Kirsten Johnson has been a cinematographer and director since the 1980s. Her acclaimed films as a director include The Above (short, 2015) , Cameraperson (2016) , and Dick Johnson Is Dead (2020), all of which grapple with the meaning behind making images, their utility in conveying reality, and the strength of documentary images as visual evidence. For this interview, Documentary asked longtime archival producer and producer Stephanie Jenkins ( Muhammad Ali , 2021) to catch up with Johnson via Zoom. As a co-founder of the newly formed Archival Producers Alliance, whose other organizers are

Over the years, Jemma Desai’s writing, programming, research, and practice have intersected with institutional critique. Through investigating film institutions’ languages of colonialism, she’s brought renewed attention to hierarchies, systems, words, and ways of relating that are often taken for granted. Born out of a combination of rigorous research, firsthand experience working in institutions such as the British Council and the BFI, as well as testimonies by other arts workers, This Work Isn’t for Us (first self-published in 2020) was a crucially timely study of the fundamental problems

An interview with two organizers of the Archival Producers Alliance on how AI will shake up the nature of archival footage For the first decades of this century there was, relatively speaking, intermittent media coverage of Artificial Intelligence or how deep learning and related technologies were creeping into aspects of work, culture, and society. But then in late 2022, OpenAI released the large language model ChatGPT to the public—and stories about AI exploded. Subsequently, the coverage around AI in the last year or so has reached a point of fatigue, even satire: “It’s AI” has become a

"It's about time there was an organization just for us. An organization whose sole purpose is ‘to encourage and to honor the documentary arts and sciences; to promote nonfiction film and video; to support the efforts of nonfiction film and video makers all over the world." Excerpt from the invitation letter sent out by Linda Buzell to the documentary community in 1982. 42 years ago, on February 6, 1982, in Los Angeles, 75 members of the documentary field convened for the first meeting of what would become the International Documentary Association. The meeting stemmed from a grassroots appeal

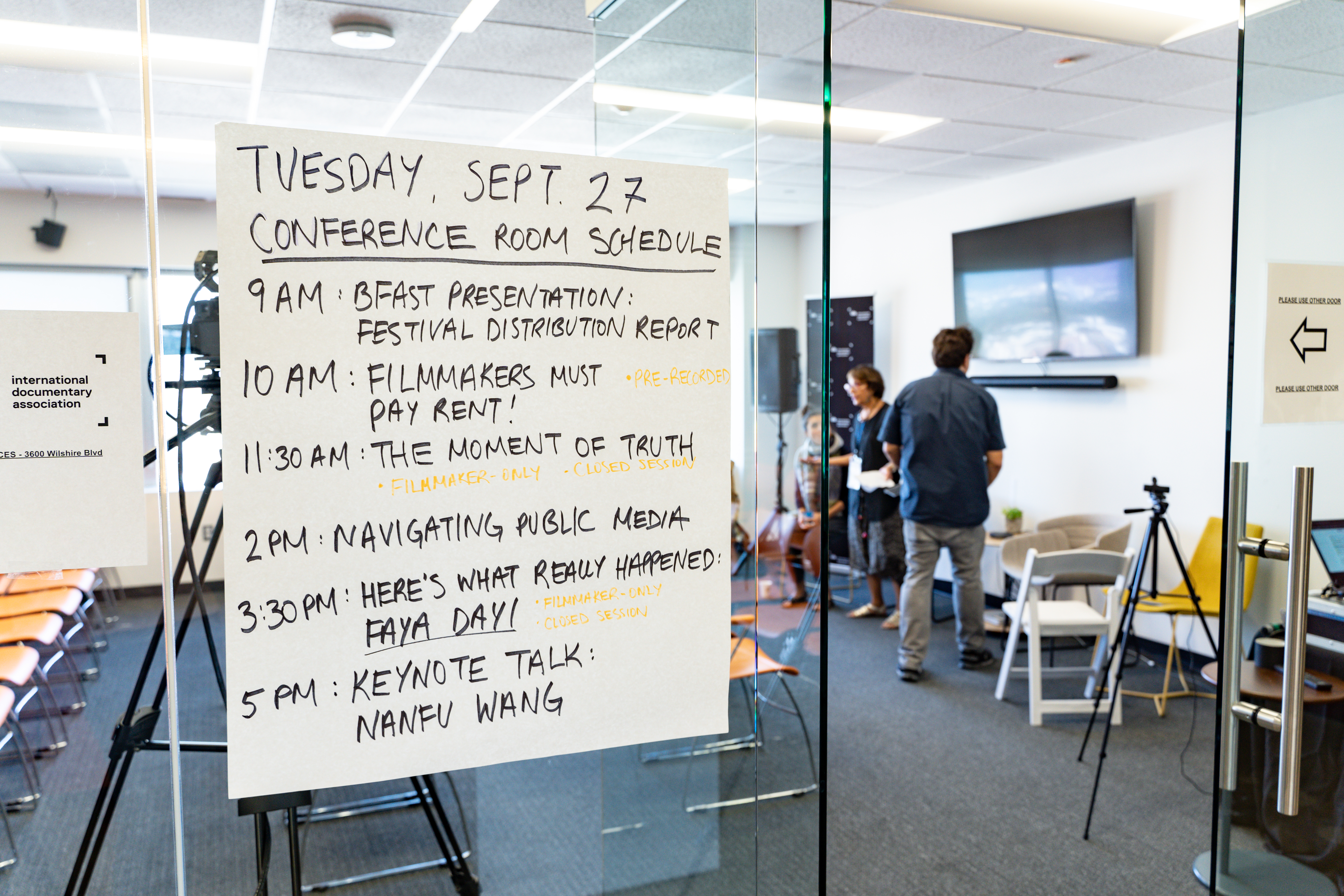

This year’s Getting Real conference was marked by a constant debate around ethical choices in documentary filmmaking. Every aspect of the process was assessed: not only the role of filmmakers but also those of editors, producers, and funders were subjected to critical scrutiny. Even the rights of documentary participants had a space to be debated. But there was a missing link: without deep discussions around actual films that everybody in the room had seen, how could we evaluate documentary ethics from the standpoint of the viewer? In his classic book Le documentaire, un autre cinéma, French

In 2018, I received the “3 Days in Cannes” pass, which allows passionate lovers of cinema from all nationalities and backgrounds between the ages of 18 and 28 to attend the Festival de Cannes. To get the accreditation, I needed to submit an essay about why I loved cinema, and two weeks before the festival opened, I received an email confirming that I had been selected. But soon, my joy turned to anguish; my pass included neither accommodations nor travel. I was a film festival worker in Mexico, and I used that experience to write about my love for cinema; after all, given the working

Last year, after a string of short-term contracts at a screen institute, short film festivals, and a national public broadcaster, I began a concentrated search for stable employment. Over the course of several months, I met with friends and colleagues who recounted their experiences at cultural institutions in Toronto and beyond, searching for job opportunities at organizations that provided at minimum a living wage, a work-life balance, and emotional fulfillment. Instead, I encountered stories about poor management, few opportunities for growth, long hours with low pay, and practices that were questionable at best. Certain organizations offered better benefits, working groups, or prestige, but it soon became evident that every workplace was plagued with the same baseline issues.

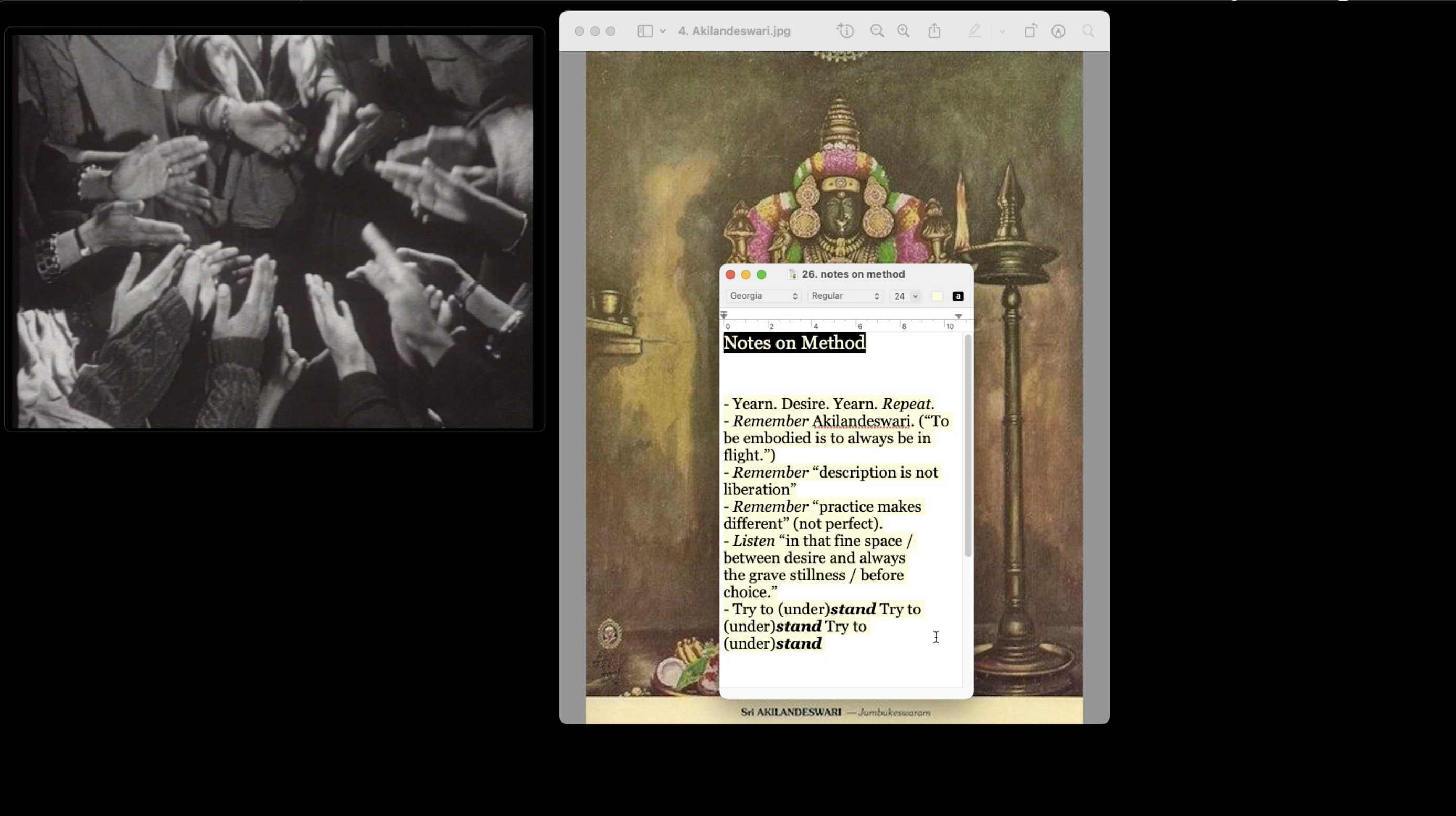

This keynote talk was delivered at Getting Real '22 and was published as part of Documentary's Winter 2023 issue. To view the video recording, click here. I wanted to share with you some stories of my journey of being a documentary filmmaker—particularly the mistakes, the struggles and the failures. Coming to America Before I even began my career, when I came to the US in 2011, I had no idea what a documentary was or what my future would be. I was 26 years old, and all I knew was that I wanted to become a journalist so I could report on the injustice I had witnessed in China. I went to Ohio

This keynote talk was delivered at Getting Real '22 and was published as part of Documentary's Winter 2023 issue. To view the video recording, which includes a brief Q&A between Erika Dilday and IDA's Director of Artist Programs, Abby Sun, click here. Anyone who wants to make change does not have the luxury of being comfortable. Documentary filmmakers know this better than anyone. Filmmakers go to difficult places, ask difficult questions and even put their lives on the line to deliver to audiences the truths that inform us, enlighten us, and hopefully lead us toward real change. But what else

Editor’s Note: Anand Patwardhan, renowned as one of India’s greatest filmmakers, has amassed a considerable body of work over the course of his 50-year career, interrogating the sociopolitical systems that have convulsed India for decades. Patwardhan is the very model of an independent artist—principled about his funding sources, streamlined in his budgeting, focused on the communities he documents. Rather than a keynote address at Getting Real 2022, the programming team devised a keynote conversation with filmmaker/writer Blair McClendon, who generated a stimulating discourse about

Pagination

- Page 1

- Next page