“Tiger is coming! Close the windows!” Those were the words Mumbai and Cologne-based Bengali filmmaker-curator Madhusree Dutta remembers her elderly mother uttering while in the throes of Alzheimer’s. Initially she dismissed these ramblings. Years after her mother passed, Dutta fortuitously ran into Chinese-German media scholar You Mi in a cafe in Germany, where they hit upon a personal connection that would eventually birth Flying Tigers. This riveting, decades-spanning documentary on memory and wartime infrastructure that premiered in the Forum section of the 2026 Berlinale marks Dutta’s return to the festival after sixteen years.

Dutta places herself at the center of this personal documentary which doubles as a historiographical excavation into a forgotten World War II American military operation in Assam in the Northeastern region of India where her mother was born. Mi, whose family grew up across the Himalayas in Kumming, China, joins Dutta with Assamese writer Purav Goswami, as they research the special air force unit called the Flying Tigers and the aid they flew between both regions, to trace the way this history has affected their lives in entirely different ways.

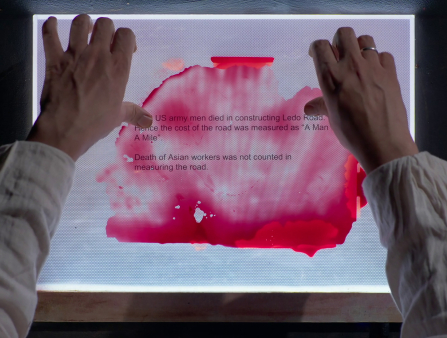

Structured loosely, the documentary unfolds sometimes like a wondrous travelogue and other times as an epistolary exchange among its collaborators. We watch Dutta and Goswami going on a road trip where they learn about the stirring poems of Assam’s once indentured Muslim Miya poets; we follow Mi as she travels to China to speak with a historian who is familiar with the regional devastation caused by the Flying Tigers project. Dutta also cross-cuts between the remnants of a disastrous U.S.-funded wartime railway connecting India, Burma, and China with contemporary footage of the “New Silk Road” railway that transports amusingly diverse goods from China to Europe, connecting past and present, the flinty memory of her mother and the hardened reality around her.

Flying Tigers traverses the lasting aftereffects of these imperialisms, moved along by the whims of diaspora, language, and the subaltern, and finally to the whimsy of personal family history, which Dutta, over a candid Zoom conversation a week before the film’s premiere, argues is public history. This interview has been edited for clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: This is your first film in two decades, since Seven Islands and a Metro, released in 2006. How does that feel?

MADHUSREE DUTTA: I was never away from cinema. I’m interested in multiple things, like archiving and image making. I did a major project in Mumbai called Project Cinema City [which was premiered at Berlinale 2010]. It was about the cities that produce image at the level of industrial production. Some cities produce cars, some coal. Mumbai produces image. It’s an imaginary city, but that city also produces imagination.

That took seven years of my life, during which I produced 11 films. There was no time for me to concentrate on directing. Then I was critically ill for a few years. Then I became interested in curating and writing, so I took a job in Germany as the artistic director of [Akademie der Künste der Welt] in Cologne. That took another four years. Suddenly, I realized, Oh my God, it’s been 20 years!

I’m happy that I took this [project]. I’m not unnerved by it. But I was petrified of technology, because that changes faster than anything else. I thought, Do I know what is available to me? That was a very tense moment. Also at this stage of one’s career, one is petrified of being pushed aside. But it’s also good. It keeps you on your toes. This amount of insecurity may not be a bad idea for artists.

D: You’ve said you started this project because of your interest in the fragility of women’s memories, and in particular, in your mother’s Alzheimer’s. In the film, you take us on a decades-spanning tour of so many incredible local histories around wartime infrastructure. As a viewer, I felt the weight of this contrast. I’m still thinking about the thousands of devocalized mules that were transported on the American Flying Tigers aircraft from Assam to China and which ended up in Korea. How did you feel the weight of this contrast between History and these more modest histories?

MD: Your answer is in your question. You brought up the 5000 devocalized mules. In the design of world history, who cares?

But that is what is affecting you, and not the dates of the Second World War—how many people died, how many cities got bombed. That’s the filmmaker’s job; to open up a far greater concern, and to tweak it so you find a parallel. I want you to be aware of how many small stories are around you every day, which is actually world history. This is my campaign against big History—or not against it, but on how to approach it.

When I was in Cologne, I started a campaign called Be a Public Historian. I invited everyone to bring one thing from their house—a rent receipt, a resident permit, a grocery list from 50 years back. And, in putting it together, we’d see whether we got a history.

This is about how everybody can be a historian. My mother died without knowing that she is part of the history of the Second World War. I am gifting it back. I’m saying, You thought you lived an insignificant life? World history actually revolved around you. That can be true of all insignificant people who live discreet lives and their roles in history. And that excites me.

This is a public history. Who will be a public historian? Everybody who has lived a life, I would say.

D: Since the film has so many modes and histories, can you talk about how the third collaborator, Purav Goswami, entered the picture, after you and You Mi met in the cafe?

MD: I was curious why my mother spoke about the tigers while growing up in Assam.

So when the cafe [meeting with You Mi] happened, which is a reenactment in the film, we thought that we should do something together. At the time, we thought maybe a book, maybe we would draw maps or make an atlas of stories or concepts. Maybe an art exhibition or a film. Very vague ideas. But we decided to explore the [Flying Tigers phenomenon] from two angles [of our family history]. She remembers it positively, and I remember it negatively. We had to meet after 80 years in a third country, which happens to be very interestingly Germany, to find this connection.

As I started thinking of the film, we realized that if I am a foreigner in China and if Mi is a foreigner in India, then I’m equally a foreigner in Assam. So a voice from Assam was required. I needed somebody else who is much more settled. That way Purav, Mi, and I would be very mainstream, settled, comfortable people. We are visiting from our zones of comfort, which is also a little bit of a place of power and privilege. The three of us had to be equal in stature vis-à-vis our own spaces.

I want to differentiate between fact and truth. Truth is a perception, and perception is very important. Facts say nothing.

—Madhusree Dutta

D: Early on in the film, you say, “I love fakes. I think they’re quite original.” That made me laugh. Later, when you’re talking to You Mi on Zoom, she casually says, maybe even sounding a tad dismissive, “You have a penchant for mixing documentary with fiction.” I found myself connecting these lines. Do you find yourself connecting them?

MD: If you see my earlier work, I’m one of the earliest practitioners of hybridity in narrative strategies. [In Flying Tigers] Mi is playing her role, I’m playing mine, and we’re friends. That’s part of the film. Before every scene we used to decide what we were going to cover. I knew that she was going to slightly blame me. But that [discussion about Chinese Jeep Girls] is one of the very few places where there’s a little slight discontent between us.

We agreed to do that because I want to differentiate between fact and truth. Truth is a perception, and perception is very important. Facts say nothing. Facts are the official history, like dates or Wikipedia. Many people talking about this film say, “You must have done so much research.” I’m not a researcher by practice or by training. The research that I have done is from sitting in my home in Berlin or Mumbai. I did not go to many archives. I had [some] research assistants, but it wasn’t anything nobody else could find. It’s all slightly obscure, but not buried history.

The thing is to connect, and that connection is fictional. Who knew that my mother had any idea that it was the Second World War that was making her see tigers? I’m making the connection. It’s such a fantastic story. This connection, you can call it fictional, but according to me, it’s a perception. It’s not a fact. I don’t have a recording of my grandmother saying, “Hey, don’t go out, don’t meet any soldier, and don’t meet any tiger.” I don’t have that record.

Fact is very limited. Truth, you will have to extract from facts. I’m not saying fiction means nonfactual, but it is extra factual.

D: Do you then distinguish between fiction and construction, or connection and construction? The whole documentary is a construction of various nonfiction methodologies. Do you see it that way?

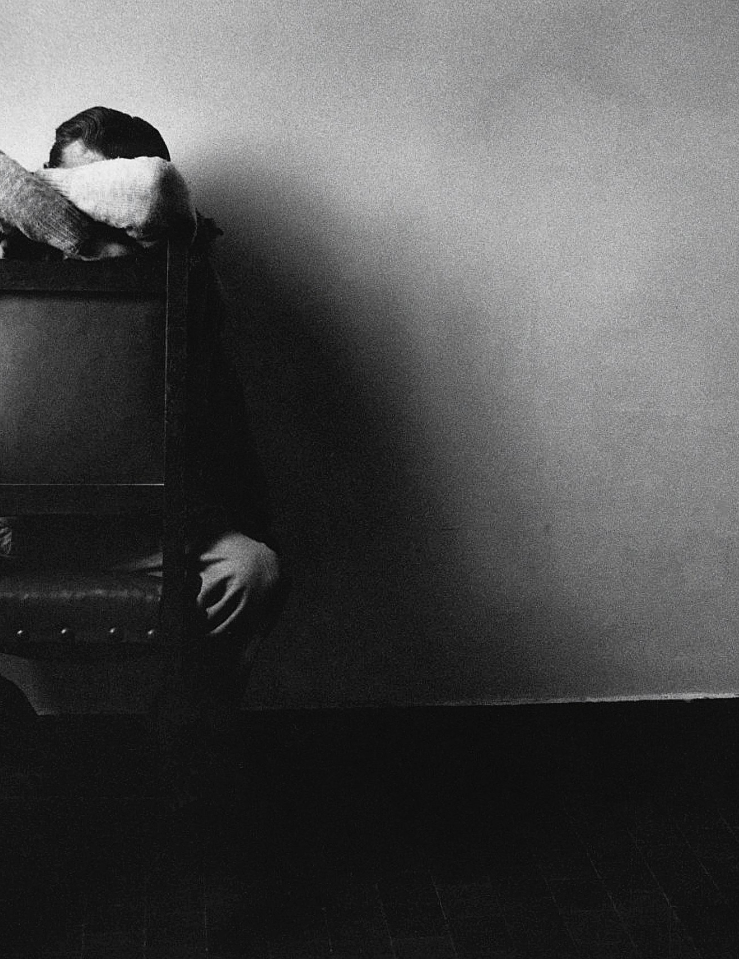

MD: Yeah, and in that construction, I also go cross-disciplinary. Sometimes I use only an art installation, like that boat at the riverbank. There are various reasons I cannot go into details [about those boats]. I need to protect my protagonist. They are vulnerable politically. That’s true of Germany, China, and India equally. I’m not isolating any particular state. That’s why there is not a single person from the Polish city Małaszewicze who appears in the film. [Nor does] a single person from Assam. I’m walking with them; they’re standing with me behind the camera, but I’m not putting them in. But I want to put their voice, I want to put their life. So then I think of other strategies, use some other discipline, like art, music, or songs, which I used without shame.

That’s construction. You can call it fictional. Or you can call it giving a body to the fact. It helps that I have been a curator, so I have access to these things. That is why I have a problem with insisting on documentary, which is tangible. The intangibility is perception, and that has to be brought in if you are practicing some kind of truth, which goes beyond dry facts.