Co-Creation As a Democratic Act: A Conversation with Katerina Cizek and Thomas Allen Harris

By Tom White

Back in 2019—before COVID-19, before the global reckoning on race and racial justice, before January 6, 2021 quickened and amplified the attack-in-progress on democracy—filmmaker Katerina Cizek and educator/author William Uricchio released Collective Wisdom, a field study report produced at Co-Creation Studio at MIT Open Documentary Lab. Cizek, the artistic director/co-founder/executive producer of Co-Creation Studio, and Uricchio, Professor of Comparative Media Studies at MIT and founder/principal investigator of MIT Open Documentary Lab and Co-Creation Studio, researched the field for artists for whom collaborating and decentering were intrinsic to their work. These artists interrogated the idea of the singular author and branched out across communities and artistic and professional disciplines to explore the possibilities of production and practice.

Cizek and Uricchio enlisted the insights of such luminaries in the documentary field as Juanita Anderson, Maria Agui Carter, Detroit Narrative Agency, Thomas Allen Harris, Maori Holmes, Louis Massiah, Cara Mertes, Michèle Stephenson, and Sarah Wolozin, among others, and named them co-authors of the study. They published it online as a work-in-progress, keeping the document open for feedback and review from the greater community.

This fall, Cizek, Uricchio, and the co-authors are gearing for the publication of a trade book version of the field study, through MIT Press, titled Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media for Equity and Justice. The pandemic afforded the authors the opportunity to cite the race for the COVID-19 vaccine—one that entailed a global collaboration among the best and brightest in the medical field—as an example of how co-creation can be truly effective. But co-creation, the authors argue, dates back to the beginning of time, to petroglyphs and prehistoric rock carvings. And we can learn from that ancient dynamic when considering the early days of the space program and the development of the Internet.

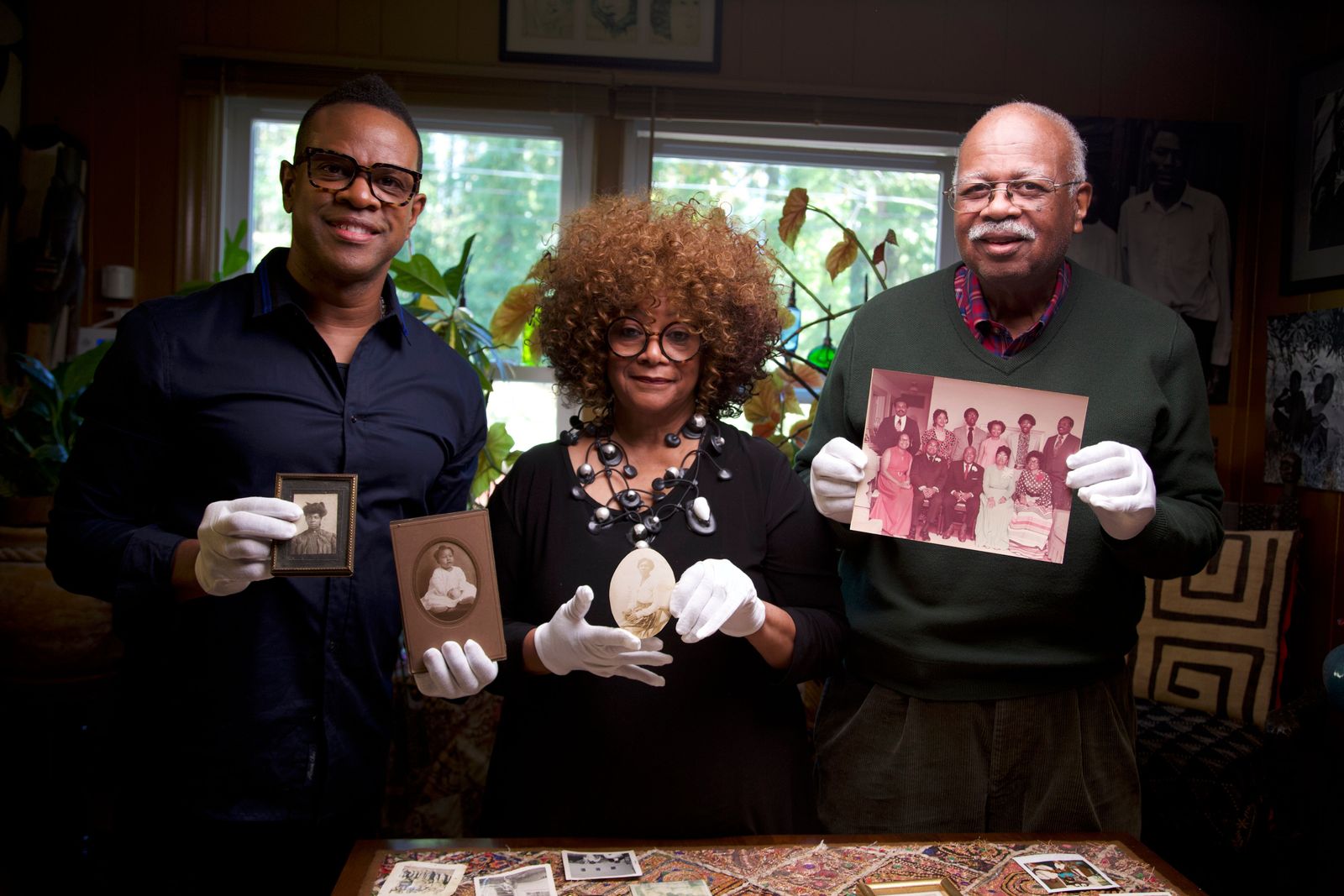

Collective Wisdom co-author Thomas Allen Harris has been deep in the co-creation aesthetic and practice for over a decade, including his Digital Diaspora Family Reunion, which has taken him to thousands of communities across the US, who have shared their family photo albums and the stories behind them. This project has led to collaborations with museums, cultural centers, libraries, senior centers, youth centers, and educational institutions, and an ongoing series of multidisciplinary work. The DDFR online archive houses 3,500 filmed interviews and 30,000 photographs. Harris’ documentary series Family Pictures USA grew out of DDFR, and as a faculty member at Yale University, he recently launched the Family Pictures Institute for Inclusive Storytelling there.

Documentary magazine spoke with Cizek and Harris via Zoom about Collective Wisdom and the potential for co-creation as a full-fledged artistic practice and an instigator for community empowerment.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

D: Kat, I'll start with you, since this is partly your project. When you first reached out to me in 2019 about Collective Wisdom, it was a work in progress. Three years later, you're ready to publish. A lot has happened in the world in the interim—COVID, a global reckoning on racial justice, and an ongoing threat to democracy in America. How did the project change for you and your colleagues in those intervening years?

KAT CIZEK: We published Collective Wisdom as a field study on the MIT Works in Progress site, thinking that that might be the final iteration. It’s meant to be like a peer-review process.

We had put up the field study [on Google Docs], and we'd had all the authors and interviewees given access to feedback before we went public with it. We thought that that was going to be its final resting place; we just wanted to get it out into public. I've had this experience from my own practice, where there's been two responses to this kind of work, especially by people who hold power in the industry. One is, “How could that ever work? How could you ever share IP? How could this actually work legally? It's a nice naïve idea, but good luck.”

And then the other attitude has been, “Oh, we've already done that. You don't need to talk to us about collective process.” And anybody who actually does this work wants to talk about it, because it's never done. It's an imperfect offering. It's something that we need to share and learn from each other all the time about. And how the last two years have played out have—I'd say that that attitude to this kind of work has radically changed. And even the publishing of this book is not something that we anticipated. And the fact that it's publishing as a trade book is also significant.

It's not just an academic, 1,000-issue print; it's actually being put out there for a wider audience. And that's profoundly exciting for us, as people who've been doing this kind of work for decades, to feel like there's reception, there's interest, there's excitement. And there's also concern about how difficult it is, and concern about the cooptation of it, the concern about making sure that it's tied to equity and justice, that it's not just one of these buzzwords that ticks a few boxes for corporations or institutions and that's it.

THOMAS ALLEN HARRIS: In terms of the conversation that I had with the folks that you guys put us in constant communication with—Juanita Anderson, Maria Agui Carter and the other folks—normally we would have people of color coming together in more people-of-color environments to have this kind of conversation. So it was really amazing at MIT to have this moment where even before the racial reckoning, we could actually de-center the master narrative, de-center white supremacy within documentary film, documentary practice, and discussion and theory.

To answer your question quite directly, Tom, it feels like it is right on time. It feels like a date with destiny in some ways. I teach a course at Yale related to my research, which has been focused on community storytelling and a kind of co-creation. And as a filmmaker, I have received support for the Family Pictures Institute for Inclusive Storytelling from Ford and from a variety of foundations. We knock on doors, and the doors seem to be opening. It feels like it is even more critical now, as a model for people to come together and be transparent in power dynamics, be open to listening to one another and navigating new ways of storytelling—not just about the outcome, but about the process and the impact.

For so long, people of color have been ignored, and the kind of deep-seated roots in that kind of collaborative community storytelling process has also received short shrift. Most documentary books don't mention more than one or two people of color.

But I did want to respond to Kat about owning the IP. My process isn't about sharing the IP as much as sharing the credits and being open to people willingly joining me in a kind of collaborative way, as opposed to simply being a subject. So, I think there are different models of co-creation.

KC: There are so many different beautiful ways of sharing the IP: the credit, the decision-making, the governance, the money. There are so many models, and yet I feel like our industry has put aside so many of those to say, There's only one way, and there can only be one name on this because otherwise it's too messy. Maybe the support hasn't changed, but the interest in co-creation has changed in the last two or three years in a significant way. And hopefully, if we do it the right way, the interest will lead to support, but it's a long way to go. I don't think we're at the stage where co-creation models are being picked up by the major institutions or funders in America or anywhere else in the world. But there's certainly more of an openness to hearing about it.

TAH: An example to that is, that I recently submitted several different applications for a new film project, My Mom, The Scientist. And in almost all the applications, there were several questions: What is your relationship to the community? What is your intentionality? And then there's a whole slew of questions that, before 2018, might have been a question that's really more tailored to access, as opposed to, What exactly are you doing and have you thought it through?

D: I do want to ask you, in going through this process of creating the Co-Creation Studio and Collective Wisdom, how has that informed and changed your respective practices as filmmakers?

KC: As a filmmaker, I came out of High Rise both extremely excited by co-creative methodologies and exhausted by them. It's in the margins of the budget, it's kind of hacking our way around these systems to really respect and be driven by the values of co-creation. But also feeling like everybody had to reinvent the wheel all the time. And so that was really the purpose for me to step away from being a maker per se, and creating a hub and creating this conversation around co-creative practices.

It's been an incredible opportunity to be part of MIT Open Documentary Lab. It's not just about working within communities, but also having right relations within community, having that sense of responsibility, accountability, and knowing very clearly who you're in service of when you're doing the work, which is also tied to other disciplines like working as filmmakers with technologists, with people from different epistemologies. Like finding ways to break down the silos between the way we've organized the world. And tying it to the way that we work with technology.

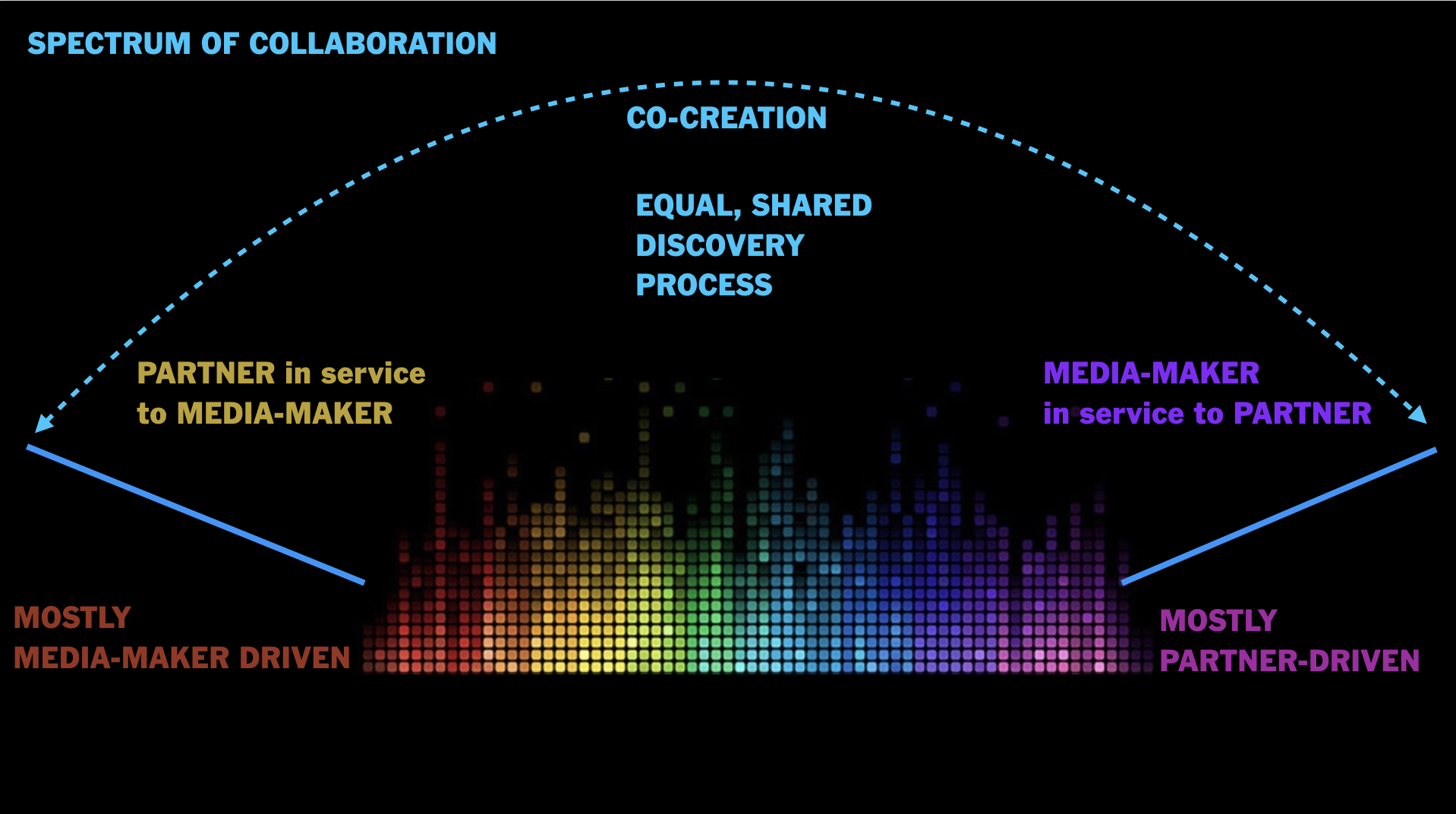

So, as we argue in the book, co-creation is both ancient and something we've actually been doing a lot longer than anything else. But it's also tied to the affordances that these technologies have allowed us to reorganize and work collectively in new ways, as well. And I think that creating that spectrum of co-creation helps make sense of it a bit more; it's not just participatory media. It's not just community-based, media-training workshops on the side; it is profoundly at the core of a new way of engaging with media, with technology, and with democracy and with the way that we want to organize ourselves into the 21st century.

D: Thomas, over to you: How has this process of participating in the creation and development of the Co-Creation Studio and Collective Wisdom changed you as a filmmaker, as an educator, and as the founder of the Storytelling Institute at Yale?

TAH: I would say it gave a kind of affirmation. And that's a touchstone that feels like this is the next level in terms of decolonizing the story and certain storytelling apparati.

But it feels like there is much more of an openness and a vulnerability in terms of practice. I was told about Kat's High Rise project as I was doing research on Digital Diaspora and thinking about different ways it could go as a new media project. So we went through that process.

In terms of thinking about my own practice and passing it on to my students, it feels like we're recreating new models. At the same time, I feel like it's almost going in another kind of direction from this central push around documentary-making now.

Now that it's moved into this uber commercial mode, that is a way to get access to certain types of money in terms of the streamers. So while you do have this kind of support in certain types of foundations, and some public monies, what we're doing is really impacting the field in a very intentional and significant way.

I do think it's disrupting the notion of a kind of master narrative where the person who's making the film is God or that human beings are God. And on the other side, I wonder how much it has the potential to impact the space of the technologists, who tend to be male and white. There's been a lot of discussion around that bias. And I wonder if there's openness in terms of the technology space, and how much work this is doing in that space.

KC: I do think that with the Co-Creation Studio and Collective Wisdom, all of us are stepping out together saying, We do things differently, but there is this genre, there is the spectrum of stuff that's being ignored or erased. It's a portal between conventional documentary, but also, like Thomas said, the technology world. We're sitting at MIT, so we're trying to pour some of this stuff back into that community, that has its own ways of co-creating that we can learn from, and they can learn from ours. But also, culturally, if you think of the media landscape, of the cultural landscape, documentary is such a thin slice of a huge world.

If you look at the gaming industry, that is the future, that is where the money is, that is where the bulk of cultural content is happening. And there has never been a more important time for us to bring equitable, and just, and decolonized documentary practices into that space. And when we say, “Oh, that's not our world, because it's fiction…that’s not our world, because it's video gaming…that's not our world, because it's science fiction…that's not our world, because it's kids doing stuff on devices all day long,” we are missing out on a huge cultural powerhouse that we need to bring our practices into.

D: Along those lines, organizations like Games for Change have been trying to affect what you're talking about. And in a broader scope, I was struck by your executive summary, where you spotlighted the COVID-19 model as an example of co-creation in terms of the efforts made on a global scale to find a vaccination. I thought, This co-creation model is kind of an apotheosis of democracy. It's a democratic act. And as you want this to be a safeguard against co-option, and authority, and control, and ownership, this seems to be the right direction.

TAH: I totally agree with that. I am doing a new film, My Mom, The Scientist, which is a reprisal of an old film. So I'm reading a lot of science literature. I was trained as a scientist, and I stayed in science for 10 years. I've always felt like when I left science, I had to put that part of myself in the closet. So now I’m doing this, and inserting myself into that story. Science can't take place in a test tube or vacuum; it's all about this collaboration and connection.

And so Kat talking about the COVID model makes it really clear. But it's also so much about, as you said, Tom, democracy; we made it here because we had all these different connections and we supported one another. And when I look at the Family Pictures project, when you look at people's family albums, it's the extended family. It's not simply a biological family that's kept the village together, it's really the way in which we could figure out ways of helping one another and coming up with a common vision and supporting that.

KC: It's fascinating to see. We talked about IP, and how the rules that we've built up around these systems are problematic—universities are controlling our emails to one another to share knowledge because it might infringe on the IP. That's scary stuff. And the COVID folks had to really go up against that; that was a serious move that people made and continue to make when you have to choose collaboration over your own career. It's problematic, and we have that as well. These are kind of the trapdoors that we put on ourselves that don't lead to anything good.

D: And in the democratic process, it can sometimes get messy, but in a good way. I take note of the rise of collectives in the documentary world over the past 10 years, which has been a very positive thing and a very necessary thing in terms of empowerment and amplifying voices. In the spirit of collaboration with those entities, some of the people who participated in Collective Wisdom are also part of those groups, but how do you keep the dialogues going with those groups?

KC: There's a shift happening in the States, but also in Canada, where there's holding power to account, and accounting for the fact that work is done collectively. That part hasn't actually changed. Of course, it's always evolving, as are the practices, or the people and the situations within which people practice. And it's just the way that funding and institutions are relating to it is changing.

For example, Sheffield DocFest reached out to me a few months ago, saying that they're noticing so much collective work happening in the last two years. They want to run a program on co-creation. We co-curated this lovely program of films and new media works, and partnered it with older material, to show the history and the legacy of this kind of practice. There is an institutional recognition of collective practice within documentary that's really exciting.

The other thing I can point to is the Peabody Awards. I'm really honored to be a member of the jury for interactive and immersive. So, it's starting to be recognized, maybe not quite front-end enough, like where the money is, but we're getting there.

TAH: I would also add New Frontiers at Sundance. We’ve been working with them and our students in creating ways of thinking about new media-making, with younger generations who might be doing more gaming. Shari Frilot’s work there is really critical, and it’s been amazing to work with her. And also Grace Lee's work around holding PBS to account in terms of people, her amazing intervention around who gets the money at PBS, all that public money and decentering Ken Burns’ one narrative of America.

D: That’s under the auspices of Beyond Inclusion, which is also leading an effort to try to prevail upon the more difficult gatekeepers to penetrate—i.e. the streaming giants—to really open their minds and hearts to this kind of work. And I'm wondering if you all have plans to try to prevail upon those people, to rethink their programming priorities?

KC: These are long-term conversations that we’ve been having for years. And part of the mission of Co-Creation Studio is to help provide those frameworks for that kind of institutional change. That was really one of the recommendations that came out of the report when we first published it online in 2019. And we're already seeing people coming to us, asking, “How can we do this better?” Or even we've had folks come to us and say, “We're doing co-creation.” That's not the conversation we were having five years ago with the same folks.

D: Can you walk us through a recent project that came through the studio, and talk about the particulars—how they came to you, how you all worked with the artists, etc.?

KC: Assia Boundaoui is going to launch a beautiful project called The Inverse Surveillance Project in Bridgeview, Southside Chicago; it’s a co-created project with the Muslim community where she resides in. This project was inspired by her previous film, The Feeling of Being Watched.

Essentially, the film ends with her receiving 30,000 pages of documents, for which she filed via FOIA. But she felt the story wasn't over. And that's one of the key elements of co-creative methodologies: One way of telling the story isn't enough; it often has many, many different iterations and life forms. We invited her to an early workshop of Co-Creation Studio called the Stories of Surveillance Workshop, with Mozilla. And then she came to us a few years later and said, “Out of that workshop, I've got this idea for this evolved media community installation using artificial intelligence to deal with these documents.”

She said it's unfinished business. There's a lot of healing; there's been a lot of trauma with this kind of surveillance on our community. We want to heal, we want to take these documents for ourselves. Assia has been with us as the Ford Just Films Co-Creation Journalism Fellow at Open Documentary Lab. And we did that because we wanted the journalism field to hear that co-creation has a role to play in journalism. Journalism has been the toughest nut to crack; journalists have often said, “Oh, not co-creation, not for us.” And if you actually look at the legacy of journalism and the most powerful forms of journalism today, they are co-created.

So that was the point with that. Assia’s project is with community, taking these documents, creating an art installation, inviting folks; it's a little inspired by Thomas' work as well—bringing in community photographs, family albums, videos, and filling that redacted space in the FBI documents and saying, “You will not define our lives. Our lives come out from our own work, our own stories.” And then there's another artificial intelligence project underway to reinterpret the documents, within the context of surveillance of people of color in America, over the last 100 years.

D: You said that journalism has been a tough area to reach, which does seem counterintuitive, particularly with the advent of VR ten years ago, and The New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian all venturing over the past two decades into VR, short form and in some cases feature-length documentaries. It really did open up their respective milieu to documentary filmmakers. And I think it really enhanced journalism.

To expand on that, what I've always found heartening in being in this field for so long is that it attracts artists from different artistic disciplines, journalists from print and broadcast, and people from different professions such as law and medicine. So, I wonder if you can talk about other areas, beyond journalism, that have opened their doors, that have served to enhance what you're trying to do.

KC: I learned a lot from people in healthcare when I was the National Film Board of Canada's filmmaker in residence for five years, at Michael's Hospital here in Toronto. I noted a lot of the stuff that we took for granted as documentarians or journalists, like consent forms, or informed consent. I was working with nurses and lactation consultants for pregnant women with no fixed address, who were taking that stuff way more seriously than our profession did. So there's a humility with which I worked in that community, and hopefully brought some of those practices into the work that we did at the Film Board. I think we have a lot to learn.

And as Thomas said, with scientists as well, as much as IP can get in the way at the final end, the way in which the work is actually done probably accounts for a collective practice in much more subtle and nuanced ways than we do. And for journalism, I appreciate the moment when documentary started intersecting with journalism, but it's actually further back, when journalism went online. And that was such a profound moment in terms of co-creation and journalism, and the opportunity for communities to be part of telling their own story.

And that's what's fueling the incredible powerhouses now in journalism for co-creation, with the Pegasus project, these large trans-national groups, working with people like Bellingcat to uncover and investigate huge surveillance projects that are much bigger than any one entity. So if one newspaper gets shut down by the government in one country, others can continue the work. And that's fundamental to the way that we need to address some of these large anti-democratic issues in the world today.

D: I wanted to get a sense from both of you of where you see this going over the next five years, both the studio, and the principles and ideas behind Collective Wisdom.

TAH: We're doing this project, the Family Pictures Institute for Inclusive Storytelling. As Kat was saying, a lot of people have been inspired by this work since we've been doing it, in a much more public way, with Digital Diaspora since 2008. We were getting emails from dancers, people working in theater, people working in healthcare. I had a conversation with a nurse around how our methodology helps people understand or be better able to track their health, particularly among communities of color that might not necessarily have been going to doctors in the same kind of way or might be turned off from doctors because of racism, projection and stereotype.

The health community can use the photographs to track certain things—memories, but also certain aspects of family health, and stories. That's one of the reasons we created the Family Pictures Institute for Inclusive Storytelling, but also there's a denial of the narratives of people of color and women, in terms of how we have impacted culture, impacted science. When we did the PBS series Family Pictures USA in Detroit, for instance, out of 100 different families, 40% of them came in talking about women entrepreneurs in Detroit. This was something we did not even actually put a call out to, but it was just a dominant story in this crowdsourced story. Normally we hear about Ford and the big guys with the big cars and the factories, but to have these women entrepreneurs, it was going all the way back.

Now we're rolling it out to five to seven cities; we're starting in Pittsburgh. I'm working with the Heinz Endowments, and we're talking to several other foundations. We're working to seed the culture so that people can talk about history to the fullness of who we are, and how we got here, even at a time when it's illegal in 20-plus states to do so because it goes against white supremacy.

We want to have people come together and talk about their histories; in some ways, it’s a truth-and-reconciliation kind of happening. We’re in the process of sharing through this methodology that we developed. And so, hopefully, it'll provide a common ground, while at the same time uplift those narratives that undergird the whole notion of replacement theory and a lot of this backlash with regards to white supremacy that is literally killing us, and killing the planet.

Carnegie Mellon University will be teaching a course around the project, as well [University of Pittsburgh]; it’s a co-course. We're working with churches, synagogues, and mosques; we're also working with various media collectives and museums, and libraries.

D: Any final thoughts about your work, about Collective Wisdom and Co-Creation Studio?

KC: The work continues, and continues to evolve; the book is really a sign to point to, for the community, hopefully. I certainly feel less alone, having done this work and having had the honor and the privilege of talking to people who do this kind of thing day in, day out.

So, it becomes a foundation for people to continue the work and evolve it and develop it. It's not the final word; it's an imperfect offering. But it hopefully propels us into new generations, like new shorthand, so we don't have to go back to the beginning over and over again and restart from zero, that we all understand that this history exists, that we learn from it, and we move forward instead of constantly battling backward.

TAH: And I would just add that just the notion of me and we, and the relationship between me and we, are so pivotal when one thinks about co-creation; it shifts that narrative that is so dominant in our culture: “I'm an island, I made it on my own, I don't have any responsibility.”

I hope the book will spur more conferences around co-creation and pull in more people in technology spaces, science spaces, art spaces, journalism, and law. It’s so important in thinking about, How do we come together to amplify social justice, and visions for a just, equitable, and sustainable future?

Tom White is the Editor of Documentary magazine.