Making a Production is Documentary’s strand of in-depth profiles featuring production companies that make critically-acclaimed nonfiction film and media in innovative ways. These pieces probe the creative decisions, financial structures, and talent development that sustain their work—revealing both infrastructural challenges and industry opportunities that exist for documentarians.

Monday, November 3, 2024. The six current members of PINKS, short for “pink skirt,” gather around a communal table for their weekly meeting. Two cats freely roam around the table, gently stepping on open laptops while they exchange quick life updates. Nungcool, who takes care of most of the administrative and accounting-related duties, leads the meeting with the priority agenda of the day: the upcoming world premiere of Kim Ilrhan’s latest documentary, Edhi Alice (2024) at IDFA.

The film revolves around queer rights activist Edhi and gaffer Alice, both trans women. The first half, which tells Edhi’s story, dovetails into Alice’s at its midway point as the film takes a meta-turn by revealing the latter’s involvement in it as a lighting technician. Although the two women had been on different life paths from one another before transitioning, the film beautifully emphasizes how the existence of Edhi, the older of the two, enables Alice to imagine growing old and building her life well into her 40s.

“We are preparing a pop-up event to go alongside the screening,” says Kwon Ohyeon, the youngest of the six.

The documentary’s titular stars will be serving beverages for the guests. “Maybe we should incorporate K-pop into our event,” adds Ohyeon.

Kim Ilrhan (also spelled Kim Il-ran) quickly interjects with skepticism: “Do we really have to do that?” Pressured to make the most out of the premiere at a major overseas festival, with which they are relatively inexperienced, the six members discuss strategies for the pop-up with thoughtful consideration and eagerness.

Next on their agenda is a discussion around grant applications and seeking out new funding sources. In addition to being a documentary collective, PINKS (subtitled “Solidarity for Sexually Minor Cultures & Human Rights”) is a renowned queer feminist organization that fights for gender equality, legal reforms for sexual minorities, and labor movements in South Korea. While they have been able to get by so far on government and nonprofit funding and monthly donations from grassroots supporters, they now find themselves in a place where greater financial security is necessary not only for sustainability but also for more ambitious projects they would like to take on.

PINKS office opening ceremony in 2016.

Jo Hyeyoung (L) and Kim Ilrhan (R) promoting the screening of Mamasang: Remember Me This Way at the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival in 2004.

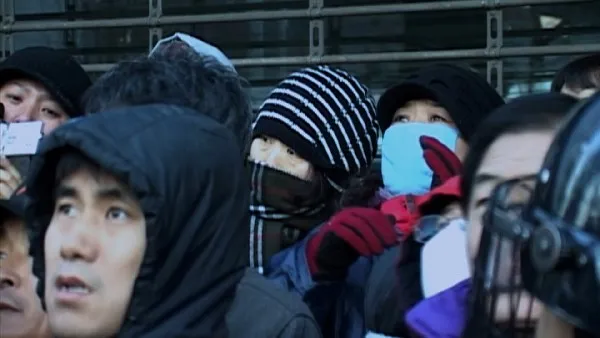

2022 protest for the enactment of the Anti-Discrimination Law in front of the National Assembly.

All of us in the so-called ‘young feminist’ circles lacked the organizational infrastructure to wage more coordinated political struggles. All we had was our intense political conviction, so our actions could only be spontaneous.

Kim Ilrhan

It takes incredible perseverance for any entity to stay in business for more than 20 years. This is especially true of PINKS, which initially began as a queer feminist activist group. In 2002, Kim, then a graduate student, organized a seminar on psychoanalytic feminism where she met the future collective member Han Younghee. Together, along with now-former members Lee Hyuk-sang, Park Jin-young, Cho Hye-young, and Hong Ji-yoo, they formed a collective in 2004 to put theory into practice.

Dozens of grassroots activist groups emerged in South Korea around this time; Unni Network, Ecofeminist Alliance, and Women’s Liberation Front were some of the more noticeable groups in the Korean feminist space. “The feminist collectives from the early aughts departed from our predecessors in that we banded together around the slogan ‘the personal is political’ rather than trying to change political institutions,” Han explains. As such, they favored decentralization of power within a collective and strived to overcome what they deemed to be the restrictions of political representation.

Kim remembers PINKS’s early years as a turbulent time marked by constant organizational challenges and identity crises. “All of us in the so-called ‘young feminist’ circles lacked the organizational infrastructure to wage more coordinated political struggles. All we had was our intense political conviction, so our actions could only be spontaneous.”

Many of the activist groups tried to create organizational structures that would broaden their activism without compromising their opposition to hierarchy, yet most failed and eventually disintegrated. Though PINKS didn’t solidify its structure until 2016, when Byun Gyu-ri and Nungcool joined, it is one of the very few still remaining.

***

Mamasang: Remember Me This Way.

Mamasang: Remember Me This Way.

Artists, including Nungcool (far R), performing at the Yongsan District 4 eviction protest site in 2009.

PINKS’s first documentary, Mamasang: Remember Me This Way (2005), came about by chance. Co-directed by Kim Ilrhan and former member Cho Hye-young, who is now a renowned film critic, the film, commissioned by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, was born out of a series of interviews and field research for a survey report on interracial children of licensed sex workers in U.S. military camp towns. Kim floated the idea of turning the findings into a documentary as she believed that more could—and perhaps should—be done with the material than creating a bureaucratic report. The funding for the project came from the PINKS members’ own pockets, merch sales at the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival (SIWFF), and donations from like-minded activist groups such as the Korean Lesbian Counseling Center.

Neither Kim nor Cho had any prior filmmaking experience, and they approached this undertaking as an ethnographic study that happened to be in the form of moving images. They learned the basics of filmmaking as they went, and the sense of technical discovery that permeates the film neatly rhymes with their grip on documentarian ethics that mature over the course of the production. Former PINKS member Park Jin-young, now a programmer at Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival, believes that how Remember Me This Way grapples with the question of representing the socially illegible makes it the group’s most “modern” work. The film premiered and won the Women’s News Award at SIWFF in 2005.

That same year, PINKS was invited to participate in the Democratic Labor Party’s newly formed Committee for Sexual Minorities, which sought to put together a survey report on legal challenges and structural injustices faced by transgender people in Korea. The completion of the survey led to the establishment of a task force within the Party to advocate for legal reforms to make gender marker changes more accessible. As was the case with her first documentary, Kim felt that the field research and interviews conducted as part of the report should be turned into a film. Like its predecessor, PINKS’s second film, 3xFTM (2008), which documents three trans men and their daily struggles in a transphobic society, was born out of a sociological assignment in service of policy reforms.

Between her first and second films, Kim spent a lot of time wrestling with her social positionality in relation to her subjects. “As I was working on 3xFTM, I thought to myself, ‘Do I even know what it means to represent the other?’ There I was, a cisgender feminist documenting the daily struggles of trans men,” Kim recalls. The experience of making her second film encouraged her to ponder deeply about documentary as a medium and eventually led her to think of herself as a documentarian for the first time. “Labeling myself as such felt like the only way for me to be held responsible for what I was putting in my film,” Kim explains. By the time 3xFTM premiered at the Seoul Independent Film Festival in 2008, PINKS was about to embark on the most prolific and chaotic time in its history.

Now that documentary was a core part of its identity, PINKS took on three documentary projects practically back to back to back between 2008 and 2011. Preproduction for The Time of Our Lives (2009) and Miracle on Jongno Street (2010) happened concurrently. The former, which documents the election campaign for Choi Hyun-sook, the first out lesbian to run for public office in South Korean history, marks the directorial debut of Han Younghee and former member Hong Ji-yoo. Miracle on Jongno Street, a co-production between PINKS and one of the oldest gay rights advocacy groups in the country, Chingusai, follows the lives of four gay men who frequent Jongno’s Nakwon-dong, a popular gay enclave in Seoul. Its postproduction coincided with the preproduction of Two Doors (2011), a politically daring film that investigates the conservative Lee Myung-bak administration’s grave mishandling of the Yongsan District 4 Demolition Site fire of 2009, which took the lives of five evictees and one SWAT member.

Although creatively stimulating, this three-year period stretched PINKS thin from financial and administrative standpoints. Back then, the grants and grassroots donations were far more modest, which meant PINKS members had to take on more part-time jobs to sustain themselves, all the while producing films practically for free.

Aside from these monetary issues, there was also a growing concern about the group’s identity. Kim says, of the existential questions that weighed on the group at this time, that “[by the time we were working on Two Doors,] almost seven years had passed since our founding, yet we were still unsure what the best way was to structure ourselves—or if it was even possible for us to be an organization with a proper internal structure. We didn’t even have minutes from our meetings back then, just to give you a sense of the organizational mess I’m talking about.”

These problems were further compounded by certain structural challenges that Korean documentarians face. In South Korea, average Koreans tend to see the documentary as a medium that belongs to television, not theaters. As such, Korean independent documentaries made outside of the broadcast network have traditionally found shelter at community and campus screenings. The first feature-length documentary to receive a theatrical run in the country was Byun Young-joo’s The Murmuring (1995), a monumental work that records the lives of former “comfort women” who were forced into sexual slavery at the hands of the Japanese Imperial Army in the early 20th century. Since then, the idea of watching documentaries at the movies has become less unusual, but the commercial viability of theatrically distributed non-fiction films remains pitifully tiny.

Stills from Two Doors.

Hence, it was a huge gamble for co-directors Kim and Hong to try their hands at the traditional distribution model for Two Doors. Repurposing videos captured by alternative media outlets and police body cam footage, the documentary challenges mainstream news coverage of the 2009 Yongsan District 4 protest and holds the conservative government responsible for the tragedy.

For context, in 2006, the city government of Seoul announced its redevelopment plan for Yongsan’s District 4, and intense friction between the government and tenants ensued over the issues of compensation. Without a mutually satisfactory agreement, authorities began the demolition work by force, and the evictees, now joined by those in solidarity, occupied the roof of a building that was to be demolished and staged a sit-in protest. On January 19, 2009, the police deployed 300 officers in response, further provoking the protesters. The following day, a violent confrontation erupted between the protesters and nearly 1,500 officers, including a SWAT team. Amid the chaos of physical altercations, water cannons shooting at the building, and a cacophony of screams, a fire started inside a makeshift tower built on the roof, eventually resulting in the six deaths.

In addition to retelling the story of Yongsan from a perspective suppressed by the authorities, Two Doors brings attention to the mechanism by which the overwhelming abundance of images and information circulating in media can be harnessed to speak truth to power. Weaving together a flux of preexisting footage taken from disparate physical and ideological vantage points with original talking-head interviews from reporters, activists, and human rights lawyers, the film frequently feels like a gripping courtroom drama slash whodunit detective story.

Given the urgency of its subject matter, Kim and Hong concluded that the theatrical exhibition would give the film a chance to serve its intended political purpose. And their risk taking paid off. At a time when 10,000 admissions were considered a symbolic box office benchmark for independent films in Korea and documentaries accounted for less than 1% of the domestic market share, more than 70,000 people came out to see Two Doors.

***

Making a film like Two Doors required a considerable amount of political courage. Former President Lee Myung-bak’s ascension to power in 2008 marked the beginning of detrimental setbacks to South Korea’s young democracy, which in 1987 had supplanted the previous four decades of dictatorship. Lee and his conservative successor, Park Geun-hye, were especially punitive toward political dissidents in a way reminiscent of the pre-democratization days.

When the near-decade-long conservative rule in South Korea came to an end with Park’s impeachment in 2017, the existence of a state-administered “arts and entertainment blacklist” was unearthed. Along with Kim Ilrhan, the names of many notable figures of the industry were found on the list, including Bong Joo-ho, Lee Chang-dong, Park Chan-wook, and Byun Young-joo. The blacklisted filmmakers were ineligible to receive funding from the Korean Film Council. For example, it is now well-known that Lee’s application for Poetry (2010) scored zero, and the Council instead decided to fund a documentary that glorifies the past South Korean dictator Rhee Syng-man. In hindsight, it is clear that PINKS was also affected by this politically motivated attack on filmmakers.

In 2015, Kim applied for the Council’s funding program for The Remnants (2016), which follows the lives of five protesters at Yongsan who were subsequently imprisoned for being among the “joint principal offenders” (the film’s original Korean title) responsible for the slain cop at the Yongsan incident, but her project did not make the cut. Unaware that she was on the blacklist at the time, Kim brushed it off as another example of the Council’s lack of interest in independent films. At a 2018 press conference where a group of blacklisted independent filmmakers denounced this government policy, Kim said, “Because blacklisting weaponizes public resources, this kind of censorship is that much more ingenious and powerful.” Fortunately, Kim was able to secure independent funding from the DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, which allowed her to complete The Remnants.

Shot over the course of three years, The Remnants functions as a sequel to Two Doors, but is made in a very different style. The news of the box office success of Two Doors reached the five “joint principal offenders” while they were serving their prison sentences. Thanks to their newfound fame, prison guards at the facility treated them more humanely, making the rest of their imprisonment more bearable. Upon their release, they reached out to PINKS, and that is how the project took off. Not only does The Remnants show their side of the story, it also skillfully navigates the strained relationships among them, especially the conflict between Lee Chung-yeon, the leader figure for the Yongsan evictees, and Kim Ju-hwan, Kim Chang-su, Ji Seok-jun, and Chun Ju-seok, who joined the protest in solidarity.

While making The Remnants, the division of labor within PINKS took hold and the daily administrative operation became smoother. In 2016, PINKS welcomed two new official members, Byun Gyu-ri and Nungcool, who had previously been collaborating with the collective in their activist endeavors. At this time, Kim Ilrhan seriously wondered if the commercial and critical successes of the films would actually benefit the group. “I asked myself, would PINKS continue to exist if I quit?” she says. Aside from bolstering the work of PINKS, Byun, then the youngest member, and Nungcool joining the group also symbolized a generational transition.

The year 2016 was a transformative year for South Korea as well. Starting in late November that year, millions of Korean citizens took to the streets every Saturday to demand the immediate impeachment of then-President Park Geun-hye, who was mired in an unprecedented corruption scandal. PINKS attended the rallies to document the people’s struggle for a more just, democratic world. By March 10, 2017, Park’s impeachment was formalized, effectively putting an end to the decade of conservative rule in the country. Exactly two months later, Moon Jae-in, the leader of the Democratic Party, was inaugurated as the president.

The 15th anniversary party in 2018.

The PINKS Academy, held in 2021.

(L to R) Kwon Ohyeon, Kim Ilhran, and Han Younghee giving a talk at Jeonju IFF.

***

No one could have guessed that another flurry of sweeping changes was just around the corner. Soon after the first confirmed COVID-19 case on January 20, 2020, South Korea entered a pandemic lockdown, changing the face of the Korean film industry. As in other countries, the airborne virus made going to the movies unviable, and the lost foot traffic was directed instead to streaming platforms. Consequently, the Korean Film Council’s funding program, which is subsidized by collecting 3% of every theatrical ticket sale, took a critical hit. The Korean ecosystem of independent productions that relied on state funding ended up in shambles.

Because PINKS’s films had always been at odds with the mainstream and geared toward a loyal, ideologically aligned audience, the industry-wide setbacks were not as detrimental to them. When the Council funding became unavailable, the members again took on more part-time gigs and focused on expanding the grassroots donations to take advantage of the collective’s greatest assets: small-scale operation and resourcefulness. In fact, they hit some milestones during the pandemic.

In 2021, PINKS launched PINKS Academy, a documentary lab initiative to provide mentorship and production help for aspiring filmmakers. Through the Academy, PINKS mentored eight emerging filmmakers. The Academy experience reaffirmed their conviction that they had an important role to play in ushering in a new generation of documentarians, and they soon launched a similar program called PINKS Playground, which helped five young documentarians, all involved in the South Korean Coalition for Anti-discrimination Legislation, produce individual shorts about their struggle. These shorts were collected in an anthology film, What Bounds Us (2023), which was screened at the Seoul Human Rights Film Festival in 2022.

Around the time the Academy was launched, Byun’s second directorial feature, Coming to You (2021), won numerous awards at the Jeonju International Film Festival and DMZ. A moving portrait of Parents, Families, and Allies of LGBTAIQ+ People in Korea (PFLAG Korea), the film tenderly gazes at how queer children and their families overcome the generational divide and fight for LGBTQ rights in the country. PINKS and the members of PFLAG Korea traveled with the film to more than one hundred community and impact screenings, both domestically and internationally. To their surprise, Coming to You went on to receive a three-year licensing deal from Netflix.

“It’s a nice feeling being able to tell people ‘it’s on Netflix’ instead of asking them to gather like-minded folks and organize a community screening,” says Byun, connecting the Netflix deal to increased accessibility, thereby boosting the film’s chance of contributing to greater queer acceptance in the country. At the same time, accessibility can be a thorny question for the PINKS films that document marginalized people for whom anonymity is directly tied to their physical safety. Over the years, several streaming platforms have been interested in acquiring past works, but PINKS has declined many of the offers due to concerns about the possibilities of doxxing and other material harms.

According to Kim, movie theaters, although still public spaces, come with a certain degree of safety and insularity that streaming cannot guarantee. While the streaming model helps the collective’s documentaries reach more audiences, it forces them to be more careful about their relationship with the subjects. “Depending on the theme or the kind of people appearing in a given film, the traditional exhibition model is more desirable. This inevitably impacts a wide range of aesthetic choices I make,” Kim shares.

This issue is immediately pertinent to PINKS’s most recent film Edhi Alice. Amid the recent resurgence of transphobia in Korea, Kim has had extensive conversations with its eponymous transgender protagonists about the film’s potential unintended consequences. As the collective has grown and garnered larger critical and commercial successes, the weight of their responsibilities both as documentarians and activists has become that much heavier.

On December 3, 2024, before PINKS could fully savor the successful premiere of Edhi Alice at IDFA, now-impeached South Korean president Yoon Suk-yeol attempted a coup with a sudden martial law proclamation, which lasted for approximately six hours. On the night of the assault on the country’s democracy, millions of Koreans took to the streets to demand Yoon’s immediate impeachment—much as they did back in 2016—and so did the collective with cameras in their hands. Everything else was put on hold. “Because Korean documentaries have been incubated and nurtured by community screenings organized by activists, our political commitments are inseparable from the form,” Kim explains.

***

Edhi Alice BTS.

Monday, January 6, 2025. PINKS gathers together for another meeting. Just a couple of days earlier, the first attempt at executing the arrest warrant issued for Yoon, holed up in the official residence, was thwarted by his security team. Despite the still ongoing protests, they do their best to look toward what is ahead of them.

The conversation quickly turns into a serious discussion about sustainability against the backdrop of the South Korean democracy in existential turmoil and the threat of the past century’s state censorship returning to the peninsula. They would like to expand their grassroots donor base, which currently covers about 25% of their monthly expenses, to be less dependent on the increasingly unreliable state funding apparatus. In light of the IDFA premiere of Edhi Alice, new PR strategies are to be launched with a focus on contextualizing the collective’s history for both the younger generations in Korea and overseas audiences that may not be so familiar with their works or the history of queer and feminist struggles in the country.

Perhaps most ambitiously, PINKS hopes to mentor young documentarians who can eventually join them and replace the elder members when they retire—and the collective lives on. As one of the few remaining queer feminist groups that emerged in the early aughts, they hope to ensure that their legacy is passed on and transformed to meet the demands of the changing times: the ever-widening political divide along gender lines, the latest wave of transphobia, and the unfolding crisis of democracy. It is a chaotic time full of uncertainties, but their recent experiences collaborating with early career documentarians through the Academy and the IDFA premiere of Edhi Alice give them hope.

So much has changed over the past 20 years, and PINKS is thrilled to see what the next chapter has in store for them. The collective’s guiding principle, though, shall remain the same so long as it exists. In Kim’s words, it is “putting aesthetics into praxis.”

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Summer 2025 issue.