Through works that animate the archive, cast towards various futures and play with performance, the films in the 66th Flaherty Seminar deconstruct, disrupt and question what is known, how we know, and the impulse to know or make sense of.

The Flaherty Seminar, already operating outside of convention with its film selections hidden from audiences until viewing, becomes even less transparent with this year’s chosen theme: the late Martinique writer/poet/philosopher/critic Édouard Glissant’s theory of opacity.

Opacity is of curator Janaína Oliveira’s doing and is in conversation with much of her work as a researcher, programmer and professor based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. For her, a Black woman programmer, working outside of mainstream film circuits is not a limitation; rather, it opens a well of expertise from which she drew in the process of assembling this seminar, which ran from July 9-18.

Specializing in over 10 years of work with African and Black diasporic films, Oliveira is less interested in contorting to the understandings of traditional film canons and conversations reiterated in Western thought. Instead she focuses on an entirely different approach and knowledge set, one rooted in acts of relation, rather than duties of representation alone.

Naturally, Glissant re-emerged as a framework for this work. His theory of opacity challenges many notions, including the idea that understanding could actually be reached, because of the inherent multiplicities of humanity.

But if it can’t actually be reached, why do some keep trying? The answer is always a tendency of white supremacy. Armed with opacity, Glissant refuses being understood as a prerequisite for acceptance in his role of the “other,” and he attacks the need to know. For Opacity, Oliveira selected filmmakers whose work echoes this refusal.

In this state of epistemological weightlessness, we are asked to shed bodies of knowledge and ways of knowing informed by the limits of our own understandings, realities and oppressive histories. Consequently, Oliveira has intensified the trust exercise that is the Flaherty Seminar. And what is learned here? Faith, among other ways of knowing.

Many films in the seminar press upon the faith residing in our bodies, but the Sudanese Group’s Ibrahim Shaddad’s Hunting Party eviscerates it. The experience is haunting and lasting.

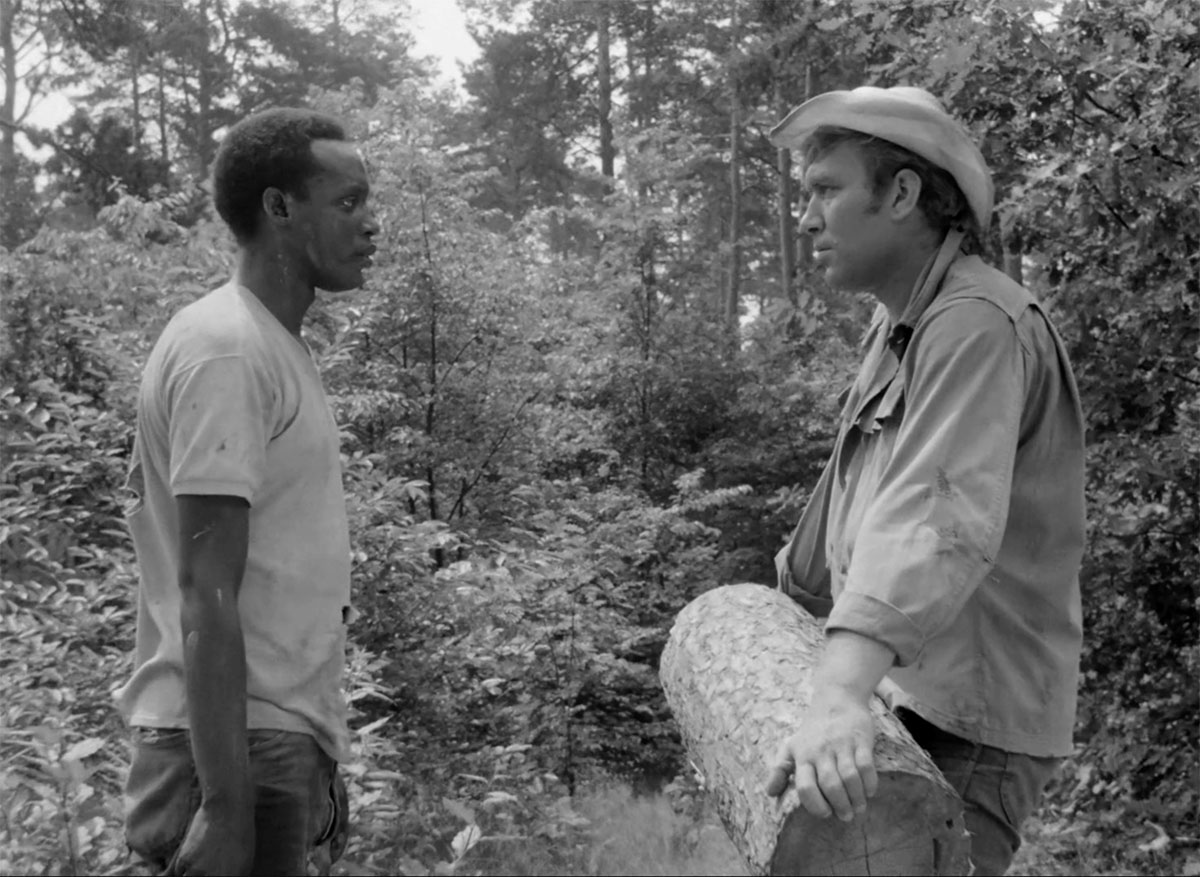

The film illustrates the painful dissonance created from conflict between societal and embodied knowledge. In it, Joe, a hungry and thirsty Black man escaping a blood-craving mob, runs into Glenn, a white hunter resting in the woods.

Eyeing the hunter’s canteen, Joe attempts to swipe it, only to be caught by the hunter. Conventional wisdom informs us that Joe has run out of luck. However, in Shadadd’s story, the opposite is true. With finessing, Joe is able to receive food and water in exchange for labor.

Initially, racism acts accordingly as Glenn flashes his assumed superiority over Joe, but their dynamic is complicated as the hunter finds himself slowly developing a mutual relationship with the escapee, and vice versa. This is heightened in a tension-filled scene where Joe takes the chopping axe and the two men meet eye to eye. Expectations of retribution and stereotypes of savagery reflect in Glenn’s face as he realizes his vulnerability in the hands of a man that Glenn’s particular worldview defines as dangerous.

However, laughter evaporates the tension and for the first time we as audiences collectively exhale suspended from fears of what we know: In the eyes of a white man, an armed Black man is a problem.

This scene, like most of the film, plays with our assumptions, whatever they may be. In this moment, the minor bond built between the two men is what brings them closer and makes the idea of harm actually laughable. The experience in the time they shared working together is what allows both to create a new source of knowledge to move through, one in which they see each other as human. Trust is formed.

It is also why it is so devastating that when Glenn is given the chance to manifest this trust after Joe decides not to run away when the mob nears, he fails.

The rising tension, between the approaching armed mob and the two men, created by quick cuts, is debilitating. It illustrates not only the impending murder but the impending decision Glenn must make.

Although it’s the 1960s and the two men are outnumbered and we know how it will end before it does, the possibility of difference is just as deafening in the moments leading to the shooting. We are as shocked as Joe, whose face fills the frame before he falls, even though we aren’t shocked at all. And we aren’t the only ones.

Paralyzed by dissonance, Glenn is stuck in time as the mob rambles on idly, as though no one has been murdered. One member makes a remark about being held in suspense, unsure if Glenn’s allegiance to the group—to whiteness—would be maintained.

Their assumed shared racial superiority is the societal knowledge Glenn is expected to act from; his shooting of Joe should come without hesitation. Yet it does.

His hesitation is him questioning his ideological and racial allegiance despite the relationship he’s built with Joe. And although he has opted for the norm, he is shaken, unable to deny what he knows is fractured, forever.

For Shadadd, the film’s director, this is the point.

In an interview at the NY African Film Fest, he states, “It was very difficult for me not to allow Glenn to take a somewhat positive stance, a stance beyond the social norm defying the foreground and his expected norms on the society.” But alas, social change is not easy. Much social impact, awareness and experience is necessary to bring and act out of the box. I hope that Glenn, who shares with Joe a moment of peaceful togetherness, a brief dream of real which he would carry forever, I hope that might affect Glenn’s attitude in the future and induce him to act otherwise.”

Here, to act otherwise is to revel in the unknown. Shadadd’s Hunting Party is an invitation towards opacity.

Now, as a Black woman, exhausted with seeing Black death in exchange for a grander message, I want to see the unknown. However, what stays with me isn’t Joe’s death; it’s Glenn’s paralysis. His face. The look of someone who has entered the abyss of opacity because they did not act otherwise and for the first time, regretted it. The unknown now is closer than it was before. I want more, and yet this is not something to overlook—not in 1964 when the film was released and unfortunately not now either.

Oliveira carefully curated an unforgettable experience, each film and conversation edging us closer and closer into that opaque abyss. Thankfully these lessons are not trapped within the seminar; she and many other underrepresented programmers are working to bring more transformative films, conversations and experiences to more audiences. We are all better for it.

Ashley Omoma is a filmmaker and writer operating under Toni Morrison’s adage, Racism is a distraction. Ashley's stories paint worlds and people, existing beyond such distractions, or at the very least, striving to.