years in the field—only gained meaning through careful editorial choices. “We don’t follow a schedule, we follow the story,” was another Brent mantra, according to Arredondo, emphasizing their commitment to organic narrative development.

Their mentor’s influence remained constant throughout their evolution. With Alpert as their guide, the goal was to be “as pure verité filmmakers as we could possibly be.” This uncompromising technique extended all the way to 2017’s Meth Storm, their final major collaboration, in which the brothers maintained their immersive approach while adapting to new realities. The project found them deeply embedded with two sides of the drug crisis in rural Arkansas—from intergenerational users and dealers to the local DEA agents who knew them all by name. But this time the story was in their “backyard,” allowing Craig to go home at night, given his growing responsibility to his young family and a recognition that the physical and emotional toll of their work had accumulated over two decades.

***

Craig and Arredondo plan to continue as filmmaking partners, but Craig has no immediate plans to return to conflict zones. But “never say never,” he allows, acknowledging that his trip to Ukraine to retrieve Brent’s body was a nightmare no one could have predicted. The hedged response reflects both the unpredictable nature of global events and the magnetic pull that conflict journalism exerts on those who understand its importance.

Arredondo himself embodies the continued commitment to this dangerous work. After undergoing 13 operations in the span of a year following the attack that killed Brent, he jumped at the chance to take on a New York Times assignment in his home country of Colombia, taking his colostomy bag along without telling the Times. His determination validates Alpert’s observation that “once you see the horror of war, it gets inside you like nothing else can. And you’re determined at any cost to help people understand the horrors of war.”

March 13, 2025, marked the third anniversary of Brent’s death, but for Craig, who created Armed Only With a Camera both as loving tribute and psychological survival mechanism, it has felt like one continuous three-year-long day. The film serves multiple functions: memorial, manifesto, and maybe most importantly, a master class in the verité approach that fewer and fewer filmmakers are willing or able to practice. In an era of remote interviews, archival storytelling, and docutainment, their commitment to physical presence and emotional investment seems almost quaint. Craig’s decision to show the ultimate cost of their chosen profession ensures that Armed Only With a Camera functions as both celebration and warning. The pool of practitioners willing to risk everything for the story grows smaller with each passing year.

Brent Renaud filming in Ukraine, 2022. Image credit: Juan Arredondo

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Fall 2025 issue.