“We’re Not Making Twins”: iNK Stories Founders Develop Documentary AI-Powered NPC Avatars

Block Party . Courtesy of iNK Stories

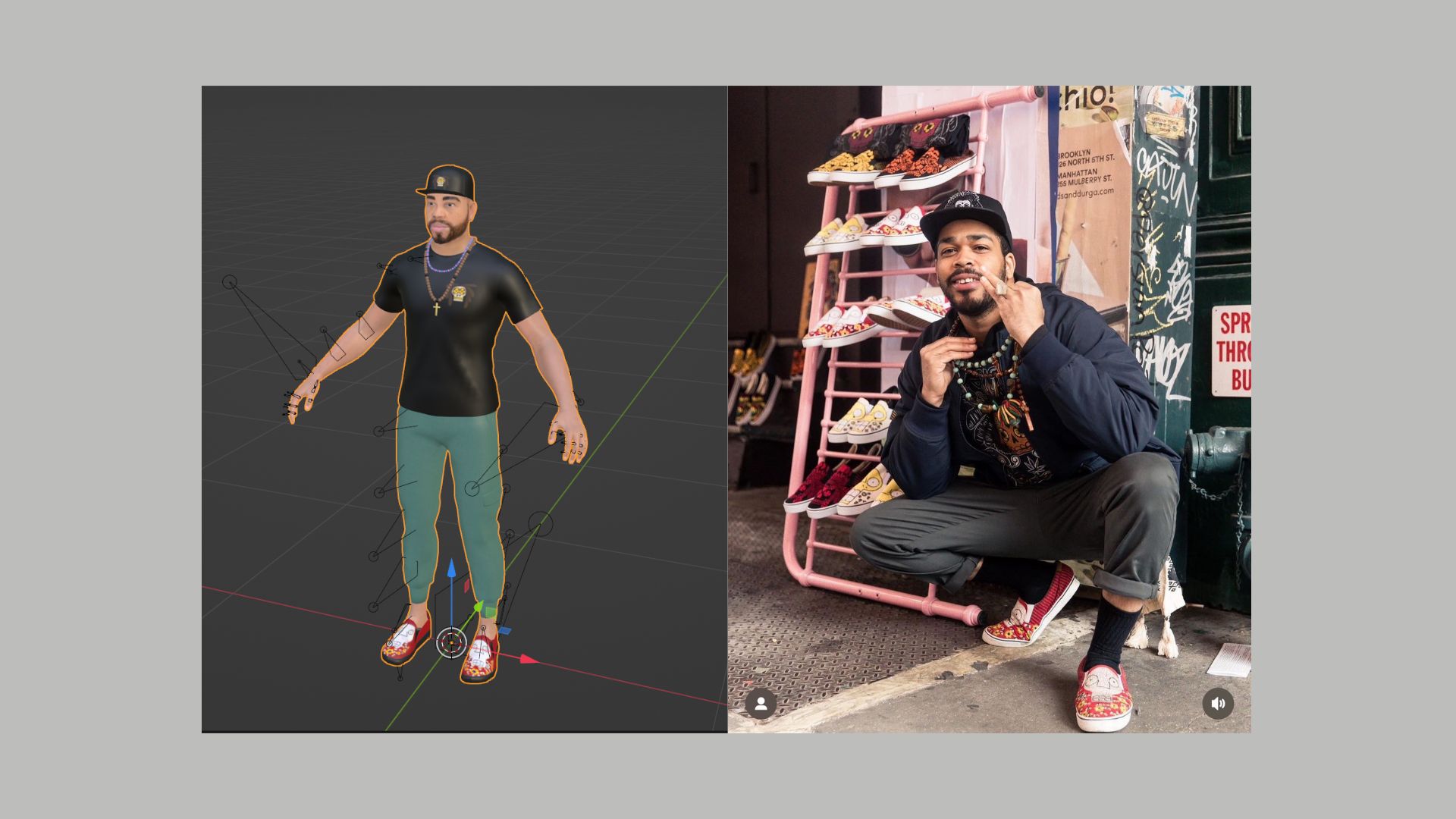

No longer bit players, Non-Player Characters (NPCs) are taking center stage as documentary subjects in a new video game. For their new work-in-progress Block Party, veteran game developers Navid and Vassiliki Khonsari of iNK Stories, are building an open world that reflects their own community of Brooklyn, NYC, populating it with AI-powered NPC avatars in the likeness of the duo’s real-life neighbors.

Across the industry, generative AI is changing the game for NPCs, as major studios such as Ubisoft and startups like Inworld AI race to build tools to create complex fictional NPCs. But iNK Stories, the studio behind the hit documentary game 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, is taking a radical approach to AI NPCs by collaborating closely with documentary subjects. They’re tapping into 3D scanning, motion capture tech, documentary interviews, along with two types of AI software, to digitally simulate documentary subjects in the game as interactive avatars. So far, they’ve imported 16 avatars into Block Party. These documentary avatars can talk, but they don’t say the words or even use the voices directly from the original recorded interviews. Instead, their words are generated in real-time through bespoke AI software, synthesizing data from the studio’s original interviews (about 3 hours’ worth each). The words are then vocalized through yet another AI tool, this time from ElevenLabs, which simulates the documentary subject’s voice and manner of speaking.

In June, I visited Ink Stories studio in Dumbo, and Navid took me on a quick tour inside Block Party on his laptop. On a digital Brooklyn sidewalk, Navid approached one of the avatars, casually sitting at a vendors’ stand, lined with sneakers. Navid opened his mic. “PJ, this is my friend Kat,” he said. I asked a question about PJ’s shoes. Then I asked again in different ways, a few times. The system is still a bit staggered and slow, but it’s working, and each time PJ gave a slightly different, nuanced answer. His voice and manner of speech are strikingly like the original recording. A week later, over Zoom, I talked again with Navid and Vassiliki about this experiment and its profound implications for the documentary field. The following interview is edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: Where did you get that first idea to bring together NPCs, AI machine learning, and documentary?

NAVID KHONSARI: Our objective has always been to be authentic in the worlds and the people that we reflect. Especially with Vassiliki’s background as a visual anthropologist. When we were starting Block Party and wanted to be authentic to Brooklyn, the non-playable character was not what we were striving for. We were looking to bring real-world characters into it.

VASSILIKI KHONSARI: We’re working within a non-linear medium, and NPCs are often very cardboard. They serve one function. And so for us, the challenge was to truly create a non-linear dynamic experience with NPCs. Dynamic characters that are just as much part of the world and a reflection of something fresh and exciting, as opposed to just serving one slice of dialogue or moving or setting up the mission in a game.

NK: AI tools have been a part of game-making and world creation for decades. Recently, we have seen a huge rise in these tools. Yet challenges exist in terms of copyright infringement and data mining. All the things that have kept people apprehensive about using it. So we started from the ground up. This is a partnership with the individuals. This isn’t a one-way road. We are embracing every element of who they are, whether it’s their personalities, whether it is their professions, whether it’s their beliefs, whether it is their background, whether it’s race…

VK: So it becomes a process of co-creation. It’s something you’re familiar with, obviously , Kat. [Laughs.]

D: I was very happy you used that word.

VK: Yes, yes. And that’s also part of our motivation. How do we shift industries, right? We’ve been trying to do that with our conscious casting all the way back with the big AAA games we’ve been doing. And now this provides a really interesting opportunity.

D: How do you explain to your documentary subjects what you would like to co-create with them?

VK: We start by explaining that together, we’re going to create an avatar. So, you’ll exist in a digital space, and this avatar will represent you, in the ways that hopefully you relate to and can represent you or can conjure some parts of you. I mean, we could never recreate another person. We’re not looking to create twins, but an ecstatic version of someone in that world. When people are classically represented in documentary films, they’re walled into the specific questions or specific responses that they’re making. They become static, tied to the responses that they gave to certain questions at a particular moment in time. And so, unlike that, we want to create this dynamic version of that.

NK: The individuals are the greatest user testers for us with the AI-generated material because after they have a conversation with themselves, they can come back to us and flag anything that just remotely isn’t in line with their way of thinking or isn’t how they would respond or is incorrect. That’s where we’ve seen the greatest amount of magic, seeing an individual talk to themselves.

VK: Rewinding a little bit, it’s really important to note that there is a really important code of ethics to follow because it’s not plug-and-play. It’s a process. And there are authorship and directorial decisions that are made in the representation of that character. It’s fine-tuning the avatar that you’re creating. But that’s also where the fear is, because in the wrong hands, it can also foster the opportunity for a lot of exploitation and misrepresentation.

D: Can you speak a little bit more on those ethical dilemmas? What keeps you awake at night?

VK: Well, it’s testing, testing, testing. What is the emotional truth? What’s the ideological truth of these characters and how they represent themselves?

NK: We need to make sure that we don’t put unnecessary guardrails that make them generic. We don’t want to neuter or homogenize.

D: Do you use a documentary consent form?

VK: It’s more of an expanded documentary release, but it’s not just in the terms, it’s more in the dialogue and relationship we have. This has been an exploration for us, so we’ve been gravitating toward people with whom we’ve developed trust. And once you scale, I think obviously it becomes more complicated, so that’s evolving.

D: Do you negotiate separate contracts for each documentary co-creator?

NK: There’s those who want to be a part of the world, like Miss Yolanda [an older Haitian school teacher] who sees the opportunity for her future generations of her family to be able to engage with her. She’s driven by that incentive. And then you’ve got somebody like PJ. He’s a designer of these killer vans with these Jamaican slash Rastafarian hand stitch, which is all done out of Mexico, and he sells them. We’re giving him a platform. So when we negotiate contracts with him, whatever comes from the interactions that allow him to sell IRL shoes, then we do that. The digital version we can have in there to represent it. In terms of compensation, we look to compensate them on every step of the way. They are our collaborators, from the interview process to their involvement in time and how players engage with them. This is also a work in progress because we haven’t really taken this out to share publicly.

VK: To add, this is a hot-button topic, with the SAG strikes over representation and licensing, life rights images, voice performance. We’re very cognizant of that. And we want to contribute in this space in a way that sets some ethical standards. We’re looking at exploring how to create a licensing agreement with the people who are storytellers in this world. There are these frontiers that need to be examined and thought about in responsible ways. We don’t perceive it as just a one-time licensing deal and then one and done. I think it’s really important to allow people dignity and the rights to their image, to their character in ways that flatties (linear documentary films) are confronting, but there isn’t that same standard.

NK: People are very much kind of concerned and rightfully so. And that’s why we made the effort to do what we’re doing, because we weren’t happy with the tools that were out there...

VK: Or the agreements that are out there and the representation that is out there, the financial structures that are out there…

NK: The compensation that’s out there…

VK: All of these models need to be examined and written with the right intentions of equity.

D: What are the broader implications for the documentary field?

VK: I think it’s one of the biggest innovations in documentary, hands down. It’s allowing for a totally different way to engage with documentary, “subjects” or documentary material, and documentary storytelling. It’s participatory, it’s interactive, it’s evolving, it’s adaptive. The potential for this type of co-creation within the digital space is really a watershed moment, and it’s our responsibility as artists coming from the creative industry to really be at the forefront and hopefully be setting terms based on equity.

iNK Stories plans for the alpha launch of Block Party next year.

Katerina Cizek is a Research Scientist and Artistic Director at the Co-Creation Studio with the MIT Open Documentary Lab.