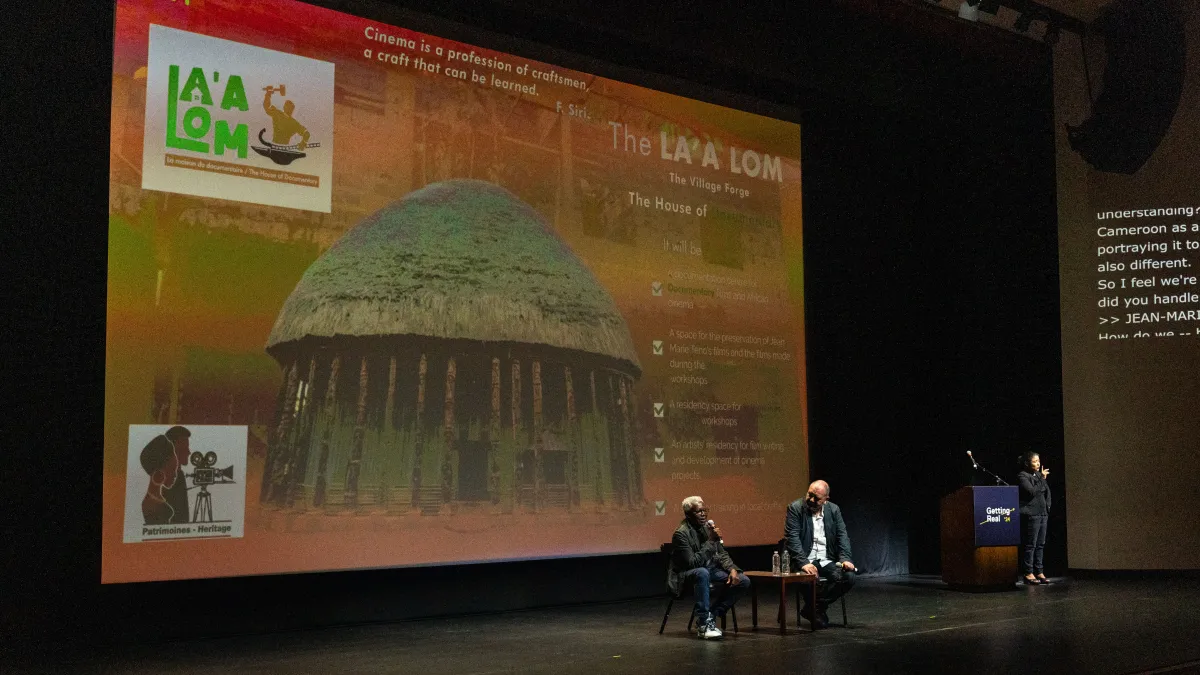

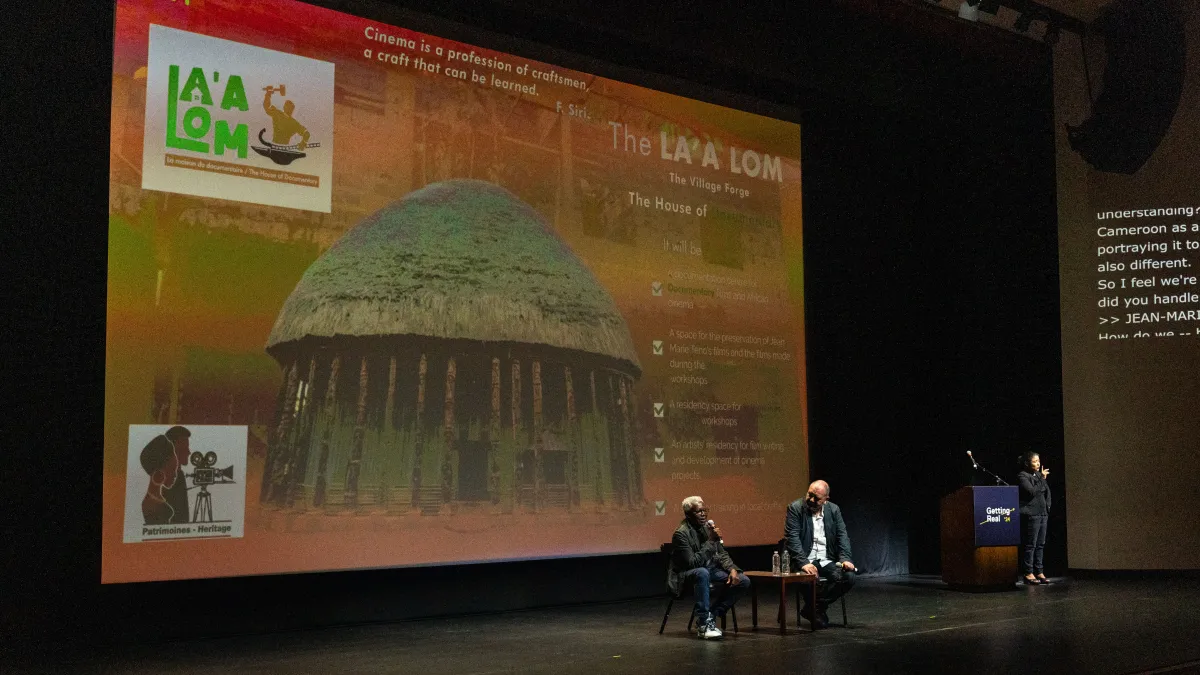

Jean-Marie Teno (L) and Orwa Nyrabia (R). Image credit: Urbanite LA

Jean-Marie Teno is Africa’s preeminent documentary filmmaker. With a critical eye and a sharp wit, he questions the established truth, exposes the censored stories, and examines the past to comprehend the complex realities of Africa’s present. Teno’s films have been honored at festivals worldwide, and he has been a guest of the Flaherty Seminar, an artist in residence at CalArts and the Pacific Film Archives in Berkeley, and a lecturer at many universities. He is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ documentary branch.

Teno’s best-known film is Africa, I Will Fleece You (1992). Viewed now, the feature remains an astonishing, critical, and edifying excavation of the effects of colonialism on post-independence nation-building projects. Teno’s own narration guides us through the film’s focus on a century of Cameroonian history, contrasting insider-outsider views of nation-building, culture, and legacy. It’s regularly taught in third cinema and post-colonial studies classes.

Although Teno has also produced films for other filmmakers for decades, in recent years he has turned his attention more squarely on the project of training documentary filmmakers. In 2018, Teno started annual months-long documentary filmmaking workshops under the banner of his Bandjoun Film Studio. Two years ago, he started construction on La’a Lom, a brick and mortar cinema and film center. In 2020 with film scholar Melissa Thackway, Teno co-authored a monograph of his own work and political cinema, titled Reel Resistance: The Cinema of Jean-Marie Teno.

On the last day of Getting Real ’24, Teno was interviewed for a keynote talk by Orwa Nyrabia, IDFA’s artistic director since 2018. Along the way, Teno dives into the innovative form of his early films, the many ways he’s moved resources and knowledge from European and U.S. institutions back to Cameroon, and his work leading documentary trainings. The following is an edited version of their conversation and audience Q&A. —Abby Sun

ORWA NYRABIA: I’m going to be having a chat with one of my heroes, and it’s a wonderful thing when one is invited to talk to one of those heroes. Jean-Marie Teno is a filmmaker. He makes brilliant films. And he made many films in his country of Cameroon that meant so much to me, growing up in film. He was always one of the few from the African continent who I was following, watching his films whenever I could.

At the time, it took a lot of work because you had to send endless emails to many people who did not reply, until somebody replied and promised you a DVD screener. Then you got the DVD screener, and then you discover Africa in a way that has nothing to do with the Africa one sees on television. It’s an Africa that is real, a filmmaker’s gaze that is organic and powerful, so loving, and that does not contribute to tropes and stereotypes.

The question of stereotyping, of looking at Africa and African people through problematic or colonial eyes is not there. So it is not that it is a decolonized cinema. It is a cinema that doesn’t care about the question of a colonial gaze or a decolonial gaze. It is African cinema. It is not anything else. So after all of that, I would love to introduce this wonderful hero to you.

Jean-Marie, I’m starting at the beginning. There was a young Jean-Marie in Cameroon heading to the airport. Why was he heading to the airport? And what did he want? What did he imagine on arrival after he took a plane out of the country?

JEAN-MARIE TENO: I found myself having a scholarship to go to Great Britain, and I boarded the plane and then it arrived, and it was 10:00 p.m. It was still daylight. I was just wondering, where the hell am I? Normally I know that at 6:00 p.m. it’s night where I grew up.

I discovered some obvious differences, and I didn’t even expect anything because we studied Europe in school—we knew so much about Europe and so little about our own country. So I was almost in a familiar space when I arrived in Great Britain. And then when I arrived in Paris, it was even more familiar because I knew almost everything about France, but so little about Cameroon.

ON: I remember that you did not first get this scholarship to study filmmaking.

JMT: Yes. When you receive a scholarship, it’s almost like a pass that allows you to go, and it could be on chemistry, on physics, on anything. I received a scholarship to do electrical engineering, and I spent only one year in England because when I got to England I discovered the political movement in the student union and all these big discourses. And that was more interesting for me than going into doing these electrical things.

And the British consul was giving me a hard time. So I just said, okay, well, I’m returning home. So I returned to Cameroon when school started and I was in the neighborhood. People say, “You went to London, and you came back!” No one comes back. Why did you come back? So that was my first experiment, going to Europe and coming back and then starting from scratch, working for the radio station and really enjoying being in the neighborhood.

ON: And then film happened.

JMT: And then film happened. There was a television station that was starting in Cameroon. I was among those who were selected to go to France to train for television. And when I finished, the television was not in Cameroon yet. So I was working in the television station in France in the technical part. I bought a 16-millimeter camera secondhand. I started making my own films on 16mm, processing them in a lab and going back and forth. We had a newspaper with some friends in Paris called Bwana. And I was writing for film at that time without any real training, but I loved film, I watched film, and I was writing. I’m so embarrassed to even read the things that I was writing at that time, but we were writing about film.

ON: And then you took the 16mm camera back home?

JMT: No, I stayed in France actually. And because I was writing for film, I went to FESPACO in 1983, and there I met Ousmane Sembène, I met Souleymane Cissé, I met the first generation of African filmmakers. I had seen almost everything that was made on the continent by then. And I had a conversation with Souleymane Cissé, the one who did Finye (1982) and Baara (1978). And we had a half-hour conversation I recorded on a tape recorder.

And after the tape was finished, Souleymane said to me, “But you are not a journalist, you should be making films. You cannot be continuing to just ask these questions because the questions you’re asking about films are really not the questions that the journalists usually ask.” And he said, “We are not so many of us making films. You should be making films.”

And that’s when I left. I said, “If Souleymane Cissé, that I admire having seen so many of his films, says so, maybe there is something here.” And with the camera that I had, I started filming my friends in Paris, and that’s how a few months later I made my first film. After that, because I was working for the television, we had one month’s leave. I went with that camera home, and I made my first short film, Homage (1985).

ON: I remember you speaking about how making your first film was in a way driven by a feeling of discomfort.

JMT: Yes, discomfort has always been present in motivating me into addressing issues. And my very first film, the discomfort was that my father passed away. I was the eldest son. They kept the funeral for five years for me to return home.

And then I came home with my 16mm camera, and I was filming what was happening. The discomfort was really trying to understand the kind of conversation we used to have with my father, trying to pay homage to him. And at the same time asking myself, “If I’m going to be making films, what kind of film am I going to be making? What footsteps am I going to trace?”

In African cinema there were not many people who were making documentary films. And at the same time, I had many good friends who were stand-up comedians. And for me it was a nice way to combine comedy, because I love comedy, and talking about the things that really matter.

In the film, I invented a dialogue between two people talking. You never see them. And in this dialogue, you have the everyday images. Then at the end, there is the twist that really says that one of the characters is me. And actually, the two characters are two faces of who I was: the one who stayed in the village, and the one who went to the city and then to Europe. And there was a confrontation between—what we were calling at that time—tradition and modernity.

I watched Homage again 30 years after, at a point when I was asking myself, “Do I really want to continue making films?” When I watched Homage again, I really understood why I wanted to make film and the kind of playfulness or amusement that cinema was. If I’m going to take one hour of people’s time, what am I going to be telling them? And this question became more and more important to the continuation of my career.

ON: The question of playfulness is often put in contradiction with the question of documentary. I can’t help but remember that brilliant phrase from Safi Faye, may she rest in peace. Safi Faye was a great Senegalese filmmaker who passed away less than two years ago. When she said that she believed that differentiating or separating fiction from documentary needs so much privilege, and that to her, no African filmmaker can ever do that—

JMT: Absolutely.

ON: We cannot see documentary as not fiction or fiction as not documentary.

JMT: Absolutely.

ON: So this question of playfulness and comedy there takes me here to the question of reality. There is a terrible reality in front of you, but you are processing it through sarcasm and irony and a certain joy, despite all of it. What can you tell us about this? Because it’s very clear in your first feature film [Bikutsi Water Blues, 1988].

JMT: We can also add the entertainment part because we grew up watching a lot of Bollywood films. In these films, there are always some moments where the dancing, the music, continue to bring the story. For us it was almost a way of telling stories and really allowing people to relax, [a way to] prepare them for something very harsh by giving them a little bit of amusement.

When you listen to storytellers, and when you even listen to old people talk in my village for instance, they always mix songs. It’s never a linear kind of conversation. People start something and when they want to digress, it can be a song, it can be a... All these elements contribute to storytelling and to telling the story that they want to tell at that moment.

And we approached film as Africans from a place where we always said, “What do we really bring to the narrative?” You cannot always be going through the three acts or five-act structure and all these that they keep teaching in schools. And so at one point you just say, “I want to tell a story.”

And with telling the story, who am I to tell you that story? What are the elements you need to have for your story to exist? And then you start building it up. And from time to time you make pause, you prepare some effect. It’s just playing. And playing with the public, entering into a conversation, using the music in a way.

And in my first feature film, Bikutsi Water Blues, I had a band who was playing, so music was always a part. The fictional part was for me the element to allow the hard documentary part. Because people kept saying to me, “Well, you are going to talk about water, about trash. We see that every day. That cannot be a film.”

So I had to create a structure where a kid comes home and he’s telling what happened at school. And create the kind of narration that will allow people to enter into the film so that they can face their own reality without having the feeling that you are hammering it onto them. And you have to have one of the biggest crazy bands that existed at the time, Les Têtes Brûlées, with all these gimmicks on stage. And people were shocked to see them.

All these element contribute to a way of entrusting people, challenging what they’re expecting, and giving them the chance to have a good time watching a documentary. Because they always thought, “When are you going to make a film?” And when I showed Bikutsi Water Blues in Cameroon in ’89, there was half an hour of trailers. There was Rambo, there were American action films. And then I show Bikutsi Water Blues.

And people are just saying, “When are you going to make a film like these films with fighting, with action?” And I said, “You’re going to have the documentary.” But when the Les Têtes Brûlées were there, and suddenly... That was a long time ago, and people gradually started getting used to looking at their own reality. Especially in a place where censorship is so strong and when you’re not allowed to talk about what you’re seeing.

ON: I will get to that soon, being not allowed. But I will start with a topic so dear to me, which is the three-act structure. You had a career of fighting with colonial funding. You’ve always been famously angry about colonial funders.

JMT: Yes. I’ve not always been angry with them. The thing is when I did Afrique, je te plumerai (1992)—

ON: The English title of this film is not as good as the French, but it is Africa, I Will Fleece You.

JMT: Yes. Or Africa, I Will Pluck You Clean. Many people translated it.

When I started, it was a film about reading—how writers witness their time during the colonial period. Someone told me later that when you want to address hard issues, just don’t present them too harsh. Just say you’re going to do something nice.

I had a lot of funding because it was about reading and writing. And of course the colonial funders really were champions of teaching us how to read and how to write. And gradually, when we started going a little deeper, when they saw Afrique, je te plumerai, they say, “What? This is where we put all this funding?” And it was really a shock and many people predicted that I will never get any funds from them anymore. But I just say, “Well, c’est la vie. So…”

And then fortunately with ARTE from Germany, ZDF, I had Eckart Stein, who is not there anymore. He had a slot called The Small Window where I was fortunate to have a few films that were commissioned by him. That allowed me to continue making films without depending on the institutional funders in France.

ON: If we put aside the role of Europe or colonialism and funding and go to what’s happening at home, the limitations of work—because these days we’re only talking about money, I think—there is no money for your work in Cameroon, no funding. But there is more than that. There is also pressure, limitations. How was this journey through the different changes in Cameroon’s political map?

JMT: The political map in Cameroon hasn’t changed much. Cameroon became “independent,” under brackets, in 1960. Since, we’ve had two presidents and the actual current president, who is probably 95, was previously the prime minister. He has been in power for almost 60 years. So, things haven’t been really changing.

And the political situation is that when we started making films in the late eighties and in the nineties, people would say, “No, you are exaggerating, you are showing trash. But no, that cannot be the reality.”

We’re talking about water in ’88, all the problems that water will bring. At that time there were still some public water supplies, but all of these have disappeared. And now everybody is supposed to have water in the house. But when I’m living in Cameroon, every morning you have to turn on the tap. If there is water, you put water in buckets and you save because you don’t know if in two or three hours’ time, they’re not going to cut water.

It’s almost like the shortage of the basic necessities have become a way to keep people under pressure. I think it’s a deliberate policy not to give that so people can live and can be productive and can move forward. Because Africa is a place where it needs to be the place of the absence, the place of need, where you don’t have things. Yet we are going back and saying we’re going to transform that. But to transform that, we need to have some responsible leadership.

There is some light coming up. Senegal, we didn’t think that in Senegal things could change. And yet you have a new generation arriving in Senegal. So these things are happening now, and we are hoping that it’s going to continue. This is probably one of the turning points.

ON: In the past two years, you’ve been working hard on a project that I believe is inspiring. That is you voluntarily taking the responsibility of starting a film school in Cameroon for the new generation of Cameroonians. Putting all your knowledge and what you have achieved in your life at the service of potential new filmmaking in the country. I’ll ask our friends in the tech control to show the slides.

JMT: Yes, for this notion of transmission, there are ages. The age where you learn, the age where you enjoy, and the age where you start giving to others so that others can grow also.

In 2015, I was invited by some young filmmakers to be part of the group to lead them into documentary. They were trying to make documentaries, and I was appalled by the kind of subject that they were addressing. It was so complicated, so circumvoluted.

And I just sat there and said, “Look, let’s go for a walk in the street, there are so many things that you can talk about. Why is it that all your projects seem so absurd, so complicated?” And they said, “Well, we want a film that can have a chance to be at IDFA, at Berlin, at all these places.”

ON: [Laughter.] I trusted you, man.

JMT: And I said, “Well come on, that cannot be the…” And they said, “But that’s when people come. They all want us to do this kind of very complex thing.” And I said, “Well maybe I’ll come back again, and we work.” But when I said that, people started being scared, saying, “Oh, he’s going to make political film, you’re going to make political training.”

So someone said, “Well, why not do something about heritage?” That’s why I said I’m going to train people in making documentaries, but the topic was going to be heritage, our heritage. No one is talking about it, everything is disappearing. If you have a subject in relationship with the heritage, you come, and we train you into doing that. And of course in heritage you can put everything. Memory, history, political, all the questions.

At that time I was at Wellesley College as a fellow. And at Emerson they were getting rid of HD cameras, and one of my friends was teaching there. They said, “Oh, we are getting rid all these cameras.” So I went and I applied, and I got 10 cameras that I brought home. And it’s with these 10 cameras that I started the training.

It was amazing because you had people who had a master’s in film production in the university who had never touched a camera. And so they came to my place and they held one. I did the first one—I was the only one working with them. There were five of them. We made five short films because I wanted everyone to make a film. It’s a three-month workshop where you go from an idea, gradually define a film project, then they shoot, and then they come back to edit. And in the course of three months they make a film of between 20 to 30 minutes, maximum.

We did it the first year, the second year. And then there was COVID, and we started again in 2021. And now the fourth edition was 2023. That finished a few weeks ago. And in the course of four years, we have made 22 short films.

It’s free tuition. I raise funds and people come. We live in the same place. They eat, they sleep, and they watch films. Because I bring films from all over so that people can watch films. They go and they make their film, and at the end they have one film that they can show to do applications for other projects.

The big part of my budget was always finding a place where we can all be living together, the food. And so I had this old barn where I grew up. Two years ago I just said, “Why not transform it and turn it into the center where everything will happen?” And the place where also I will store my work because Rochester—and many places in the U.S.— want to have all my archival work. And I’m saying, maybe it’s time for people to come to Cameroon to a place and find my work where the work is based.

So this place is also going to be the place where my work will be. And I’m slowly building this place. We have put the roof on, there’ll be space for people to stay. There’ll be a place for working. We’ll have a small library. And then when we are not doing workshops, people can come and develop their projects. We’re trying to make... I’m not calling it really a school because school means you have a professor.

It’s just a place where those who have more experience are accompanying those who are starting, in a way like they are learning but not having a magistral course. They come with the idea to make a film. And you go through the different steps, and the theory comes gradually whenever you are encountering them.

We are doing a companionship, in a way. And I will be bringing people from all over the world to come and stay and share their knowledge and—

ON: —and teach how to make three-act films.

JMT: And that will be challenging most of the time because whenever they come and make the theory, we’ll just say, “Okay, you do that, but this is a big storyteller from here. What does he think about this three-act thing?” And he might just come and say, “Fuck the three-act thing.”

ON: You can join us in the discussion. Raise your hand so that you get a microphone. And you’re very welcome to comment, to reflect, to ask a question. There.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hello Jean-Marie, thank you so much. I’m originally from India and I’m based here now. I’m connecting so much to everything you’re saying because I grew up watching Bollywood, and for me, like for every Indian and everybody outside the U.S. who doesn’t know Bollywood, it does have a big impact on our lives.

One thing I wanted to understand from you is a challenge I’m facing as a filmmaker. In my head I have a certain idea of India and I have a certain way of thinking about my subjects. But then the Western world has a very different perception of my country. If I shoot it in a certain way, the way an Indian would shoot it, it wouldn’t really be acceptable to the Western eye.

How did you handle those kinds of emotions and that understanding? Because your understanding of Cameroon as a local is very different, but then portraying it to the Western eye just for the funding is also different. I feel we are always in a colonial flux. How did you handle that as a filmmaker?

JMT: Well, that’s a tough question. How do I handle that? But do I really handle that? At one point I just said, “Really, I don’t care.”

At the beginning, people came to me when I was making films on urban Africa. It was also the time when there were very famous African filmmakers who were making the films about the village. And people would say, “But there are no cities, there are no people living in cities in Africa. Why are you bringing us all these questions about urban Africa? That doesn’t exist. We want the village, we want the calabash, we want all these. These are the Africa we want.” I just said, “Okay.”

What else can you say when people say things like that? So I just went on and made films, hoping that one day things will change. And things have changed. At the same time, when I made films, my films were very critically attacked so often. It didn’t prevent me from making films because if I was waiting for their approval, to celebrate me, I would have stopped for a long time.

And there were some of my colleagues that I can consider were mediocre, but they were celebrated, completely celebrated. And that was okay, and we lived together, and so, everyone has to decide who he or she is going to be listening to.

Afrique, je te plumerai is a 30-something-years-old film. And when I finished that film, people said, “That’s going to be the biggest crap that has ever been made.” Some people said, “Oh, that’s just collage, it’s not cinema.” And even today people are watching it again. That’s how things go. Okay.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Thank you so much for everything you shared. My question is about the image behind you and the work you’ve shared about bridging and connecting communities. I want to get more insight from you in terms of how you imagine this extending to the continent and to other countries around the continent, and how you potentially see this space being a wave that starts in other countries as well.

As a fellow African, Ethiopian, we’ve been talking about gathering spaces for the past few days, and I imagine that actually informs the location. And the dislocation of those spaces of gathering actually inform the nature of the conversation we would be having.

I feel very fortunate to be able to be here with you. I also question if the nature of our conversation and the nature of the presentation and everything would be different if we had these spaces on the continent itself. I really want to take your idea on this. Thank you so much.

JMT: Yes, yes. Actually, most of the things that are happening now, it’s almost like 30 years ago when African filmmakers gathered. And for me, I have a great example. You’re from Ethiopia. Haile Gerima has been so instrumental in working with us, really making us realize what cinema could be.

There were organizations on the continent, the FEPACI [Pan African Federation of Filmmakers], they were gathering. They even made this manifesto in Algeria in 1973. And I wish every young African filmmaker could read that manifesto because it’s such an important... In Algeria in 1973, to really say what cinema should be for the continent and how we could be bridging, going from Senegal to Ethiopia, having this federation, and meeting at FESPACO.

These conversations have always existed, but it’s now that we are being gradually segmented. And of course, the arrival of Nollywood has brought a very important dislocation or disturbance in all this. Because Nollywood came and really said, “Well, the market.” But it was also salutary because they said that we have our market locally, we also have to not neglect that market. And they managed to find a way, a market locally. But at the same time, what was the kind of product that we were putting in that market?

So these conversations are going on, but the organizations carrying them, now we have probably DocA [Documentary Africa], which is trying to really revamp these kind of discussions. But the continent is big. And in different countries, the governments are not the same, are not allowing the same kind of space for people to express themselves. The conversation is on, actually. That’s what I can say about that.

ON: Do you know what FESPACO is? Raise your hand. Okay. Can you briefly say what FESPACO is?

JMT: Yes. FESPACO is the Festival Pan-African du Cinema de Ouagadougou [Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou]. It was created in 1969 by Sembène and a group of African filmmakers to have a space where they could show film, talk about film, and develop strategies so that cinema could occupy an important place in people’s lives—especially considering the level of illiteracy that came after the independencies. So cinema was supposed to accompany the countries in their development.

ON: And FESPACO still exists, still runs every year, and is a very strong African festival in Burkina Faso. I have to apologize, first to you, because we’re out of time. I hope that you can catch Jean-Marie outside. To everybody, thank you very much. Jean-Marie, it’s never enough.

JMT: Can I say one word? I have to say the last word because actually, coming here for me was really such a treat. Because having been making films that were always in the margin and going to all these festivals where documentary was always not really there, and then arriving here and being in the middle of a community of people sharing the same interest and challenges… really, it was something important. Getting Real was really an important moment for me.

It’s happening here in the U.S., a place where no one wants to look at the reality. And I think Getting Real is taking us back to really questioning and talking about what is happening now. And we need to transform that by making images.

Orwa Nyrabia is the artistic director of IDFA. Previously, he was a film producer, festival director, journalist, and assistant director.

Jean-Marie Teno has been producing and directing social issue films on the colonial and post-colonial history of Africa for over 35 years for television broadcast and theatrical release. His films are noted for their personal and original approach to issues of race, cultural identity, African history, and contemporary politics.