This year, the Toronto International Film Festival marked its milestone 50th anniversary. Half a century of screening Canadian and international films to public audiences, first as the “Festival of Festivals” from 1976, then under its current name from 1994. On this occasion to reflect on the past and look toward the future, TIFF sold t-shirts featuring the festival’s first poster to recall its humble beginnings, and merchandise with this year’s sleek branding in black and gold to remind us of its sophisticated, world-class status today. Over the summer, the organization hosted a series titled “The TIFF Story in 50 Films,” and announced that their official content market, to be launched next year, would be named TIFF: The Market.

The careful contemplation of legacy draped over the celebratory mood, every decision an indication of the festival’s long-term priorities, and what could be expected in its forthcoming editions. There was the expansion of Primetime, a program for episodic series that began in 2015, and the abbreviation of Wavelengths, a section for avant-garde, experimental, and challenging works that celebrated its 25th anniversary. Where last year’s Wavelengths selections devoted upwards of 20 hours to its four documentaries—Collective Monologue, Youth: Hard Times, Youth: Homecoming, and exergue - on documenta 14—this year’s merely included one among its eight features: With Hasan in Gaza. TIFF Docs, thankfully, remained stable in its scope and commitments, showcasing 24 documentary films that offered a range of narratives, many of which granted intimate access into the lives and communities of the filmmakers.

With the recent shuttering of Participant Media and A24’s documentary division, and the end of million-dollar streaming deals, TIFF appears unwavering in its support of the genre, a promise and a relief for documentary practitioners in Canada and beyond. Although documentaries have been historically difficult to locate across the vast number of official selections, scattering its many titles across programs, the festival is consistent in its inclusion of doc veterans alongside local filmmakers and emerging artists.

There Are No Words. Images courtesy of TIFF

Modern Whore.

While the Green Grass Grows.

After nearly three decades of examining issues of labor, migration, and policing, Min Sook Lee turns toward the personal in There Are No Words, investigating the suicide of her mother in 1982. Through interviews with relatives and friends, archival documents, and photographs, the Canadian documentarian probes the elusive circumstances that led to the life-altering event that occurred during her adolescence. Central to this inquiry is Lee’s father, a figure with an unreliable memory, a secret past as an intelligence agent, and an unwillingness to admit fault. He agrees to participate in the film with the hopes that audiences will view his abusive actions as a cautionary tale, yet resorts to pathologizing his controlling behavior, citing a psychiatric diagnosis as proof of his incurability.

Still, Lee resists placing blame or centering the film on her father, instead directing attention to her mother’s struggle and resilience as a Korean woman who was born in Japan, raised in Korea, and then immigrated to Canada. During a time when stories of intergenerational trauma have become overworked—a shorthand to signal narrative complexity—Lee’s use of filmmaking as a tool to excavate buried family secrets is refreshing in its honesty and nuance.

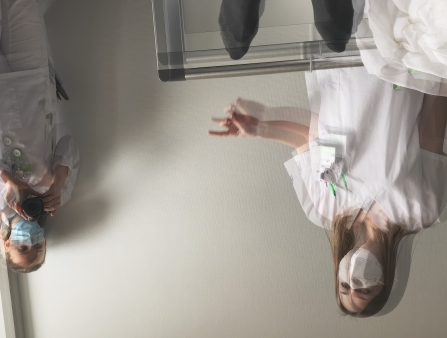

In Nicole Bazuin’s Modern Whore, based on the memoir of the same name, Andrea Werhun recounts her experience as an escort and stripper during her twenties in Toronto. Told primarily through highly stylized reenactments and animated sequences, the film draws back the curtain on sex work, detailing her clients and the financial incentives of entering the profession, as well as the accompanying challenges, such as threats of violence and feelings of shame. We learn of the differences in income between her minimum wage cafe job and escorting, and the several sexually transmitted infections she contracted, not shying away from the economics and practicalities of the trade.

A collaborative effort with Werhun as a co-writer, the adaptation is a rare depiction of sex work authored by a former sex worker and current advocate, a necessary corrective to the harmful narratives and misconceptions perpetuated by Hollywood. It should be noted that Werhun also served as a consultant on executive producer Sean Baker’s Anora, where she suggested that dancers would realistically be eating out of Tupperware in the locker room during breaks. Regrettably, the film failed to venture beyond the territory of self-representation, focusing on glossy aesthetics over any meaningful discussion—beyond brief, scattered interviews—of the importance of decriminalization and legal protections, conditions that lead individuals to enter the industry, and the experience of sex workers from marginalized backgrounds. Werhun is focused, in Modern Whore and Anora, on visibility over critique, and presence over power. What results is a neon-licked visual essay that imparts few new insights to its audience, but nevertheless charms and entertains with its glittering images.

Less concerned with sleek aesthetics was Peter Mettler, who assembled everyday digital footage from 2019 to 2021 into the slow, meandering While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts. Over the course of seven hours, the Swiss-Canadian filmmaker—who also has served as a cinematographer for directors such as Atom Egoyan, Jennifer Baichwal, Joyce Wieland, and Patricia Rozema—records observations on nature, life, death, spirituality, and renewal at the end of his mother's and father’s lives. Spanning countries and continents, Mettler and his various travel companions voyage to Switzerland, New Mexico, Manitoba, and Cuba to absorb the beauty and wisdom of forests, rivers, deserts, and mountains. Watching long stretches of these views, it’s easy to see how the landscapes offer surfaces to consider the interconnectedness of living beings, the cycling of energy, and the universal presence of water. Mettler asks his subjects this recurring question: Do you think the grass is greener on the other side?

In its attempt to contemplate grand ideas, the film unfortunately wanders aimlessly for much too long, suffering from a lack of structure and asking questions rhetorically rather than seeking to dig deeper. This most evidently materializes toward the end of the fourth part, where Mettler’s father remarks on a hike, “Peter, that’s going to be a very boring film.” He responds, “We’ll have to get you to tell stories so it’s more interesting.” A beat later: “What do you think’s more important to the earth, trees or people?” As a personal document to preserve the memory of one’s parents, the film might serve as a valuable object to Mettler, but as an artistic experiment, the diary resembles little more than heaps of home videos requiring a serious edit.

Palimpsest: The Story of a Name. Images courtesy of TIFF

Love+War.

On the other hand, Ho-Chunk and Pechanga artist Sky Hopinka’s Powwow People employs the vérité mode to great effect in his sophomore feature. Captured over three days in August 2023, the film (a 2023 IDA Pare Lorentz Documentary Fund grantee) collapses the Midsummer Traditional Powwow at Seattle’s Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center into a single day, beginning with event setup during the morning, to performances in the afternoon and evening. Indigenous children and adults across the powwow circuit in brilliant regalia made of silk, satin, buckskin leather, ribbons, and feathers compete for prizes in varying dance styles, delivering a spectacle of colors and movements that mesmerize and dazzle.

Contributing to this visual and aural delight is Hopinka’s camera, a presence that feels active and participatory, weaving through spaces and crowds to instill a sense of vitality into every shot, whether we’re watching organizers arrange chairs, staff check the sound system, or the Black Lodge Singers drum and chant. Though the performers are in the middle of the circle, the film equally spotlights Ruben Little Head, the charismatic emcee on the sidelines animating this vibrant gathering. He improvises jokes, acknowledges Hopinka, and provides entertaining commentary, lending the film another layer of immersive texture. A breathtaking artifact of tradition and community, Powwow People carries the spirit and excitement of a powwow across the screen succinctly and radiantly.

In the Centrepiece section, there was Mary Stephen’s Palimpsest: The Story of a Name, a documentary tracing the origins of the Chinese filmmaker and editor’s name. Born in British-Hong Kong, raised in Canada, having lived in France, and perhaps with paternal roots in Australia, Stephen—most known for editing the films of Eric Rohmer but also an accomplished documentary editor—embarks on an international journey through notebooks, letters and official documents to understand how she came to hold a surname that seems to perplex and intrigue in both the East and West.

Stephen discovers a long history of identity changes, confabulation, and chance counters on both her parents’ sides, with conflicting accounts and timelines that never result in firm conclusions. For instance, after finding drafts of letters to writer Ling Shuhua—who corresponded with Virginia Woolf (née Stephen) through an affair with her nephew Julian Bell—she speculates that these encounters inspired her mother to suggest “Stephen” as a new last name. However, Stephen later admits that her father was already known as Henry Stephen before Bell had ever met Ling, ruling out this too-tidy, literary-inspired possibility. Regardless of the specific motivations that prompted her parents to adopt a British name in Hong Kong, though, it’s clear that colonialism was a significant influence, whether as a survival tactic or a response to feelings of inferiority.

Of course, it wouldn’t be TIFF without flashy, highly anticipated titles such as Raoul Peck’s Orwell: 2+2=5, and Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up, which premiered earlier this year at Cannes and Venice. Before landing on streaming services, festival audiences also had the opportunity to watch the latest film of National Geographic darlings Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin. Love+War follows photojournalist Lynsey Addario as she captures the ongoing war in Ukraine and raises two children with her husband in London, a balancing act that has the Pulitzer-winner boarding trains and jetsetting between countries to complete assignments and attend school performances. Though the relationship between work and motherhood has always remained complicated, her career as a photographer in conflict zones takes the problem to extremes: when your professional life requires embedding yourself in life-or-death situations to deliver front-page images, do you continue to take risks, alter your approach, or leave entirely? What responsibilities do you have to your own ambitions and to your family?

For Addario—who has brought critical attention to life under the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2000, maternal mortality in Sierra Leone in 2009, and Russia’s targeted civilian attacks on Ukraine now—documenting injustice is not simply a job, but a calling that she’s determined to continue for as long as she can. Trailing her as she shoots, edits, travels, and cares for her children, the film presents a compelling portrait of an individual unapologetic about her duty to bear witness to history.

If this festival is any sign of what we might expect in future editions, we can still anticipate a steady stream of formally conventional works and commercial fare with a few exceptions dispersed throughout. Where other genres find themselves expanding or shrinking, TIFF believes that documentaries can reliably find audiences year after year, a resounding victory given the current media landscape.