Across his career, Polish-German filmmaker and media artist Michal Kosakowski has engaged with the dark sides of humanity. Working across documentary, fiction, and experimental film, Kosakowski demonstrates a commitment to exploring the cinematic medium and the subject of trauma, and the ways in which these two elements shape collective memory. One of his most notable works is the short Just Like the Movies (2006)—an experimental documentary that compiles movie scenes foreshadowing the 9/11 attacks, aiming to show the power of cinema to visualize apocalyptic images long before they became reality.

His new feature-length documentary Holofiction (2025) takes on a similar structural approach. For Holofiction, Kosakowski set out to investigate the iconography of Holocaust representation in fiction film and how it contributes to collective memory of the human tragedy. As a point of departure, he takes Claude Lanzmann’s famous statement: “Fiction is a transgression. It is my belief that the depiction of certain things is prohibited”—and enters into a polemic with it. Almost ten years ago, he began a project with the goal of watching every fiction film about the Holocaust he could find, cataloguing the recurring visual tropes, and ultimately assembling them into a full-length film.

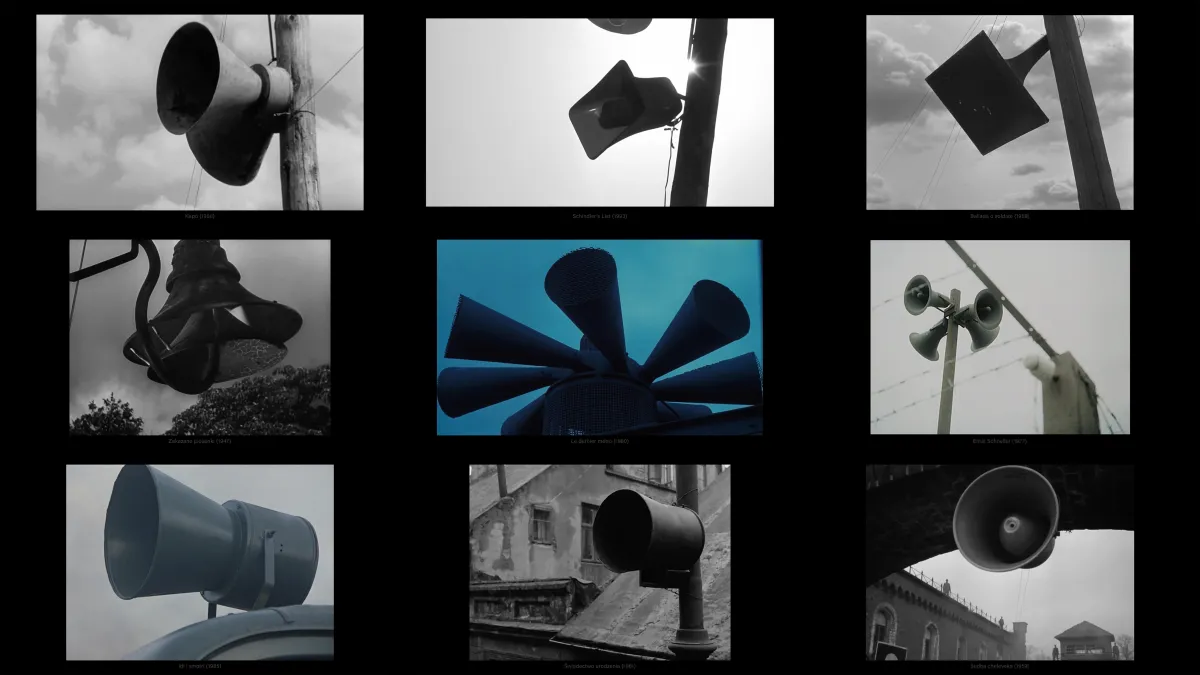

Holofiction is a 102-minute supercut that reveals patterns and motifs across decades of Holocaust cinema. This film, which has no spoken dialogue, opens with a sequence of gramophones and dances, scored by Paolo Marzocchi, linking this diverse imagery. Kosakowski assembles more than a dozen recurring tropes into chapter-like segments, each divided by a silent black screen and arranged in chronological order, charting the path from the preparations for genocide through its systematic execution. Beyond the expected scenes of pogroms and camp arrivals, Kosakowski draws out more arresting parts—the frenzied expressions of Nazi soldiers, or the eyes of those in hiding, peering through cracks at the horrors outside. In this manner, works of the Czechoslovak New Wave, the Soviet Thaw, and Hollywood blockbusters, among others, meet within a single narrative, presenting a comprehensive iconography that reveals the specific semiotics of Holocaust cinema—while also drawing parallels to the present day.

Holofiction is part of a large-scale art project, Dark Tourism, which is envisioned to comprise ten multimedia works dealing with the question of how to commemorate the memory of World War II and the Holocaust in a contemporary context. Documentary spoke with Michal Kosakowski following its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival about this larger project and the monumental work behind Holofiction. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: In the press booklet I received before the screening, I learned that Holofiction is one of the ten upcoming projects about WW2. Can you tell me where this specific interest comes from?

MICHAL KOSAKOWSKI: It started a long, long time ago. I was born in 1975 and grew up in Warsaw, and in those first ten years of my life, I was confronted with so many Holocaust images on Polish television—all the atrocities, concentration camps. They were showing a lot of films [on Holocaust themes], even in the afternoon. So it became kind of a trauma to me.

And then I became a filmmaker, and I was always into dark topics. At some point, I became drawn to the dark tourism subject. This term was invented at the beginning of the 90s in the UK by two English professors, as a way to describe tourism to places of destruction and atrocities. This fascination is similar to, for instance, when you see an accident on the highway and you stop because you want to watch, and that’s where the dark tourism starts. But then you have Holocaust tourism to concentration camps, you want to experience not only how it happened, but how things were possible. So I was really fascinated by this term, and later I came up with an idea to find new ways to commemorate WWII. Because I was really shocked to find out that so many young people don’t know much about WWII. They sometimes don’t know what the Holocaust is.

I started to make a mind-mapped project, and I came up with an idea to make 10 interdisciplinary projects that deal with new ways of commemorating. In a way, I extended Dark Tourism towards the discovery of the images and how to deal with the images that are already out there. I started with Chronofiction, Holofiction, and Solofiction. Chronofiction is a big library of all existing Holocaust and WWII films. It’s more than 3,000 movies, and I investigate each day the films depict. Although they are fictional, a lot of them are based on real stories. Basically, it would be a system where you can, for instance, type “Assassination of Heydrich,” and then a portal pops out listing all the movies that depict this day with the particular event—and also situations where a family was transported from Lodz to a concentration camp.

D: I was thinking of how to properly define the Holofiction, and I would classify it as a documentary about the structural similarities of how the Holocaust is depicted in film history, am I right?

MK: Yes, exactly! In Holofiction, I try to investigate how our memory [about the Holocaust] is shaped and where this memory comes from. That was fascinating for me. I was especially intrigued by Claude Lanzmann’s saying on Schindler’s List (1993) and what he meant by the prohibition of certain depictions. Who is he to claim to prohibit something? Let’s prove the opposite. I came up with the idea of watching all those films to find the most iconographic images that define the Holocaust.

D: I am very interested in how you found where to begin with a large-scale work?

MK: It was not easy to start, because if you have one movie, what do you even take from it, how to define what to look for? So I started with twenty movies in the beginning—the most famous ones—and tried to identify the repetitive images between them. From these twenty films, I already found the core structure of the movie, because we have trains; people being arrested; scared expressions, crying, and so on. Out of these scenes, I created a concept and from that continued eight years of research, watching about 2,000 movies, and simply making notes with time codes.

D: How were you categorizing them in the process?

MK: I outlined the concept on a big poster, with the film’s structure and the scenes I was specifically looking for. You take one movie, extract what you need, and then suddenly, you also find it in films like Blues Brothers or even dystopian futuristic films—they still have similar iconography. As you saw in the film, it was possible to montage a smooth camera pan from one film to another. Over a hundred years of cinema history, WWII is the most depicted event ever. If I were to do a movie on the Vietnam War, I would not be able to, because there are simply not enough films on it. Or even WWI, too.

And above all, I see this is a document on film history itself. That's why I was so upset that they turned the lights on once the credits started rolling during the press screening—because you find that almost every important director in cinema history made a WWII film.

D: Another amazing layer in the film is that you montaged actors like Christoph Waltz, Willem Dafoe, and many other actors, who have played Holocaust victims and Nazi officers in different films, having metadialogues with themselves. How did you come up with this layer?

MK: This is an amazing thing for me because I didn’t know if it’s gonna work, but finally I found enough material. There are about fifteen actors in total playing both sides. Most importantly, it illustrates the question of who is the victim and who is the perpetrator, which is so relevant today. People are changing sides, and there is “Holocaust bashing” going on, and people are changing history. So it was crucial for me to define what our position is toward the Holocaust today.

Also, adding this layer with actors never lets the viewer forget that they are watching cinema. Because you can easily lose yourself, thinking this is real, but the actors remind you that this is actually cinema, because this content is strong and can take you way beyond.

On that note, I decided not to include sexuality in this film. I had parts in the mock-up, but it just completely broke the whole structure. It became so intense that you forgot about everything. The same goes for the depiction of physical violence.

D: Is that also the reason you are limiting yourself with gas cameras, showing them only from outside?

MK: To be honest, there are just one or two images from inside [a gas chamber], in films, people are mostly depicted going inside. There is one in Uwe Bowl’s Auschwitz (2011), but it was ridiculous and it was not repetitive for me, and did not fit the concept I envisioned.

D: And it was somewhat unexpected that you wrapped this film shortly after that scene, because I was already subconsciously envisioning how the film was gonna end according to the historical chronology, with the camp's liberation, let’s say.

MK: I wanted to do the film about iconographic shots and not recreate the entire chronology. For example, the part that I really like is the registration one, which starts with typing and ends up with archiving, stealing, tattooing, and putting up posters about Jews—because it’s all the same. There are many Holocaust films, but few depict the connections that led to the horrors experienced.

I think it's essential to emphasize that the Holocaust started with registration, and we could find the pretext and take things away from it. The overarching theme for me is how to decode fascist systems in today’s society, and we need to understand how this system works and be aware of it. And I hope this film will contribute to a better understanding.

I can give you an interesting example. During the test screenings, I had a few Turkish lawyers. And after the film, they said that they didn’t think about the Holocaust at all, but the Armenian Genocide. So they were really thrown back to their own history. And when I watch the film now, especially the part with the hangar, with the music of Johann Strauss, I am thinking about Gaza.

D: I can’t not ask: after watching all the fictional Holocaust films, what is your favorite?

MK: I think the most interesting is The Last Stage (1948). It is the first film about the Holocaust done by Polish female director Wanda Jakubowska. It is an incredible film because this woman was imprisoned in Auschwitz, and when the camp was liberated, she decided to make a film, including extras in the camp who are survivors from Auschwitz too.

I read in some interviews that the director said that we don’t have many images from the camps, but since she was there, she could depict it from her memory in her film. Her film was also very important for Janusz Kaminski, the DOP of Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. This film was a really big inspiration for the black and white film. Very beautiful film, in the sense of filmmaking, of course.

Courtesy of Kosakowski Films